This series features the work and research of UI students. The following is written by Larisa Greway, a museum studies intern at Special Collections and Archives. If you can read a piece of sheet music, you’ve benefited from over a thousand years of evolution. In the Middle Ages, music not only sounded, but looked muchContinue reading “Students investigate: the materiality of medieval music”

Category Archives: Collection Connection

Students investigate: the surprisingly long story of how Kinnick Stadium got its name

This series features the work and research of UI students. The following is written by Calvin Covington, Olson graduate research assistant. I’d wager that, even if they haven’t gone to a game, most of Iowa City’s population has borne witness to the grand Kinnick Stadium, where, every football season, legions of fans flock to watchContinue reading “Students investigate: the surprisingly long story of how Kinnick Stadium got its name”

Highlights from Lunch with the Chefs, corn edition

The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant Anne Moore. It’s corn sweat season! Check out this top 10 list of corn-themed materials from Special Collections and Archives, which were on display last month at the Iowa Memorial Union (IMU)’s Lunch with the Chefs. This event is a special, themed lunch hosted by UniversityContinue reading “Highlights from Lunch with the Chefs, corn edition”

Form and symbolism in Pam Spitzmueller’s tarot decks

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit Special Collections and Archives at the University of Iowa Libraries. Below is a blog by Andrew Newell from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “Reading Culture History & Research in Media” (SLIS:5600:0EXW). Newell explores the history, use,Continue reading “Form and symbolism in Pam Spitzmueller’s tarot decks”

A king by any other name would die as duly, or the top 10 nicknames of Louis XVI

The following is written by Libraries student employee Brianna Bowers. The few short months from the fall of 1792 to January 1793, in which heated debate and a final vote decided that Louis XVI would be guillotined, held centuries of progress. Our world would not be recognizable without the French Revolution. The University of IowaContinue reading “A king by any other name would die as duly, or the top 10 nicknames of Louis XVI”

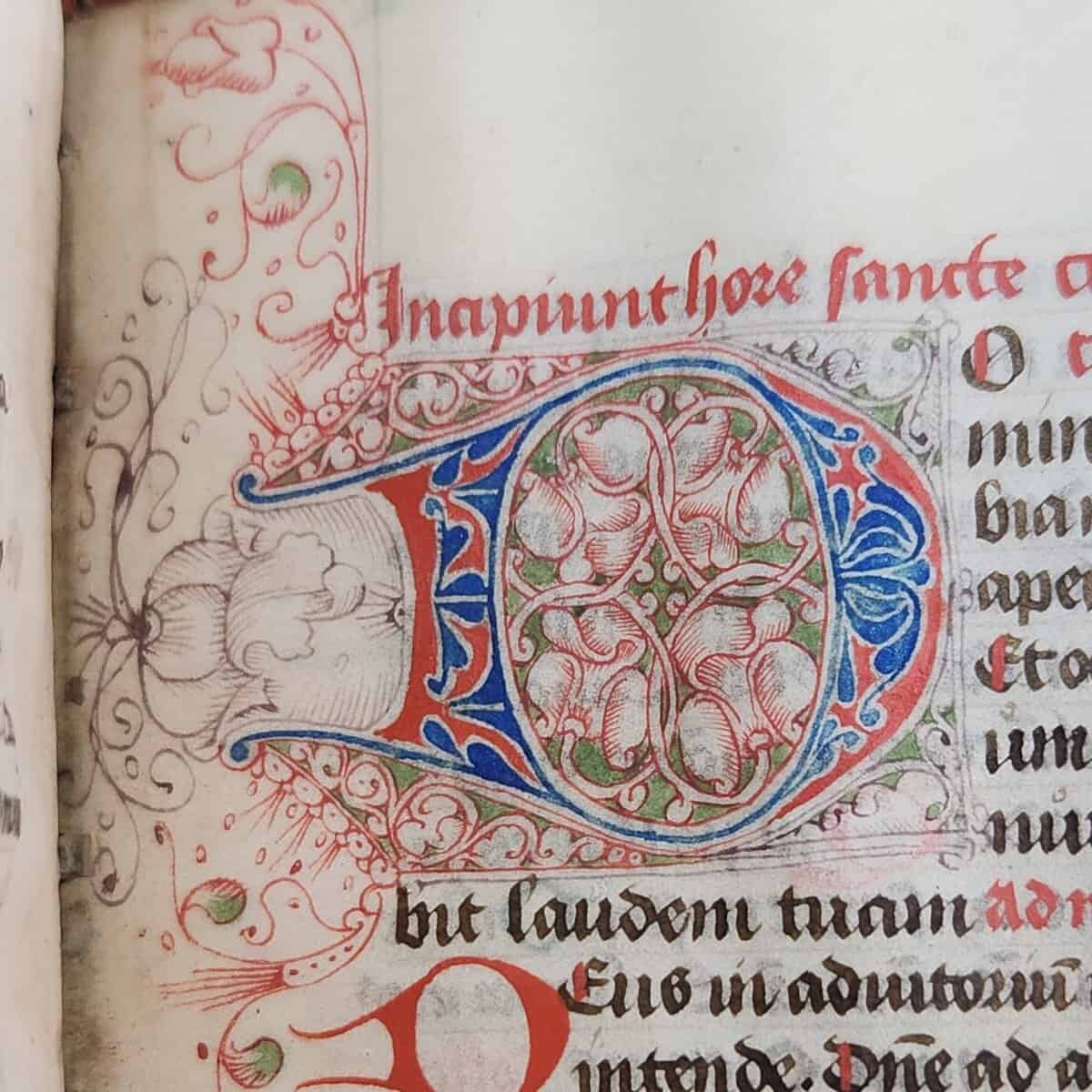

Versals from a 15th-century Book of Hours, in order of increasing fanciness

The following is written by Museum Studies Intern Joy Curry If medieval scribes knew one thing, it was the importance of fancy letters. Surviving manuscripts are decorated with gold, filigree, intricate paintings, and more methods to make the words as beautiful as possible. One type of decoration was versals: letters that are drawn rather thanContinue reading “Versals from a 15th-century Book of Hours, in order of increasing fanciness”

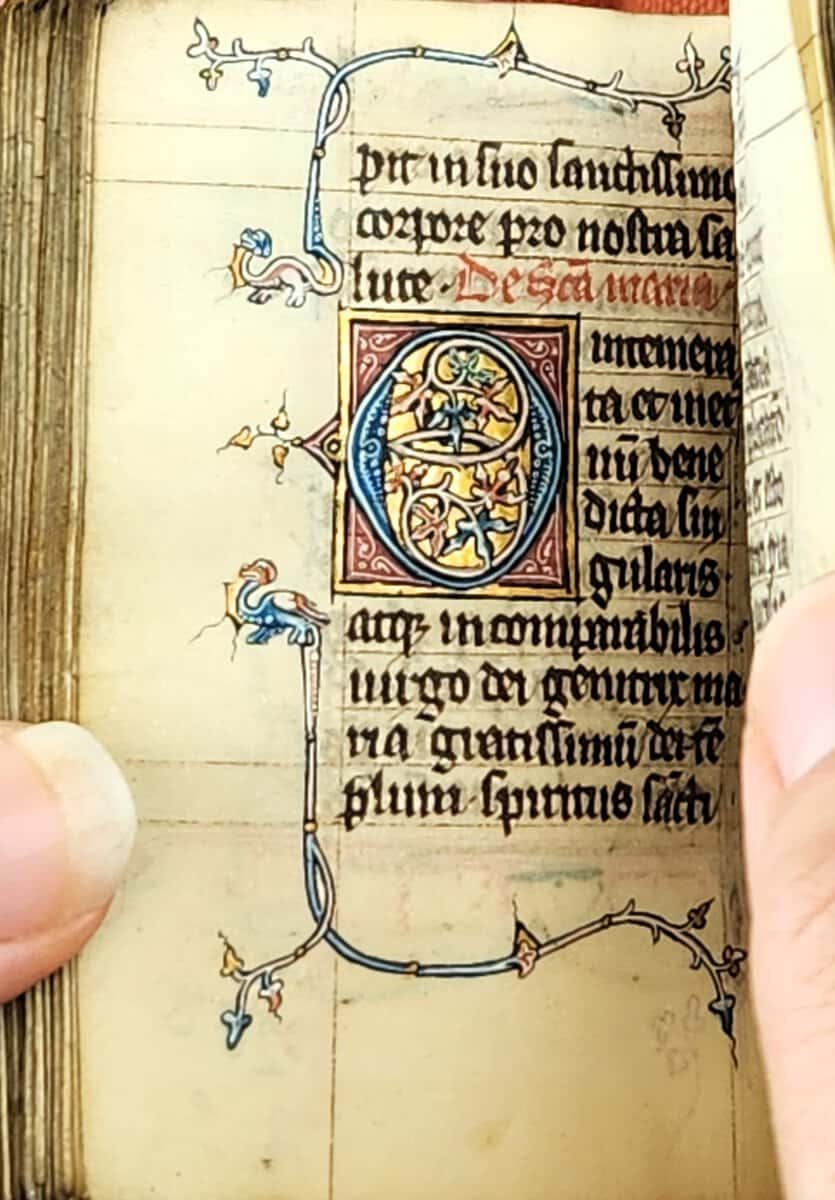

Beware of marginal monsters

The following is written by Museum Studies Intern Joy Curry. This 14th-century book of hours may be tiny, but it is jam-packed with beasts, ranging from fish to lions to feathered dragons. It’s a marvel that so much of the art has survived, especially since the book is missing 19 miniatures. Fortunately for us, theContinue reading “Beware of marginal monsters”

Voices from the stacks: Corita Kent

The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant, Kaylee Swinford. Corita Kent was an American artist, educator, activist, and former religious sister. With a rebellious spirit, Corita was a pioneering designer, who produced a body of work for over three decades combining themes of spirituality, hope, peace, and acceptance. Inspired by the popular PopContinue reading “Voices from the stacks: Corita Kent”

Language of flowers speaks volumes

The following is written by museum intern student Joy Curry. Valentine’s Day is, among other things, a common time to give and receive flowers. If you visited a florist this last holiday, you might have seen some explanations on what flowers mean. You may have heard of the symbolism attached to different colors of rosesContinue reading “Language of flowers speaks volumes”

Voices from the Stacks: Phillip G. Hubbard

The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant Anne Moore. Phillip G. Hubbard was an engineering professor, administrator, civil rights champion, and distinguished member of the University of Iowa community. He was the first Black professor at the university and spent more than 40 years advocating for students and providing counsel to sixContinue reading “Voices from the Stacks: Phillip G. Hubbard”