The following is written by Olson Graduate Research Assistant, Rachel Miller-Haughton The Civilian Conservation Corps was a program established in 1933 under Franklin Delano Roosevelt to provide jobs for “young, unemployed men during the Great Depression.” As a program, it existed for 9 years and employed about 3 million men across the country, ages 17 to 28,Continue reading “Civilian Conservation Corps, Civilian Climate Corps: The CCC Then and Now”

Category Archives: Educational

Stepping into the life of Julia Booker Thompson

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Alexa Starry from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0001) Stepping into the life of Julia Booker Thompson Alexa Starry Cookbooks are a wonderful wayContinue reading “Stepping into the life of Julia Booker Thompson”

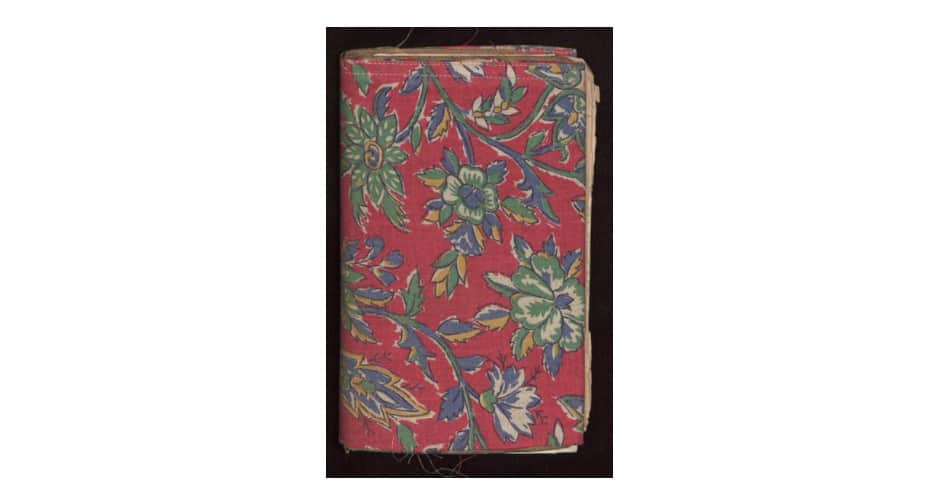

17th Century Armenian Bookbinding Traditions

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Natasha Otteson from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0001) 17th Century Armenian Bookbinding Traditions By Natasha Otteson The University of Iowa Libraries has aContinue reading “17th Century Armenian Bookbinding Traditions”

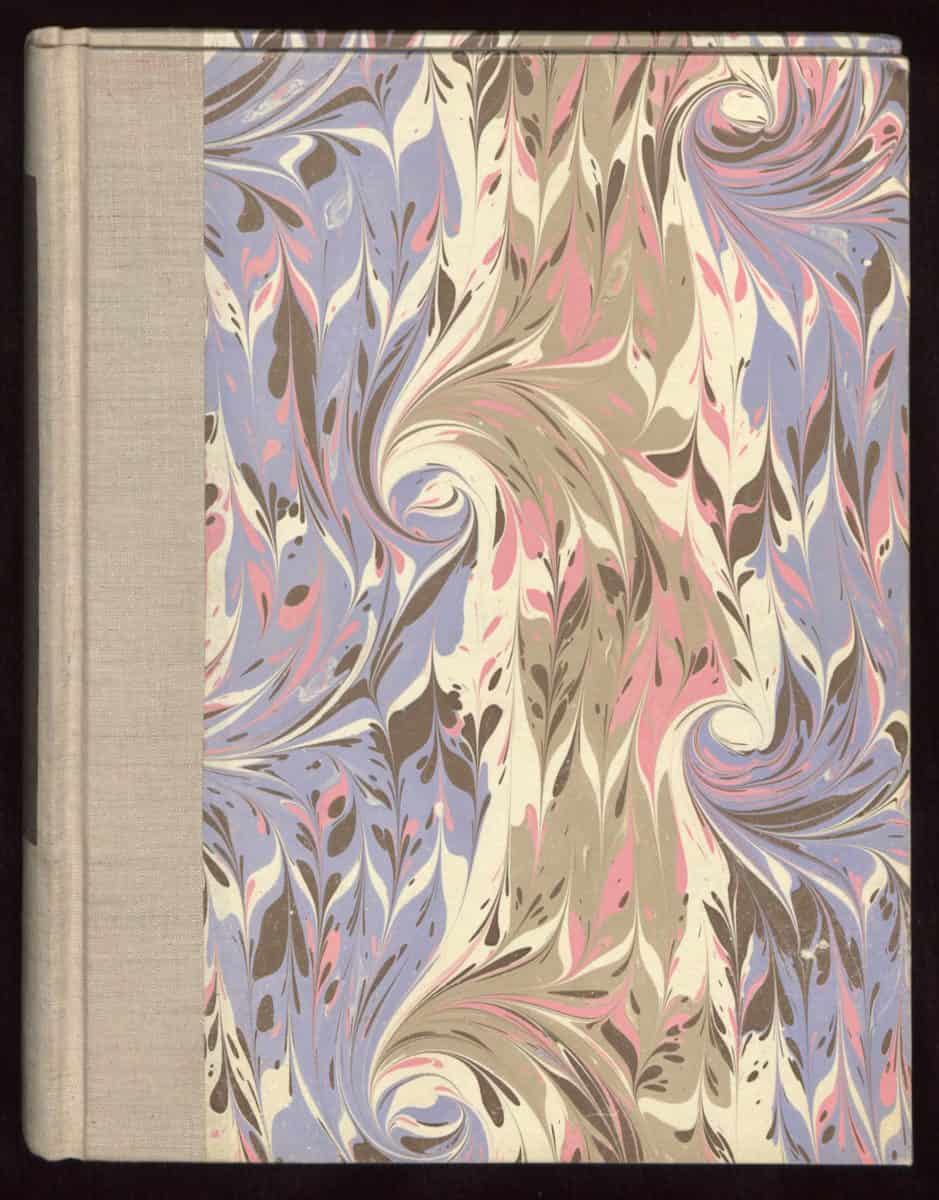

Cookbooks, Citation, and Community

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Breanna Himschoot from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0001) Cookbooks, Citation, and Community By Breanna Himschoot Under its bright lavender marbled binding, this handwrittenContinue reading “Cookbooks, Citation, and Community”

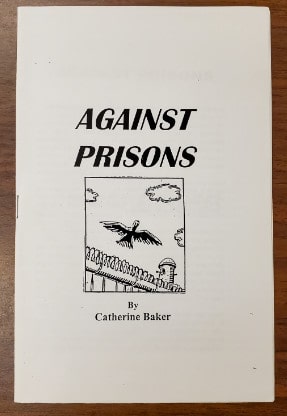

From the Classroom- Steal This Zine!

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Jacob Roosa from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0EXW) Steal This Zine! By Jacob Roosa No, really, steal this zine. Examples of anti-copyright noticesContinue reading “From the Classroom- Steal This Zine!”

Summer Seminar Series is Here

On June 11 University of Iowa Libraries Special Collections started their Summer Seminar Series! This online series features Special Collections & Archives staff talking about what we know best: our collections and our favorite topics featured in the archives. This series of 15-30 minute presentations are recorded, so if you can’t join us for ourContinue reading “Summer Seminar Series is Here”

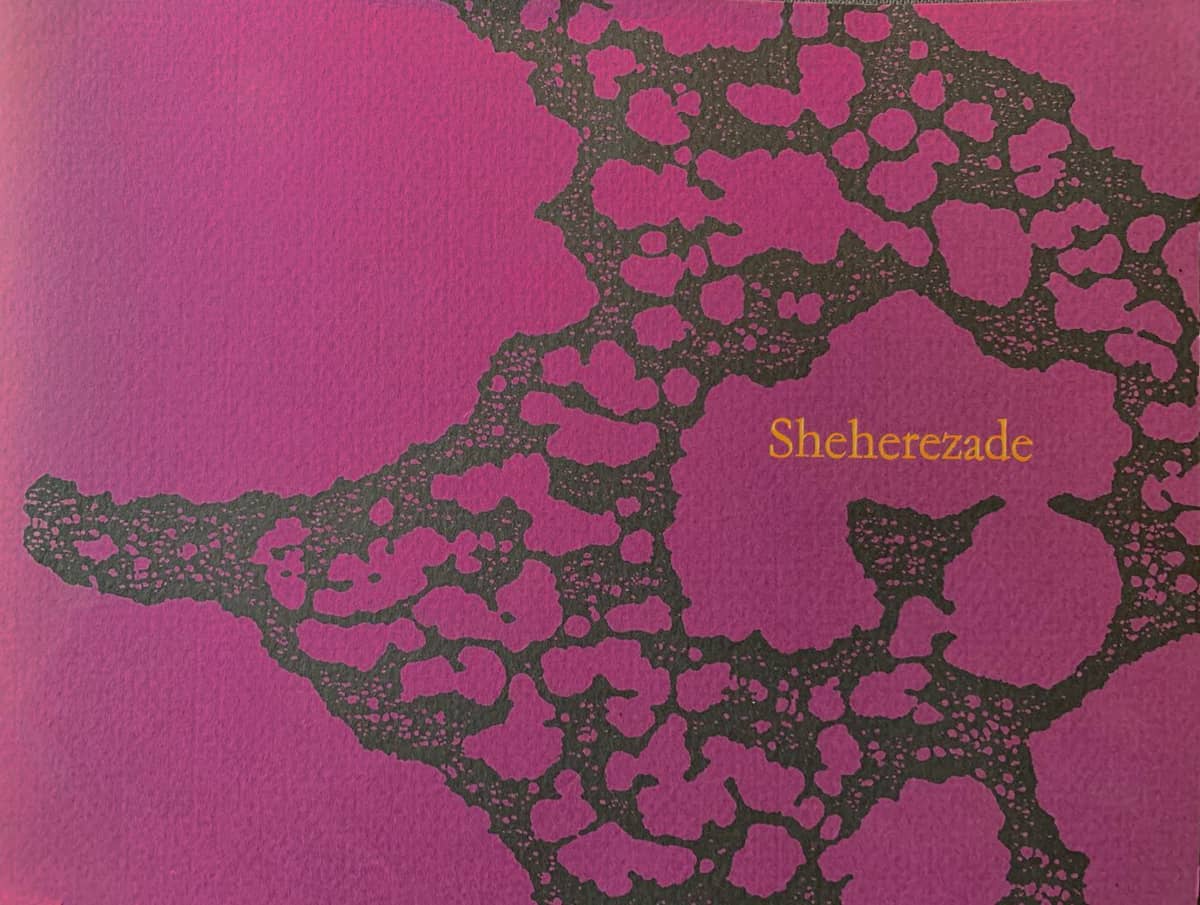

From the Classroom- Sheherezade: a flip book

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Leslie Hankins from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0EXW) Sheherezade: a flip book By Leslie Hankins The bold imperial purple cover with the title,Continue reading “From the Classroom- Sheherezade: a flip book”

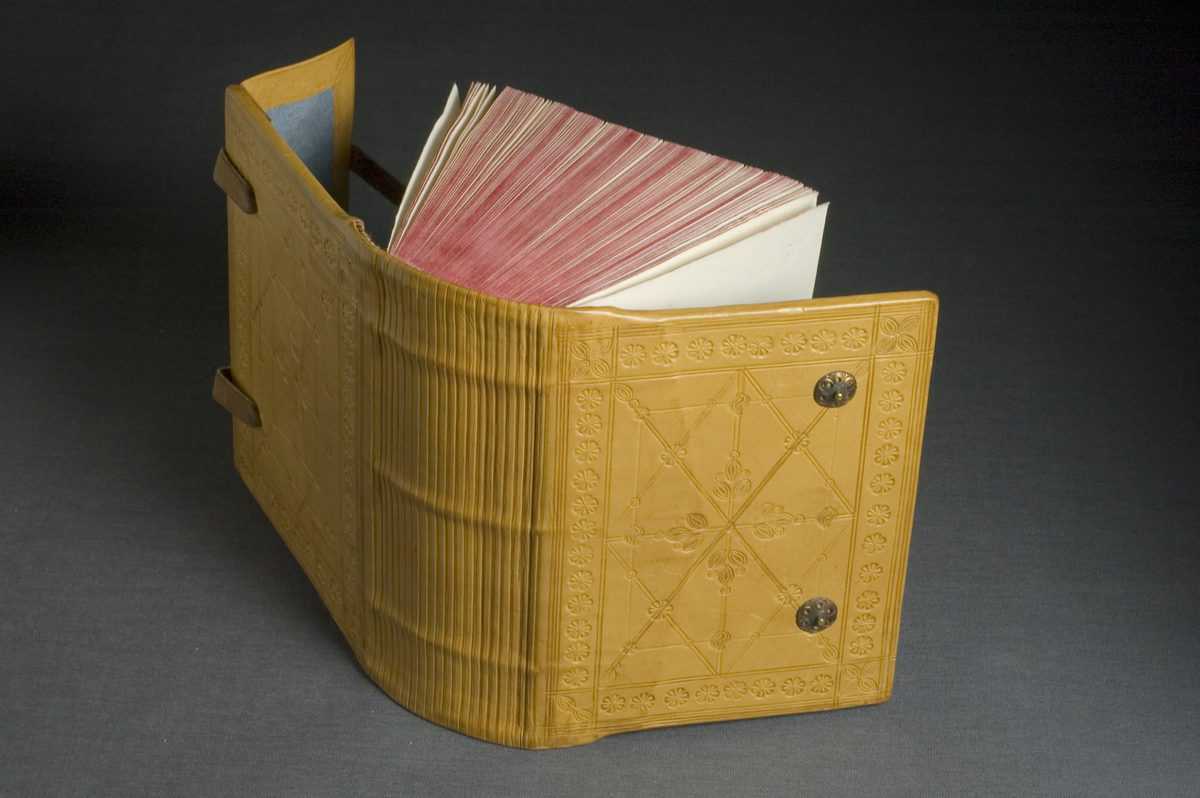

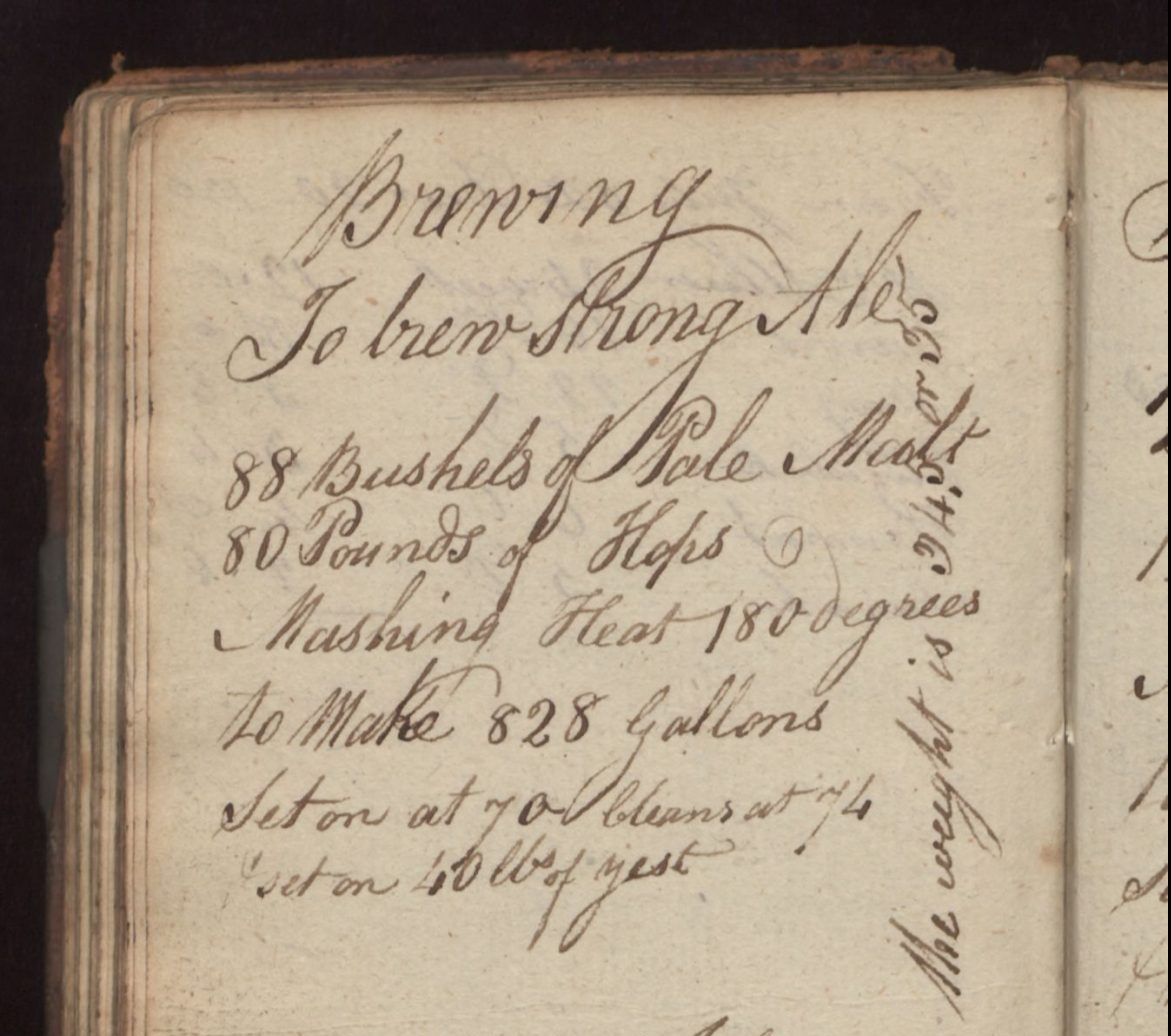

From the Classroom–Business, Beer, and the Bible: The Case of the Maude’s Commonplace Books

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Elizabeth McKay from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0EXW) AMERICAN COOKERY MANUSCRIPTS: MAUDE, WILLIAM & JOHN. Brewer’s Duties & Commonplace Books (2), Early 19th Century,Continue reading “From the Classroom–Business, Beer, and the Bible: The Case of the Maude’s Commonplace Books”

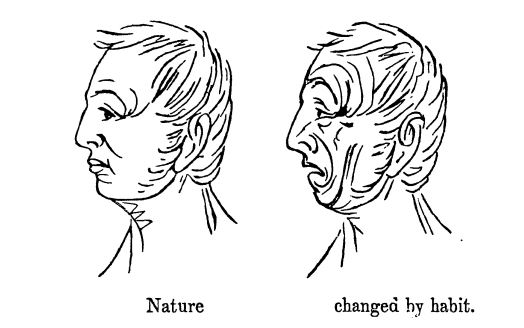

Shut Your Mouth and Save Your Life: 1870 health book resonates in the era of protective masks

The following blog comes from Olson Graduate Assistant Rich Dana, who interviewed Marvin Sackner on his collection of concrete and visual poetry. Among the over 75,000 items in the newly-acquired Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry, there are many unique and one-of-a-kind art objects and artists’ books. Along with original artwork, there is anContinue reading “Shut Your Mouth and Save Your Life: 1870 health book resonates in the era of protective masks”

A Virtual Bibliophiles

Today is April 8th, 2020, the day we were supposed to gather for the last Iowa Bibliophiles of the academic year. The plan: come together, eat some tasty snacks, and explore some of the highlights from our collection with the help of our wonderful student workers. Our students had selected manuscripts, books, and more, researchedContinue reading “A Virtual Bibliophiles”