The following is written by Academic Outreach Coordinator Kathryn Reuter On a college campus, chances are high that you will encounter at least one button during the course of your day. Pin back buttons – sometimes called “badges” – have long decorated the tote bags, backpacks, sweaters, and jackets of university students. Buttons proclaim allegianceContinue reading “Buttons, Buttons, Buttons!”

Tag Archives: Kathryn Reuter

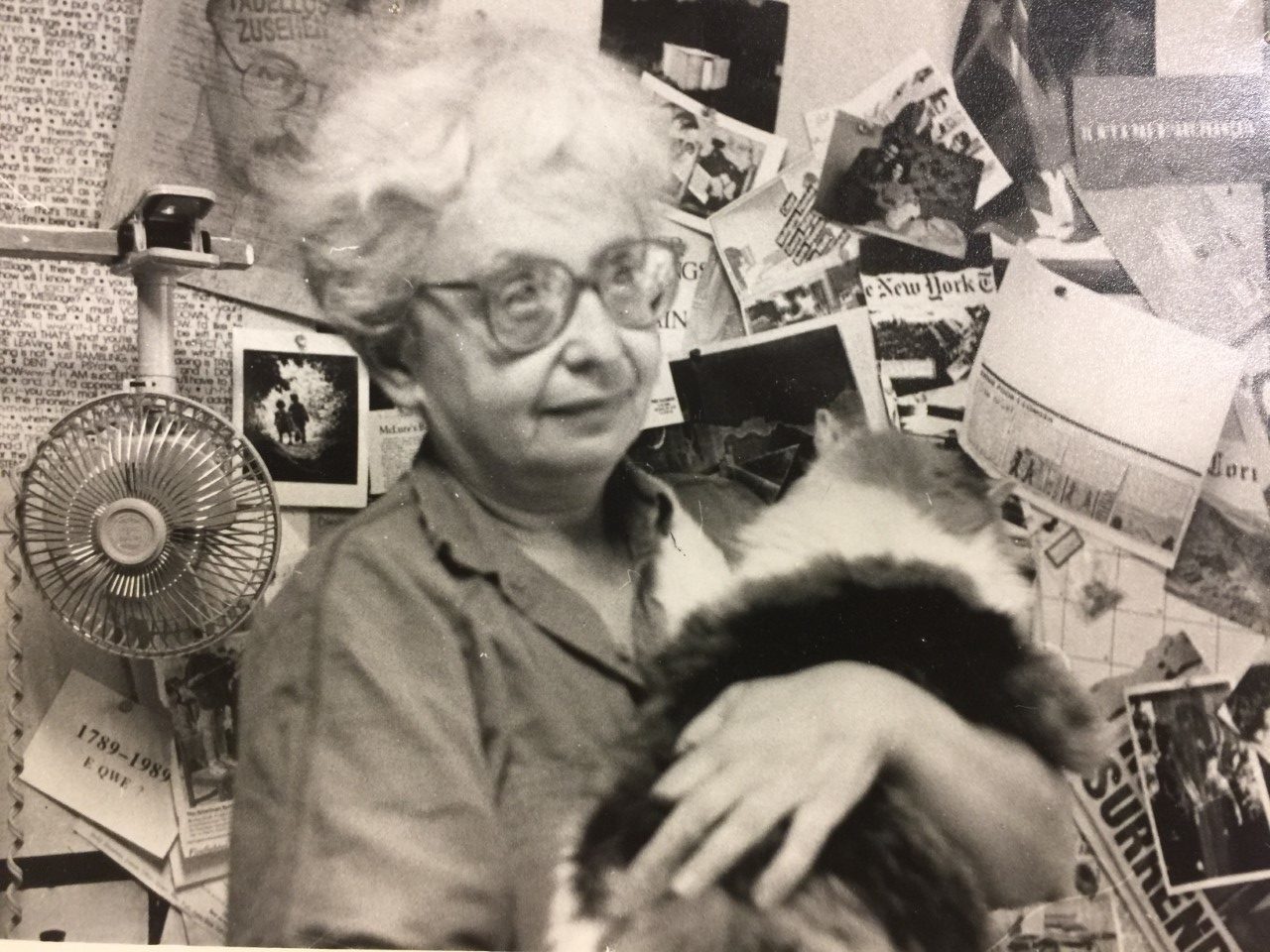

Happy Birthday Lil Picard!

The following is written by academic outreach coordinator Kathryn Reuter. On Tuesday, October 4th, 2022, join the Stanley Museum of Art & the University of Iowa Libraries’ Special Collections and Archives as they celebrate the 123rd birthday of artist Lil Picard! Crafts and cake will be available in the Stanley Museum lobby from 12-2pm, andContinue reading “Happy Birthday Lil Picard!”

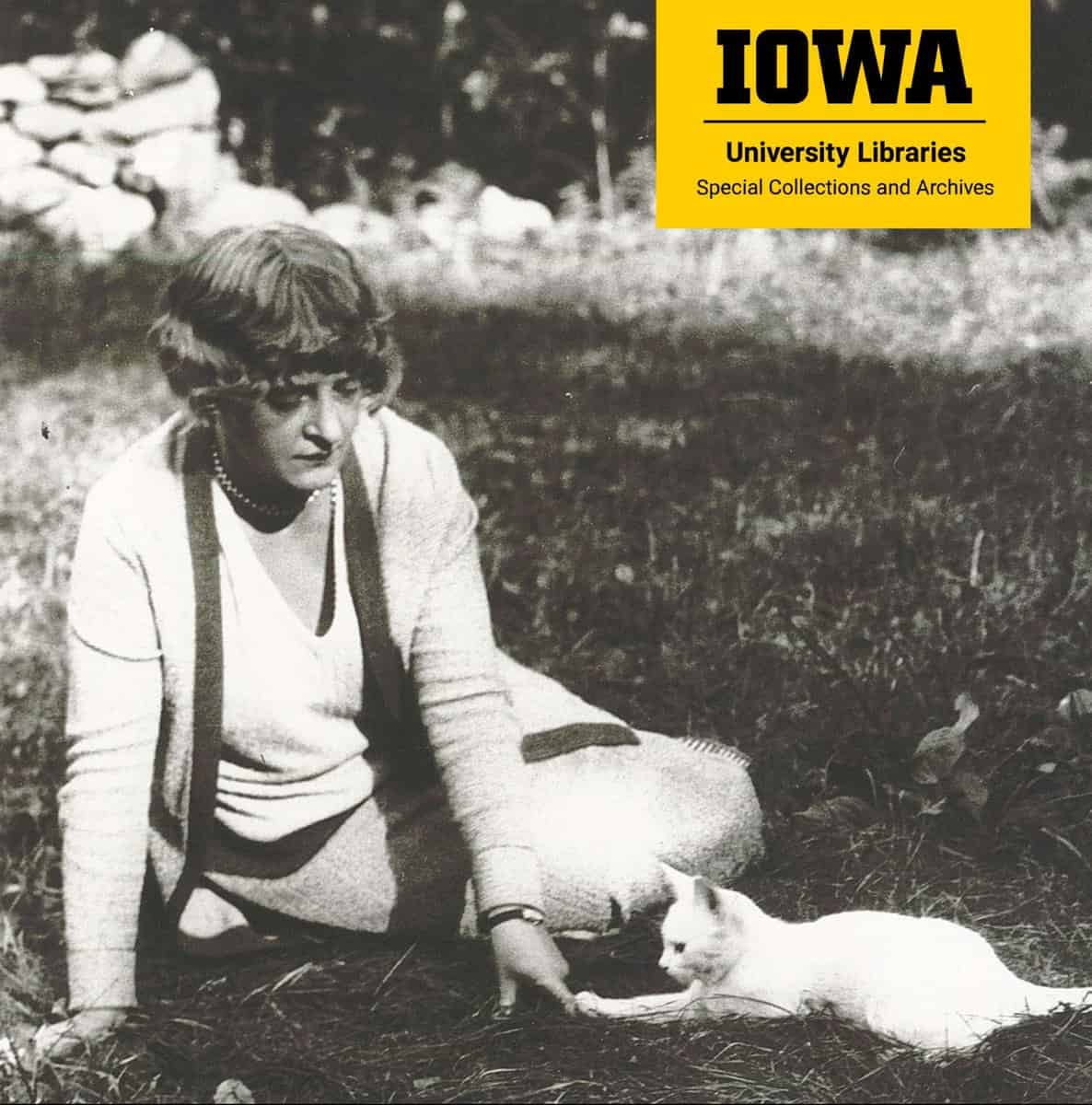

A Tale of Tails: Pets in the Archives

A new exhibit bound to make you feel warm and fuzzy is up in the Special Collections & Archives reading room. Curated by lead outreach and instruction librarian Elizabeth Riordan and academic outreach coordinator Kathryn Reuter, the exhibit A Tale of Tails: Pets in the Archives explores the pets found in Special Collections & Archives,Continue reading “A Tale of Tails: Pets in the Archives”

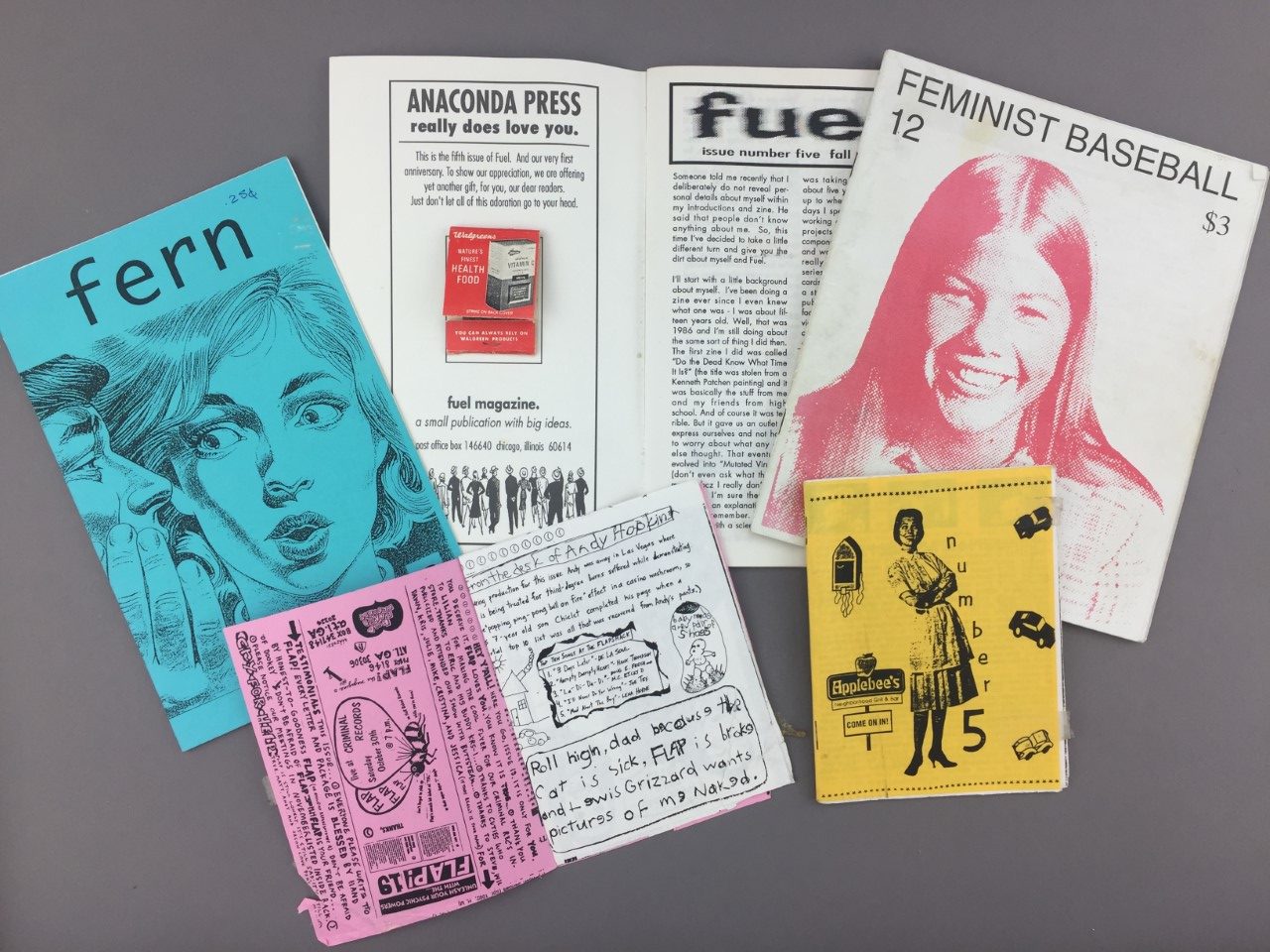

Telling Their Stories: LGBTQ+ Zine History

The following is written by Academic Outreach Coordinator Kathryn Reuter In honor of Pride month, we are highlighting some queer zines in our collections. A zine is a hand-made and self-published pamphlet that can contain writings, collages, comics, illustrations, and other artwork. Zines are made in a variety of styles and cover endless types ofContinue reading “Telling Their Stories: LGBTQ+ Zine History”

Art From Tragedy: Mauricio Lasansky’s The Nazi Drawings

The following is written by Academic Outreach Coordinator Kathryn Reuter Mauricio Lasanky was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1914 to Jewish immigrants from Lithuania. Lasansky showed artistic skill from a young age — printmaking was his preferred medium, a choice perhaps influenced by his father, who worked as a printer of banknote engravings. AfterContinue reading “Art From Tragedy: Mauricio Lasansky’s The Nazi Drawings”

Louise Neaderland and The International Society of Copier Artists

The following is written by Kathryn Reuter, Academic Outreach Coordinator for Special Collections & Archives and for Stanley Museum of Art In 1938, Chester Carlson invented the process of electrophotographic printing. Later rebranded as xerography, this process is what fuels photocopy machines around the world. Carlson’s invention forever changed the nature of office work andContinue reading “Louise Neaderland and The International Society of Copier Artists”

Introducing Kathryn Reuter, Academic Outreach Coordinator

Special Collections & Archives is excited to welcome Kathryn Reuter to the team as our new Academic Outreach Coordinator. As Academic Outreach Coordinator, Kathryn will be working with both the UI Libraries and Stanley Museum of Art to increase visibility and usability of our deep and culturally diverse collections of art and visual materials. KathrynContinue reading “Introducing Kathryn Reuter, Academic Outreach Coordinator”