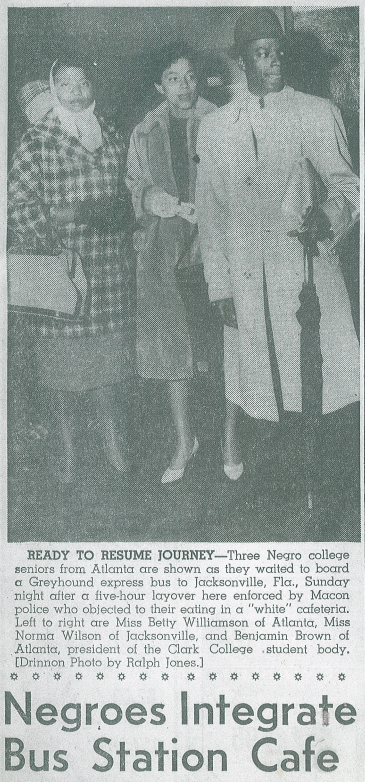

This post is by Archives Assistant Heather Cooper. The Iowa Women’s Archives recently received the first installment of a new collection of personal papers from Norma June Wilson Davis. Davis, who later became an administrator at the University of Iowa, was at the forefront of the student civil rights movement in Atlanta, Georgia, in theContinue reading “Civil Rights Trailblazer June Davis Donates Papers to IWA”

Tag Archives: Black History Month

Martha Nash: An Iowa Advocate for Black Voices

This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the fourth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series has run weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. The Martha Ann Furgerson Nash papers are filled with information about herContinue reading “Martha Nash: An Iowa Advocate for Black Voices”

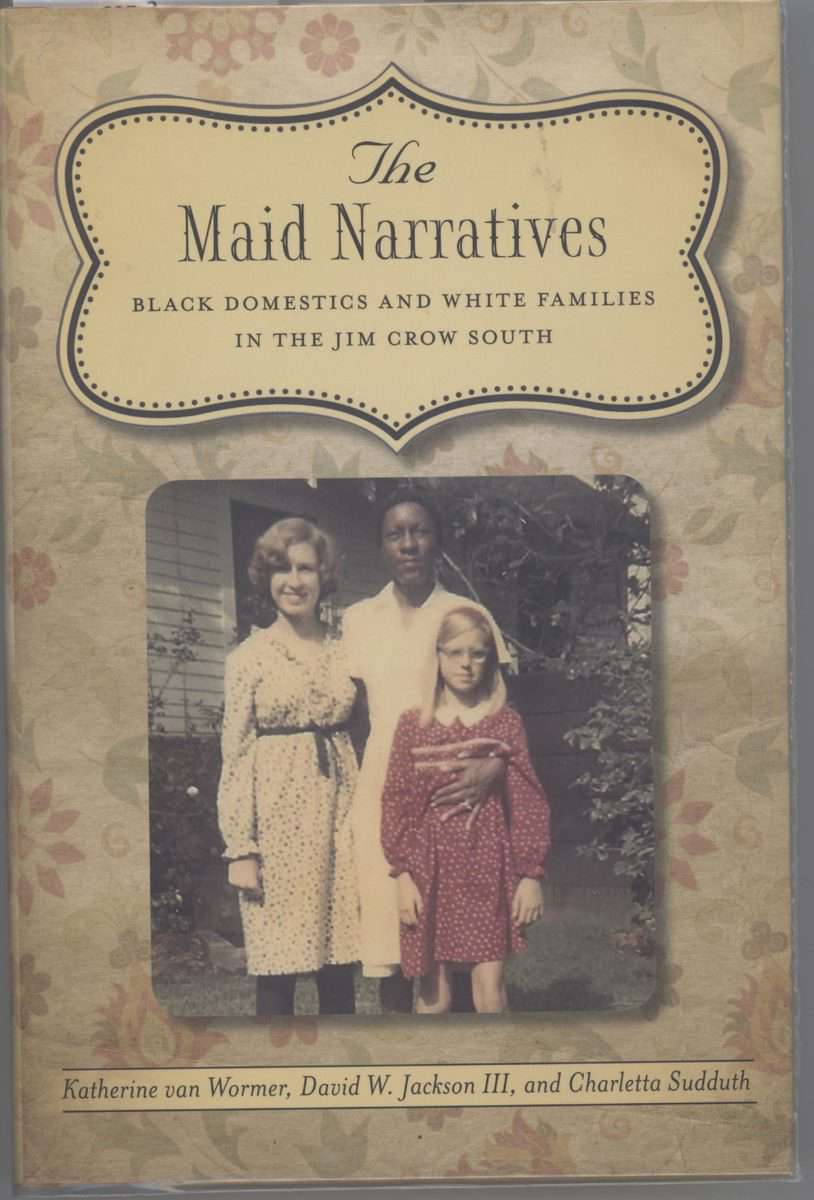

Iowa Women of the Great Migration: The Maid Narratives

This post by IWA Assistant Curator Janet Weaver and Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the second installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives’ collections. The series will continue weekly during Black History month, and monthly throughout 2020. The Iowa Women’s Archives is honored to be the repository forContinue reading “Iowa Women of the Great Migration: The Maid Narratives”

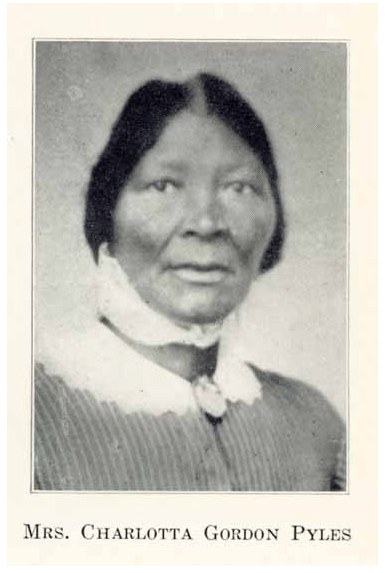

“The Desire for Freedom:” Early African American Settlers and Activists in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Assistant, Heather Cooper, is the first of a series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives’ collections. The series will continue weekly during Black History month, and monthly throughout 2020. The Grace Morris Allen Jones collection at the Iowa Women’s Archives consists of only one folder, but insideContinue reading ““The Desire for Freedom:” Early African American Settlers and Activists in Iowa”