The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant, Rachel Miller-Haughton

This article will use the words ‘Native American’ and ‘Indigenous’ to refer to the people and cuisines mentioned. Other words, some of which are considered offensive or slurs, are used in these books, and are only mentioned if necessary, in direct quotes.

November is National Native American Heritage Month, and at Special Collections & Archives we would like to highlight the books within the Szathmary Culinary Manuscripts and Cookbooks Collection that feature Indigenous foods. While not a huge swath of the collection, there are a few materials that range from mid-1900s white-narrated accounts of stereotypes about Indigenous people interspersed with recipes for broadly named “typical foods;” to contemporary cookbooks by Indigenous chefs like The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen (2017).

Thanksgiving is a time that can mean vastly different things to different people. Stories are written and rewritten about the ways in which white Europeans interacted with the Native communities on whose lands they settled. For Indigenous activists, this can be a painful day: in 2017, Karlos Baca, a chef who is Diné, Tewa and Nuche, said he had a tradition of fasting on Thanksgiving. Sean Sherman, a chef who is Oglala Lakota, reminds us that when we forget the impact of Indigenous cuisines on the holiday, we are forgetting the people who shaped American food and culture. “It’s the one time of the year that people, whether they know it or not, are largely making indigenous-based foods […] There’s turkey, squash, cranberries — and all these pieces that represent indigenous America” (from the article “‘This is not a trend’: Native American chefs resist the ‘Columbusing’ of indigenous foods”).

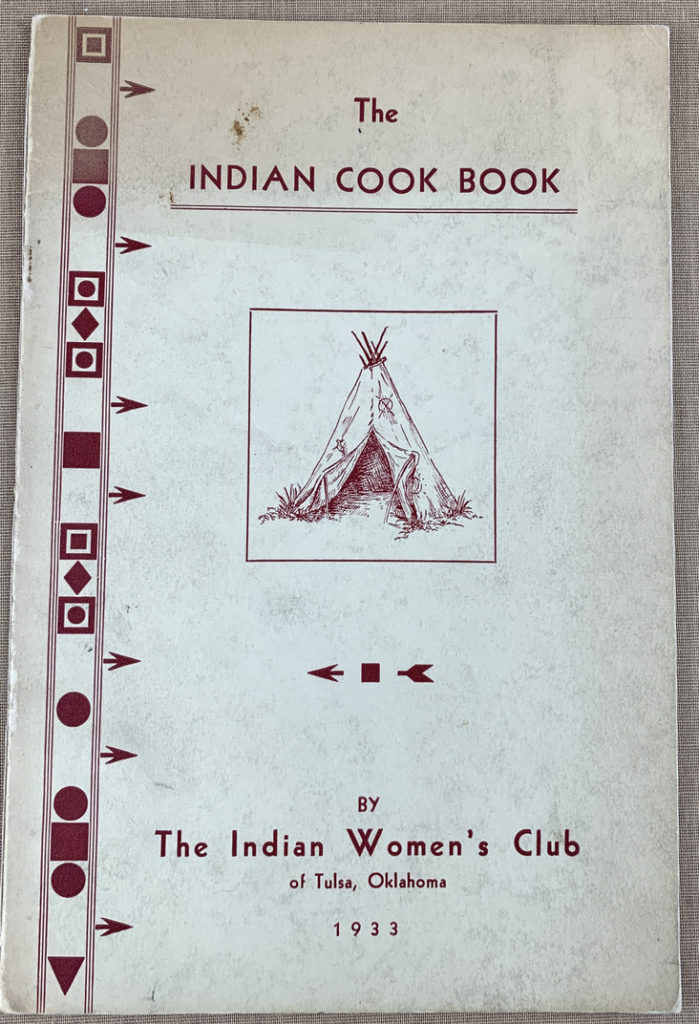

Remembering contributions of some Native Americans to the survival of others’ white ancestors is one step. A few books in the Szathmary Collection highlight the past. One is The Indian Cook Book by The Indian Women’s Club of Tulsa, Oklahoma, written in 1933.

It is a compilation of different women’s short recipes, listed above their name and tribe. The foreword reads, “We are sending forth this little pamphlet to you and the public as a souvenir of other days among the early Indian homekeepers, hoping it will prove to be not only a useful, but one of your cherished possessions. Sincerely, Lilah D. Lindsey, President, Creek and Cherokee.”

A further step to take is to acknowledge that Native American people are very much a part of the fabric of contemporary life, not historic figures that just occupied the past. Indian Recipes was compiled by the staff of United Tribes Employment Training Center, North Dakota in 1977.

A small orange booklet with illustrations and recipes, there is little context or history given. The last page says, “United Tribes Employment Training Center (UTETC) is a non-profit vocational-educational training center operated by the Indian people of North Dakota for Indians, regardless of educational background. The basic objective of the Center is to educate Indian people of low socio-economic backgrounds so that they are capable of living in today’s changing society.” Made by people in North Dakota and intended to be distributed to any Indigenous community member who needed recipes, this cookbook created both connections to heritage foods and everyday recipes for the household.

Some cookbooks come from non-Indigenous authors. The Art of American Indian Cooking by Yeffe Kimball and Jean Anderson (1965) is one such book. It’s intended to give a sampling of many regions, from many different Indigenous nations. The foreword and introduction to this volume start off innocuously, noting that “our debt to the American Indian is much greater than we had supposed at first.” It goes on to describe origins of Indigenous foods, their origins of cultivation, and the importance of corn in many Indigenous communities across the continent. However, it veers into whitewashing as author Yeffe Kimball then paints a simple and tidy picture of the first Thanksgiving. Interestingly, Kimball (born Effie Violetta Goodman) was born to white parents and self-identified as an Osage Native American, though she was not.

As with any archive, a blend of the old and new paints a timeline of the ways in which a marginalized and underrepresented community has appeared, portrayed first by others and later by members of those communities. The power to tell your own story is incredibly important.

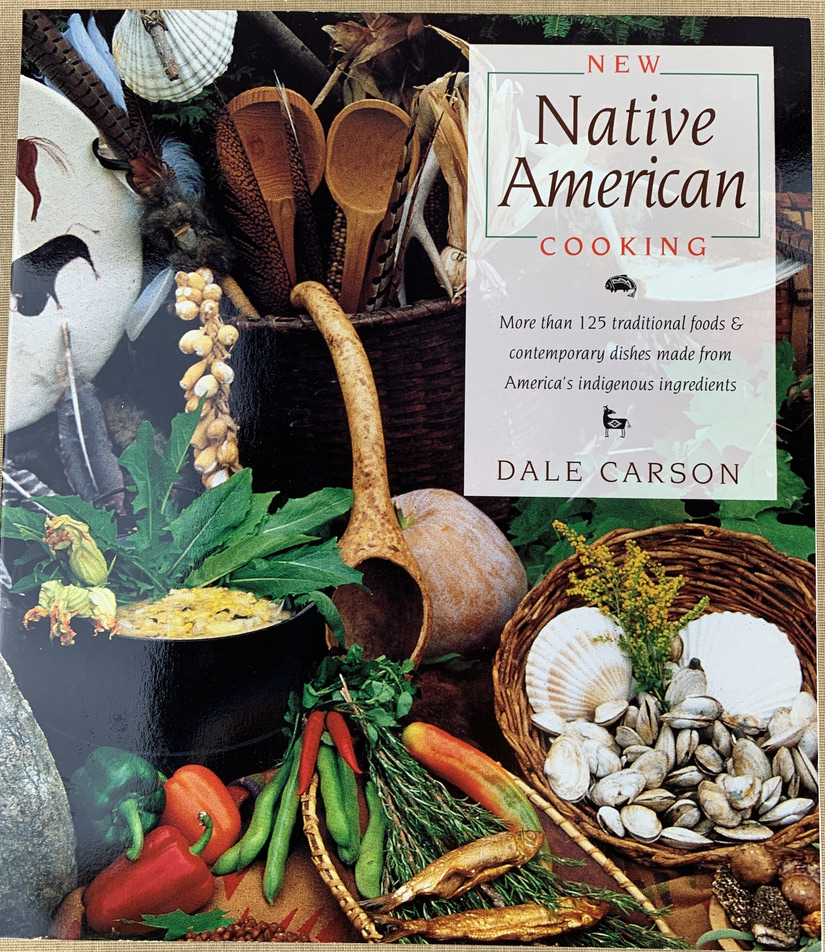

Some of the most recent cookbooks are by individual chefs who have compiled recipes they have perfected. One is

Dale Carson’s (Abenaki) 1996 book, New Native American Cooking: More than 125 traditional foods & contemporary dishes made from America’s indigenous ingredients. Carson says she’s “included recipes that represent the foodstuff and culinary traditions of all the North American culture groups. You’ll notice many Woodland dishes from both the Easter and Great Lakes regions. I’ve also adapted a number of Southeastern, Plains, Western and Northwestern dishes for this collection […] like other Americans, Native peoples shop at supermarkets, buy butcher shop meats, and stock canned and frozen fruits and vegetables on the pantry shelves of modern kitchens […] this book is not intended as a history of Native foods, nor is it a collection of purely traditional recipes. In many ways, I consider it a bridge, a means of reintroducing Native American food and culinary traditions into mainstream kitchens.” Carson is still active in sharing Abenaki and other Indigenous food through her writing.

A project to “re-identify North American Cuisine” is the work of chef Sean Sherman (Oglala Lakota) and his partner Dana Thompson. Sherman’s The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen (written with Beth Dooley, 2017) is the most recent Indigenous cookbook in Special Collections. “Sherman dispels outdated notions of Native American fare—no fry bread or Indian tacos here—and uses no European staples such as wheat flour, dairy products, sugar, and domestic pork and beef […] The Sioux Chef’s Indigenous Kitchen is a rich education in and a delectable introduction to modern indigenous cuisine of the Dakota and Minnesota territories” (Introduction).

Whether you have never considered the roots of Thanksgiving before, or whether you have dedicated your life to the work of decolonizing, we hope you can appreciate the heritage of the foods you consume on November 25th this year. We are thankful to house Native American recipes and histories here at the University of Iowa, which is located on the homelands of many Indigenous nations (please visit the UI Indigenous Land Acknowledgement). We hope to build a stronger relationship with Indigenous students, faculty, and staff, so that their voices will be better represented in the archives.

Resources:

Iowa Meskwaki Food Sovereignty program

UI Native American Student Association

UI Indigenous Land Acknowledgement

I-Collective: “An autonomous group of Indigenous chefs, activists, herbalists, seed, and knowledge keepers, the I-Collective strives to open a dialogue and create a new narrative that highlights not only historical Indigenous contributions, but also promotes our community’s resilience and innovations in gastronomy, agriculture, the arts, and society at large.”

North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems (NATIFS), Sean Sherman and Dana Thompson’s