This series features the work and research of UI students. The following is written by Larisa Greway, a museum studies intern at Special Collections and Archives. If you can read a piece of sheet music, you’ve benefited from over a thousand years of evolution. In the Middle Ages, music not only sounded, but looked muchContinue reading “Students investigate: the materiality of medieval music”

Category Archives: Educational

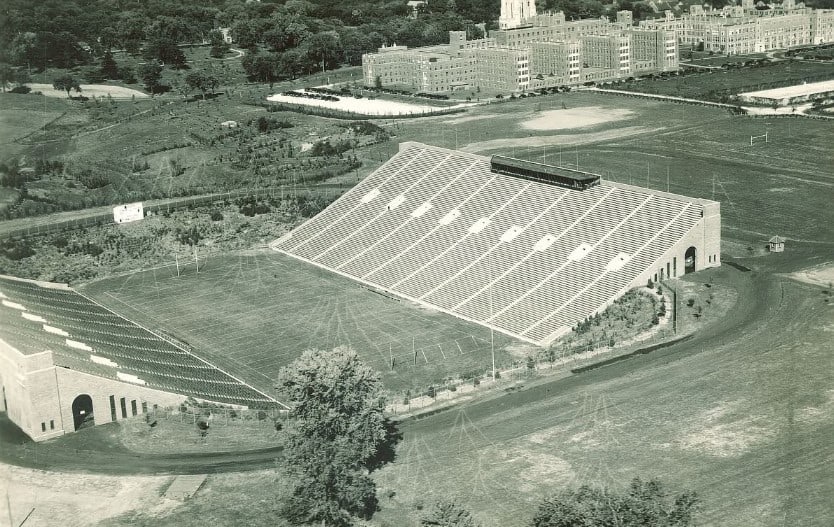

Students investigate: the surprisingly long story of how Kinnick Stadium got its name

This series features the work and research of UI students. The following is written by Calvin Covington, Olson graduate research assistant. I’d wager that, even if they haven’t gone to a game, most of Iowa City’s population has borne witness to the grand Kinnick Stadium, where, every football season, legions of fans flock to watchContinue reading “Students investigate: the surprisingly long story of how Kinnick Stadium got its name”

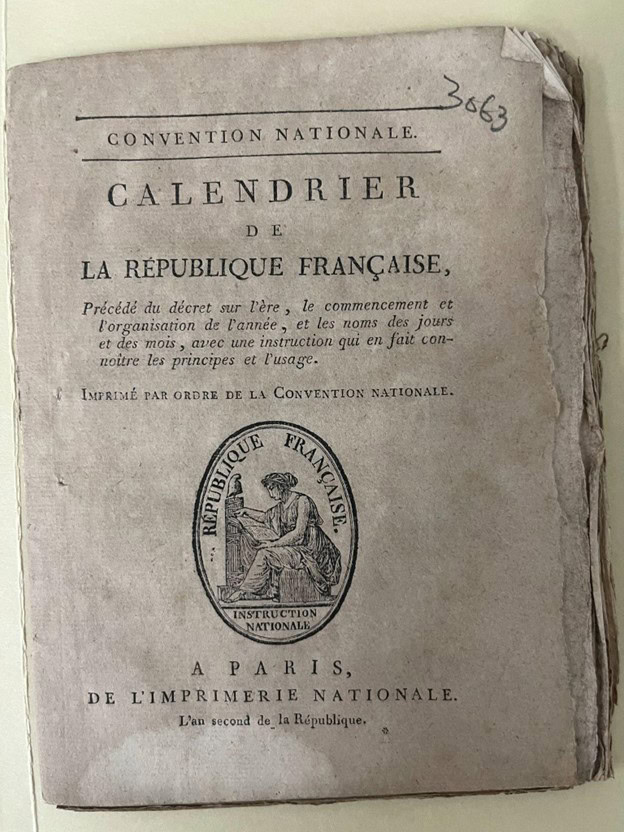

Students Investigate: New Year, new France

This series features the work and research of UI students. The following is written by Brianna Bowers, student worker for Special Collections and Archives. Have you ever made a New Year’s resolution or used the turning of the calendar to wipe a clean slate for yourself? These resolutions can be effective at creating new habits,Continue reading “Students Investigate: New Year, new France”

Form and symbolism in Pam Spitzmueller’s tarot decks

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit Special Collections and Archives at the University of Iowa Libraries. Below is a blog by Andrew Newell from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “Reading Culture History & Research in Media” (SLIS:5600:0EXW). Newell explores the history, use,Continue reading “Form and symbolism in Pam Spitzmueller’s tarot decks”

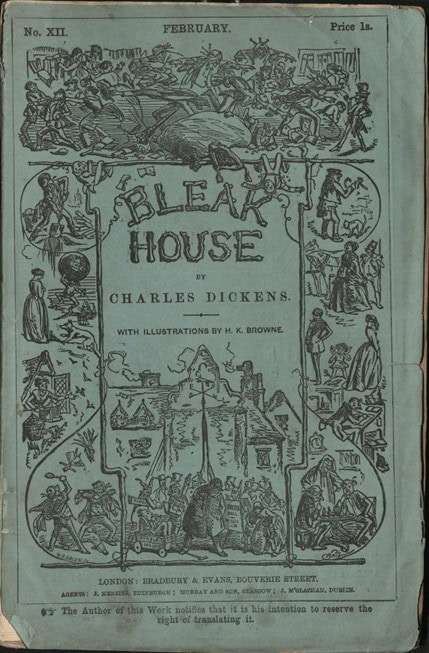

Stepping into the bustling world of Bleak House’s first readers

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit Special Collections and Archives at the University of Iowa Libraries. Below is a blog by Casie Minot from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “Reading Culture History & Research in Media” (SLIS:5600:0EXW). Minot explores the paratext ofContinue reading “Stepping into the bustling world of Bleak House’s first readers”

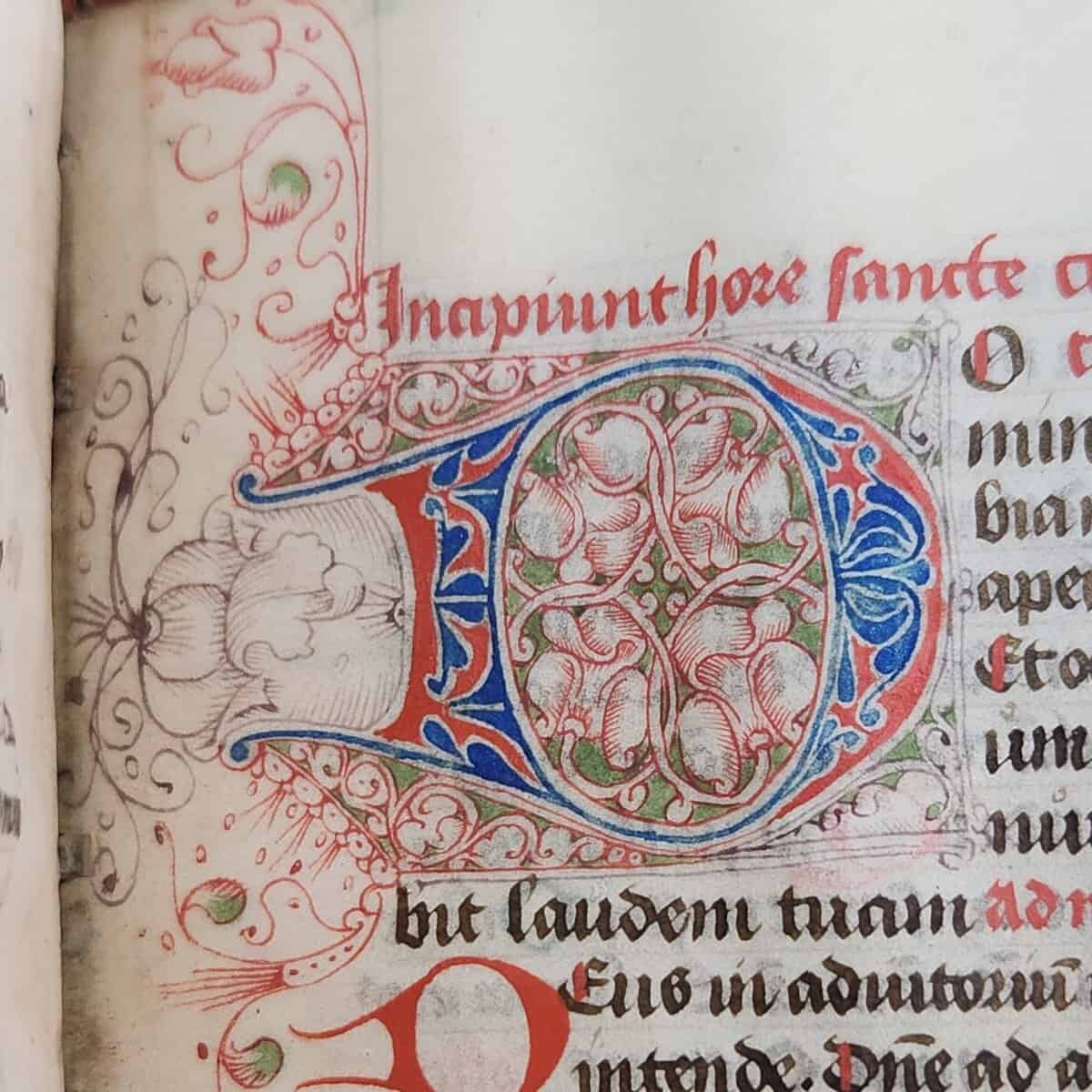

Versals from a 15th-century Book of Hours, in order of increasing fanciness

The following is written by Museum Studies Intern Joy Curry If medieval scribes knew one thing, it was the importance of fancy letters. Surviving manuscripts are decorated with gold, filigree, intricate paintings, and more methods to make the words as beautiful as possible. One type of decoration was versals: letters that are drawn rather thanContinue reading “Versals from a 15th-century Book of Hours, in order of increasing fanciness”

Art From Tragedy: Mauricio Lasansky’s The Nazi Drawings

The following is written by Academic Outreach Coordinator Kathryn Reuter Mauricio Lasanky was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1914 to Jewish immigrants from Lithuania. Lasansky showed artistic skill from a young age — printmaking was his preferred medium, a choice perhaps influenced by his father, who worked as a printer of banknote engravings. AfterContinue reading “Art From Tragedy: Mauricio Lasansky’s The Nazi Drawings”

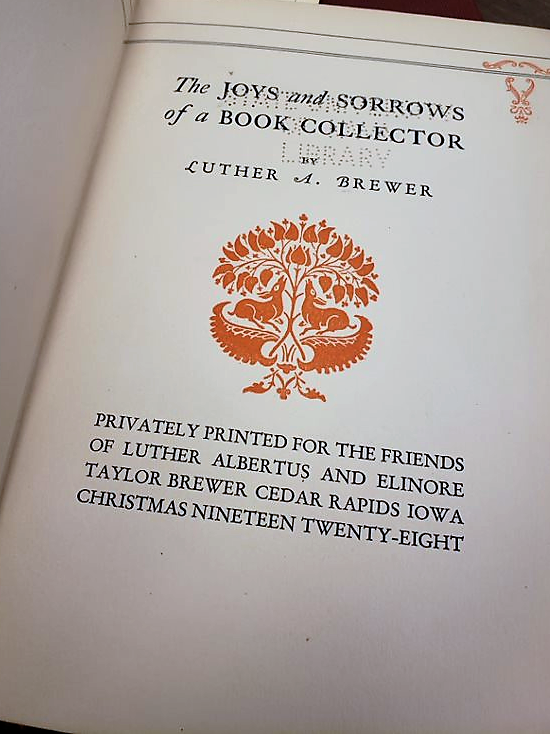

It isn’t hoarding if it’s books – or is it?

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Lisa Tuzel from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “Reading Culture History & Research in Media” (SLIS:5600:0001). It isn’t hoarding if it’s books – or is it? By Lisa TuzelContinue reading “It isn’t hoarding if it’s books – or is it?”

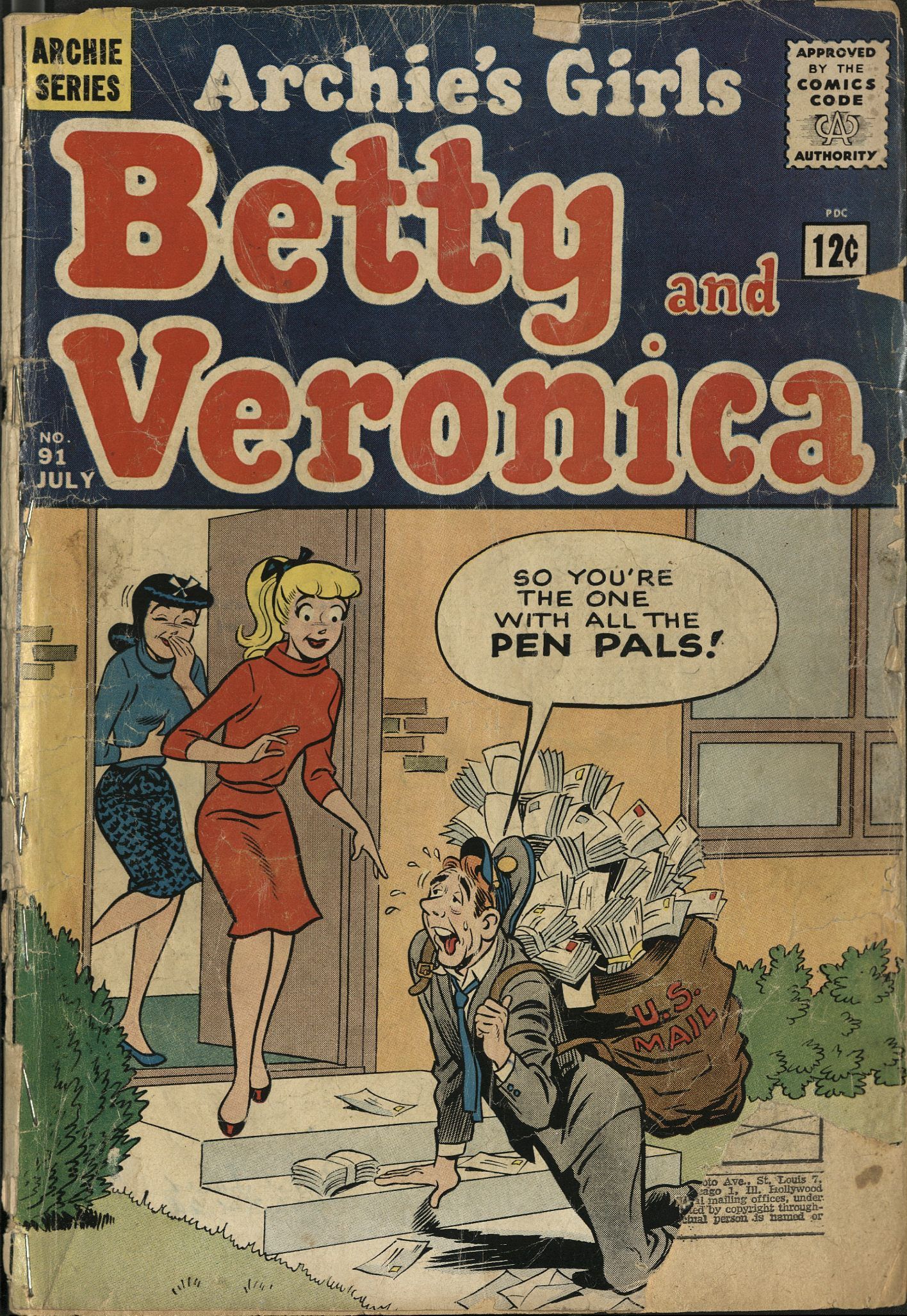

Mass Market Ads of a Bygone Era

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Kelli Brommel from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “Reading Culture History & Research in Media” (SLIS:5600:0001). Mass Market Ads of a Bygone Era By Kelli Brommel Amongst the wideContinue reading “Mass Market Ads of a Bygone Era”

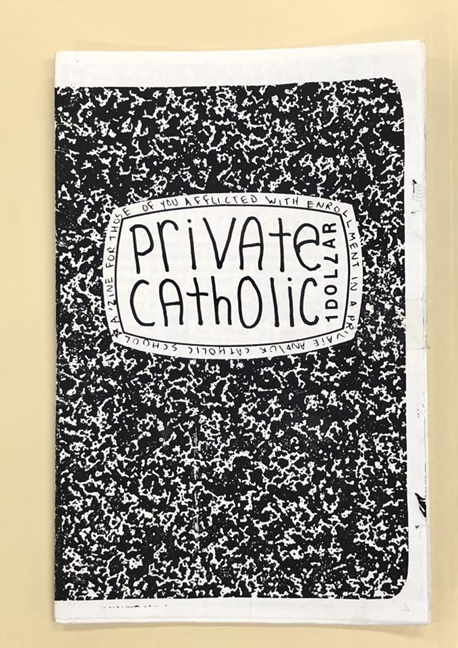

Private Catholic: Zines for Catholic School Kids

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Abbie Steuhm from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “Reading Culture History & Research in Media” (SLIS:5600:0001). Private Catholic: Zines for Catholic School Kids By Abbie Steuhm In the U.S.Continue reading “Private Catholic: Zines for Catholic School Kids”