“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Kelli Brommel from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “Reading Culture History & Research in Media” (SLIS:5600:0001). Mass Market Ads of a Bygone Era By Kelli Brommel Amongst the wideContinue reading “Mass Market Ads of a Bygone Era”

Category Archives: Science Fiction and Popular Culture

Spirit Duplicators: Early 20th Century Copier Art, Fanzines, and the Mimeograph Revolution

The following was written by Olson Graduate Assistant Rich Dana, and curator of the Spirit Duplicators exhibit in Special Collections & Archives reading room During my three and a half years at Special Collections, I have worked with an amazing range of materials, but my major projects have focused on first, the James L. “Rusty”Continue reading “Spirit Duplicators: Early 20th Century Copier Art, Fanzines, and the Mimeograph Revolution”

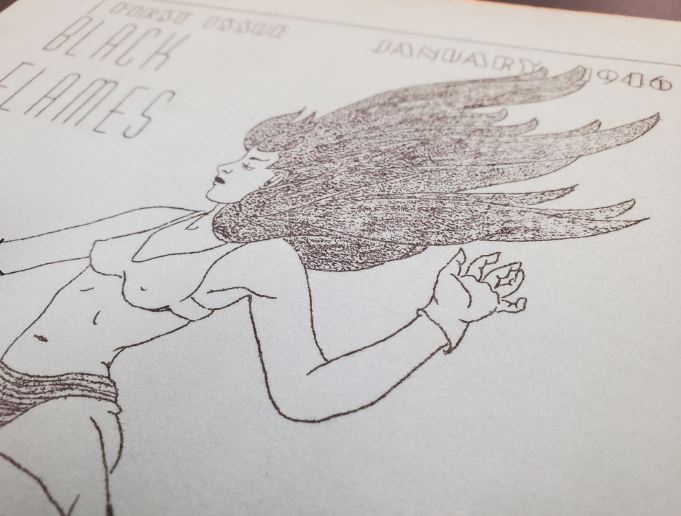

Science Fiction’s Forgotten Femfanzines

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Michael Willis from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0001) Science Fiction’s Forgotten Femfanzines By Michael Willis Black Flames emerged from the recesses of theContinue reading “Science Fiction’s Forgotten Femfanzines”

Discovering the hectographic world of Mae Strelkov

The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant, Rich Dana In the 1970s, a remarkable woman from Argentina was an underground art sensation. While researching the forgotten art of hectographic printing, I discovered the work of Mae Strelkov, a little-known visionary artist from Argentina. This discovery was the sort of experience that illustrates precisely why thoseContinue reading “Discovering the hectographic world of Mae Strelkov”

A Virtual Bibliophiles

Today is April 8th, 2020, the day we were supposed to gather for the last Iowa Bibliophiles of the academic year. The plan: come together, eat some tasty snacks, and explore some of the highlights from our collection with the help of our wonderful student workers. Our students had selected manuscripts, books, and more, researchedContinue reading “A Virtual Bibliophiles”

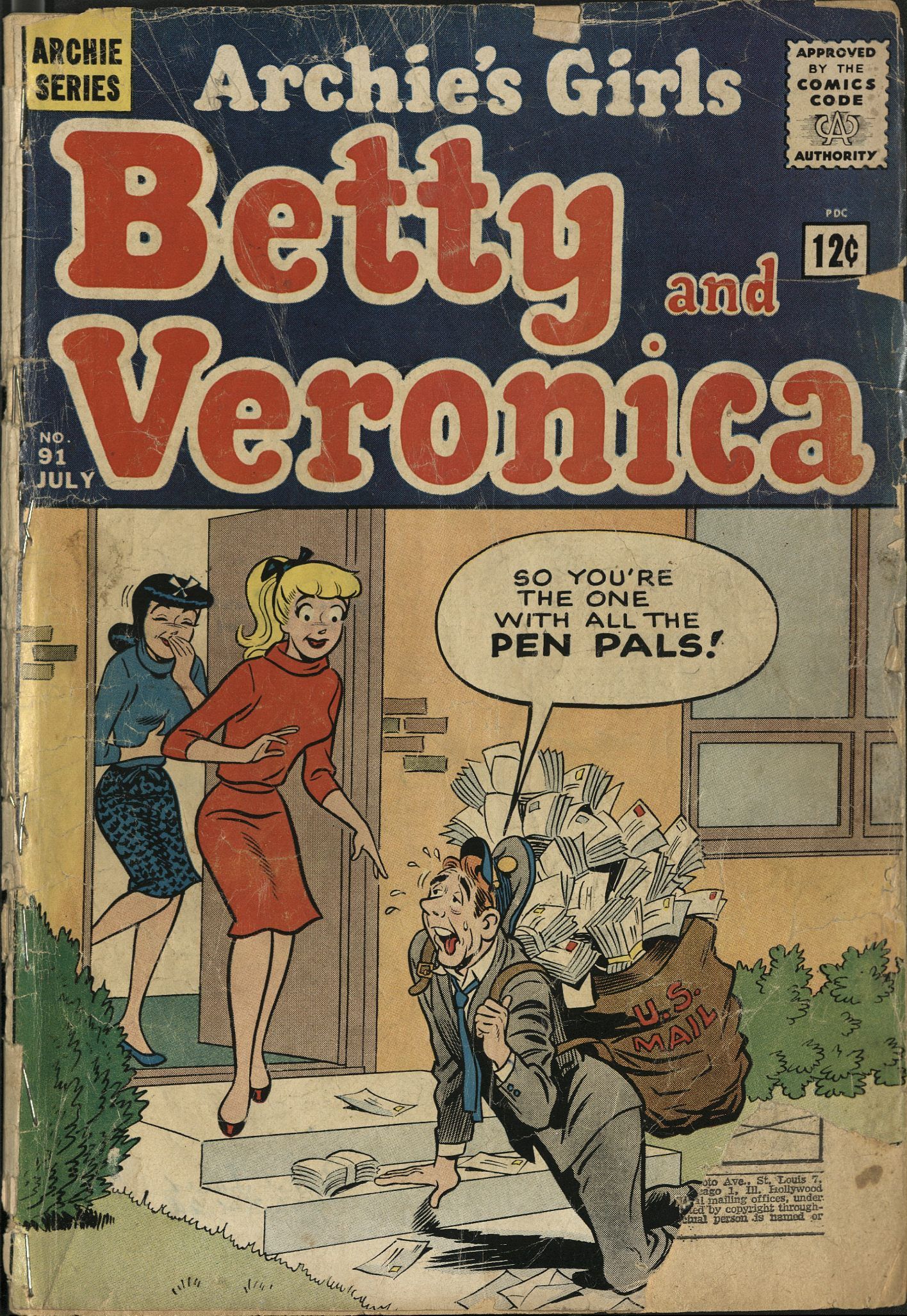

The Weird and Wonderful Things of the L. Falcon Media Fandom Collection

Zoë Webb is a graduate student at the University of Iowa in the School of Library and Information Science and is also pursuing a Book Studies certificate at the Center for the Book. As a student worker in Special Collections, she was recently appointed Processing Intern for the L. Falcon Media Fandom Collection. Below ZoëContinue reading “The Weird and Wonderful Things of the L. Falcon Media Fandom Collection”

A look at Mary Shelley the Film

This Halloween season, Frankenstein is everywhere. And no wonder, for the book turned 200 this year and is overdue for a party. While the monster is everywhere, what about the woman who created the famous story? We’ve asked our own Frankenstein expert and Curator of Science Fiction and Popular Culture, Peter Balestrieri to review theContinue reading “A look at Mary Shelley the Film”

UI Special Collections claims the Iron Throne at World Con

By Hannah Hacker Last month on August 17-21, two of our very own, Peter Balestrieri and Laura Hampton, went to represent the University of Iowa Libraries at the 74th World Science Fiction Convention, Mid AmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri. Some may wonder what a couple of Special Collections librarians were doing at aContinue reading “UI Special Collections claims the Iron Throne at World Con”

Return of the Return of the Man From U.N.C.L.E.

In September of 1964, a new series premiered on American television. It was a spy series influenced by Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels and the films that began with 1962’s, Dr. No. I was eleven years old at the time and couldn’t wait to see it. America had caught spy fever and television and HollywoodContinue reading “Return of the Return of the Man From U.N.C.L.E.”

Science Fiction Fans Raise $1,955 To Support Hevelin Collection Digitization

Every year at the ICON Science Fiction convention in Cedar Rapids the organizers collect fan created artwork, crafts, and donated memorabilia which are auctioned off to support charities and projects. Last fall, the chosen project was The University of Iowa Libraries’ initiative to digitize the James L. “Rusty” Hevelin Science Fiction collection, an especially meaningful choiceContinue reading “Science Fiction Fans Raise $1,955 To Support Hevelin Collection Digitization”