In 1977, Des Moines civil rights activist, Edna Griffin, wrote a strongly worded opinion piece defending the a local dance studio, the Gateway Dance Theatre. But why? In this piece, IWA student assistant Kelly Kemp explores the connection between civil rights and dance through the papers of Gateway’s founder, Penny Furgerson.

Tag Archives: des moines

What Would You Attempt to Do If You Knew You Could Not Fail?

This post is by IWA Graduate Assistant Erik Henderson Taking a risk can be one of the most difficult things you must do. However, how would it feel knowing that you cannot fail no matter what you do? One thing that holds us back in life is our clouded judgment when making a major move.Continue reading “What Would You Attempt to Do If You Knew You Could Not Fail?”

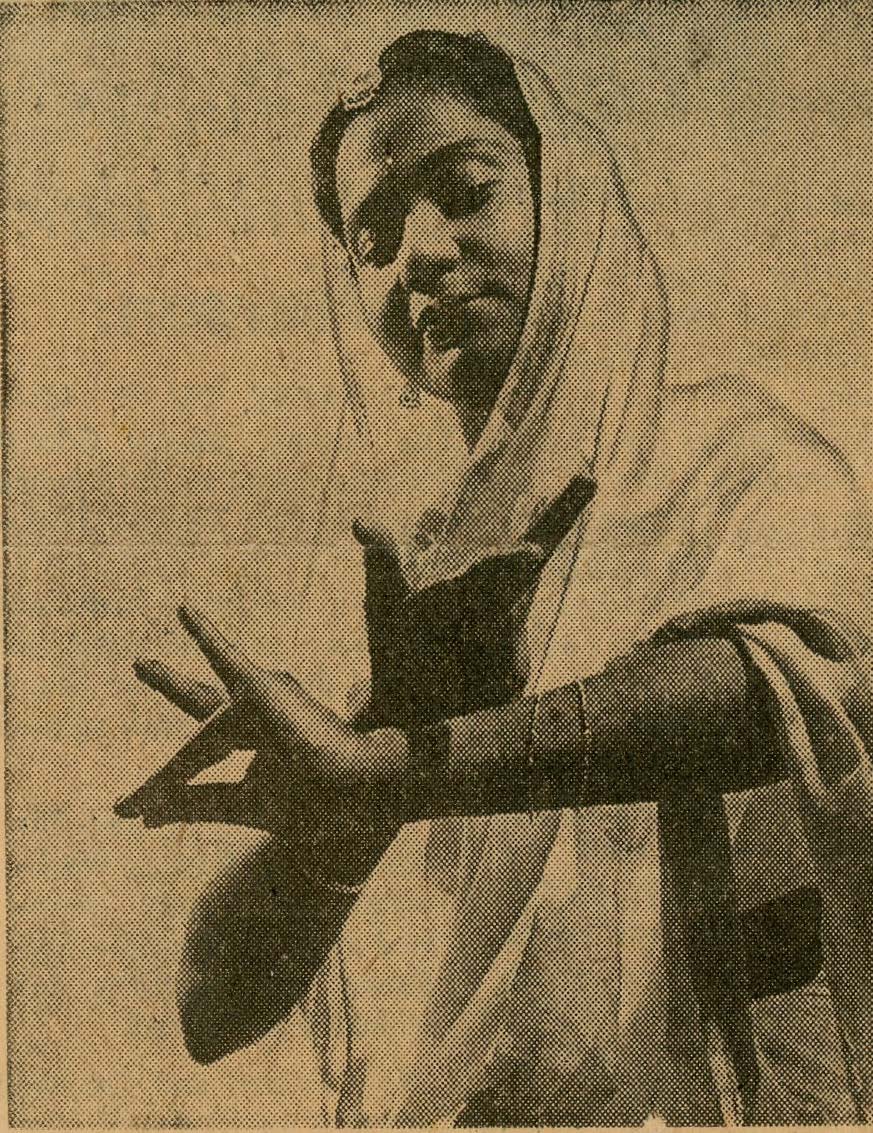

Edna Griffin, Civil Rights Activist

This post is the tenth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. This past summer, we have seen a nationwide movement for change. In Iowa City, Philadelphia, Chicago, Seattle,Continue reading “Edna Griffin, Civil Rights Activist”

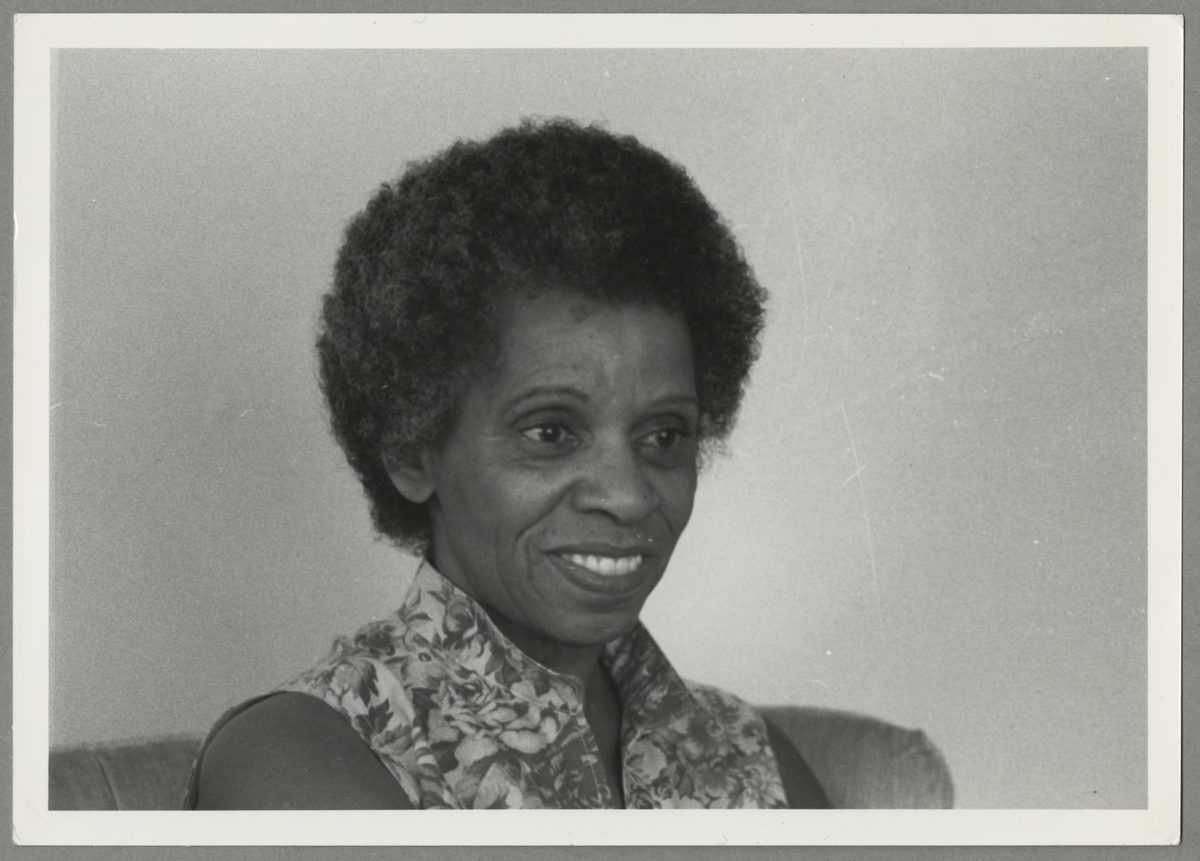

Pauline Humphrey & African American Beauty Culture in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the fifth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. Over the past few months, social media has been filled with peopleContinue reading “Pauline Humphrey & African American Beauty Culture in Iowa”