Last week we opened, for the first time, a wooden shipping crate that had been stored in the department for many years. It had been sent to the Libraries in 1986 by Desmond Leigh-Hunt, the great-great-grandson of the Romantic poet and editor Leigh Hunt. Desmond Leigh-Hunt described it in correspondence as the fireplace surround from the last home Leigh Hunt lived in, at 16 Rowan Road in Hammersmith, London. He included a document signed by Rodney Tatchell, a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, asserting its authenticity and dating it to the early 1840s. After it arrived the crate was stored, unopened, primarily in the basement of the Main Library.

In 2012 we moved all of our departmental collections out of the basement to the third floor, including the 300 pound crate. We resolved to open it and examine its contents, and the winter doldrums of January seemed the perfect time to do so. The opening and unpacking is well documented in photos, which can be viewed on Flickr.

We have managed to arrange some of the pieces into an approximation of what the fireplace surround might have looked like, but what does this piece tell us about Leigh Hunt? Does it bring us closer to the real person whose books and manuscripts line our shelves?

To tell the story, we start back in the presence of Rodney Tatchell, whose signature affirms the statement about the fireplace surround at the time of its removal from the house. Tatchell was a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and he lived at 22 Rowan Road, the same street as Leigh Hunt’s old house. His wife, Molly Tatchell, shared his interest in their historical neighbor—in 1969 she published a book through the Hammersmith Local History Group entitled Leigh Hunt and His Family in Hammersmith. Her book provides an account of the final years of Leigh Hunt’s life, and includes detailed descriptions of his house at 16 Rowan Road (known as 7 Cornwall Road in Hunt’s time):

“[Regarding the cottages] no two are exactly the same. One type has two small reception rooms on the ground floor divided by a passage with staircase, the other has two larger rooms connected by double doors, so that they can be thrown into one: Leigh Hunt’s was one of this type. They have three or four bedrooms, the small one over the kitchen now being usually converted into a bathroom. The houses originally had, of course, no bathroom, and the privy was situated outside, near the back door.

“Such was Leigh Hunt’s simple, but not undignified, last home. Some of his visitors were to describe it in unflattering terms, but from what we can see of it today, and from what we know of its surroundings in the mid-nineteenth century, it cannot have been an unpleasant place in which to end one’s days.” [p. 10]

Leigh Hunt and his wife Marianne moved to Hammersmith in 1853, leaving behind a house in Kensington steeped in the memories of a deceased son, and into a house near other family already settled in the area. Leigh Hunt was 69, had made peace with many of his former foes, and finally could rely on a relatively secure income. Marianne, however, was by this time entirely bed-ridden, and remained so until her death in 1857. As he aged, Hunt took on the air of an esteemed elder statesman of letters, in contrast to his youthful rebellion. He welcomed visitors to the house at 16 Rowan Road, including those who travelled from afar to see him, such as Nathanial Hawthorne.

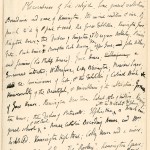

One of Hunt’s visitors in Hammersmith was Charles Dickens, who had bitterly wounded Hunt with his portrayal as Harold Skimpole in Bleak House. The two had reconciled their differences, however, and Dickens visited Hunt on July 3, 1855. The following day, he wrote to his longtime friend Charles Ollier:

“I had got my new book ready packed to bring you, and the volume containing the passage about Watteau, and an account of some delightful hours which Dickens gave me here yesterday evening; and at a quarter to six o’clock, was obliged to give all up. “

“P.S.—By a curious effect of the evening sunshine, my little black mantle-piece, not an inelegant structure, you know in itself, is turned, while I write, into a solemnly gorgeous presentment of black and gold. How rich are such eyes as yours and mine, how rich and how fortunate, that can see visitations so splendid in matters of such nine-and-twopence!” [The Correspondence of Leigh Hunt, 1862, p. 203]

Now the pieces of black slate with inlaid marble here in Special Collections are tied directly back to Leigh Hunt. He would have been in the front room of his house, the window facing west, allowing the late afternoon sun to shine in and strike the fireplace surround. Curiously, it seems as though we have two complete fireplace surrounds, suggesting that there could have been openings in two rooms sharing a common chimney. This might be reasonable given Molly Tatchell’s description of the house’s layout, “two larger rooms connected by double doors, so that they can be thrown into one.”

For now, the pieces of Leigh Hunt’s fireplace will likely be re-housed in more stable materials, perhaps stored in several boxes rather than one very heavy crate. They will join some of the letters of Leigh Hunt, or the manuscript for Old Court Suburb—other material traces of Hunt’s time in his modest home in Hammersmith, at the end of a remarkable life. Perhaps some future renovation of Special Collections will include room to properly display the fireplace surrounds—but surely that is a matter of nine-and-twopence!

Molly Tatchell’s book Leigh Hunt and His Family in Hammersmith is still available from the Fulham and Hammersmith Historical Society’s website.