“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Luke Allan from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “Reading Culture History & Research in Media” (SLIS:5600:0001).

Poems That Just Are

By Luke Allan

In a letter to a friend in the late 1950s, Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925–2006) admits to feeling that he must be “about the only contemporary writer who believes that the purpose of art is to—oh dearie me, I forget exactly what—let’s say: be beautiful.” Finlay is in his early thirties, living alone on a remote Scottish island, recovering from the collapse of his marriage, struggling with his mental health problems, and desperately poor. In 1959 he’ll move to Edinburgh, and from there to a dilapidated farmhouse in the Highlands. In the meantime he’ll meet his second wife, Sue, and in 1966 the young couple will move into a slightly less dilapidated farmhouse in the Pentland Hills, called Stonypath, and have their first child. For the next fifty years Ian and Sue will transform Stonypath, and the square acre of wilderness it sits on, nicknamed Little Sparta, into a unique “poem garden”, cultivated by the world’s first self-proclaimed “avant-gardeners”.

But let us take a step back. At some point in those years between moving to the city and leaving it again with Sue, Ian meets Paul Pond and Jessie McGuffie, and together they start a small poetry magazine, Poor. Old. Tired. Horse. The title is borrowed from a Robert Creeley poem, “Please”, and this borrowing itself hints at one of the motivations behind Ian’s interest in running a magazine: the wish to establish a community of likeminded poets and friends. In the mid-sixties Ian was diagnosed with agoraphobia, an event that, if nothing else, gave a name to the feelings of anxiety and alienation that had troubled him for many years, and which fenced him off from the world. Running a magazine would be, whatever else it would be, a way of having friendships in exile.

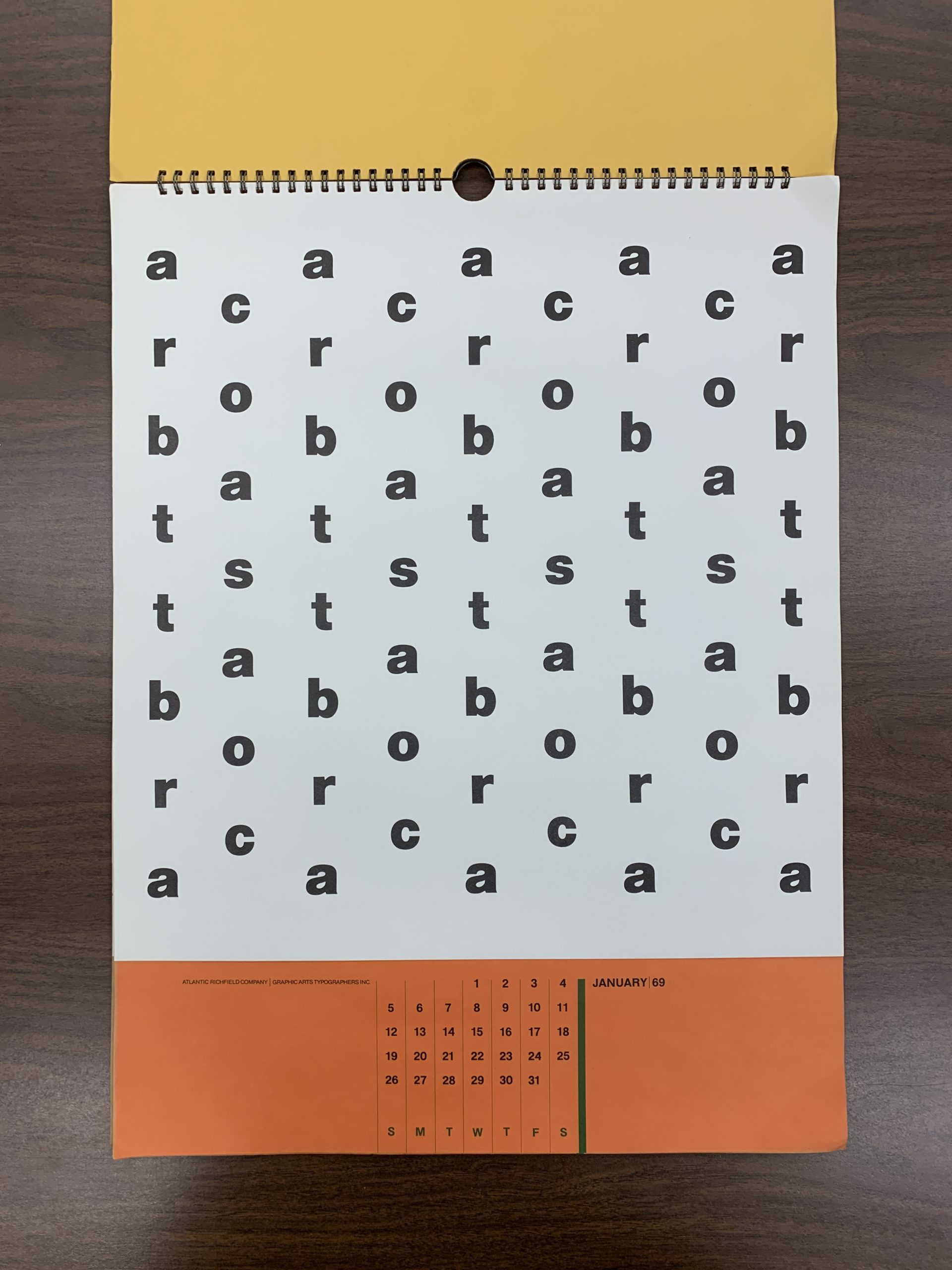

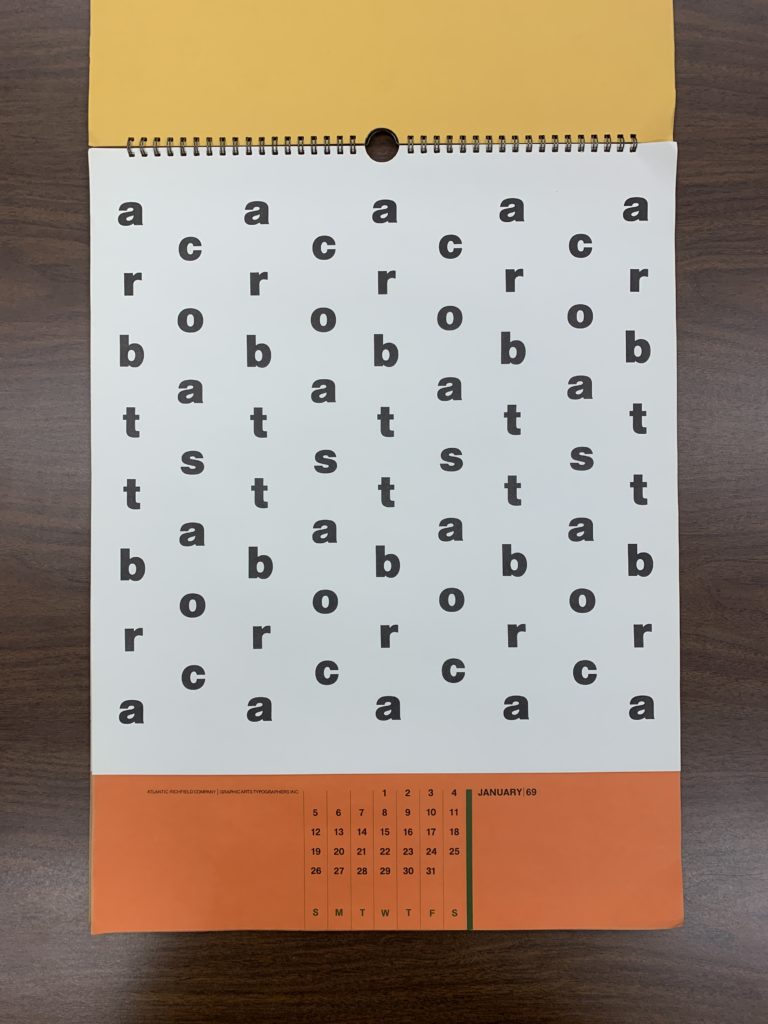

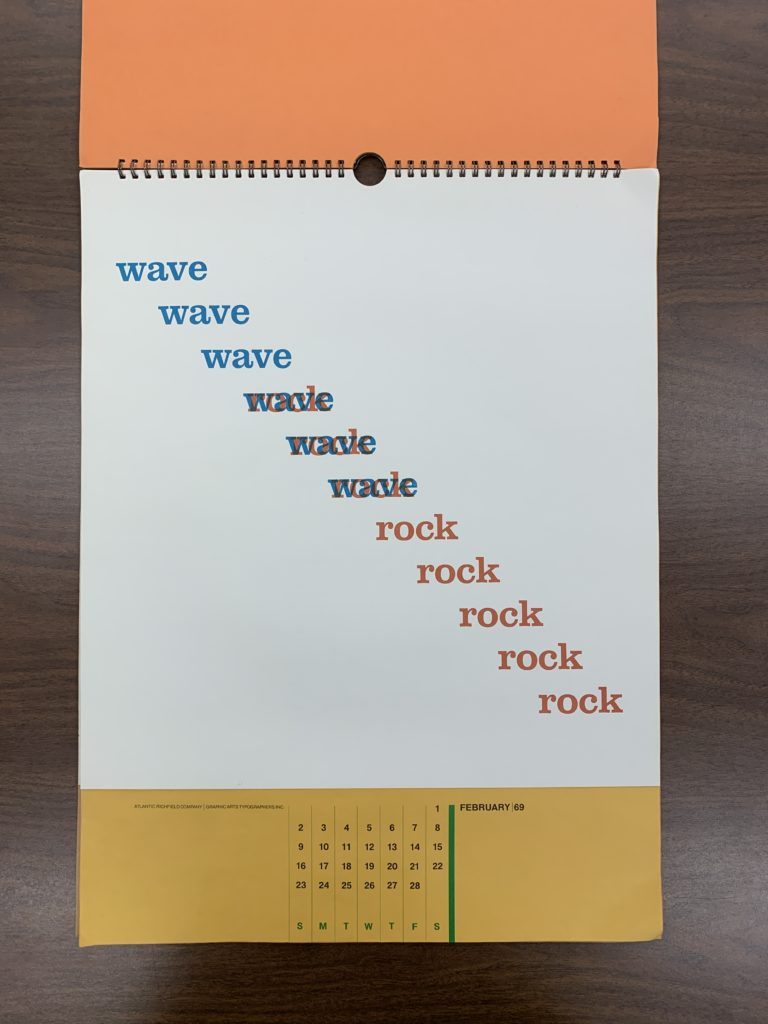

Editing POTH took Finlay on a long journey into the contemporary poetic avant-garde that would radically reorient his own writing. He already sensed that he no longer cared for poems that were merely “about” things, that he wanted instead poems “that just are” (letter to Gael Turnbull, 29 April 1963). But it was his encounter with the work of the Brazilian poet Augusto de Campos in winter 1962, while editing issue 6 of POTH, that lit the fuse for Finlay. De Campos’s poems were concretos—concrete. They demonstrated a way of thinking and writing that short-circuited traditional logical and grammatical structures. Feeling alienated from the “ordinary syntax” of “social reality”, as he put it in a letter to Jerome Rothenberg in 1963, Finlay found in concrete poetry a mode of thinking and writing that freed him from the grammar of a world he didn’t recognize as his own: concrete poetry became, for Finlay, “a model of order” within a world “full of doubt” (letter to Pierre Garnier, 17 September 1963). The encounter is crucial for Finlay. In POTH 8 (1963) Finlay publishes his first concrete poem, “Homage to Malevich”, and over the next five years he produces some of his greatest hits, including “acrobats” (1964) and “wave/rock” (1966). Much as Finlay used the magazine to establish a safe social space inside a larger, unstable world, so the concrete poem served as a microcosm of stillness and clarity within the disorder of modern life.

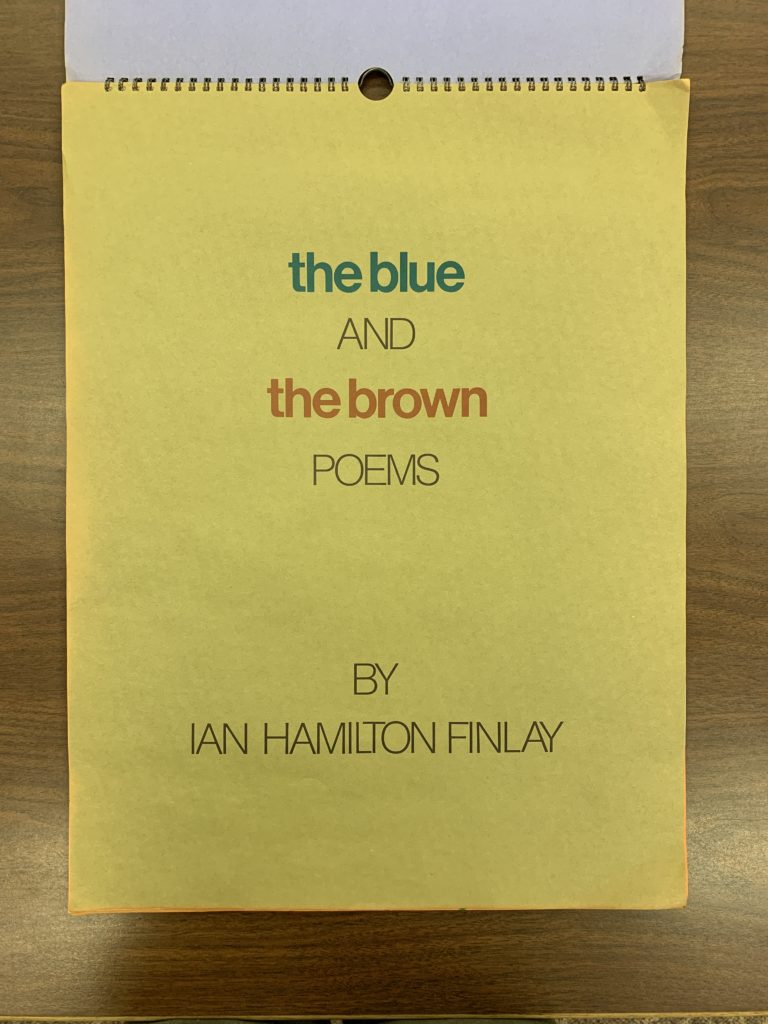

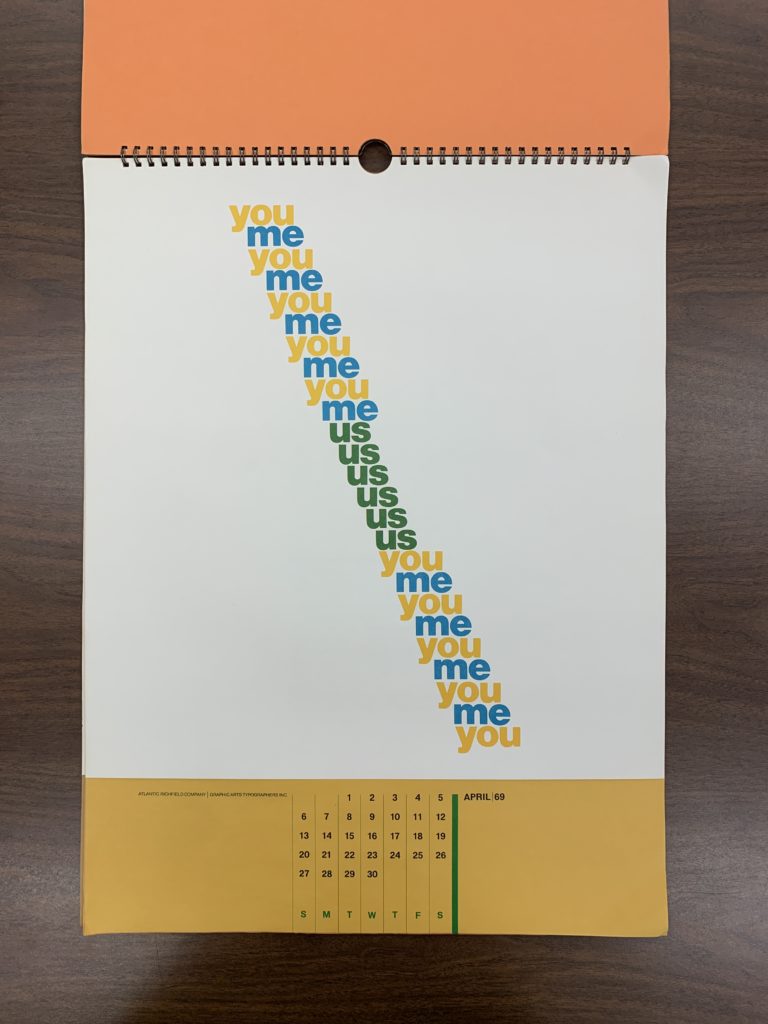

The poem-object shown in the images below is a calendar. Published in 1968, it collects twelve of Finlay’s early concrete poems, and is his first real encounter with a US readership. The calendar’s title, The Blue and the Brown Poems, is a reference to Wittgenstein’s Blue and Brown Books, transcriptions of lecture notes in which the philosopher first develops his destabilizing ideas about the relationship between words and meanings. The calendar is larger than you might think: at 20 inches tall, it’s probably too big for your fridge door or the space beside your desk. It asks, unusually for a calendar, for a more monumental setting, hung on a large wall like a framed painting or poster.

The calendar begins, also unusually, in September. This may be a reference to the calendar of the Roman Empire, in which case it’s an early example of Finlay’s interest in classical culture, a central theme of his later work. Each month features a concrete poem printed in color on white paper, accompanied by a short commentary by the critic Stephen Bann.

Finlay believed that concrete poems were for contemplating, so it followed that their ideal presentation was in a place where they could be readily contemplated. The calendar, like the wall or the garden, is a quintessentially Finlayian form. It is a way to turn the poem into something we can live around or within. Underpinning these considerations of form and space is a more fundamental belief in the relationship between poetry and ordinary experience: the calendar is a bridge between the heavens of literary culture and the ovens of real life in the home.

In ‘wave/rock’, the words “wave” and “rock” bear the colors of the sea and the land, and where the two words overlap there is a sonic collision that produces the “wrack”—seaweed washed up on the shore. Visually, the superimposed blue and brown letterforms give an impression of seaweed-covered rocks. A “wrack” is also a wrecked ship, the word suggesting sudden violent damage, and as these two words collide the wreckage miraculously takes on the form of a word for wreckage. In this sense the poem borrows the kind of forces found at sea as metaphors for the kinds of forces found in language.

Finlay started out as a writer of short stories and plays. In the middle of his life he found concrete poetry, and he set out on a journey into small-press publishing that would serve as his primary medium of friendship. In the final third of his life he realized the full potential of the concrete poem as a part of a landscape. Later, Finlay disassociated himself from concrete as a movement, because he felt that it did not share his views on the important function of tradition within the avant-garde. Today it is his garden domain, Little Sparta, for which he is best remembered, but at one level the garden is only the final manifestation of a poetic impulse to make enclosures that characterized Finlay’s oeuvre. The social enclosure of the magazine and the press, the aesthetic enclose of the concrete poem, and the physical and philosophical enclosure of the garden: these were ways of dealing with a sickness Finlay had diagnosed in the world and for which he spent his life discovering—oh dearie me, I forget exactly what—let’s say: beautiful cures.

* * *

When the University of Iowa acquired The Sackner Archive in 2019, work began to unpack and classify the 75,000 works of visual and concrete poetry that Ruth and Marvin Sackner had collected over the course of their lives. Ruth Sackner passed away in 2015, and Marvin Sackner joined her just a few weeks after the Archive’s inaugural exhibition, in September 2019. The work required to process the many books, prints, periodicals, letters, and objects that make up their enormous collection continues behind the scenes, and items from the archive are currently available to view by special request. Over time, the archive will be fully integrated into ArchivesSpace, but even now it is possible to browse the archive here.

Over the course of forty years Finlay published more than a thousand books, booklets, cards, prints and poem-objects, many through his publishing imprint Wild Hawthorn Press. It’s clear that Ruth and Marvin Sackner were enormous fans of Finlay’s work, because their collection contains several hundred of these publications. It’s a rich seam, and one that is still largely unexplored.

FURTHER READING

In print:

Yves Abrioux and Stephen Bann, Ian Hamilton Finlay: A Visual Primer (London: Reaktion Books, 1985; 2nd edition, revised and expanded, 1994)

A Model of Order: Selected Letters for Ian Hamilton Finlay, ed. Thomas A Clark (Glasgow: Wax366, 2009)

Patrick Eyres, “Gardens of Exile”, New Arcadian Journal 10 (1983)

Ian Hamilton Finlay: Selections, ed. Alec Finlay (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012)

Wood Notes Wild: Essays on the Poetry of Ian Hamilton Finlay, ed. Alec Finlay (Edinburgh: Polygon, 1995)

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Rapel: 10 Fauve and Suprematist Poems (Edinburgh: Wild Hawthorn Press, 1963)

John Dixon Hunt, Nature Over Again: The Garden Art of Ian Hamilton Finlay (London: Reaktion Books, 2008)

Caitlin Murray and Tim Johnson, eds., The Present Order: Writings on the Work of Ian Hamilton Finlay (Marfa, TX: Marfa Book Company, 2011)

Jessie Sheeler, Little Sparta: The Garden of Ian Hamilton Finlay, Photographs by Andrew Lawson (London: Frances Lincoln, 2003)

Online:

Carli Teproff, “A force on the Miami art scene, Ruth Sackner dies at 79”, Miami Herald, October 12, 2015. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/obituaries/article38777727.html

Andres Viglucci, “Marvin Sackner, a physician, inventor and renowned collector of word art, has died”, Miami Herald, September 30, 2020 https://www.miamiherald.com/article246121525.html?fbclid=IwAR1Tur1UbivcjHp3HaTx6AN2r8KJNNYXIcdFQc0meVeUXPieXJvQYhuUEJ8

Padded Cell Pictures, Concrete! (documentary about Marvin and Ruth Sackner) https://www.kaltura.com/index.php/extwidget/preview/partner_id/1004581/uiconf_id/15920232/entry_id/1_bv84gwjw/embed/dynamic?

Sackner Archive Live Exhibition.