The following is written by Academic Outreach Coordinator Kathryn Reuter

Mauricio Lasanky was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1914 to Jewish immigrants from Lithuania. Lasansky showed artistic skill from a young age — printmaking was his preferred medium, a choice perhaps influenced by his father, who worked as a printer of banknote engravings. After completing high school, Lasansky studied printmaking at the Superior School of Fine Arts and after just three years, was named director of the Free School of Fine Arts in Cordoba, Argentina. His work caught the attention of Henry Francis Taylor, who was then director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Taylor recommended Lasansky for a Guggenheim Fellowship, a distinction Lasansky was awarded in 1943—with a renewal in 1944. This fellowship allowed Lasansky to travel to New York City, where he worked at the famed printmaking workshop Atelier 17 and, over the course of two years, reportedly studied every. single. print. of the old masters in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Drawings and Prints (an estimated 150,000 works!).

In 1944, as Lasansky’s Guggenheim Fellowship was coming to a close, University of Iowa president Virgil Hancher was looking for a Printmaker in Residence as part of the development of the University Art Department. Mauricio Lasansky accepted the position and while he initially planned on being in Iowa City for “just a year”, Lasansky taught at the University for forty years and established one of the most respected printmaking workshops in the country. By all accounts Lasansky was an exceptionally dedicated teacher; in his farewell letter to the director of the University Art Department in 1984, he wrote:

“Somehow I will miss teaching since I don’t recall one day in my teaching one-to-one that was not enjoyable. For that I am grateful to the University, the Art Department, and above all to my students, who are scattered all over the world as you know. I can honestly say that I did the best I could. Was it good enough? Time will say.”

-Letter to the Director of School of Art & Art History. Oct. 31, 1984 file: Lasansky, Mauricio. Vita and Farewell Correspondence, 1983-1984 collection: Iowa Print Group Records

Throughout his time teaching, Lasansky continued to earn accolades for his own work – in fact, in 1961, Time magazine called him “the nation’s most influential printmaker”.

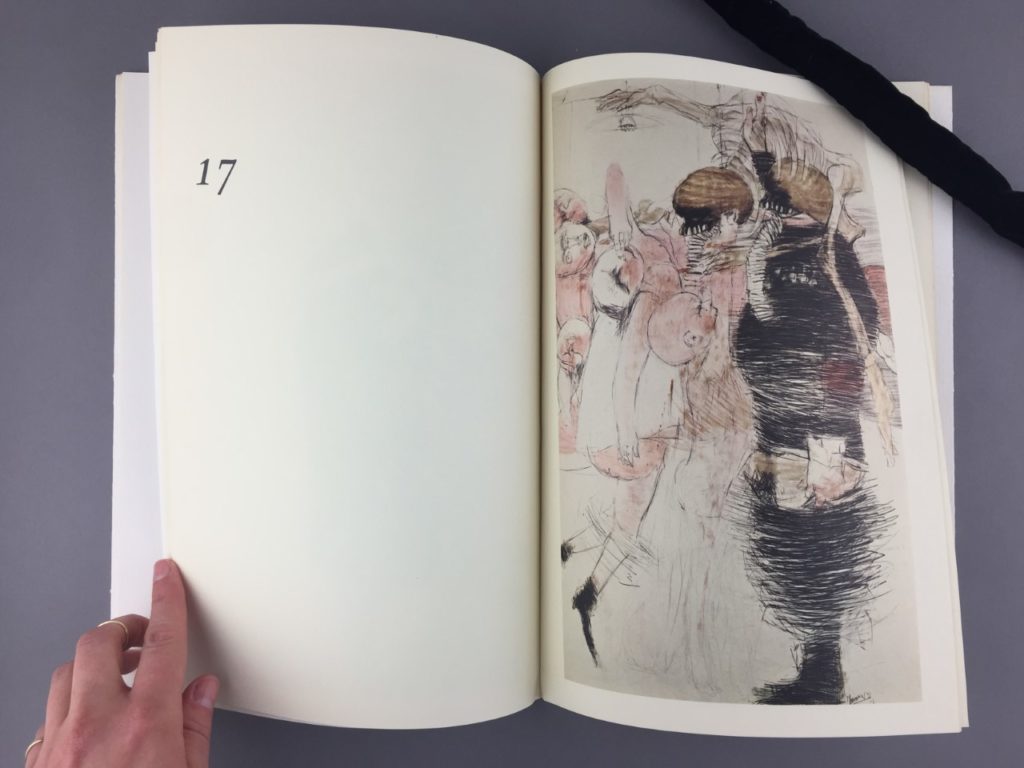

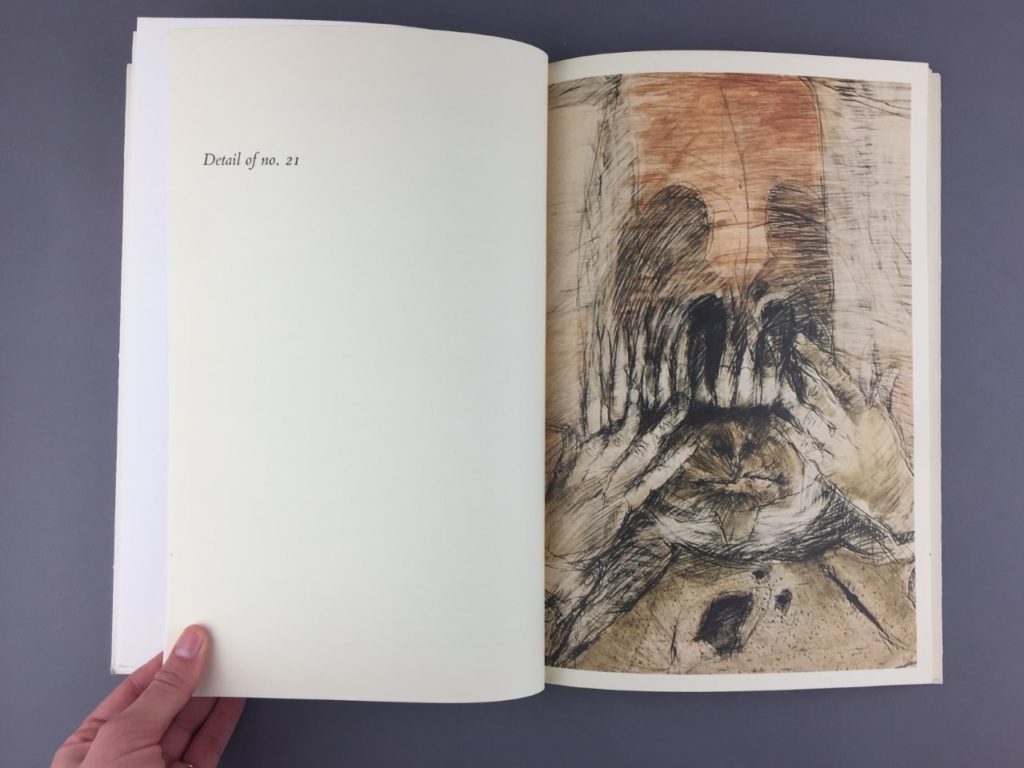

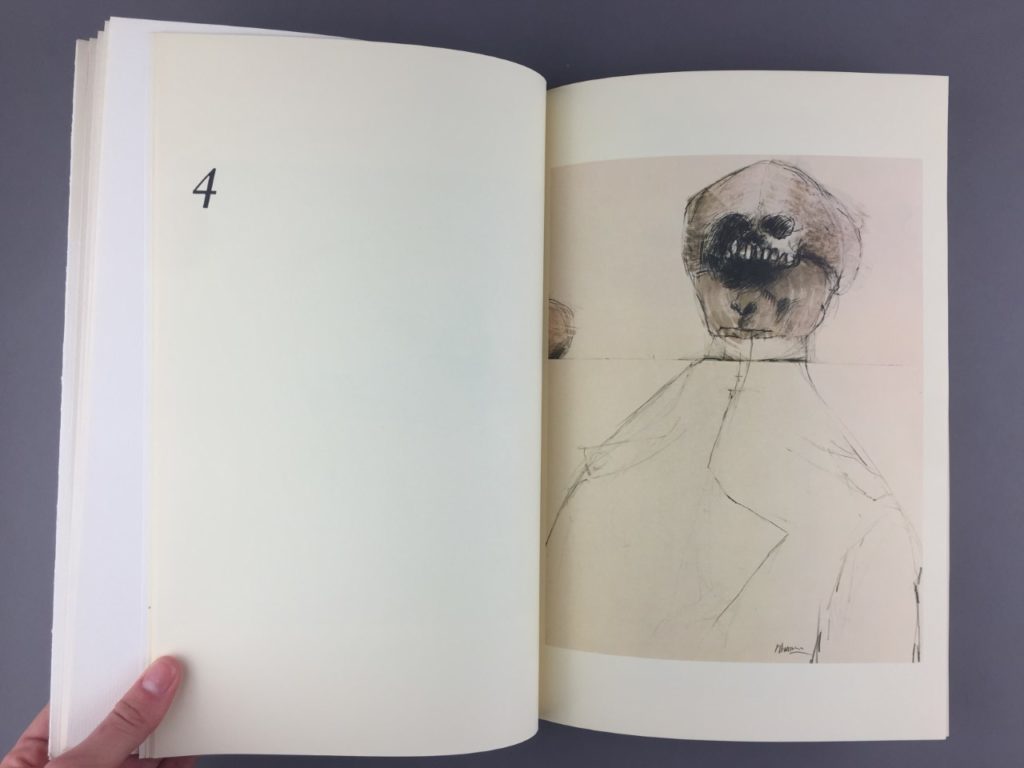

Because of his skill and success as a printmaker, it is somewhat surprising that Lasansky’s most famous works are a suite of drawings. The Nazi Drawings — a set off 33 portraits of Nazis, other perpetrators of the Holocaust, and bystanders — are haunting depictions of the disgust and pain that Lasansky felt about the Holocaust and atrocities of World War II. Created over a period of five years, the drawings are made primarily with pencil on paper, with some treatments of turpentine, earth colors, and collaged newspaper. With simple materials, Lasansky was able to conjure a thick layer of horror and tragedy onto paper. The drawings vary in size: a few measure about two feet in height, but the majority are around five feet—and the largest is almost seven feet tall. The scale of these works makes them feel unescapable, they violently confront the viewer with deeply dark depictions of humanity. To see a grotesque image as a sketch on a page is one thing, but these large drawings force us to see the figures as the same size as us. They are fully disturbing.

Although the end of World War II and the liberation of concentration camps occurred in 1945, Lasansky would not begin work on his drawings until 1961. This gap in time is because, like many people around the world, he did not fully know the extent of the tragedy until decades after the war. Immediately following the war, media attention on the Holocaust was minimal, and it was only years later that stories of the persecution and genocide of Jewish people and other groups were introduced into wider public consciousness.

As an example, one of the most famous works of literature to come out of the Holocaust, Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl, would not be published in Amsterdam until 1947 – and only after great effort by her father Otto Frank. As a post by the Anne Frank House explains, “It was not easy to find a publisher so soon after the war, because most people wanted to look to the future.” Similarly, an English translation of the book for publication in the United States was turned down by 10 publishers before Doubleday Publishers agreed to publish the translation in 1952. The diary is undoubtedly a vital piece of history, but the writings are about Anne’s quiet life in hiding — the reality of genocide and the horrors of labor and death camps were not included in the published volume. The climate of the 1950s was heavy with post-war optimism and American society at large was saturated with a culture of positivity; most people preferred not to grapple with the tragedy and grief of the Holocaust.

For many, full recognition of the horrors of the Holocaust was spurred by the widely publicized 1961 trial of Adolf Eichmann, a German Nazi officer and one of the major organizers of the Holocaust. Eichmann was responsible for the logistical planning of genocide and escaped capture at the end of the war. In 1960, Nazi hunters found Eichmann living in Argentina and brought him to Israel to stand trial for 15 criminal charges. This trial was broadcast around the world, from April to October of 1961, and people watched on their televisions as over 90 Holocaust survivors gave testimony about the horrors of the Holocaust and the brutality of the Nazis. There had never before been this level of exposure for Holocaust survivors and the terrible truth of their experiences. During the Nuremberg Trials, for example, only 3 Holocaust survivors gave testimony because the prosecution decided to rely on documentary evidence in building their case. The Eichmann trial was widely followed by the media and exposed many people, including Mauricio Lasansky, to the truth about the horrors of the Holocaust.

In The Nazi Drawings, Lasansky was putting his rage and grief onto paper. In a biographical essay, scholar Alan Fern summarizes:

“Both the formal and the iconographic development of Lasansky’s work reached a climax in The Nazi Drawings of 1961-1966. For Lasansky, this was both an artistic watershed and an emotional catharsis, during which he turned his major creative energies away from the print to give physical embodiment to his seething reaction against the Nazi holocaust. He saw the unleashing of bestiality in Germany during the 1930s and 1940s as a brutal attack on man’s dignity, and felt it carried the potential seeds of man’s self-destruction.”

– “The Prints of Mauricio Lasansky” by Alan Fern (page 17) in Lasansky: Printmaker John Thein, Phillip Lasansky – University of Iowa Press 1975

Even with greater public awareness of the Holocaust, The Nazi Drawings were difficult for many to stomach. In 1967 Time magazine noted that the works were on display at the Whitney Museum and called them “as unsettling a set of drawings as any museum has shown in years” and reported “the impact of the drawings is so devastating that the Chicago Institute of Art declined to show them altogether…” With just pencil and paper, Lansky managed to illustrate intensely uncomfortable images and convey the immense tragedy of the Holocaust. The Nazi Drawings are an example of the power of art as process – they were a way for Lasansky to lance the wound and pour out the heavy emotions he felt. The drawings have also endured as an example of the power of art to unsettle viewers; to provoke emotional reactions from an audience. No one would venture to call these drawings beautiful, but there is no mistaking their power.

The entire set of drawings are currently on display for the first time in over 15 years at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. This exhibit, on display until June 26th, pairs the drawings with archival media of the Eichmann trials as well as contemporary prints by Lasansky.

Undoubtedly significant to the rise of printmaking in the United States, Mauricio Lasansky’s legacy is also deeply imprinted on Iowa City. The tradition of excellence he established continues in the University of Iowa’s printmaking program, and members of Laskansky’s family run The Lasansky Corporation Gallery on Washington Street in downtown Iowa City.

————

As another way of remembering this difficult time in history, on April 29th, 2022 the University of Iowa will plant a new tree on the Pentacrest: a sapling propagated from the old chestnut tree that grew behind the Amsterdam annex where Anne Frank and her family hid during WWII. Learn more about the event here.

Books in Special Collections:

– The Nazi Drawings / by Mauricio Lasansky FOLIO NE539.L3 N3 1976

– Lasansky, Printmaker FOLIO NE594.L3 T44

Material in University Archives:

– Papers of Mauricio Lasansky University Archives RG 99.0030

– Iowa Print Group Records RG 06.0007.002

– Howard N. Sokol Papers (RG 99.0017) Subject Files – L. Lasansky, The Nazi Drawings 1972.

Box 3.

View more digitized photos of Lasansky (from the University Archives) as well as digitized prints (from the collection of the Stanley Museum of Art) at the Iowa Digital Library

Also be sure to check out Lasansky’s collection at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art