We are pleased to welcome Rachel Poppen as our new collections archivist in Special Collections and Archives. Rachel joined the department in mid-July. Raised in Sibley, Iowa, Rachel received her Bachelor of Arts in English and Spanish from the University of Iowa. She then went on to receive her Master of Science in Information ScienceContinue reading “Welcome Rachel Poppen, new collections archivist”

Category Archives: University Archives

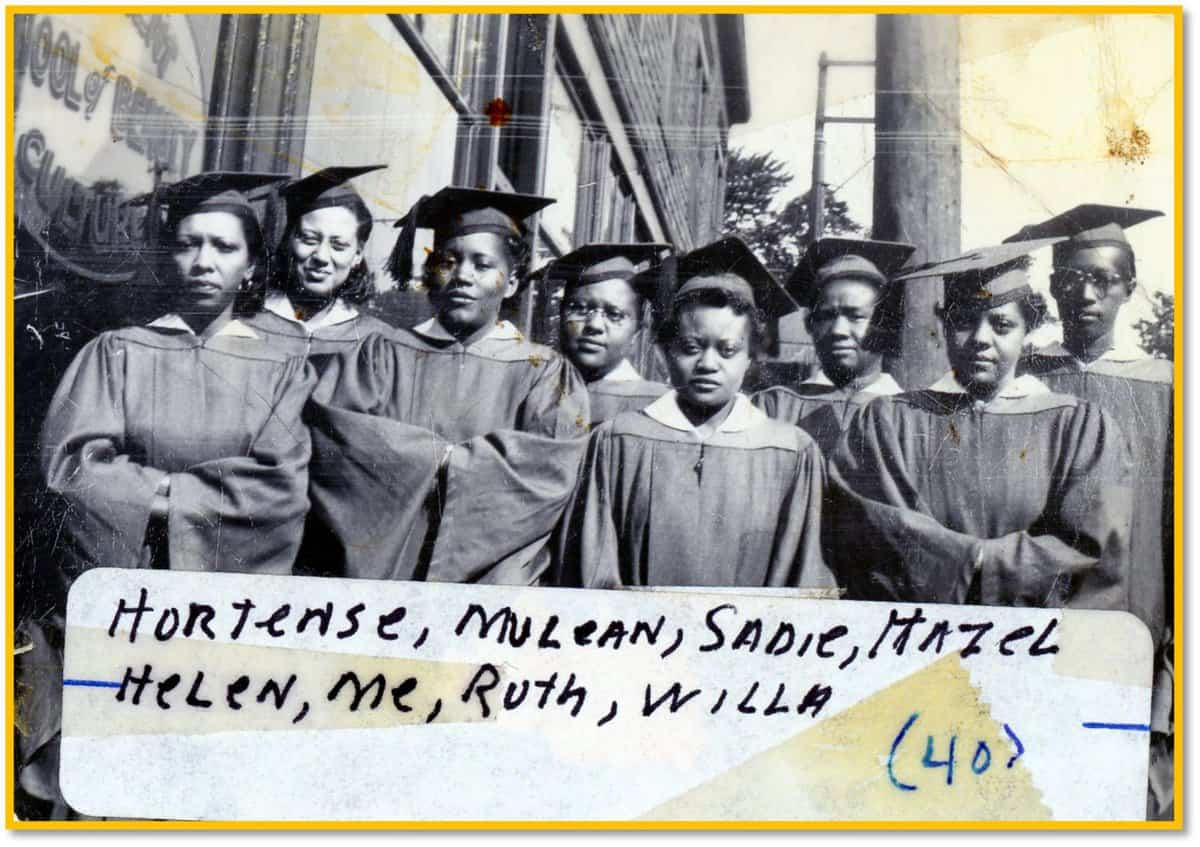

Professional Attention: The World of Labor

The following is written by Matrice Young, student life archivist and curator of Professional Attention: The World of Labor. Extra Extra! Read all about it!Jobs in America are varied and should be valued!Whether it be workin’ the field, fixing railroads,tightening locs or crocheting braids.Be it acrobatics, magic, music, or ballet.Librarians, nurses, comic artists, lecturers—No,All professionsContinue reading “Professional Attention: The World of Labor”

Welcome Matrice Young, new student life archivist

We are happy to welcome Matrice Young as our new student life archivist in Special Collections and Archives. Matrice joined the Libraries at the beginning of summer. Hailing from Chicago, Matrice received her BA in creative writing with minors in educational studies and Africana. She received her MA in Library and Information Science from UniversityContinue reading “Welcome Matrice Young, new student life archivist”

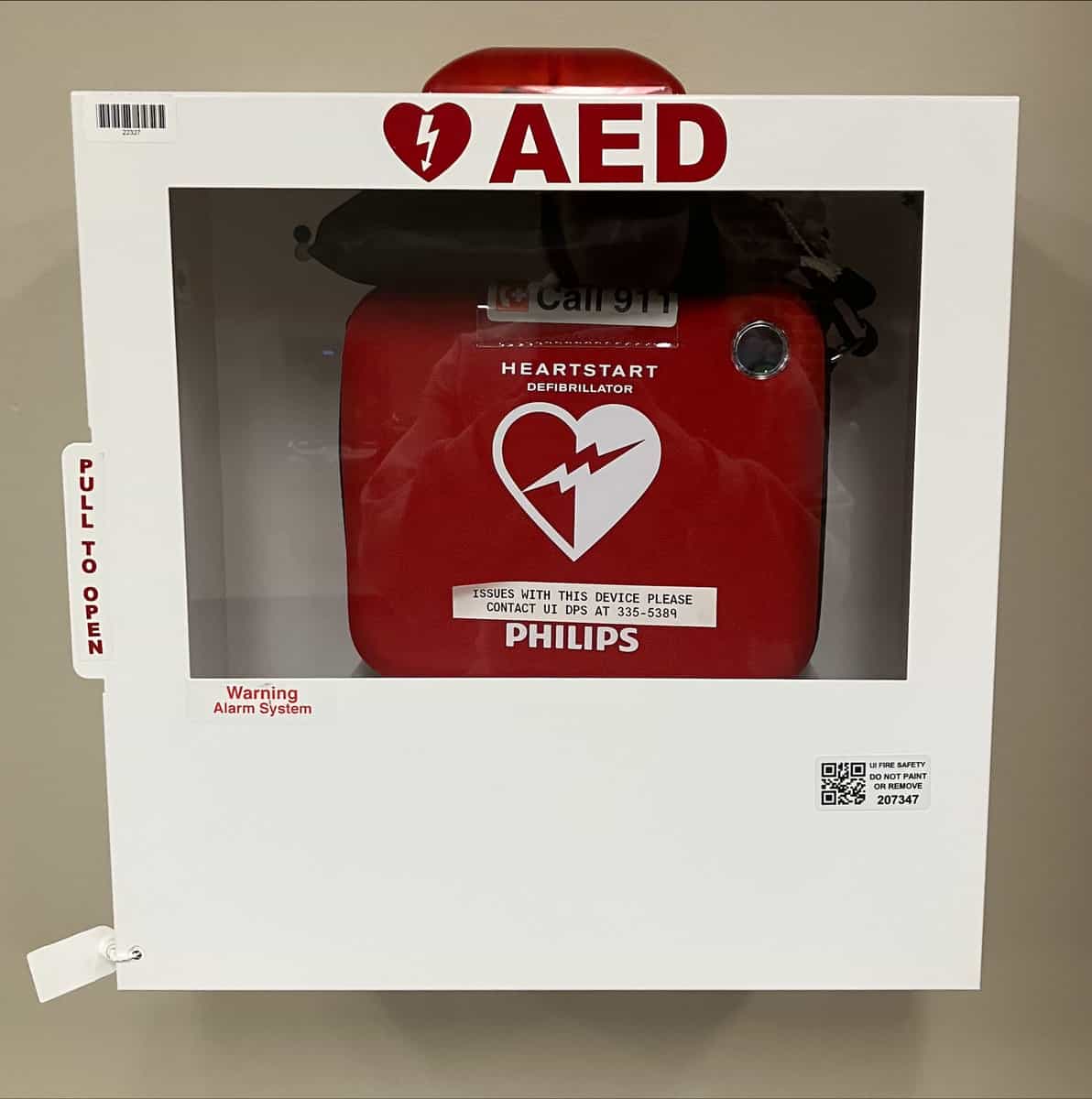

UIowa Hearts Richard Kerber

The following is written by graduate student and Special Collections student worker Emily Schartz To wrap up American Heart Health Month, we’re remembering University of Iowa professor, cardiologist, and researcher Richard Kerber (1939-2016). If you have noticed the white AED (Automated External Defibrillator) boxes around, you have seen Kerber’s long-lasting impact on our campus andContinue reading “UIowa Hearts Richard Kerber”

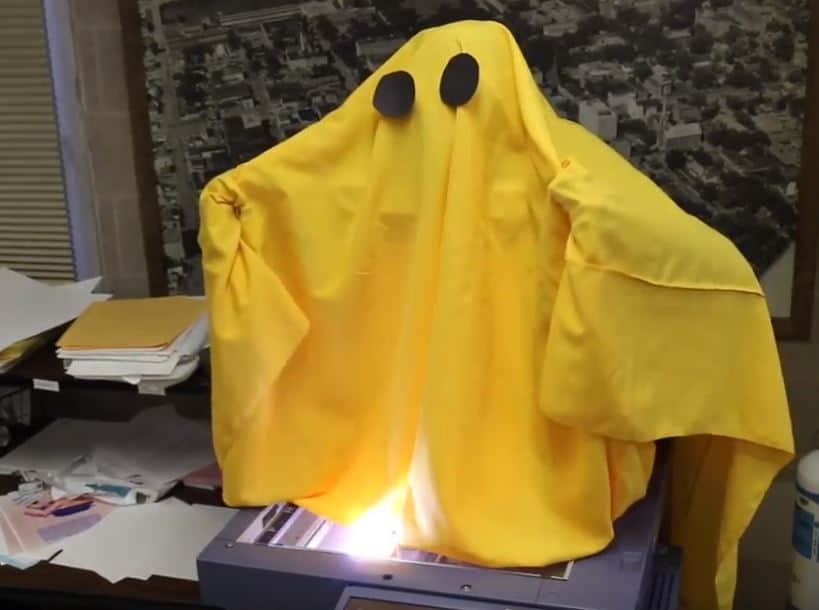

Collecting Your Ghost Stories

The following comes from university archivist Sarah Keen Have you heard footsteps where no corporeal being is walking? Have unexplainable events occurred in your building that have no humanly cause? Are there spaces on campus where the spirits of those who have walked this earth before us feel particularly present? If so, the University ArchivesContinue reading “Collecting Your Ghost Stories”

Welcome Sarah Keen, our new university archivist

We are pleased to welcome Sarah Keen as our new university archivist in Special Collections & Archives. Sarah joined the Libraries at the start of the fall semester. She comes to Iowa from upstate New York, where she served as Colgate University Libraries’ university archivist and head of Special Collections and University Archives. Previously, sheContinue reading “Welcome Sarah Keen, our new university archivist”

Art From Tragedy: Mauricio Lasansky’s The Nazi Drawings

The following is written by Academic Outreach Coordinator Kathryn Reuter Mauricio Lasanky was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1914 to Jewish immigrants from Lithuania. Lasansky showed artistic skill from a young age — printmaking was his preferred medium, a choice perhaps influenced by his father, who worked as a printer of banknote engravings. AfterContinue reading “Art From Tragedy: Mauricio Lasansky’s The Nazi Drawings”

Introducing SOAR: A Project for Preserving the Legacy of Student Organizations on Campus

The following is written by Community and Student Life Archivist Aiden Bettine The University Archives is embarking on a new, hands-on project to collect the history of student organizations on our campus, Student Organizations Archiving their Records or SOAR. The Purpose of SOAR is to ensure that the legacy of each student organization on theContinue reading “Introducing SOAR: A Project for Preserving the Legacy of Student Organizations on Campus”

University Archivist David McCartney is ready for the next chapter

He’s served as the University of Iowa’s institutional memory for the last 21 years, which includes writing the beloved Old Gold series. Now, University Archivist David McCartney is starting a new chapter. McCartney, who is retiring on March 1, has been dedicated to ensuring access to Iowa’s history and also highlighting voices that are underrepresentedContinue reading “University Archivist David McCartney is ready for the next chapter”

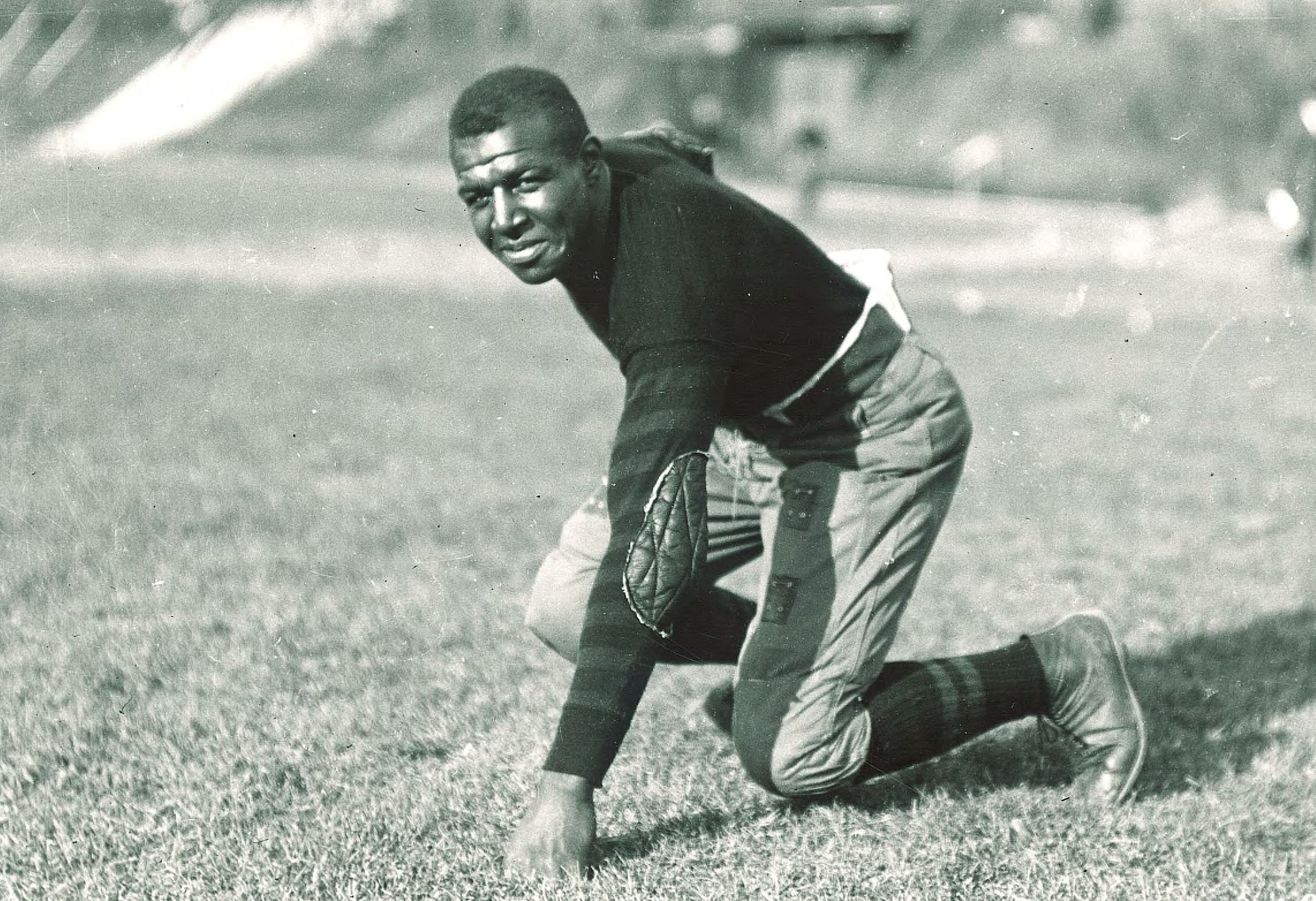

From Athlete to Judge: Famous UIowa Alum Duke Slater

The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant Matrice Young Frederick Wayman “Duke” Slater was born in 1898 in Normal, IL to George and Letha Slater. Slater’s first experience playing football came on the streets of the Southside of Chicago, playing pick-up games with the neighborhood kids. During their time playing, Slater discoveredContinue reading “From Athlete to Judge: Famous UIowa Alum Duke Slater”