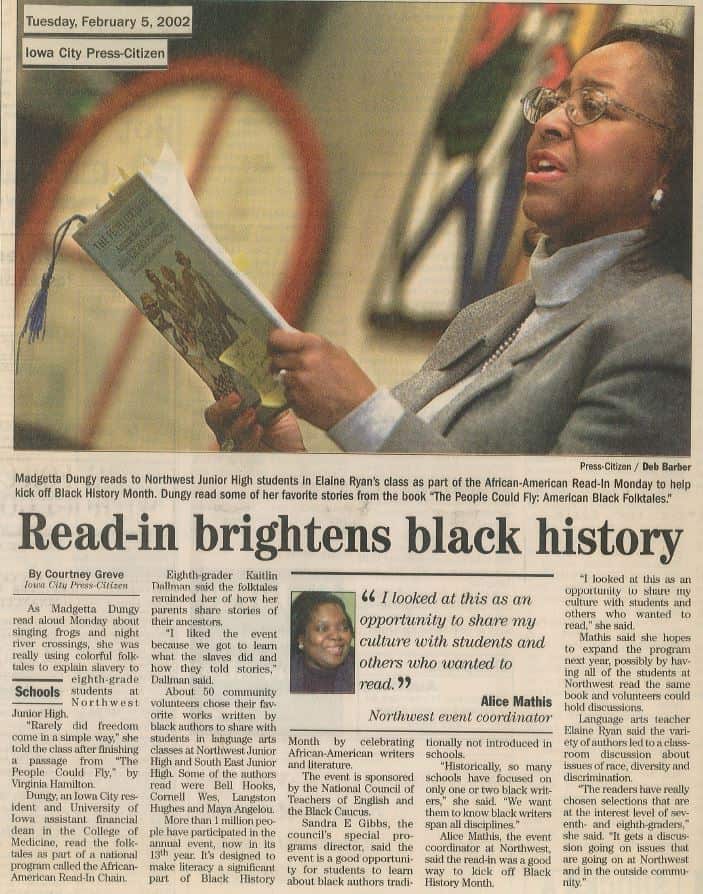

The following post is written by University of Iowa senior, Jack Kamp. When I started my internship at the Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA), I knew I was interested in working with Black women’s history. As a student interested in the history of civil rights and social justice, I knew that this collection would giveContinue reading “Student Reflection: Processing the Madgetta Dungy Papers”

Tag Archives: black history

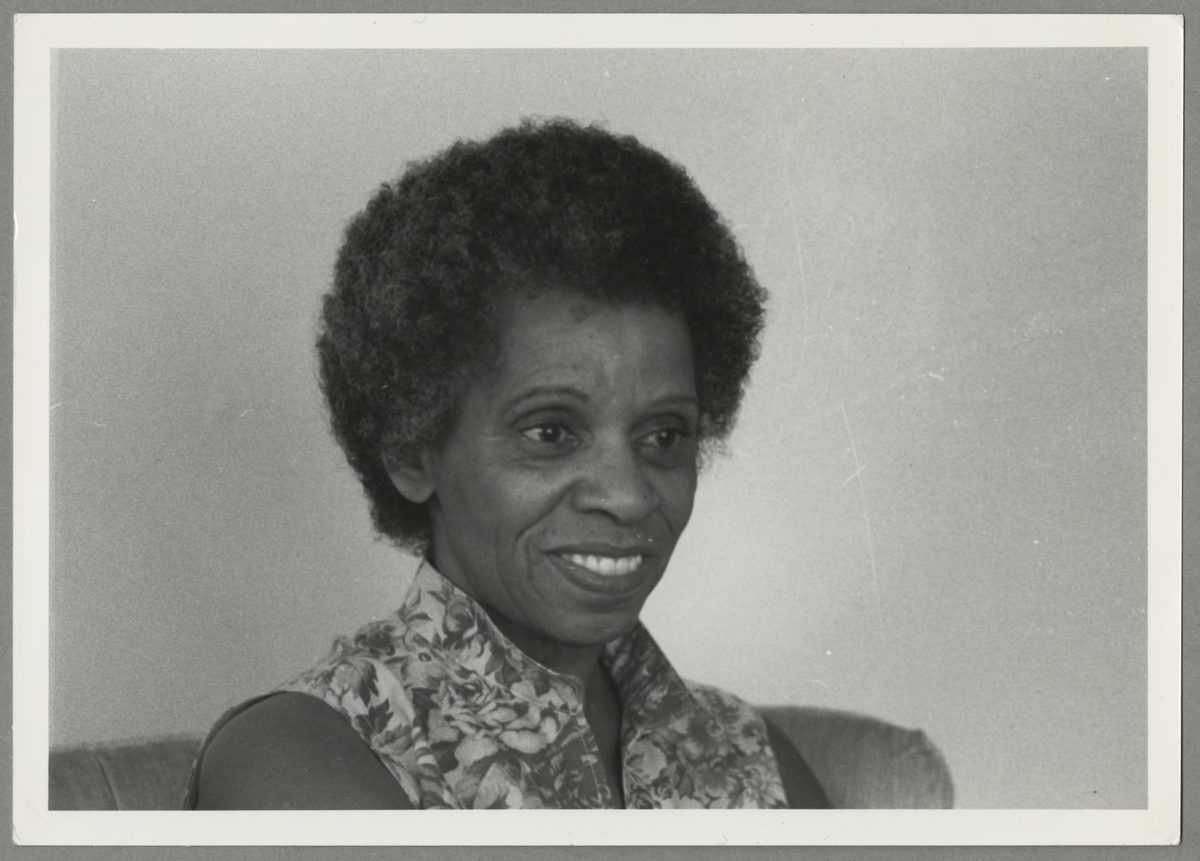

Edna Griffin, Civil Rights Activist

This post is the tenth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. This past summer, we have seen a nationwide movement for change. In Iowa City, Philadelphia, Chicago, Seattle,Continue reading “Edna Griffin, Civil Rights Activist”

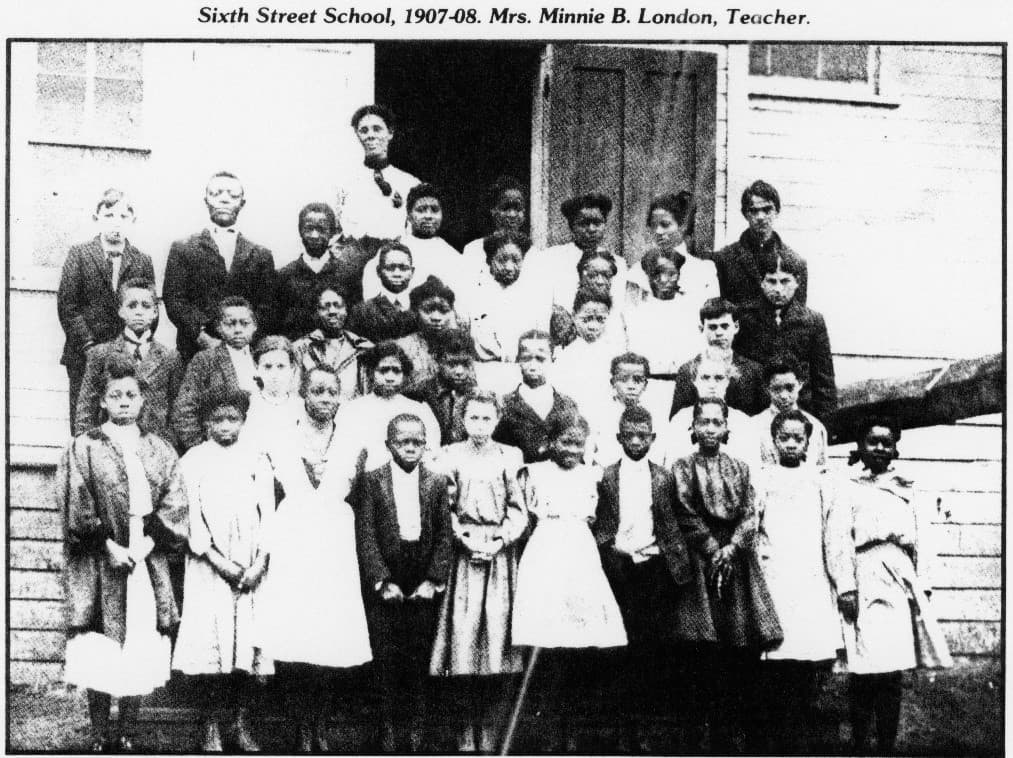

Reuben Gaines Memoir of Being Black in Buxton, Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Assistant, Erik Henderson, is the eighth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. The once prosperous coal mining town, Buxton, Iowa, approximately thirty minutes southwest of OskaloosaContinue reading “Reuben Gaines Memoir of Being Black in Buxton, Iowa”

Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader

This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the sixth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. Has anyone told you, you were going to be great in your youth?Continue reading “Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader”

Pauline Humphrey & African American Beauty Culture in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the fifth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. Over the past few months, social media has been filled with peopleContinue reading “Pauline Humphrey & African American Beauty Culture in Iowa”

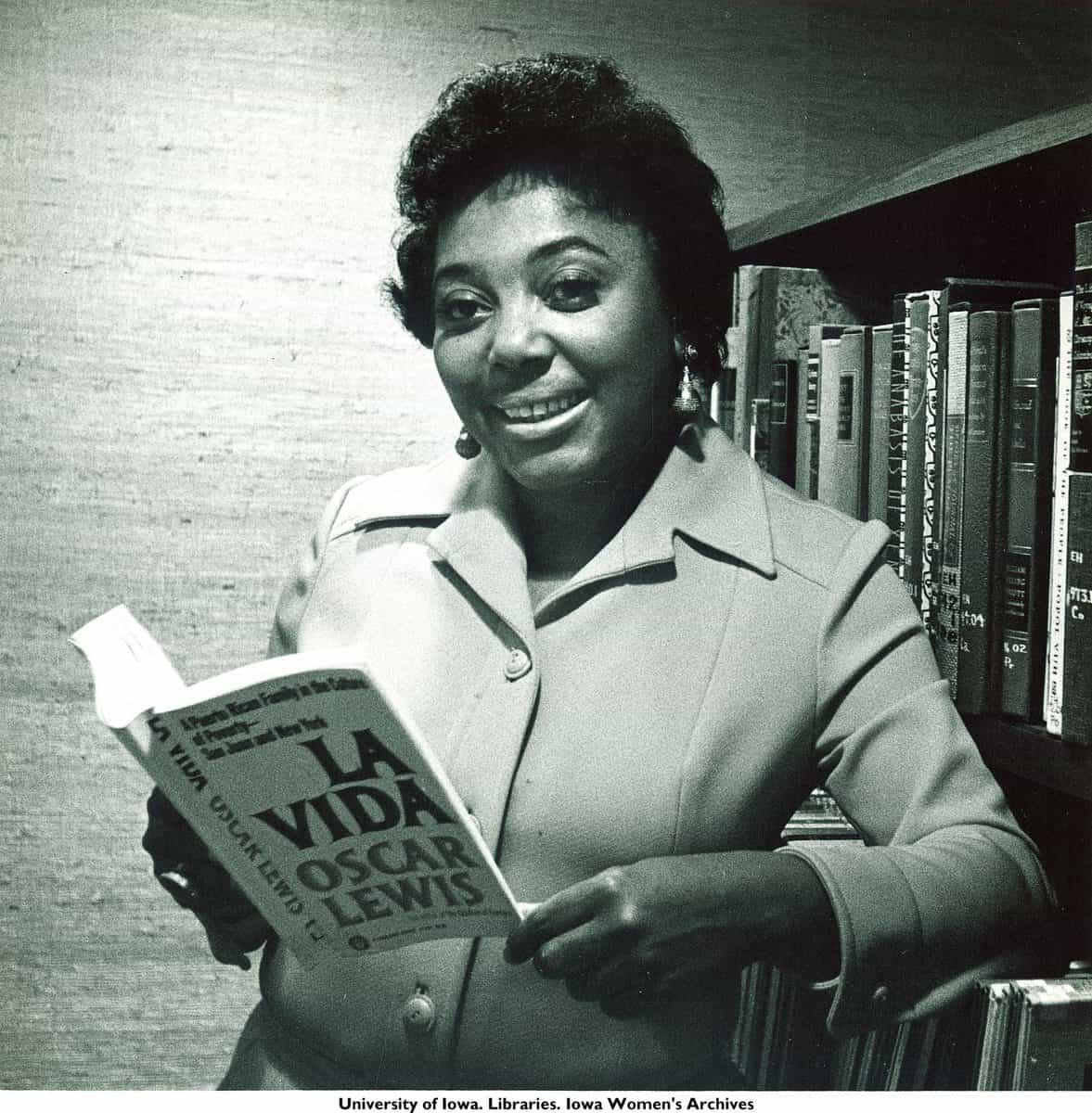

Encountering Soul in the Iowa Women’s Archives: Scholar Taryn D. Jordan and the Aldeen Davis Papers

Taryn D. Jordan was researching Ella Fitzgerald at the Schlesinger Library in the Radcliffe Institute when she first encountered the papers that would bring her to the Iowa Women’s Archives. Jordan is a doctoral candidate in Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies at Emory University and an ACLS Mellon Dissertation Completion fellow who has been researchingContinue reading “Encountering Soul in the Iowa Women’s Archives: Scholar Taryn D. Jordan and the Aldeen Davis Papers”