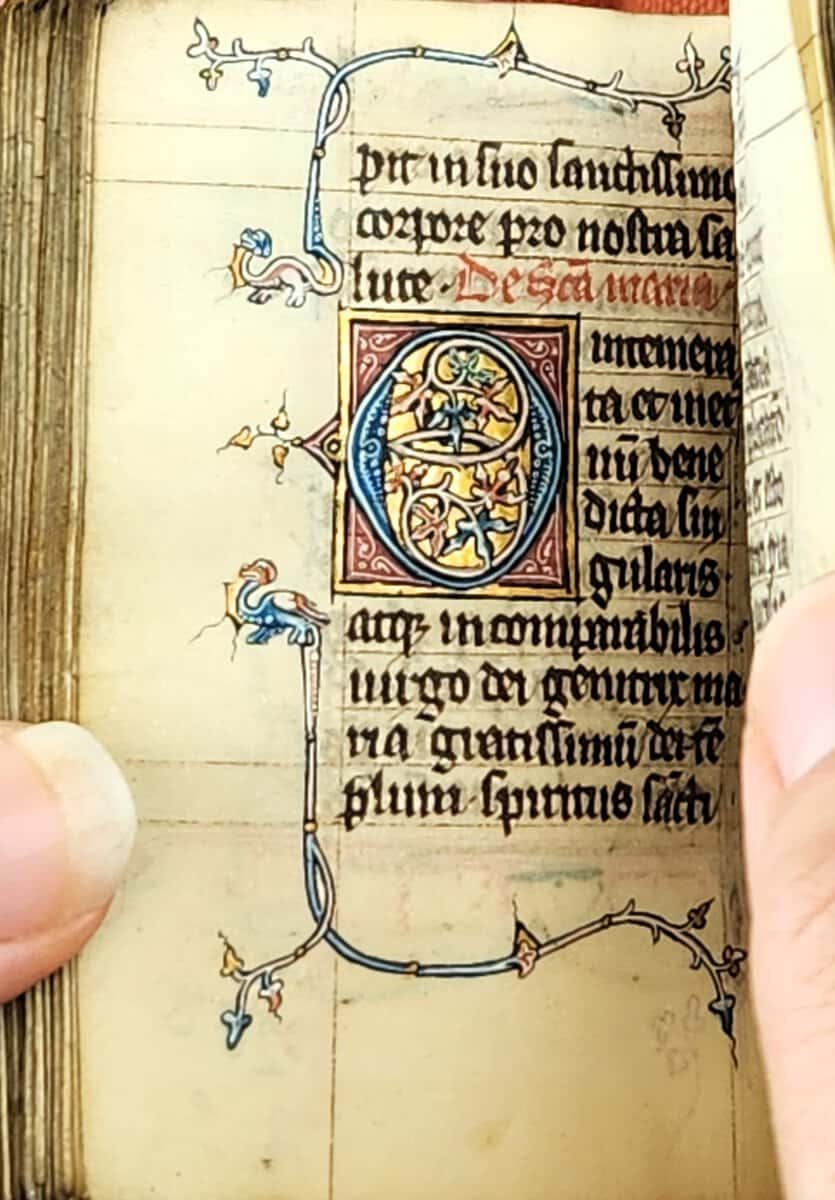

The following is written by Museum Studies Intern Joy Curry. This 14th-century book of hours may be tiny, but it is jam-packed with beasts, ranging from fish to lions to feathered dragons. It’s a marvel that so much of the art has survived, especially since the book is missing 19 miniatures. Fortunately for us, theContinue reading “Beware of marginal monsters”

Category Archives: New Acquisitions

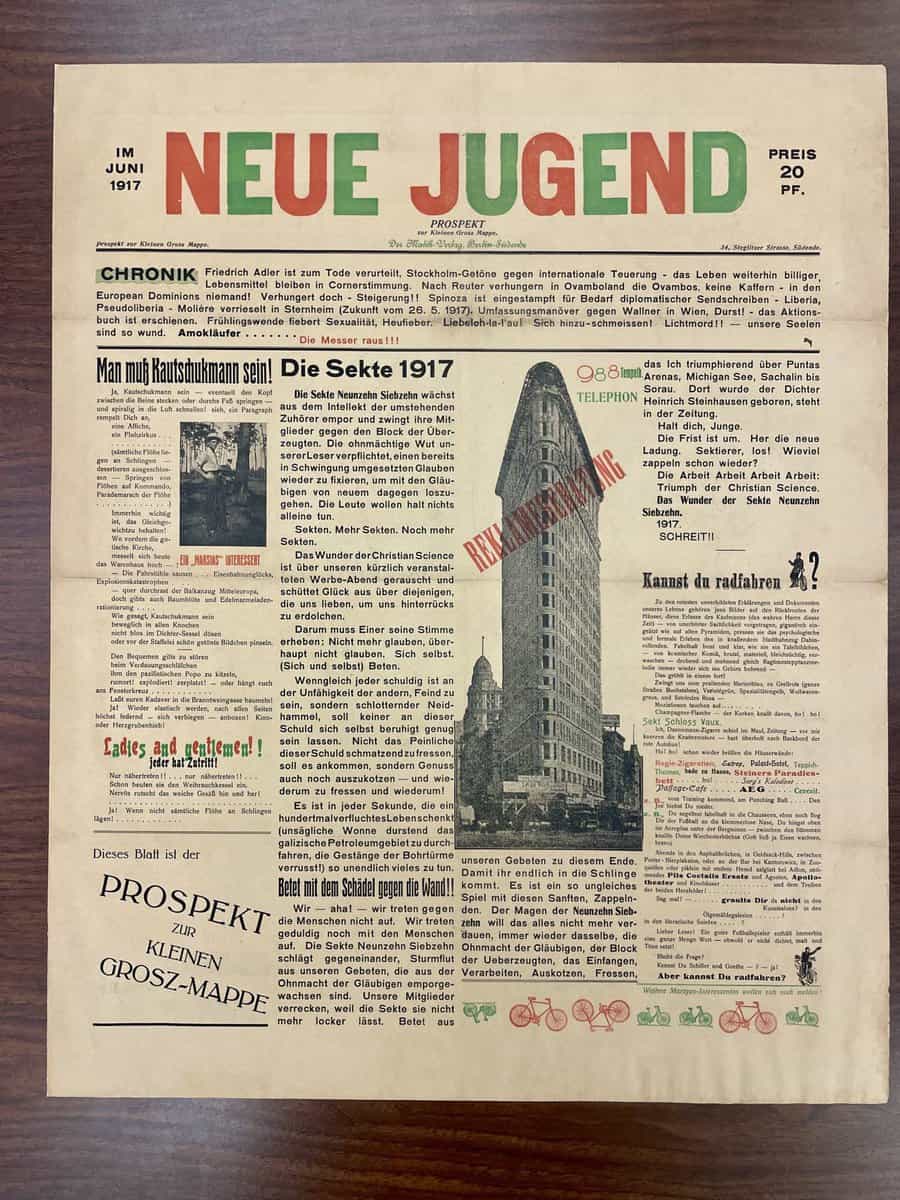

New acquisition, Neue Jugend, imparts Dada history

The following is written by curator Timothy Shipe Among the International Dada Archive’s latest acquisitions are several issues of the Berlin journal Neue Jugend, founded in early 1914 by two student poets, Heinz Barger and Friedrich Hollaender. Neue Jugend is a telling example of how the Berlin dadaists managed to elude wartime government censorship. TheContinue reading “New acquisition, Neue Jugend, imparts Dada history”

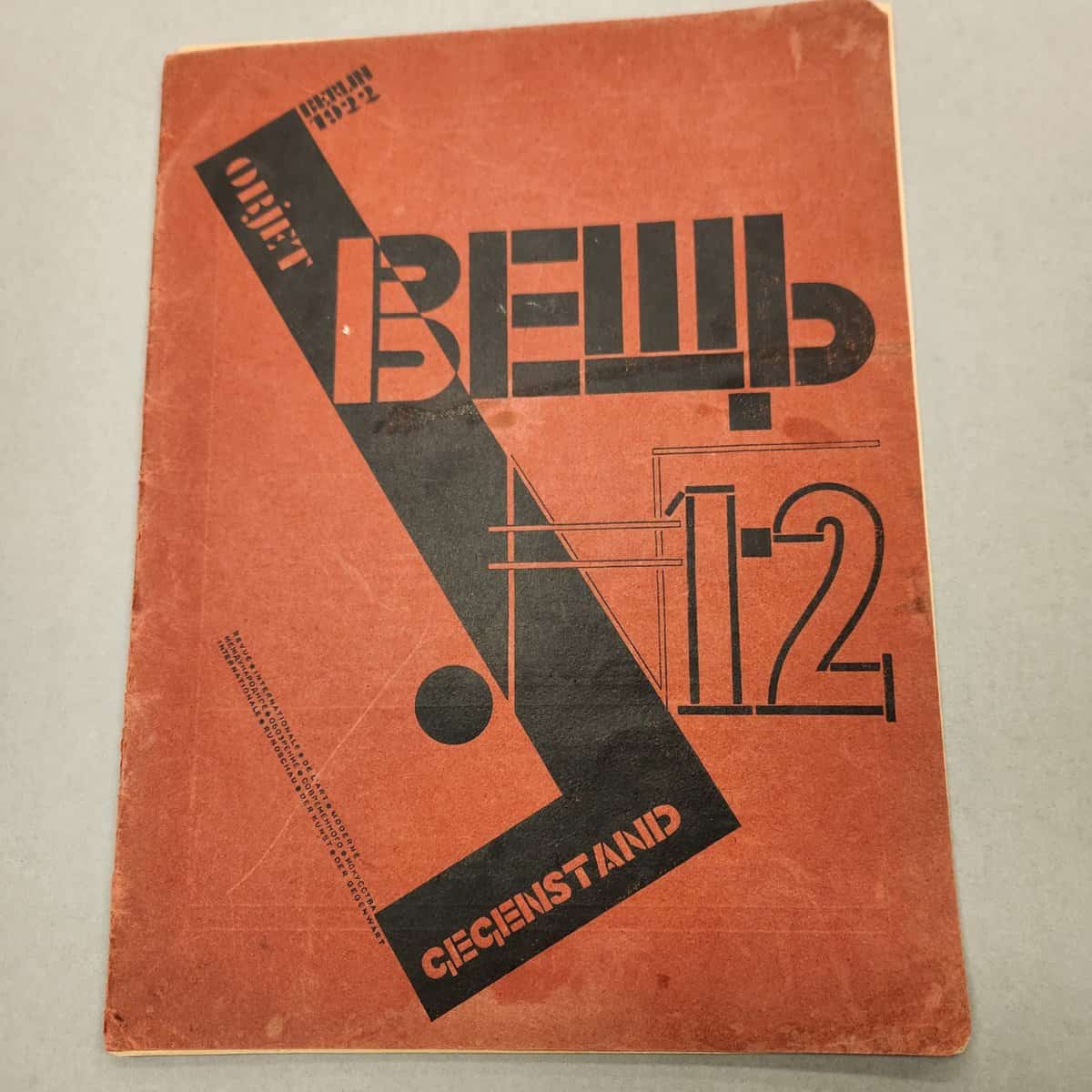

Dada collection grows

The following is written by Tim Shipe, curator of the International Dada Archive Two recent acquisitions by the International Dada Archive illustrate the diversity of Dada and its connection with the developing Central and Eastern European Constructivist movement of the 1920s. Veshch Gegenstand Objet With its trilingual title and multilingual content, Veshch Gegenstand Objet is,Continue reading “Dada collection grows”

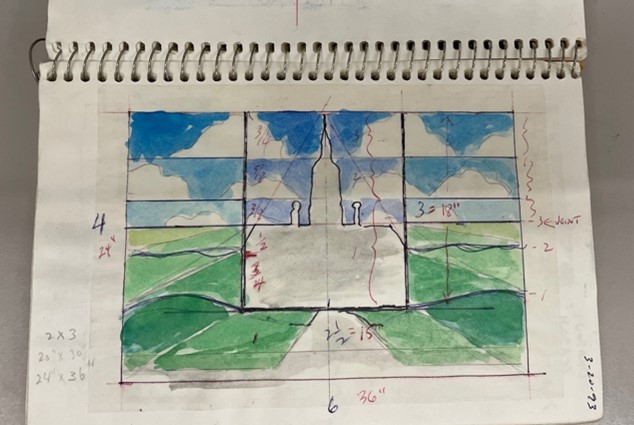

Thor Rinden: Artist’s notebooks reveal Iowa’s lasting impressions

The following is written by student worker Jack Menzies Thor Rinden was an artist born in Marshalltown, Iowa in 1937 and studied at the University of Iowa before attaining his Master of Arts at Hunter College, New York, NY. Living with his wife, Jane,the couple spent decades renovating their home in Brooklyn, which garnered substantialContinue reading “Thor Rinden: Artist’s notebooks reveal Iowa’s lasting impressions”

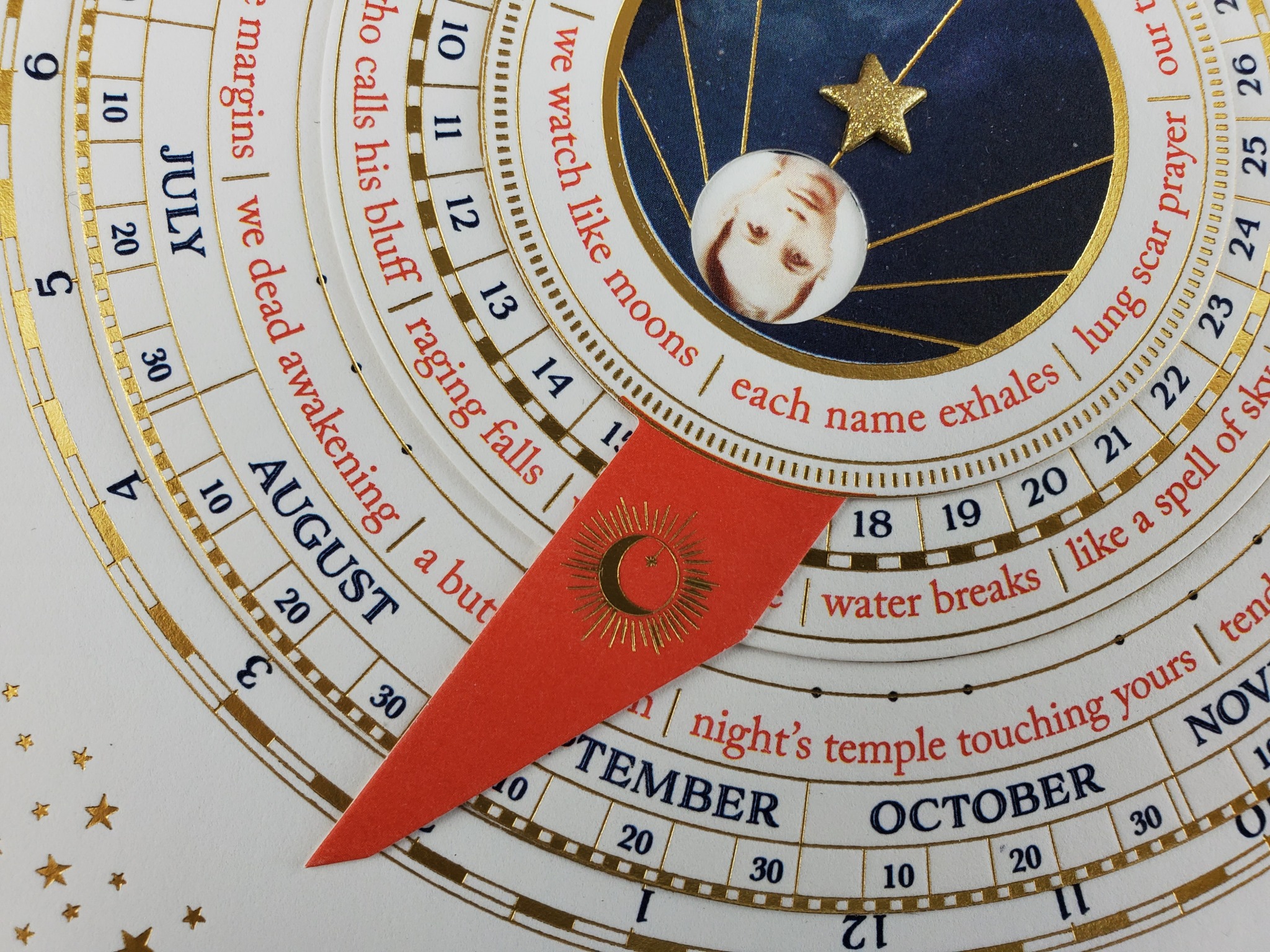

Monica Ong: An Asian-American Visual Poet

The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant Matrice Young Special Collections & Archives recently acquired two artists books from Monica Ong, a second generation Chinese-Filipino American woman born and raised in Chicago, Illinois. Her family history, like many Americans, is a complex one. During World War II, her grandparents left Fujian, China and immigrated to Manila in the Philippines. There, both of her parentsContinue reading “Monica Ong: An Asian-American Visual Poet”

The Sam Hamod Saga, Part One: Making Introductions

The following is written by graduate student Bailey Adolph, who is processing the Sam Hamod Papers. “Thus, we gain richness from our heritage—but we should not be limited as writers by our ethnicity.” — Sam Hamod, “Ethos and Ethnos: The Ethnic Writer in the USA” At the beginning of the summer, the University of IowaContinue reading “The Sam Hamod Saga, Part One: Making Introductions”

Celebrating Beatrix Potter’s Birthday with New Acquisitions

The following is written by Public Services Librarian, Lindsay Moen Today marks the 155th birthday of renowned children’s book author, Beatrix Potter. Potter was best known as the author and illustrator of cherished tales such as The Tale of Peter Rabbit, The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck, and The Tailor of Gloucester. While Peter Rabbit mightContinue reading “Celebrating Beatrix Potter’s Birthday with New Acquisitions”

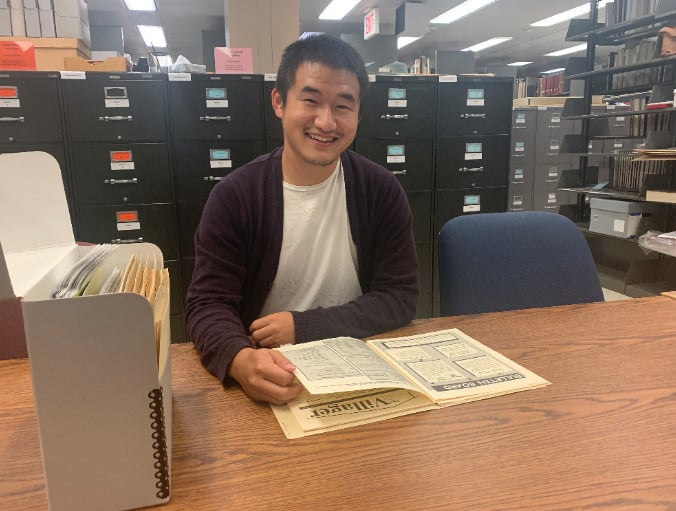

University of Iowa Asian American Oral History Archive

The following is written by Asian Alumni and Student Oral History Project Intern Jin Chang Since the start of the pandemic, prominent leaders have stood in front of crowds of American people calling COVID-19 the “China Virus” and “Kung Flu.” As a result, Chinatown businesses closed as tourists continued to avoid Chinatowns across America and raciallyContinue reading “University of Iowa Asian American Oral History Archive”

Iowa’s Medieval Manuscripts Collection Goes to the Dogs

The following was written by Curator of Books and Maps, Eric Ensley Iowa’s Medieval Manuscripts Collection has gone to the dogs, or at least to a new book with dog-themed decoration. Just in time for the tulips blooming across Iowa, our newest medieval book, a beautifully decorated book of hours, comes to us from late medievalContinue reading “Iowa’s Medieval Manuscripts Collection Goes to the Dogs”

Brokaw Papers Capture 55 Years of Journalism History

At the end of January of 2021, NBC News Anchor and Correspondent Tom Brokaw announced his retirement after a remarkable 55 years of journalism. Brokaw started his television career right here in Iowa, working at KTIV in Sioux City. He moved on KMTV in Omaha, Nebraska and then to WSB-TV in Atlanta, Georgia. By 1966,Continue reading “Brokaw Papers Capture 55 Years of Journalism History”