The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant Matrice Young

Special Collections & Archives recently acquired two artists books from Monica Ong, a second generation Chinese-Filipino American woman born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. Her family history, like many Americans, is a complex one. During World War II, her grandparents left Fujian, China and immigrated to Manila in the Philippines. There, both of her parents were born and raised. Her father, a medical resident, moved to the US in the early 1970s with his family to settle down.

Ong studied studio art as an undergraduate at New York University and earned her MFA in digital media from the Rhode Island School of Design. She currently works as the user-experience designer at the Yale Digital Humanities Lab at the Yale University Library in Connecticut. Ong was also a literary fellow with the organization Kundiman: which seeks to create a mentorship and community space for Asian Americans exploring their creative craft, artistic freedom, and the challenges within the Asian-American diaspora. When it comes to her influences, some of them include Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Claudia Rankine and Barbara Kruger, Daisaku Ikeda, her family, and learning and connecting more with her own cultural history and heritage. Monica Ong is also a Bodhisattva, and Buddhism has influenced her work and her personhood, which you can learn more about from her interview on the podcast Buddhability, “Episode #30: How to overcome resistance in creative work.”

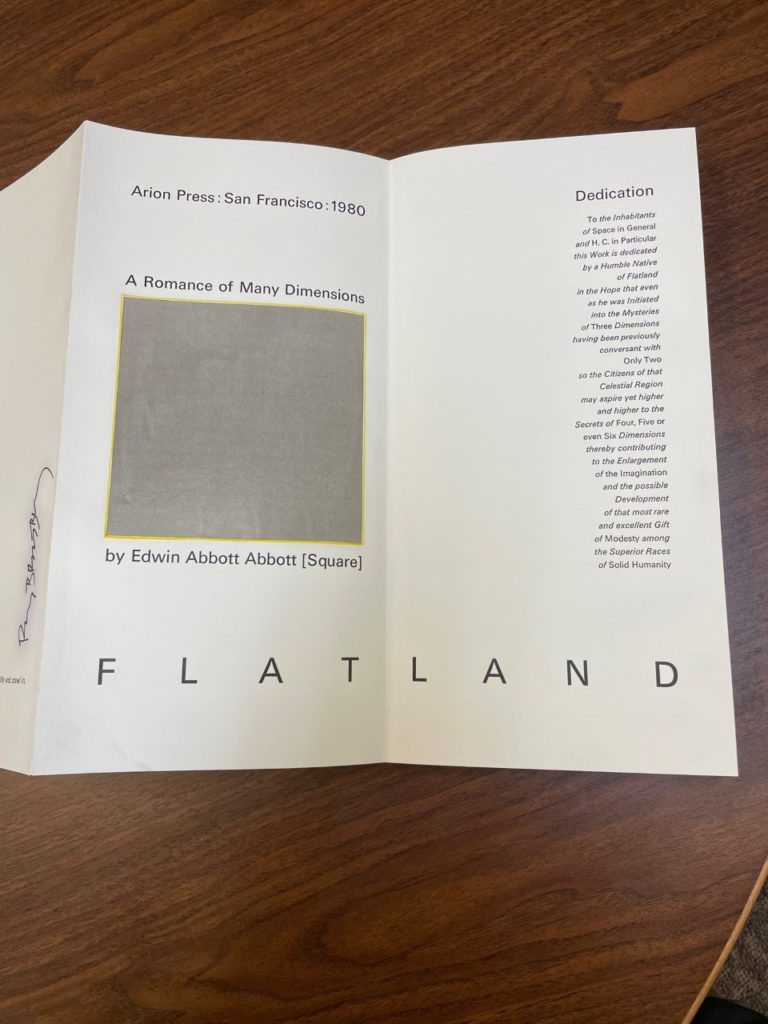

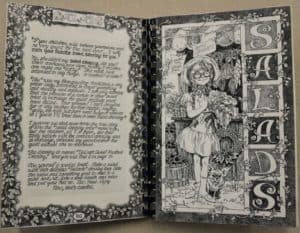

Her first book, Silent Anomalies, is a combination of her visual art and poetry that touches on many subjects of her life and family history. The poems speak on Chinese and Filipino history, politics, and identity from her perspective and understanding. She also speaks on social norms, cultural silence, and the “medical-emotional family diaspora” of her family which extends from China to the Philippines to the United States.

Ong spoke in an interview on Off the Shelf with Yvonne Wolfe about how ashamed her grandpa was at having 5 daughters, as in their culture, having sons was considered a true blessing. As a result, her grandfather dressed her mother as a boy for family portraits for several years, and Ong saw how that made her think about the cultural narratives of women’s bodies, the shame and negative values placed upon them.

She then spoke about her maternal aunt who struggled with mental illness, and how her dad, trained in Western medicine, attempted to help her but was at odds with Ong’s grandmother who was superstitious and said her daughter was possessed as a way of saving face in a world that did not understand, and still struggles with, mental illness. As such, Ong’s aunt remained undiagnosed and untreated for most of her life. Ong’s mother and aunt’s experiences were two crucial moments in her development of what she wanted to accomplish in Silent Anomalies. She wanted to think of art as a safe space to create and entertain dialogue about health issues, particularly where health and culture intersect.

Ong’s latest work, the exhibition Planetaria, is full of visual poetry inspired by astronomy, where text is integral to her artistic creation. The works in her exhibition has many different forms: shadow boxes, slideshow reels, and book carts are a few. Her pieces combine different representations of cosmological forms and celestial bodies, examples being tarot cards and Chinese astronomy.

Ong’s interest stemmed from wanting to know more about astronomy and Chinese cosmology. In an article for the New Haven Independent, she mentions how she was only semi-familiar with the Chinese system of constellations as a child. “Every fall we would have a moon festival and my family would get together, play games, and have a feast, and then there would be the story about a woman who drank a potion for everlasting life, and she went to the moon, but her lover stayed on Earth.”

When she became an adult and a parent, she wanted to pass her cultural heritage down to her son, so she began learning more about Chinese cosmology. She learned that some of the constellations in Greek cosmology appear in Chinese cosmology, as do some of the same star forms, but they are interpreted differently. For example, the stars that make Orion’s belt are three Gods of fortune in China. “There’s a lot less emphasis on mythical gods,” Ong said. “It’s a lot more a reflection of the hierarchy of society. So there are asterisms for accountants and archivists, as well as the king’s chariot drivers, and empty wells and fields. It’s a geography of the way the Emperor saw life (New Haven Independent).”

As Ong learned more about Chinese cosmology, she saw how it, like the Greek system, is “centered around male power.” She sought to change that in her work by using a feminist and personal narrative. She does this by using womanhood, the body, female scientists, and female cosmonauts. Her exhibition pieces also include her family’s ancestral history and immigration stories. Ong states that “What’s empowering about being an artist is that you can say, ‘how can we flip the script and write from a different point of view that centers the reader? How can we rethink our stories in a way that’s more inclusive for everyone?’ The palace is not up there; it’s actually your own life.”

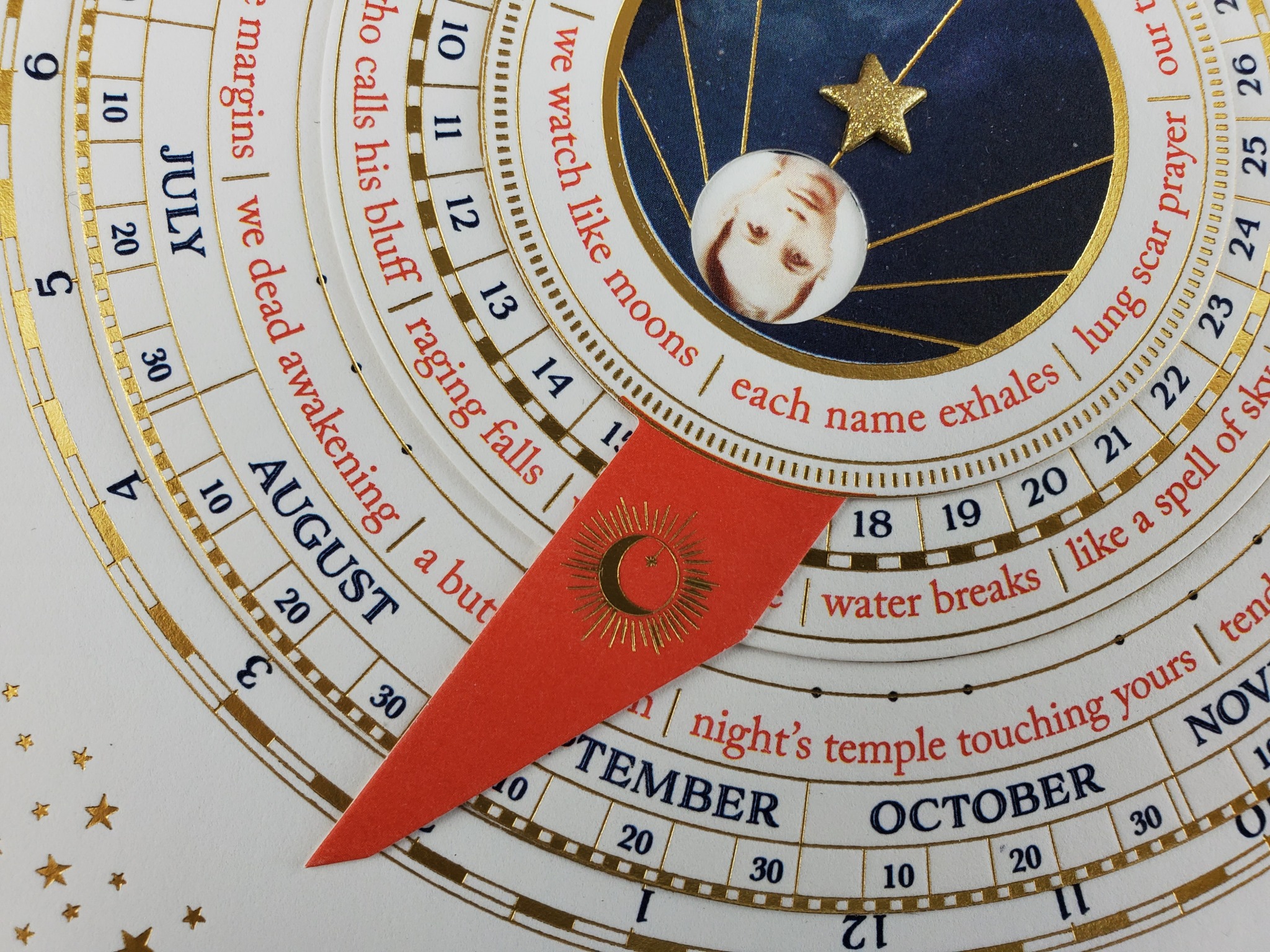

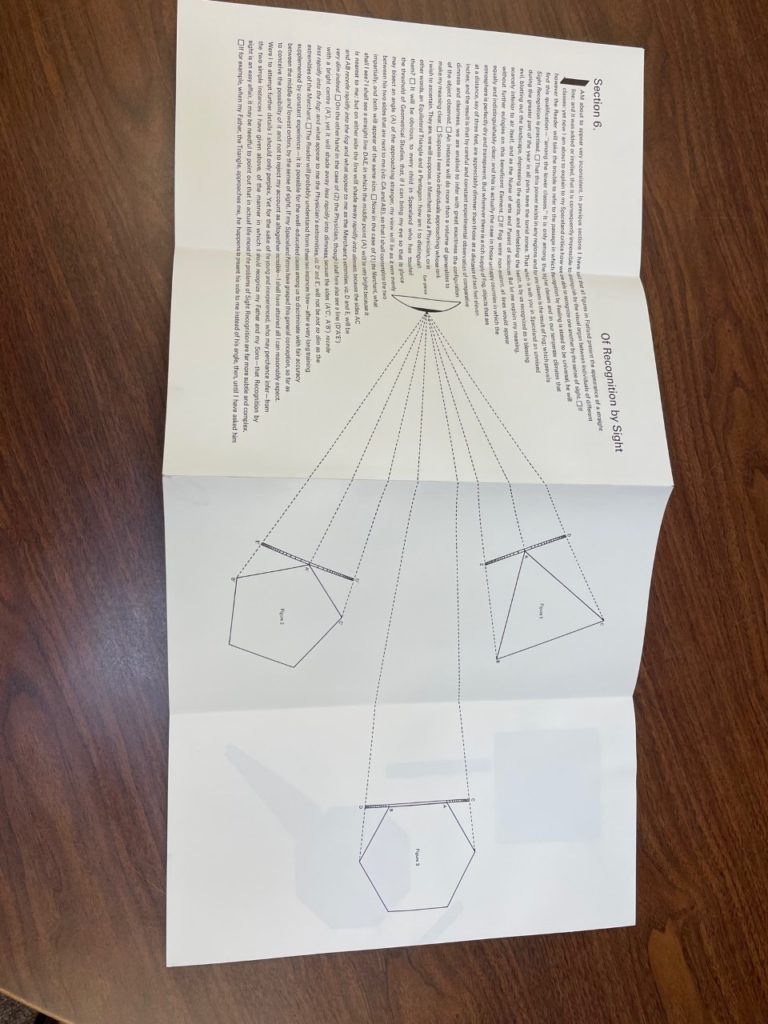

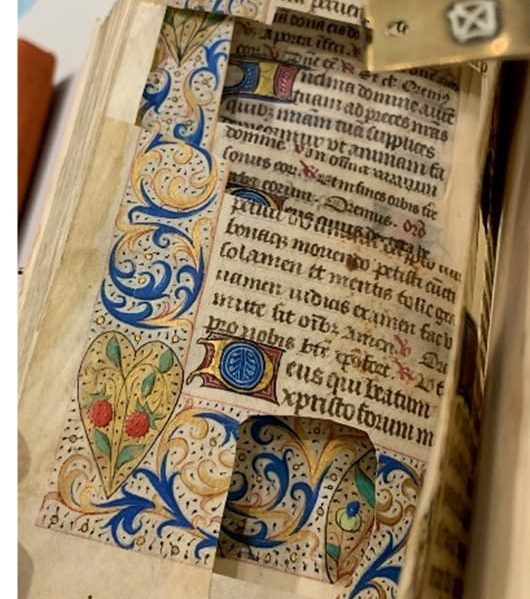

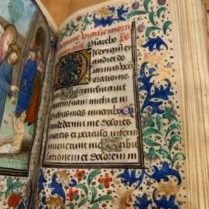

This flipped script can especially be seen in the pieces here at Special Collections & Archives. The Star Gazer: Planisphere Poetry depicts the Chinese night sky from the northern hemisphere. It is based on the Soochow Astronomical Chart of 1193. This star chart holds small phrases of beautiful prose weaved around constellational lines to form the poetry within this piece. Taken directly from her Proxima Vera site, there are a few steps to read this structured poem:

“To view the stars, turn the disc to align the desired date with the hour of night. Face south and hold the planisphere overhead with the corner marked North facing north. The map will reveal a celestial poem that awaits you among the asterisms. Let the eyes wander and read aloud to someone dear.”

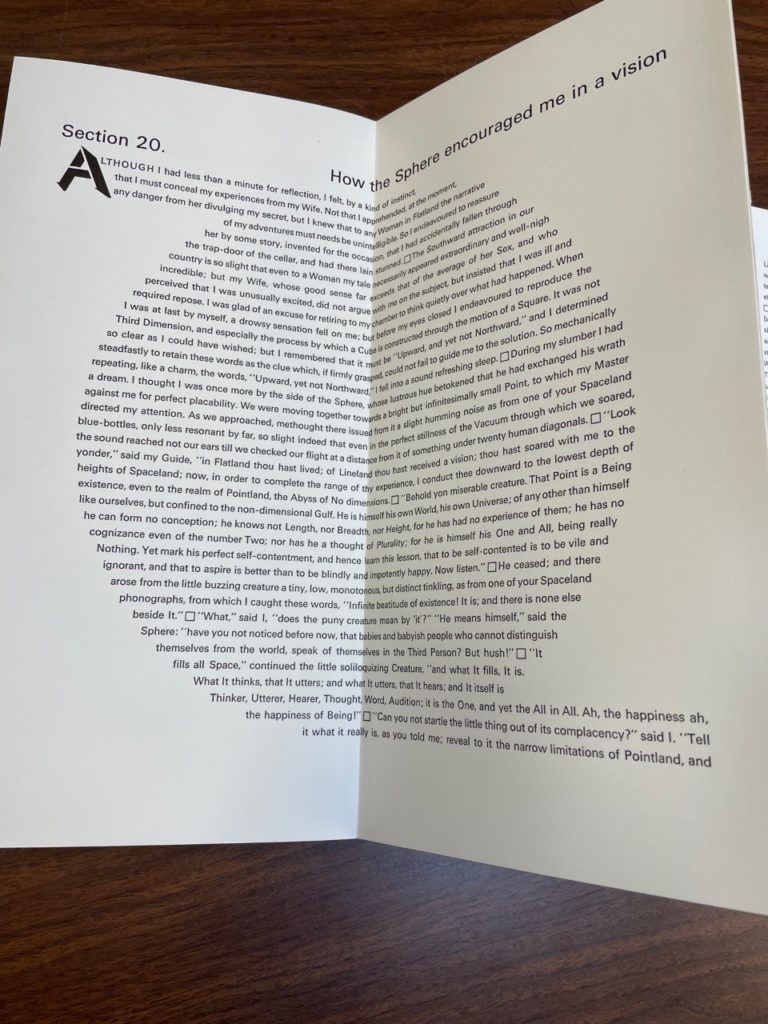

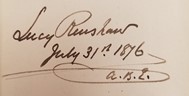

Her other work in our collection, Lunar Volvelle, also demonstrates how science, family, and poetry can weave together. Based on a device from the medieval era, Ong’s volvelle includes fragments of poetry along with an image of her paternal grandmother, whose image waxes and wanes with the phases of the moon. Ong explains her design on Proxima Vera stating, “During the full moon, my father’s mother will watch over you.”*

Overall, Ong’s work has been an exploration, a dive into family and research, connections and experiences, and solving the mysteries of what she wishes to learn more about.

Monica Ong is a visual poet, an artist, a mother, a sister, a daughter. She’s a driven Asian American woman who speaks her story, her family’s story, the story of women, particularly Asian American women, the story of immigrants and their families, cultural politics and traditions, and what it means to bean Asian American woman living in today’s society. You can check out her works at the Special Collections & Archives, and her book Silent Anomalies from our Main Library! Happy Explorations, everyone.

*Correction on description of Lunar Volvelle made 1/13/2022. Original content said piece contained multiple images of family members. Imagery in piece does not include multiple faces as described before, but one, Ong’s paternal grandmother.

Sources

Aidasani, S. (2018, November 24). Monica Ong: Capturing poetry’s healing power – positively Filipino: Online magazine for Filipinos in the Diaspora. Positively Filipino | Online Magazine for Filipinos in the Diaspora. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from http://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/monica-ong-capturing-poetrys-healing-power

Bigelow, K. (2021, April 15). 2021 cover artist: Monica Ong. Dogwood. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://dogwoodliterary.com/2021/04/15/2021-cover-artist-monica-ong/

Institute Library Press Release (2021). The Gallery Upstairs at the Institute Library presents: Monica Ong: Planetaria. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://institutelibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/planetaria-PR-final.pdf

Posted on July 2, 2021. (2021, November 9). Episode #30: How to overcome resistance in creative work. buddhability. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://buddhability.org/podcast/monicaong/%C2%A0%C2%A0

Slattery, B. (2021, June 15). Art exhibit traces a path to the stars. New Haven Independent. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://www.newhavenindependent.org/index.php/archives/entry/planetaria/

Yau, J. (2021, August 6). A poet-artist looks to the stars. Hyperallergic. Retrieved December 16, 2021, from https://hyperallergic.com/667278/monica-ong-poet-artist-looks-to-the-stars/%C2%A0