by Beatrice Kearns, graduate assistant, Iowa Women’s Archives

The University of Iowa Dental Hygiene Program began in 1953 with 24 students and despite being nationally renowned, the female-dominated program did not make it to its 50th anniversary. Until the final graduating class in 1995, the program trained hundreds of hygienists. Students took classes in a wide range of subjects such as pharmacology, anatomy, oral pathology, and community health-based coursework. In the beginning, students earned a certificate from the College of Dentistry (COD) and could choose to complete a BA in the College of Liberal Arts and Science. After 1967, all students earned BAs through the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and in 1969 a dental hygiene major was approved. Student life of those studying dental hygiene was robust. Student chapters of the American Dental Hygienists Association, honors fraternities, and social clubs kept students busy. Students were expected to be knowledgeable of the anatomy of the head, neck, and mouth. This required the use of unique materials and methods of study. They were expected to identify any given tooth, spot abnormalities, and understand the development of healthy teeth.

The program was dominated by female students, as was the profession. When the American Dental Hygiene Association wrote their first bylaws in 1923, they used exclusively female pronouns. However, in 1964, they changed their Constitution to be gender neutral.

The dental program at the University of Iowa has a rich history, it is the first dental department west of the Mississippi river and the sixth oldest in the entire country. Dental hygienists have a long history as well, with the first program being opened in 1913 in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Hygienists focus in narrowly on the cleanliness of the mouth and teeth and preventative care, whereas dentists focus more on repairing damage and other oral health concerns. However, dental hygienists are not associated with the same prestige as dentists.

The program at the University of Iowa emphasized the professionalization of dental hygiene, hosting conferences and engaging in research. Faculty wanted to demonstrate the evolution of a knowledge-based profession, legitimizing dental hygienists as healthcare workers. There was also a strong tie to community service, many courses included outreach and service. The program hosted field trips for local school-aged children and educated them on the importance of oral hygiene. Despite this, hygiene students were often discredited and not taken as seriously as other dental students.

At right: Pins, 1983. University of Iowa Department of Dental Hygiene records, Iowa Women’s Archives, University of Iowa Libraries.

The Experimental Expanded Function study was a controversial look at broadening the tasks of dental hygienists. After learning about anesthesiology, periodontics, and other advanced topics, hygiene students were blindly examined against dental students. Results demonstrated that they performed on comparable levels, showing that hygienists were on par with students getting advanced medical degrees. Dental hygienists were not given the same respect and fought for their recognition. This demonstrates the evolution of the profession, from cleaning and polishing teeth to administering care and advocating for patient wellness.

At left: Dental Hygiene students studying in 1993

The UI Dental Hygiene Program was reviewed and recommended for closure in 1992. This was met with backlash from faculty and students. The university was looking to reduce spending over a four-year period. Three tenured faculty members, Pauline Brine, Elizabeth Pelton, and Nancy Thompson filed a lawsuit claiming that this closure was discriminatory against the woman-dominated program. They also claimed retaliation as faculty had been concerned about treatment and pay discrepancies within COD. The female faculty were routinely called “Mrs./Ms.” instead of “Dr./Professor” like their COD male counterparts. They were called hysterical and referred to as “Pauly’s puppets” referencing Pauline Brine, the department head. Their salaries did not grow at the same rate as faculty in the COD. Students were also treated unfairly. During exams, they were told they were not to answer certain questions despite being enrolled in the same classes with dental students, felt out of the loop of COD communication, and were called “genies” by others within the COD, including by instructors in front of classes.

There were several programs brought up as potential for closure; library and information science, undergraduate-level social work, and dental hygiene to name a few. These are all historically dominated by women. In the fall of 2023, the School of Library and Information Science has an 86% female enrollment, undergraduate social work has 89% female enrollment, and the graduate program has 80% enrollment, and these have continued to be female-dominated programs at Iowa.

The university was concerned that female students were not enrolling in traditionally male-dominated programs because of the presence of female-dominated ones. One member of the Board of Regents, Mary Williams, staunchly disagreed with this claim, stating that the reason women weren’t enrolling in programs like medicine, law, and economics were because of “systematic exclusion of women by the gatekeepers”.

The lawsuit was heard in Des Moines, and a judge ruled that the university was not closing the department based on gender bias, but that the University did retaliate against the professors and violate their First Amendment rights. This ruling was appealed and overturned in the 8th U. S. Circuit Court of Appeals. The last class graduated from the program in 1995.

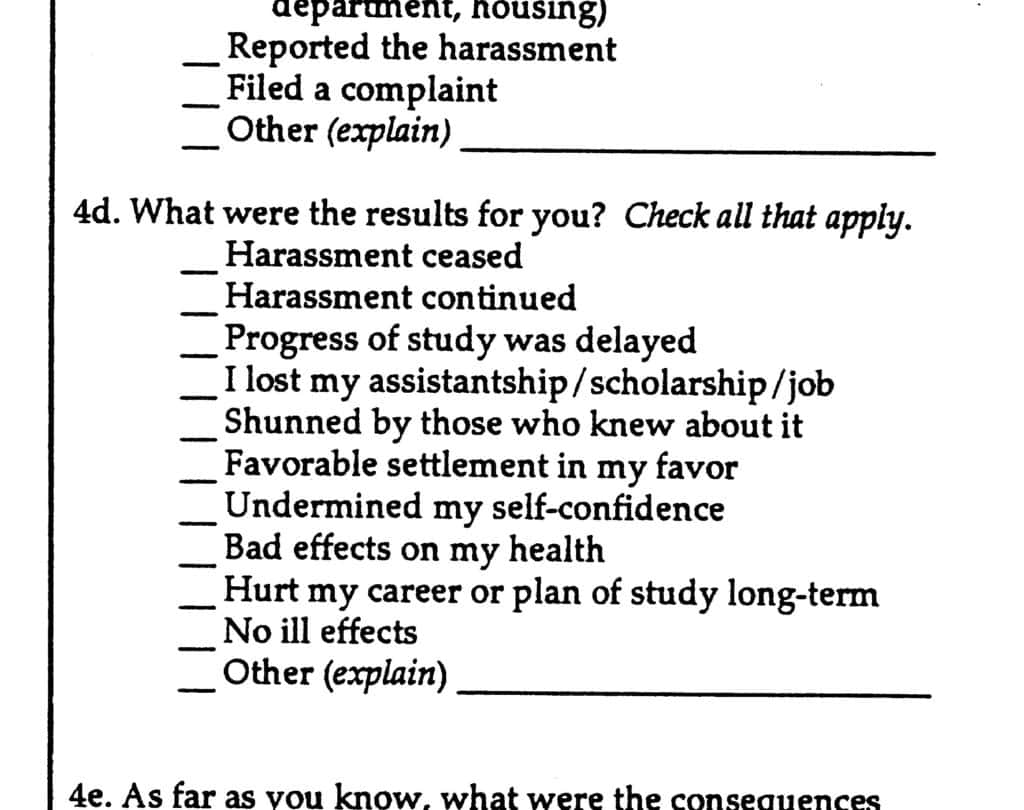

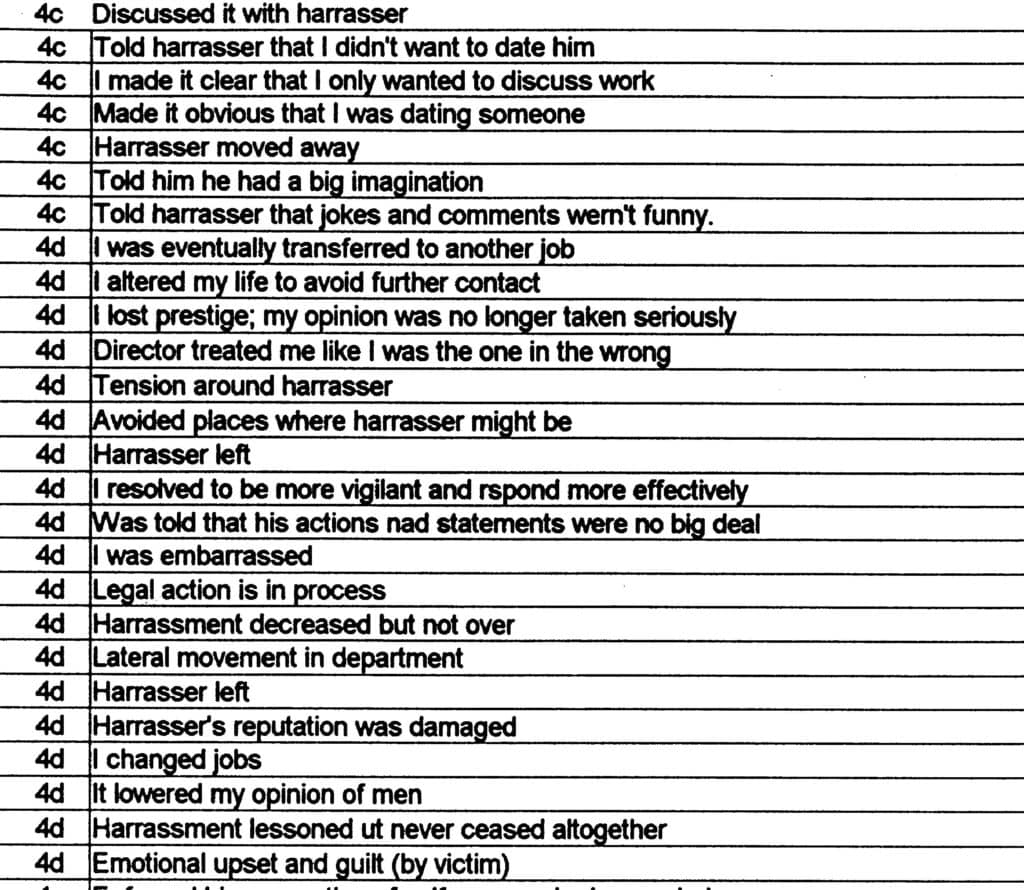

The controversial closure of the Department of Dental Hygiene is representative of a tumultuous time for women at the University of Iowa. Just a few years prior, the university lost a suit to Dr. Jean Jew, a professor in the anatomy department at the College of Medicine about sexual harassment and discrimination. A judge ordered the university to promote Jew, issue her back pay, and create a work environment free of sexual harassment. The Council on the Status of Women created a survey on sexual harassment, asking about experiences and consequences. The results show that many female students and faculty felt frustrated and disheartened by the process of reporting and lack of accountability for harassers.

Sexual Harassment Survey and results, 1993. University of Iowa Council on the Status of Women records, Iowa Women’s Archives, University of Iowa Libraries.

Gender discrimination in academia is an ongoing battle. The UI Department of Dental Hygiene ended in 1995 but gender minority students continue to fight for fair treatment and access in higher education.