“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Breanna Himschoot from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0001)

Cookbooks, Citation, and Community

By Breanna Himschoot

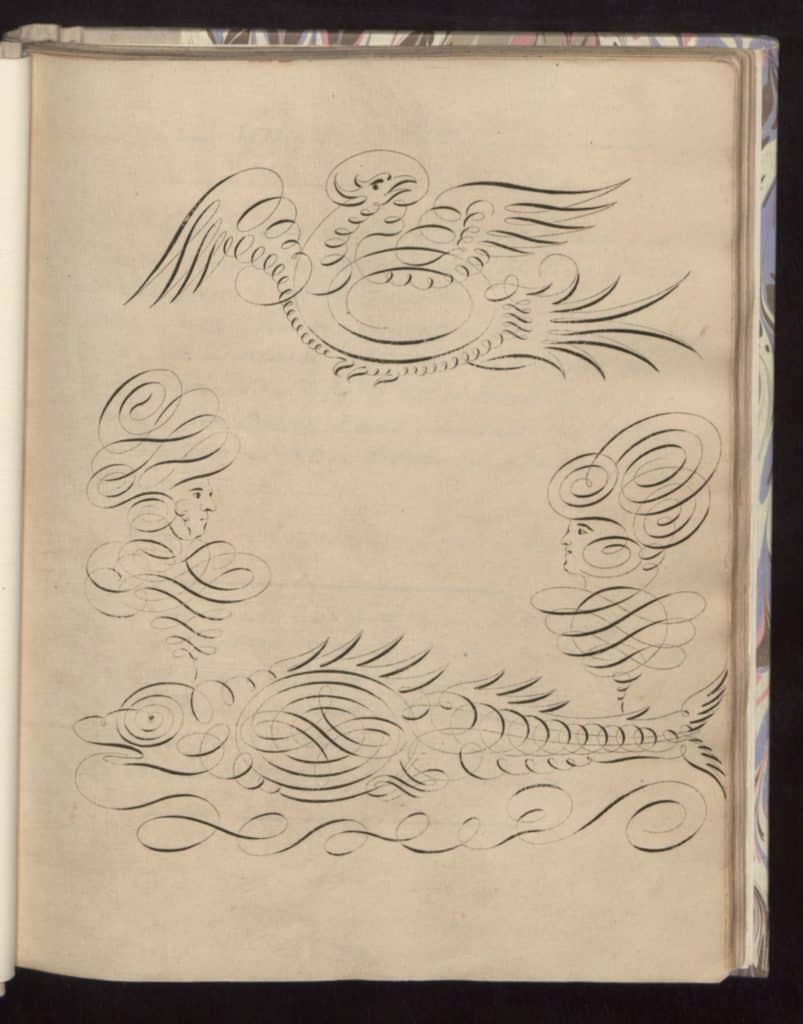

Under its bright lavender marbled binding, this handwritten American cookbook (American cookbook, ca. 1850, US32 in the Szathmary Culinary Manuscripts Collection at the University of Iowa) holds a world of community and relationships, even though the two writers of the book are unknown to us. Given the context of its recipes and handwriting, we believe this book to have been written by two women in America, in the years following 1851. Though the first page contains penned illustrations fit for a cover page, this book has no self-prescribed title or mention of the names of the women who wrote it. Yet, we can learn about these women through their interactions with the book itself.

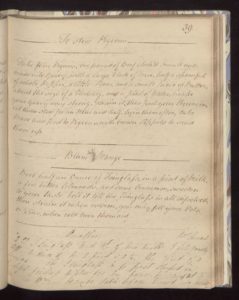

In the hand of the first writer, the text is formatted consistently throughout, with numbered pages that leave extra room to fill in before a roughly alphabetic index relating page number to recipe. This neat and practical formatting, paired with her recipe for Harvey’s Fish Sauce (page 17) copied from Miss Leslie’s Directions for Cookery (1851), suggests that the first writer has at least some familiarity with printed books, and cookbooks especially. She also uses the pages of this cookbook to comment on her own recipes, noting her preference of one pea soup over another and adding tips based on her experience using the recipes she records.

Our second writer is much less neat and is unafraid to scribble through, and write over her own writing. She begins filling in her new recipes in any space she can find before she reaches the previously unfilled pages (page 50). Though our first writer did occasionally attribute her recipes to others (Mrs. Downe’s raisin wine on page 35 and Mr. Pendrill’s rec’t when a barrel of beer turns sour on page 46 for example), our second writer is much more likely to attribute her recipes to named people. Over the course of her writing, she names the sources of at least 59 of her recipes, with a Mrs. Saward (often abbreviated to Mrs. S) having a notable number of contributions. Mrs. Saward is the citation for almost every recipe from pages 98-104, 23 in total. Could our unnamed writer have been visiting her and consulting her favorite recipes together, perhaps copying them from Mrs. S’s own cookbook? Was she a friend, mentor, or relative? These names, especially when looking at how they appear in the text, give us a sense of the community that this unnamed second writer lived in, and allow us to speculate on her interactions in this community.

Though we cannot be sure of the second writer’s relationship to the first, we can see in these pages an engagement with the recipes that the first writer recorded. From correcting her spelling of “spinach” (page 43), striking through recipes in the index, and pasting over the recipe for Hunter’s pudding with a recipe for Plum pudding instead (6), we see this text being used, updated, and commented on. Beyond its written engagements, the staining on certain pages point to this book having an active life the kitchen rather than remaining a pristine set of records. Though we may never know these women’s names, perhaps by spending time among their notes and the pages they stained, we can learn more about the community they lived in and the recipes they valued.

Further reading:

Theophano, Janet. 2002. Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives through the Cookbooks They Wrote. New York: Palgrave.