“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Breanna Himschoot from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0001) Cookbooks, Citation, and Community By Breanna Himschoot Under its bright lavender marbled binding, this handwrittenContinue reading “Cookbooks, Citation, and Community”

Tag Archives: szathmary

Szathmary inspiration for the perfect slice of pie

Our Archives Assistant Denise Anderson explored the Szathmary collection to create the perfect cherry pie. Below is the recipe, along with Denise’s step-by-step guide on what she did to create what is sure to be the best dessert at your next Thanksgiving. Time to make a Betty Crocker fresh fruit (in this case cherry) pieContinue reading “Szathmary inspiration for the perfect slice of pie”

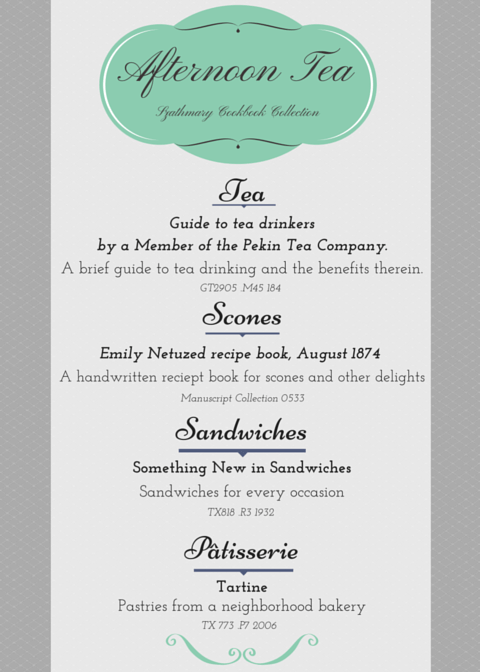

Sample the Szathmary Culinary Collection

Feeling overwhelmed by the more than 20,000+ cookbooks from 1498 to the present day, thousands of recipe pamphlets, and multitudes of handwritten cookbooks? Sample an item from a tasting menu. Just stop by the Reading Room on the 3rd floor of the Main Library and order up a culinary item to browse from one ofContinue reading “Sample the Szathmary Culinary Collection”

Historic Foodies, Talk of Iowa, and Marlborough Pudding/Pie

Thank you to all who attended last week’s first meeting of the Historic Foodies! For those of you who missed the meeting, Kathrine’s Moermond from the Old Capitol Museum told tales of tracking down the variations of Marlborough Pudding. I’ve included her account here and hear her tell some of the tale on this week’sContinue reading “Historic Foodies, Talk of Iowa, and Marlborough Pudding/Pie”

Happy Thanksgiving!

This morning I was a guest on Iowa Public Radio’s Talk of Iowa program, where we discussed Thanksgiving recipes, cookbooks, and traditions. You can listen to an archived version of the program here. Below are links to some of the items from Special Collections that were discussed on the show. Szathmary Culinary Manuscripts: http://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/cookbooks DIYContinue reading “Happy Thanksgiving!”

Want to Make Historic Recipes?

Want to make historic recipes? Or how about reading handwriting, converting measurements, recreating historic cooking implements, food photography, or writing and blogging? 300+ years of handwritten cookbooks with thousands of recipes from Chef Louis Szathmary’s culinary collection from Special Collections & University Archives are now online in DIY History, the newest transcription project from theContinue reading “Want to Make Historic Recipes?”