In 1977, Des Moines civil rights activist, Edna Griffin, wrote a strongly worded opinion piece defending the a local dance studio, the Gateway Dance Theatre. But why? In this piece, IWA student assistant Kelly Kemp explores the connection between civil rights and dance through the papers of Gateway’s founder, Penny Furgerson.

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Done biting their tongues: UI dental hygiene and gender discrimination

by Beatrice Kearns, graduate assistant, Iowa Women’s Archives The University of Iowa Dental Hygiene Program began in 1953 with 24 students and despite being nationally renowned, the female-dominated program did not make it to its 50th anniversary. Until the final graduating class in 1995, the program trained hundreds of hygienists. Students took classes in aContinue reading “Done biting their tongues: UI dental hygiene and gender discrimination”

Women, Disability, and Reparative Description in IWA

The following post was written by IWA Student Specialist, Abbie Steuhm. In the process of creating a LibGuide on women and disability for the Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA), I discovered a trove of artifacts from disabled women and disability advocates. However, this did not come easy as the history was hidden by its description. IContinue reading “Women, Disability, and Reparative Description in IWA”

Kick Off Women’s History Month with the Iowa Women’s Archives

The Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA) will kick off Women’s History Month with an event at the Iowa City Public Library! The Purpose of the Pelvic: A Historical Analysis will bring Dr. Wendy Kline, the Dema G. Seelye Chair in the History of Medicine at Purdue University, to discuss the history of the pelvic exam andContinue reading “Kick Off Women’s History Month with the Iowa Women’s Archives”

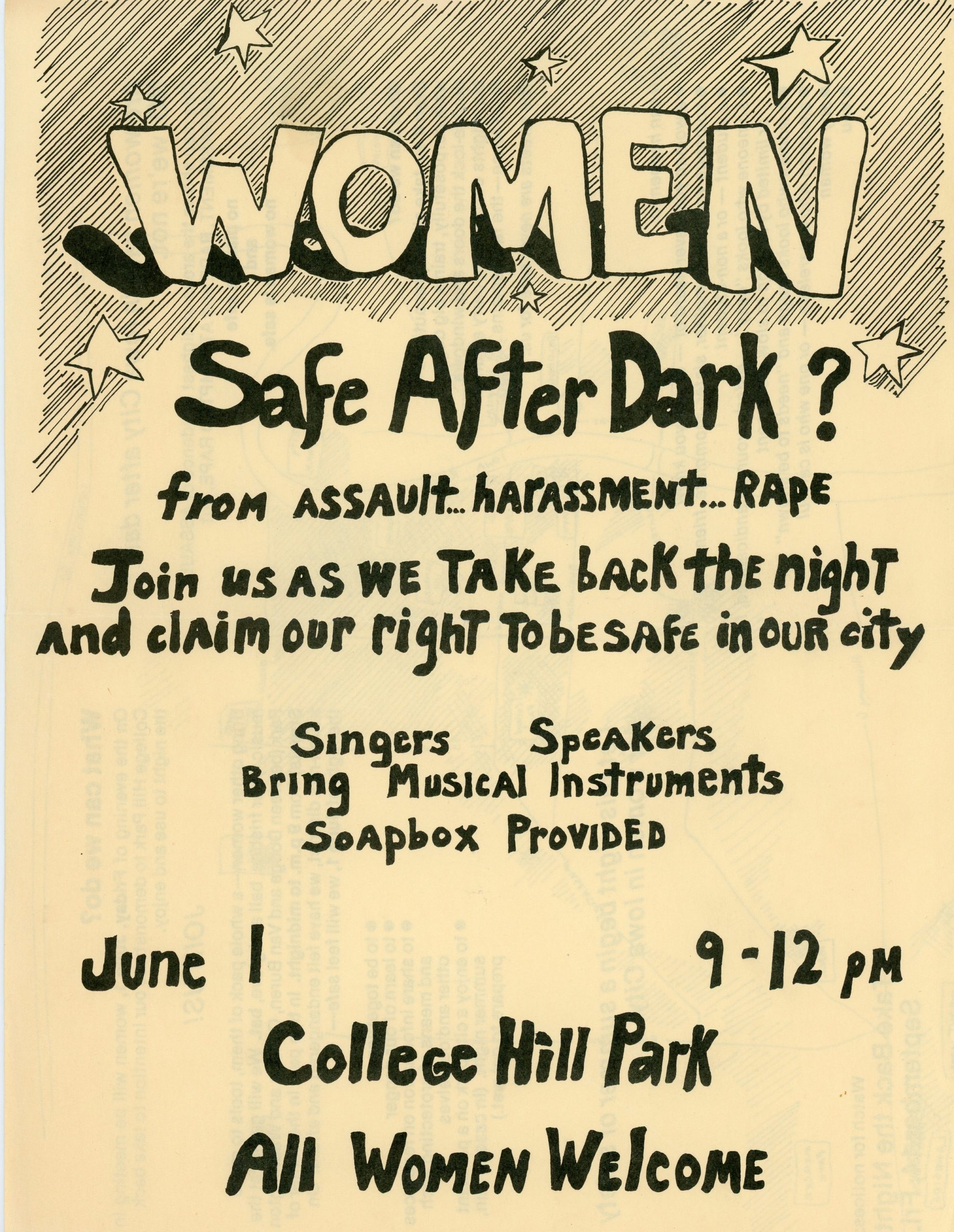

Women Safe After Dark? The Beginnings of Take Back the Night at the University of Iowa

On September 12, 1979, an advertisement for a rally appeared in the campus newspaper, the Daily Iowan. The outline of a woman with bows and arrows, shooting into the night sky was accompanied with the promise, “Friday evening at 8 p.m., the women of Iowa City will have a chance to support each other inContinue reading “Women Safe After Dark? The Beginnings of Take Back the Night at the University of Iowa”

Kittredge Cherry and Audrey Lockwood: A Love Story

This post was written by IWA Student Specialist, Abbie Steuhm. The LGBTQ+ community has grown in incredible size and visibility in the last decade. The legalization of same-sex marriage in the U.S. in 2015 was a colossal milestone for LGBTQ+ rights, and it has arguably helped in the normalization and acceptance of LGBTQ+ people nationwide.Continue reading “Kittredge Cherry and Audrey Lockwood: A Love Story”

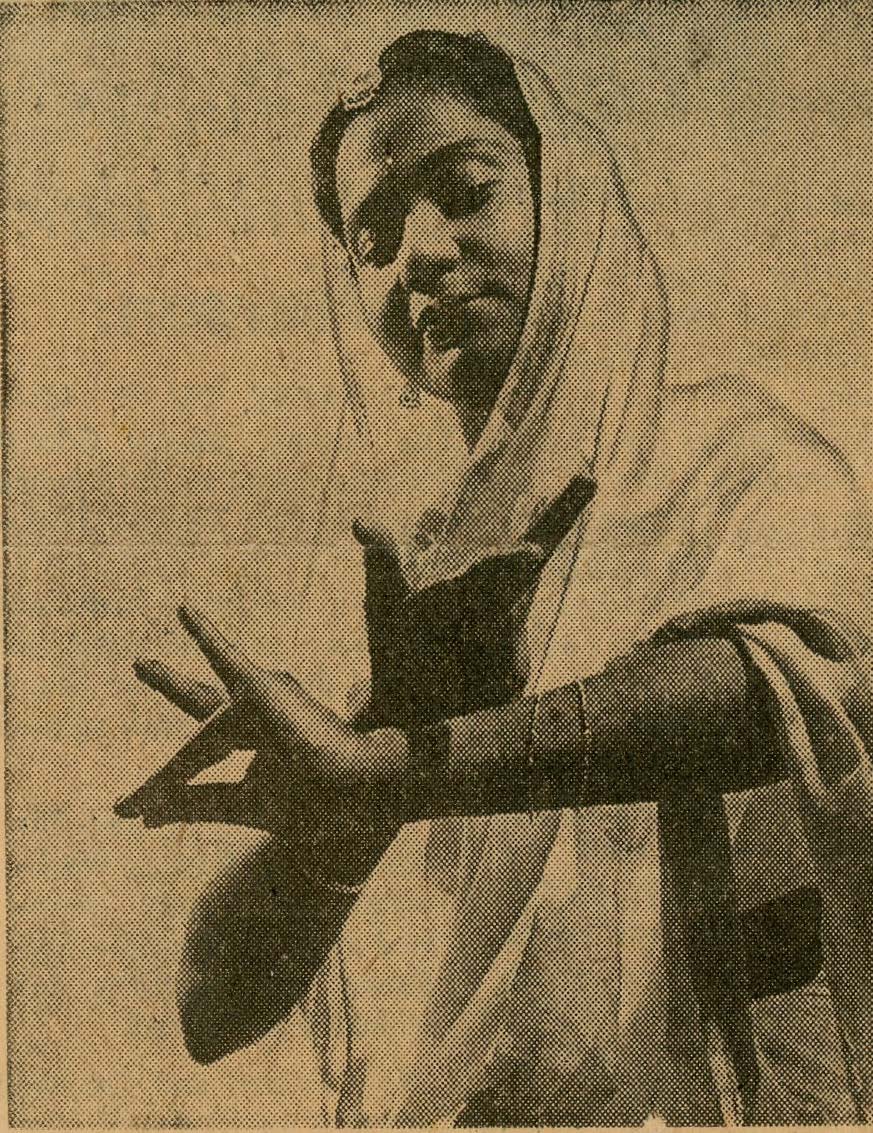

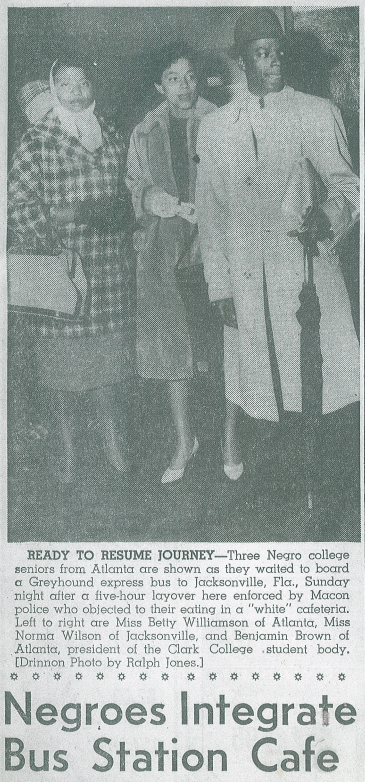

Civil Rights Trailblazer June Davis Donates Papers to IWA

This post is by Archives Assistant Heather Cooper. The Iowa Women’s Archives recently received the first installment of a new collection of personal papers from Norma June Wilson Davis. Davis, who later became an administrator at the University of Iowa, was at the forefront of the student civil rights movement in Atlanta, Georgia, in theContinue reading “Civil Rights Trailblazer June Davis Donates Papers to IWA”

Disability Rights in the Elizabeth Riesz Papers

The following post was written by IWA Student Assistant, Abbie Steuhm. The Disability Rights Movement has seen great progress and recognition in recent years; however, as with most social movements, the historic past for disabled people is one of severe discrimination and offensive, prejudiced, and even racist language. On January 30, 1972, Anthony Shaw, M.D. published anContinue reading “Disability Rights in the Elizabeth Riesz Papers”

IWA’s 2021 Kerber Grant Recipient Finds Personal Stories within Industrial Agriculture

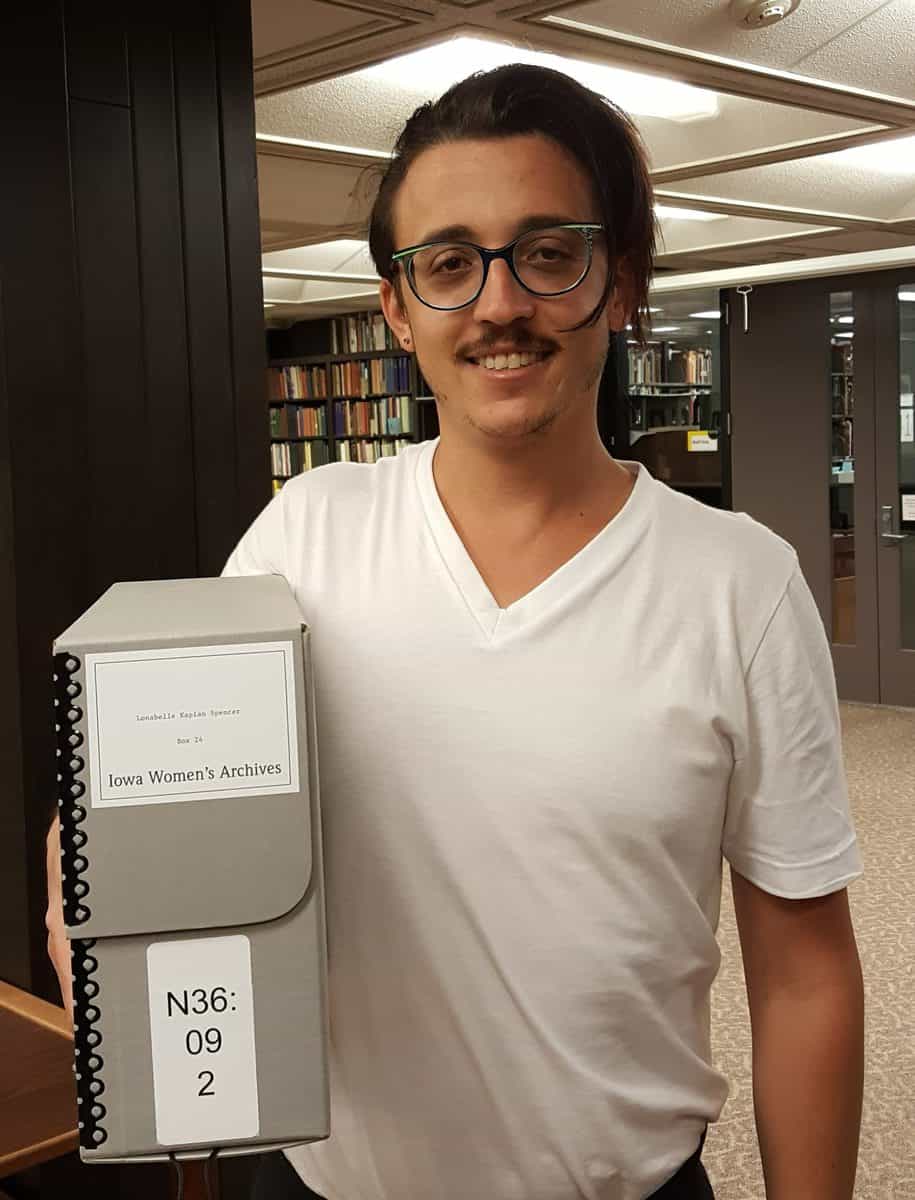

In Box 24 of the Lonabelle Kaplan Spencer papers, Andrew Seber finally found exactly what he was looking for: personal testimonies by rural citizens whose lives were turned upside down by the development of hog confinements near their Iowa homes. Seber’s dissertation, Neither Factory nor Farm: the Other Environmental Movement, will focus on industrial animalContinue reading “IWA’s 2021 Kerber Grant Recipient Finds Personal Stories within Industrial Agriculture”

What Would You Attempt to Do If You Knew You Could Not Fail?

This post is by IWA Graduate Assistant Erik Henderson Taking a risk can be one of the most difficult things you must do. However, how would it feel knowing that you cannot fail no matter what you do? One thing that holds us back in life is our clouded judgment when making a major move.Continue reading “What Would You Attempt to Do If You Knew You Could Not Fail?”