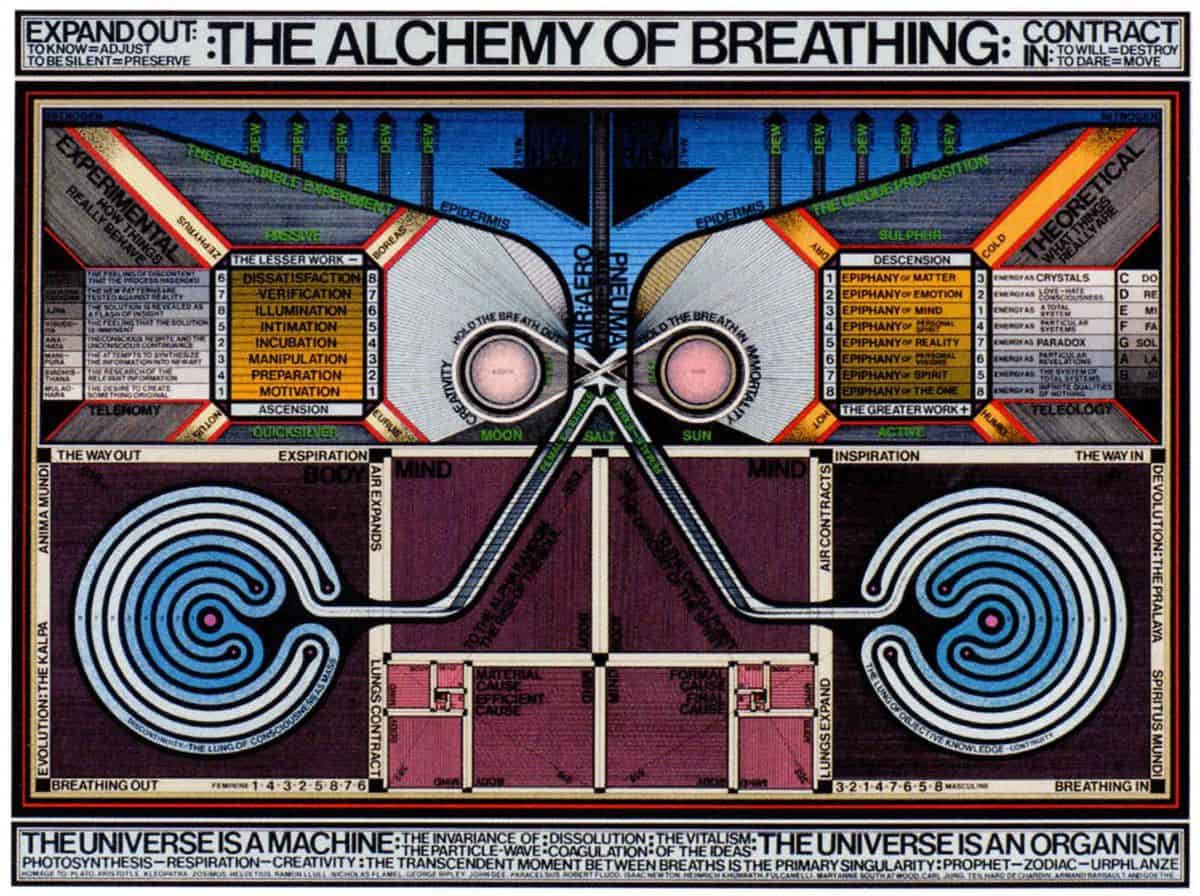

The following was written by Rich Dana, Sackner Archive Project Coordinator Marvin and Ruth Sackner were the world’s foremost collectors of “visual poetry,” artwork that combines visual elements and text. Dr. Sackner was also an internationally respected pulmonologist and inventor of many medical devices. In 1992, the Sackners created a unique exhibition of work byContinue reading “Beauty in Breathing: An Exhibit”

Tag Archives: Rich Dana

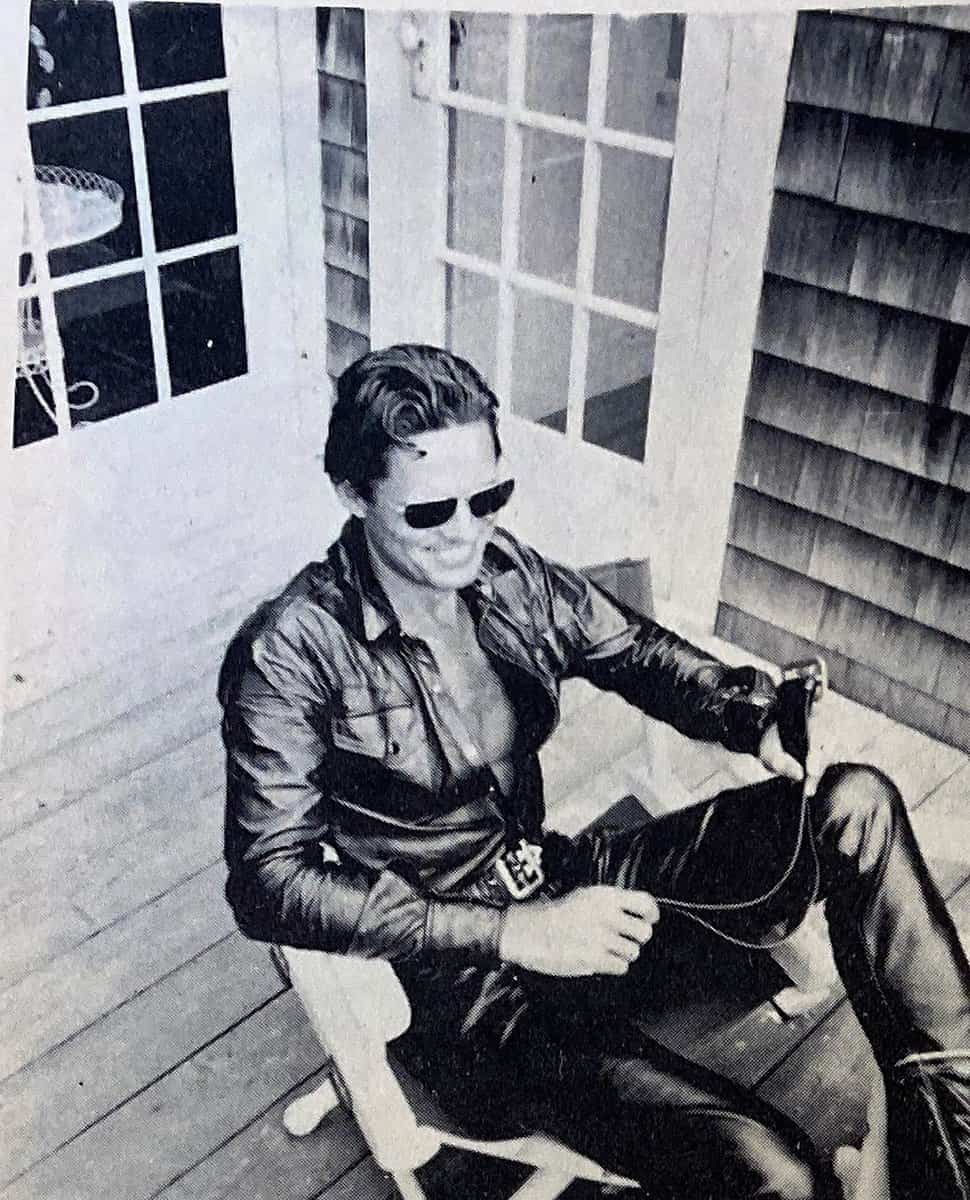

In Memory of Kirby Congdon, an Unsung Hero of American Poetry

The following is written by Rich Dana, Sackner Archive Project Coordinator Librarian On June 3, 98-year-old Kirby Congdon passed away in Key West, Florida, a town that had recognized him as its first poet laureate. Although the arts community of Key West understood the importance of Congdon and his work, much of the rest ofContinue reading “In Memory of Kirby Congdon, an Unsung Hero of American Poetry”

Welcome Rich Dana

We are pleased to announce Rich Dana as Special Collections and Archives’ Sackner Archive Project coordinator librarian. Rich Dana earned his MFA from the University of Iowa Center for the Book in 2021 and his MA from the School of Library and Information Science in 2020. He has worked as an art mover, art fabricator andContinue reading “Welcome Rich Dana”

Spirit Duplicators: Early 20th Century Copier Art, Fanzines, and the Mimeograph Revolution

The following was written by Olson Graduate Assistant Rich Dana, and curator of the Spirit Duplicators exhibit in Special Collections & Archives reading room During my three and a half years at Special Collections, I have worked with an amazing range of materials, but my major projects have focused on first, the James L. “Rusty”Continue reading “Spirit Duplicators: Early 20th Century Copier Art, Fanzines, and the Mimeograph Revolution”

Discovering the hectographic world of Mae Strelkov

The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant, Rich Dana In the 1970s, a remarkable woman from Argentina was an underground art sensation. While researching the forgotten art of hectographic printing, I discovered the work of Mae Strelkov, a little-known visionary artist from Argentina. This discovery was the sort of experience that illustrates precisely why thoseContinue reading “Discovering the hectographic world of Mae Strelkov”

Shut Your Mouth and Save Your Life: 1870 health book resonates in the era of protective masks

The following blog comes from Olson Graduate Assistant Rich Dana, who interviewed Marvin Sackner on his collection of concrete and visual poetry. Among the over 75,000 items in the newly-acquired Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry, there are many unique and one-of-a-kind art objects and artists’ books. Along with original artwork, there is anContinue reading “Shut Your Mouth and Save Your Life: 1870 health book resonates in the era of protective masks”

In the shadow of Covid-19, The Sackner Collection shines a light on “The Beauty in Breathing”

The following blog comes from Olson Graduate Assistant Rich Dana who interviewed Marvin Sackner on his exhibit “The Beauty in Breathing.” An exhibition of works from the newly acquired Ruth and Marvin Sackner Collection of Visual and Concrete Poetry at the Main Library Gallery is one of the countless art events that have been postponedContinue reading “In the shadow of Covid-19, The Sackner Collection shines a light on “The Beauty in Breathing””

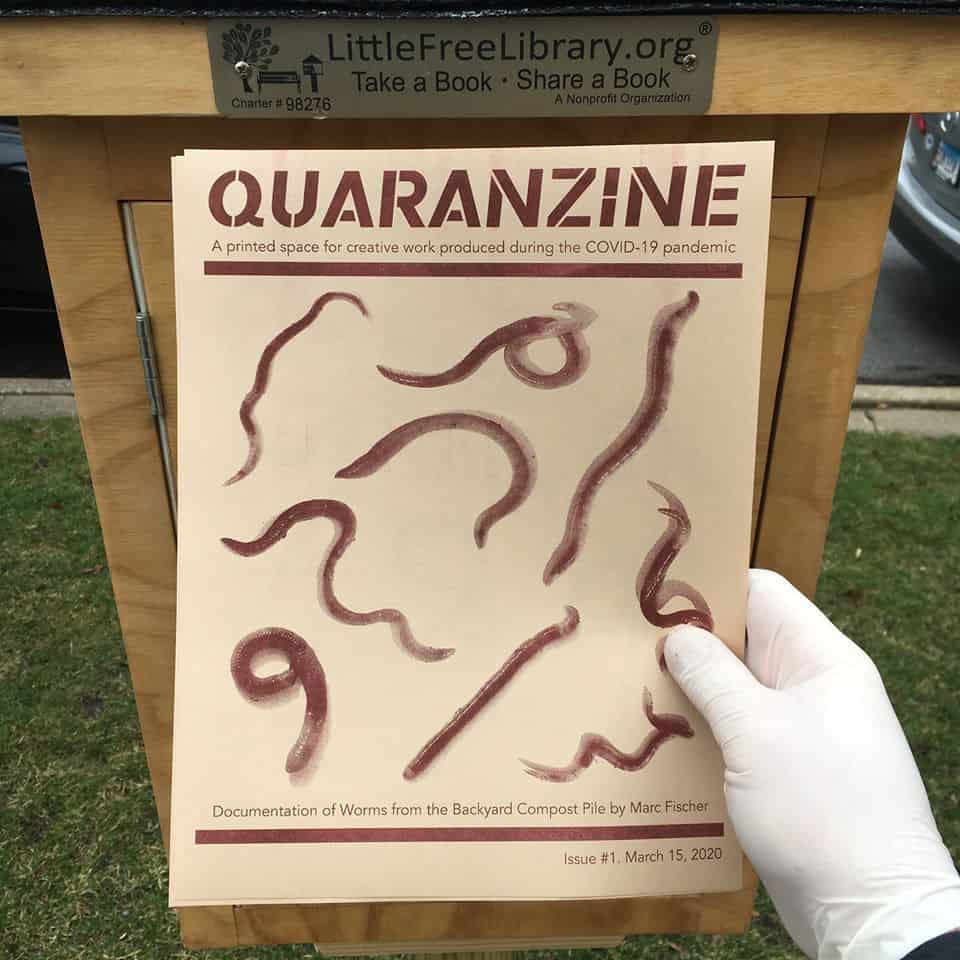

2020: The Year of the QuaranZINE

The following is written by Rich Dana, Olson Graduate Research Assistant for Special Collections. As librarians, we are engaged in service to our communities, and that service doesn’t end when the library has to lock its doors to protect its patrons and workers. All of us are faced now with leveraging any tools at ourContinue reading “2020: The Year of the QuaranZINE”

The Remarkable John Giorno

The following comes from Olson Graduate Assistant Rich Dana John Giorno, poet, artist, and activist, passed away Friday, October 12th at the age of 82. Although readers may not be familiar with his name, Giorno was one of the most influential American artists of the post-war 20th century. He blurred the boundaries between written, visualContinue reading “The Remarkable John Giorno”