The Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA) will kick off Women’s History Month with an event at the Iowa City Public Library! Welcoming the Immigrants: Refugee Resettlement in Jewish Iowa will bring Dr. Jeannette Gabriel of the Schwalb Center for Israel & Jewish Studies at theUniversity of Nebraska-Omaha to Iowa City. In her talk, Gabriel will useContinue reading “Kick off Women’s History Month with the Iowa Women’s Archives”

Category Archives: People

Community collaboration brings Latinx History from the archives to the classroom

This fall, Yamila Transtenvot, an instructor in Spanish at Cornell College, has been working with IWA, The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) Council 10, and the Davenport Community School District (DCSD) to bring primary sources about Latino/a/x history to Iowa schools. I sat down with Transtenvot this Latinx Heritage Month to discuss thisContinue reading “Community collaboration brings Latinx History from the archives to the classroom”

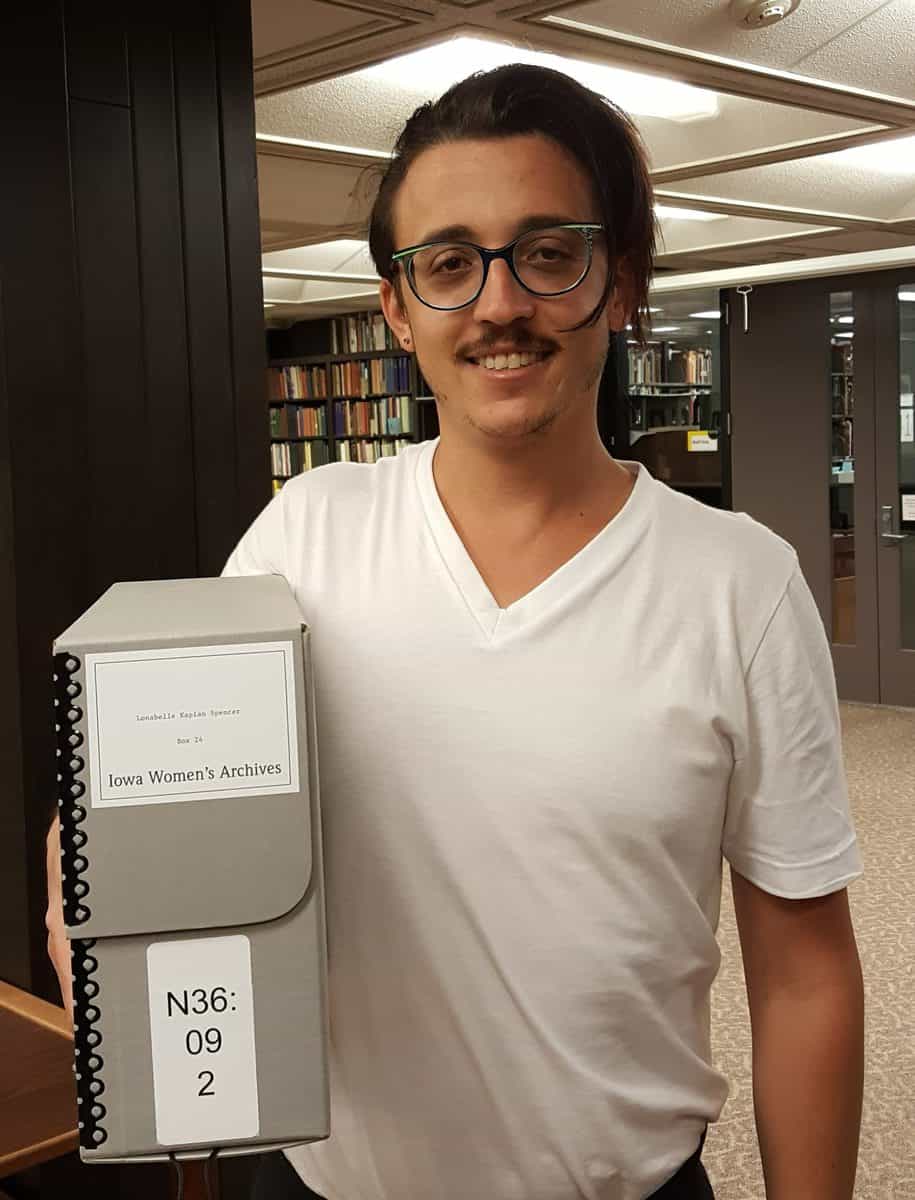

IWA’s 2021 Kerber Grant Recipient Finds Personal Stories within Industrial Agriculture

In Box 24 of the Lonabelle Kaplan Spencer papers, Andrew Seber finally found exactly what he was looking for: personal testimonies by rural citizens whose lives were turned upside down by the development of hog confinements near their Iowa homes. Seber’s dissertation, Neither Factory nor Farm: the Other Environmental Movement, will focus on industrial animalContinue reading “IWA’s 2021 Kerber Grant Recipient Finds Personal Stories within Industrial Agriculture”

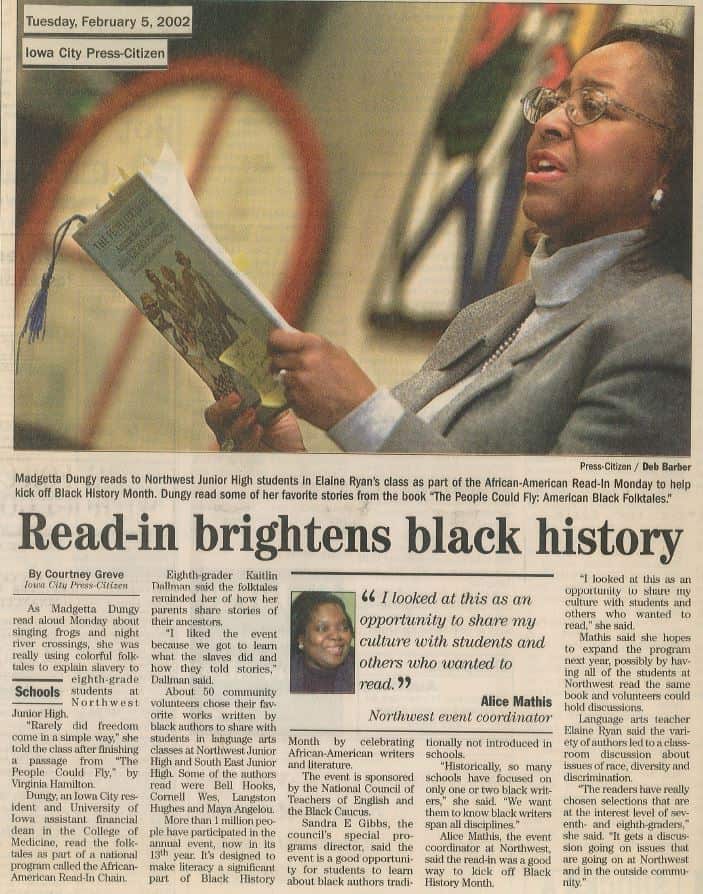

Student Reflection: Processing the Madgetta Dungy Papers

The following post is written by University of Iowa senior, Jack Kamp. When I started my internship at the Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA), I knew I was interested in working with Black women’s history. As a student interested in the history of civil rights and social justice, I knew that this collection would giveContinue reading “Student Reflection: Processing the Madgetta Dungy Papers”

Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader

This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the sixth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. Has anyone told you, you were going to be great in your youth?Continue reading “Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader”

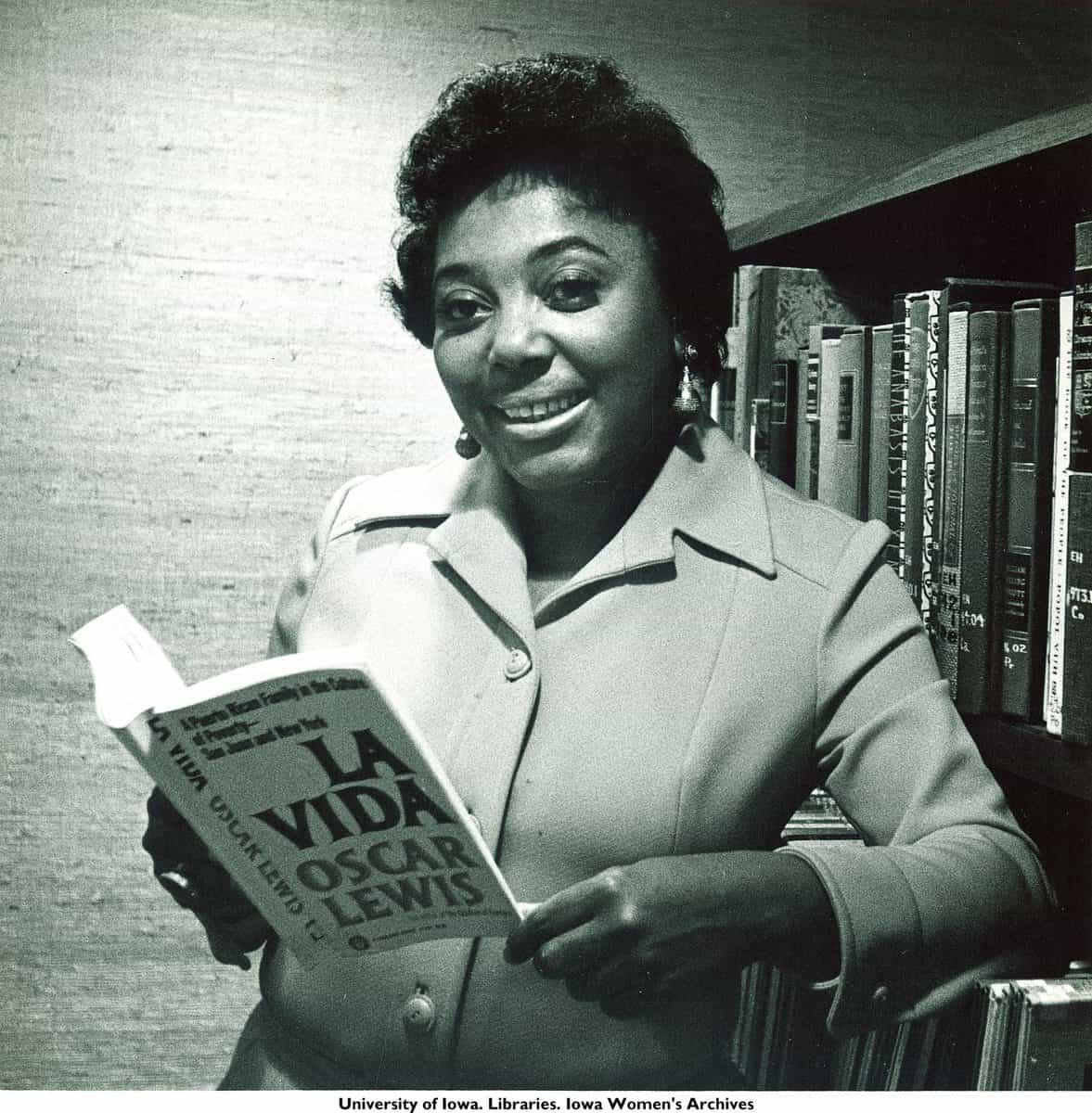

Martha Nash: An Iowa Advocate for Black Voices

This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the fourth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series has run weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. The Martha Ann Furgerson Nash papers are filled with information about herContinue reading “Martha Nash: An Iowa Advocate for Black Voices”

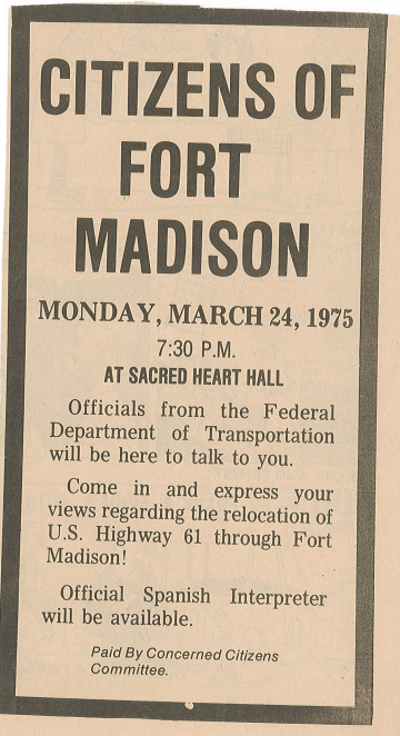

Virginia Harper and the Battle Against Highway 61

This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the third installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collection. The series will continue weekly during Black History Month, and monthly for the remainder of 2020. If you’re looking for a local history of civil rights activism, look noContinue reading “Virginia Harper and the Battle Against Highway 61”

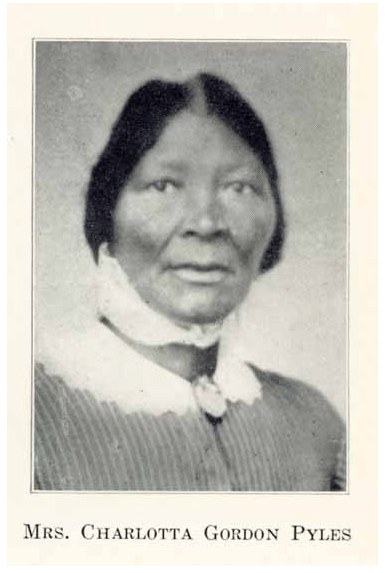

“The Desire for Freedom:” Early African American Settlers and Activists in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Assistant, Heather Cooper, is the first of a series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives’ collections. The series will continue weekly during Black History month, and monthly throughout 2020. The Grace Morris Allen Jones collection at the Iowa Women’s Archives consists of only one folder, but insideContinue reading ““The Desire for Freedom:” Early African American Settlers and Activists in Iowa”

Encountering Soul in the Iowa Women’s Archives: Scholar Taryn D. Jordan and the Aldeen Davis Papers

Taryn D. Jordan was researching Ella Fitzgerald at the Schlesinger Library in the Radcliffe Institute when she first encountered the papers that would bring her to the Iowa Women’s Archives. Jordan is a doctoral candidate in Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies at Emory University and an ACLS Mellon Dissertation Completion fellow who has been researchingContinue reading “Encountering Soul in the Iowa Women’s Archives: Scholar Taryn D. Jordan and the Aldeen Davis Papers”

History Reflected Back: Part II

Below is a reflection from Micaela Terronez, Olson Graduate Assistant, on a recent talk about her interest in the Mexican barrios of the Quad Cities at a local community gathering in Davenport, Iowa. She will be giving a version of this talk at “Workers’ Dream for an America that ‘Yet Must Be’ Struggles for Freedom and Dignity, Past andContinue reading “History Reflected Back: Part II”