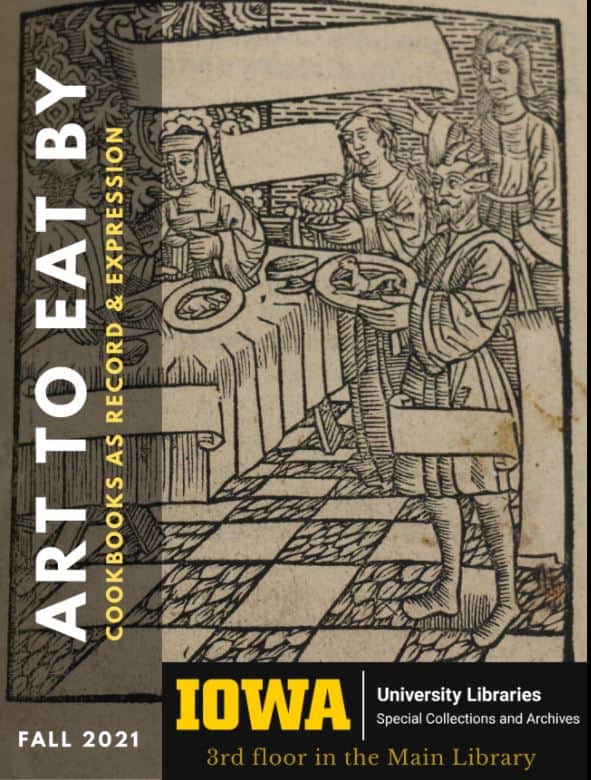

The following Top 10 List is written by graduate student worker Diane Ray, with introduction by Curator Eric Ensley. Images, unless otherwise noted, are also from Diane. Eric and Diane co-curated the exhibit “Art to Eat By: Cookbooks as Record and Expression” which is on display in the Special Collections & Archives reading room SeptemberContinue reading “Art to Eat By: Cookbooks as Record and Expression”

Tag Archives: Eric Ensley

Iowa’s Medieval Manuscripts Collection Goes to the Dogs

The following was written by Curator of Books and Maps, Eric Ensley Iowa’s Medieval Manuscripts Collection has gone to the dogs, or at least to a new book with dog-themed decoration. Just in time for the tulips blooming across Iowa, our newest medieval book, a beautifully decorated book of hours, comes to us from late medievalContinue reading “Iowa’s Medieval Manuscripts Collection Goes to the Dogs”

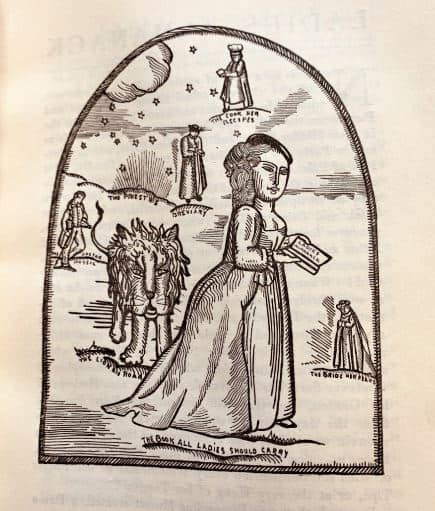

Djuna Barnes’ Ladies Almanack: An almanac like no other

The following is written by Curator of Books and Maps Eric Ensley March is women’s history month, and it feels appropriate to turn towards the work of a great writer from the early twentieth century, Djuna Barnes. Barnes is well known to students of gender and sexuality, particularly for her literary work that broached theContinue reading “Djuna Barnes’ Ladies Almanack: An almanac like no other”

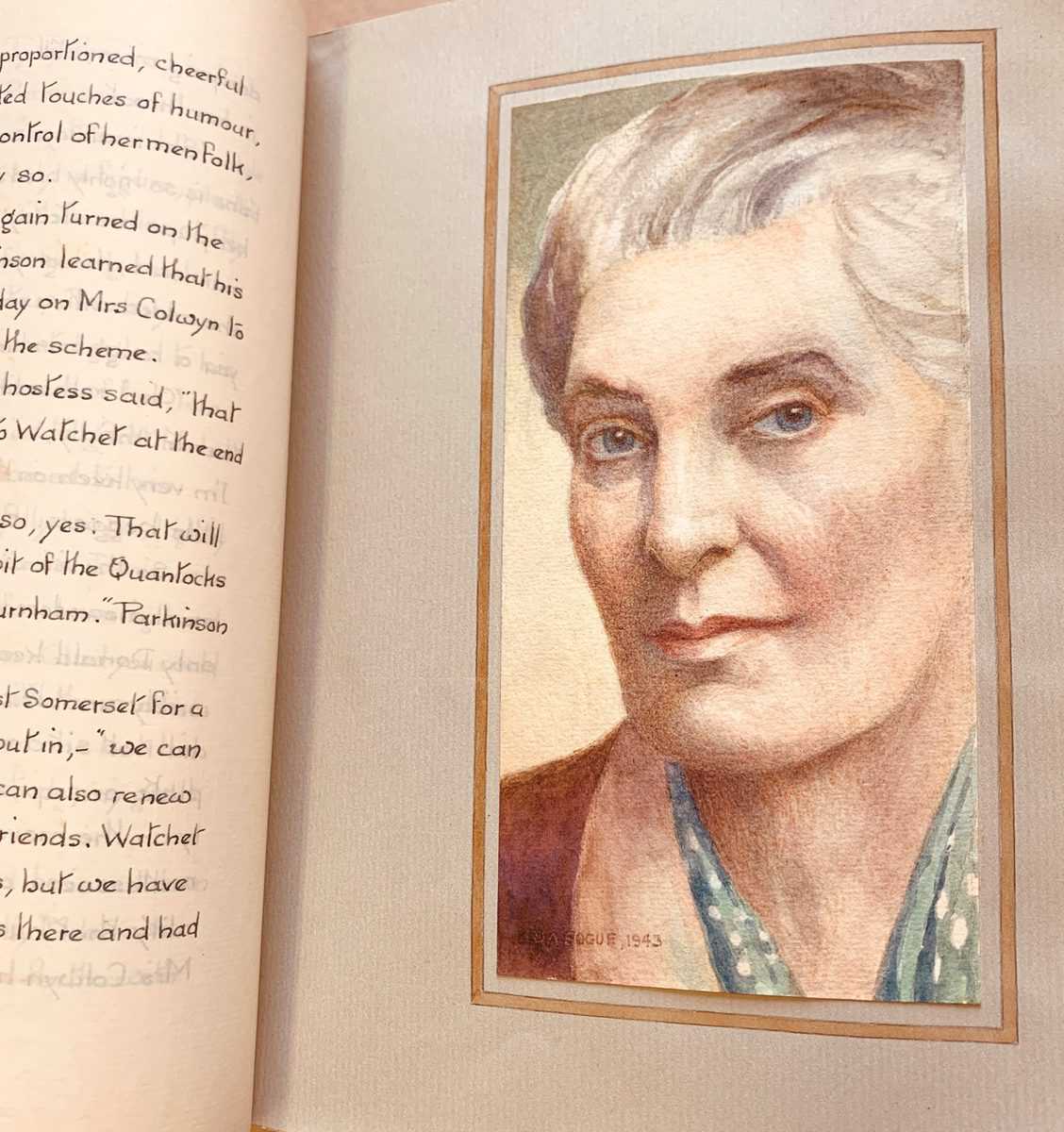

Ida Bogue’s Handmade Adventure

The following was written by Curator of Books and Maps Eric Ensley As the snow begins to melt away in Iowa City, happily we begin to think of nature and adventures along the hills and riverbanks of the countryside. This desire for spring is felt all the more as we live through times of lossContinue reading “Ida Bogue’s Handmade Adventure”

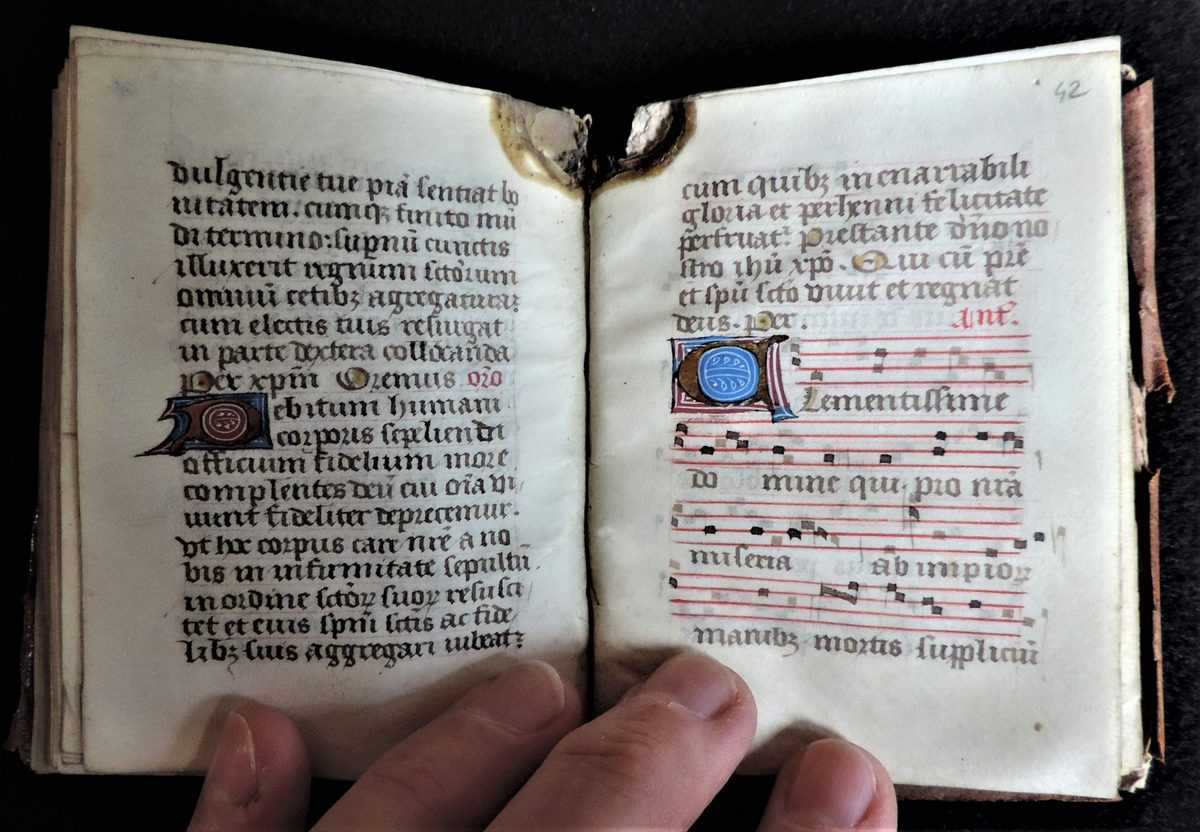

A New Processional, from Poissy to the Prairie

The following comes from Book and Maps Curator, Eric Ensley A perennial question for students of the Middle Ages is how and what did women read. The newest addition to our collection of medieval manuscripts answers this question at least in one place and moment. This diminutive book from the first half of the sixteenthContinue reading “A New Processional, from Poissy to the Prairie”

Dr. Eric Ensley joins Special Collections

On December 28th, 2020, Dr. Eric Ensley will join Special Collections as Curator of Books and Maps. Ensley earned his MSLS from UNC before going on to earn an MA in English from NCSU, then an MA, M.Phil., and PhD in English from Yale. While at Yale, he worked in the Beinecke Library as aContinue reading “Dr. Eric Ensley joins Special Collections”