“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Allison Clark from Dr. Beth Yale’s class Transition from Manuscript to Print (HIST: 4920:0001).

Insights Gained Regarding Illustrations in Books of Hours

By Allison Clark

Entering Special Collections for the first time can be, to put it plainly, intimidating. That is to say that no one wants to be the person who accidentally tears a page, leaves a smudge, or, heaven forbid, forgets to wash their hands. But, after a couple visits, familiarity starts to sink in. Suddenly, you instinctively go to wash your hands before handling a book and you know where to turn the page to avoid damage (spoiler: in the middle, not the corner). Once you have moved past the initial feelings of intimidation and take the opportunity to study a book intimately, Special Collections & Archives is a fantastic resource for learning on campus, as I have come to learn. The following are the results from my time spent in Special Collections & Archives, specifically my encounters with three books: Book of Hours of Martine Sesander (xMMs.Bo10), Book of Hours (xMMs.Bo5), and Ces Presentes Heueres (BX2080.A2 1502). My research focuses on the insights that each of these books offers into different practices and aspects relating to illustrations in books of hours.

Books of hours were Christian prayer books that allowed lay people to participate in the liturgy, and they evolved from the books that clergy, monks, and nuns would use for reciting prayers throughout the day. They were extremely popular in their day and have been described as a “best-seller in medieval and early modern Europe” (Reinburg). Initially, they were “given as gifts to the noble patrons of monasteries and convents” (Reinburg). Later on, once lay people began to have more control over their circulation, books of hours began to be commissioned by the wealthy. As usership increased, they were essentially divided into two groups: the luxurious, heavily illuminated manuscripts and the less decorated and thoughtfully designed manuscripts. Then, once the technology of printing was introduced, books of hours became even more accessible, though the appearance of them eventually changed, including the illustrations. The illustrations in books of hours are a particularly integral part of these devotional books. Illustrations served three primary functions. First, they were decorative and “added to the book’s value and splendor” (Reinburg). They also added structure and aided those who were illiterate, guiding the reader through the book. Finally, they were devotional and “offered a focus for prayer and meditation” (Reinburg). Essentially, illustrations would have functioned as “painted prayers” (University of Glasgow Special Collections). Since illustrations in books of hours are so important, there is a lot to learn surrounding different aspects and practices associated with them, as is evidenced by Book of Hours of Martine Sesander, Book of Hours, and Ces Presentes Heueres.

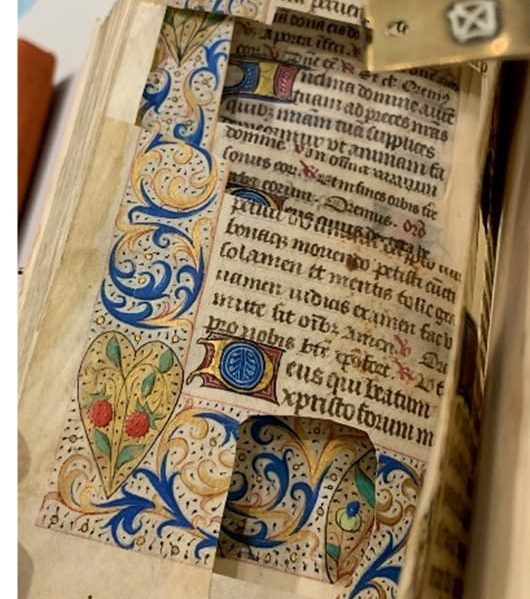

Book of Hours of Martine Sesander (xMMs.Bo10)

Book of Hours of Martine Sesander (xMMs.Bo10) is a small manuscript from 1465 written in Latin. According to the University of Iowa Libraries catalog, this book likely came from Belgium, a likelihood based on the saints mentioned in the book. There is a gold inscription in the back of the book that identifies an early user as Martine Sesander, thus the title. It has striking dark green cover with gold details and is highly illustrated with features illuminated throughout the book, floral decorations in the margins, and six full-page miniatures. Book of Hours of Martine Sesander (xMMs.Bo10) stands out because there is evidence of the physical ritual of kissing and rubbing images in this book of hours. What is particularly interesting about books of hours, is the personal relationship that users had with these books, and this relationship is seen in the act of rubbing and kissing devotional manuscripts, which was a common practice. Christians “kissed images in their prayer books, just as the priest would have kissed the missal during Mass” (Rudy). Furthermore, readers were selective about which images they would rub or kiss. Looking closely at the illustration of Mary and Jesus, there are signs of wear over Jesus’s left shoulder where the paint has been rubbed away. This suggests one user of this book was drawn to this illustration, which begs the question of why this one? When looking at signs of wear, the illustrations in books of hours, like this one, offer a unique look into the religious lives and devotional practices of their owners.

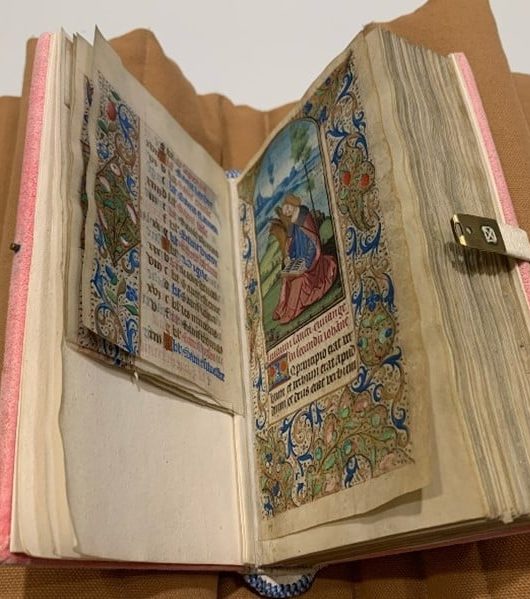

Book of Hours (xMMs.Bo5)

This book of hours is hard to miss with its bright pink leather cover and white leather clasp, which was rebound in 1998 by Pam Spitzmeuller. It is a French parchment manuscript written in Latin. According to the library catalog, Book of Hours (xMMs.Bo5) was made in the second half of the fifteenth century in France, determined by the inclusion of the Paris calendar. This book has vibrant capitals in gold and blue and decoration in the margins, with illumination throughout. The illustrations in this book, or rather lack thereof, offer insight into the practice of cutting up manuscripts for their decorations. Sadly, this book only has one full page illustration of Mary remains. The floral designs in the margins have also been mutilated. Surprisingly, or perhaps unsurprisingly, the nature of this manuscript is not uncommon, according to librarian Christopher de Hamel. It seems there are a variety of reasons for cutting up manuscripts. For instance, there are stories of libraries giving out clippings from pages as gifts to visitors. There are also cases of children cutting out initials and using them to practice spelling out their names, which is almost amusing, save the destruction of artwork. In addition, manuscript owners would cut up their own books to display them in a portfolio or album, like a scrapbook. Of course, clippings are also sold, and sellers would create albums of manuscript clippings for buyers. These clippings would sell for such high prices that it would have been tempting not to partake in this destruction.

“The deliberate destruction of any unique work of art can only be regarded as unforgivable vandalism.”

-Christopher de Hamel, July 1995

The practice of selling leaves or clippings out of manuscripts continues, although collectors rarely admit to cutting up their own manuscripts and pass the blame onto previous owners (de Hamel). To play devil’s advocate, there are reasons that this practice could potentially be justified. Clippings and leaves allow for manuscripts to be more accessible to more people, since it is easier for libraries and museums to purchase single sheets as opposed to an entire book. They also are easier to store, conserve, and exhibit. And, of course, there is the economic argument, as clippings do sell well. This being said, the practice does remain controversial, and some, such as de Hamel, cannot excuse it. Of course, it should be noted that the manuscript was already in this condition when purchased by the University of Iowa. The damage has been done, but even this damage provides information on book users and the practice of cutting up manuscripts.

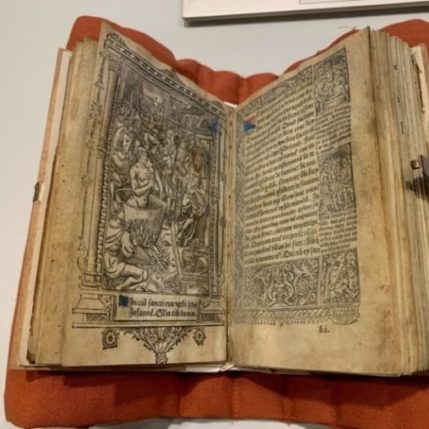

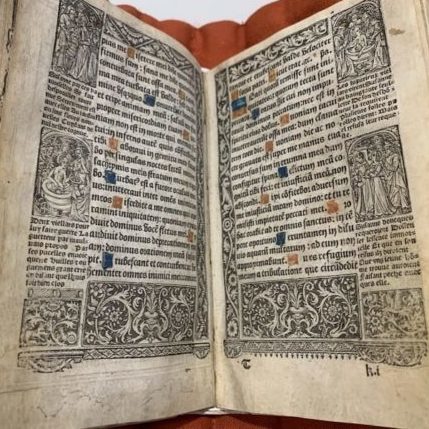

Ces Presentes Heures (BX2080.A2 1502)

Ces Presentes Heures (BX2080.A2 1502) is a French book of hours written in Latin with four leaves of French prayers at the end. It has a wooden cover with a leather clasp, and the initials have been stylized in blue and red paint. Ces Presentes Heures (BX2080.A2 1502) is different than the other books of hours discussed above because it is a printed book and not a handwritten manuscript. However, Ces Presentes Heures (BX2080.A2 1502) is printed on parchment, which indicates an overlap of manuscript and printing practices. Therefore, this book offers insight into the effect that the printing industry had on books of hours.

The new technology of printing did not eliminate manuscripts. While the invention of print did make books of hours more accessible to laypeople, manuscript books of hours continued to be produced and remained popular well after the invention of printing (Reinburg). In addition, there is evidence of scribes copying printed books into manuscripts, showing how scribal work continued to be valued well into the era of printing (Drimmer). Initially, printed books of hours were even created to look like manuscripts, as we can see with the blue and red lettering found within the book.

Eventually, they began to take their own form and started to feature heavily illustrated borders and many full-page illustrations (Reinburg). This is seen in Ces Presentes Heures (BX2080.A2 1502), which is riddled with illustrations. Nearly every page has pictures in the margins as well as many full-page illustrations. It has been said, however, that “as a work of art, the book of hours lost some luster by moving into print” (Reinburg). It could also be suggested that perhaps the quantity of the images was to make up for the fact that they were printed, instead of hand illustrated, or to show off the new technology (Riordan). However, there is no doubt that the illustrations in Ces Presentes Heures (BX2080.A2 1502) are extremely detailed, which is arguably just as, if not more, impressive as the paintings in the manuscript copies.

One particularly interesting portion was a series of pages which showed the character Death, depicted as a skeleton, coming to take away all different kinds of people, including powerful figures like a king and the Pope. One cannot help but wonder (how readers would feel seeing these images of Death escorting representations of themselves to the next life. Due to the fact that this book is printed on parchment and includes hand-drawn elements on the lettering, Ces Presentes Heures (BX2080.A2 1502) acts as an example for how printing did not completely replace the traditions of manuscript books.

These three books, each reveal different aspects of illustrations in books of hours. The worn illustrations of Book of Hours of Martine Sesander (xMMs. Bo10) disclose a glimpse into the religious life and habits of its reader and demonstrate the personal relationship owners had with their books of hours. The mutilated pages of Book of Hours (xMMs. Bo5) make plain the evolving relationship with these books and the ever so controversial practice of cutting up manuscripts. And, finally, the detailed illustrations and parchment pages of Ces Presentes Heures (BX2080.A2 1502) offer insight into the transition and overlap between manuscript and print. Each of these books offers a unique look into the past and how illustrations in books of hours were used, abused, and changed overtime.

Bibliography

de Hamel, Christopher. “Cutting Up Manuscripts for Pleasure and Profit.” Rare Book School Lectures. Lecture, July 1995.

Drimmer, Sonja. “Introduction: The Manuscript Copy and the Printed Original in the Digital Present.” Digital Philology: A Journal of Medieval Cultures 9, no. 2 (2020).

“Fifteenth Century Book of Hours.” University of Glasgow Special Collections, December 2006. <https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/library/files/special/exhibns/month/dec2006.html>

Reinburg, V. (2012). French books of hours : Making an archive of prayer, c.1400–1600. ProQuest Ebook Central <https://ebookcentral.proquest.com>

Riordan, Elizabeth. Personal communication, University of Iowa Special Collections & Archives, March 30,2021.

Rudy, Kathryn M. “Kissing Images, Unfurling Rolls, Measuring Wounds, Sewing Badges and Carrying Talismans: Considering Some Harley Manuscripts Through the Physical Rituals

They Reveal.” British Library, 2011.

University of Iowa Library Catalog, “Book of Hours of Martine Sesander (Use of Rome)”.

University of Iowa Library Catalog, Catholic Church. (1499). Ces presentes heures a lusaig. de Tou : au long sans requerir.

University of Iowa Library Catalog, Spitzmueller, Pamela J., Ficke, Charles August, & University of Iowa. Libraries. Special Collections Department. (n.d.). Book of Hours, second half of the 15th century.

Wijsman, Hanno. Books in Transition at the Time of Philip the Fair. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2010.

“Willem Vrelant (Getty Museum).” The J. Paul Getty in Los Angeles.