Edna Griffin, known as the Rosa Parks of Iowa, has gained deserved attention over the years for her civil rights activism, especially for her role in the effort to desegregate the lunch counter at Katz Drug Store in Des Moines. Her actions resulted in a successful suit against the store under Iowa’s 1884 Civil RightsContinue reading “Kerber Grant Recipient’s Work Will Feature Political Activist Edna Griffin”

Category Archives: African American Women in Iowa

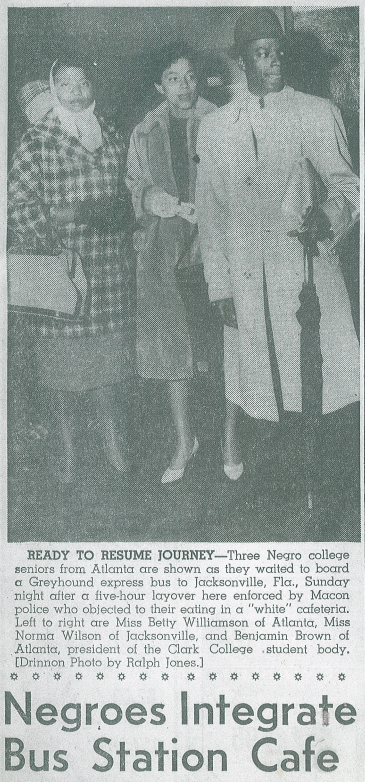

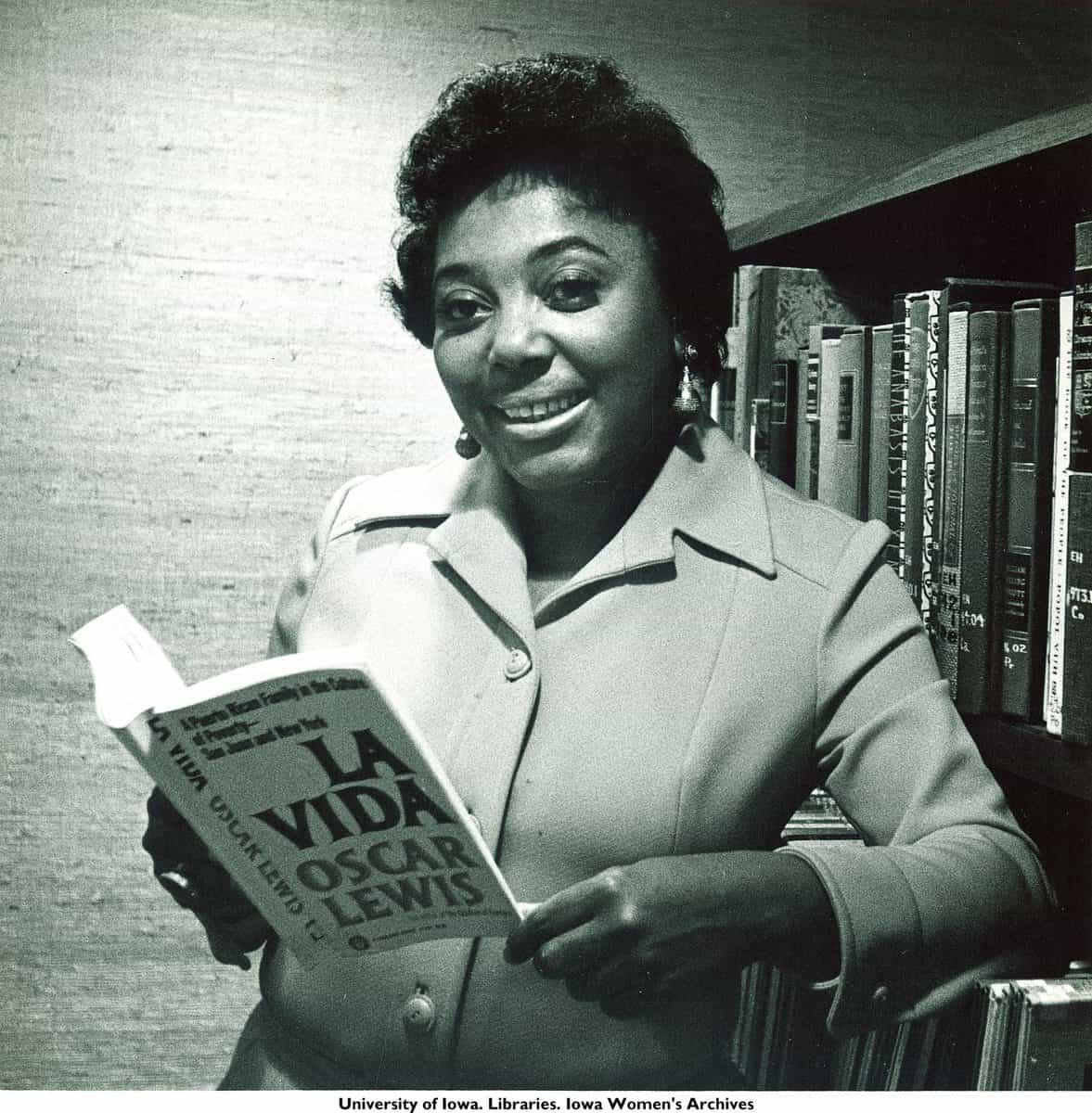

Civil Rights Trailblazer June Davis Donates Papers to IWA

This post is by Archives Assistant Heather Cooper. The Iowa Women’s Archives recently received the first installment of a new collection of personal papers from Norma June Wilson Davis. Davis, who later became an administrator at the University of Iowa, was at the forefront of the student civil rights movement in Atlanta, Georgia, in theContinue reading “Civil Rights Trailblazer June Davis Donates Papers to IWA”

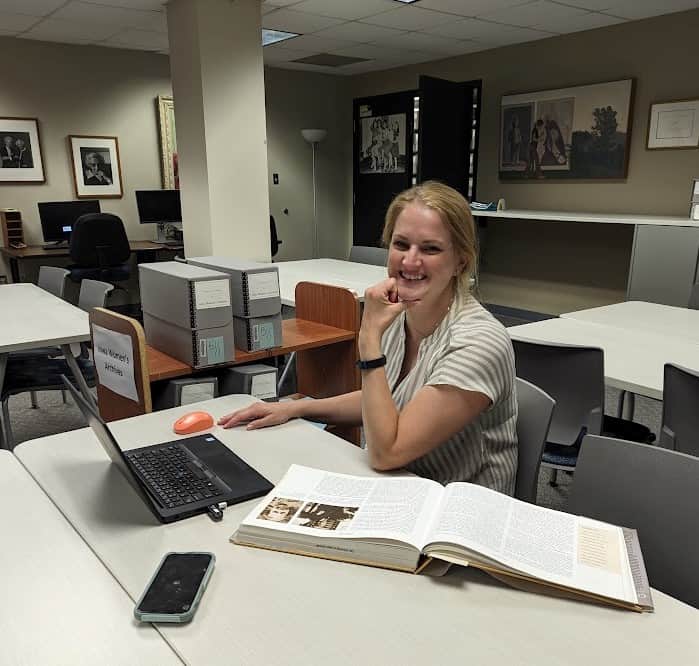

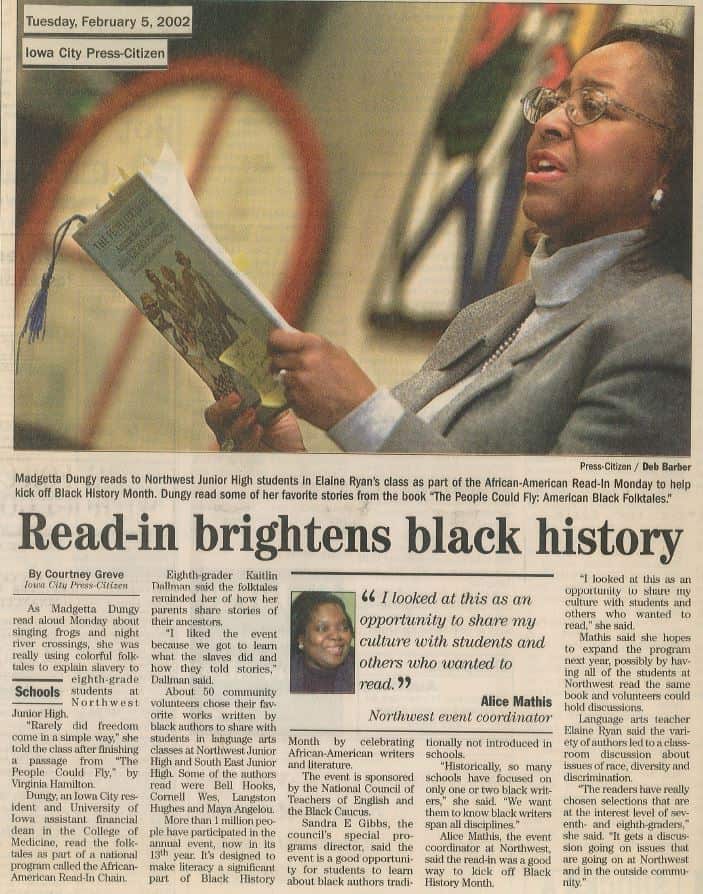

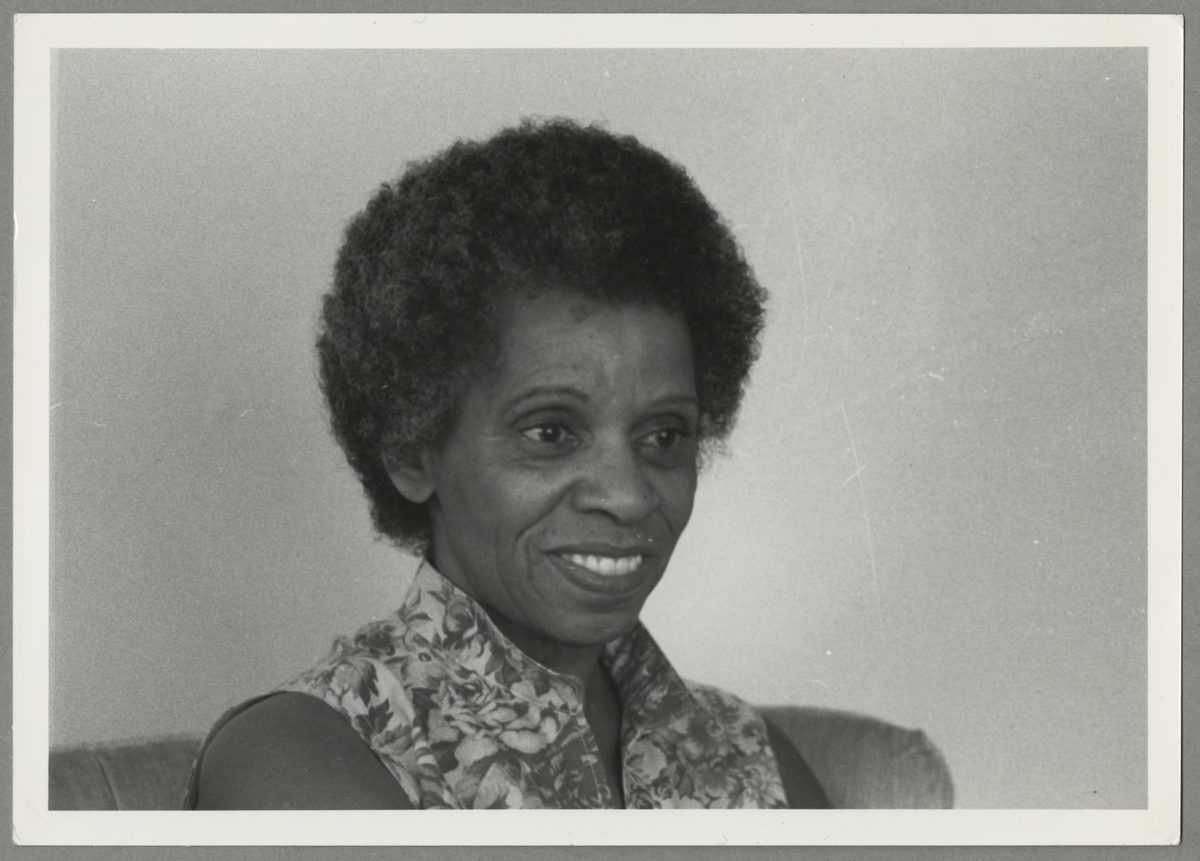

Student Reflection: Processing the Madgetta Dungy Papers

The following post is written by University of Iowa senior, Jack Kamp. When I started my internship at the Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA), I knew I was interested in working with Black women’s history. As a student interested in the history of civil rights and social justice, I knew that this collection would giveContinue reading “Student Reflection: Processing the Madgetta Dungy Papers”

Edna Griffin, Civil Rights Activist

This post is the tenth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. This past summer, we have seen a nationwide movement for change. In Iowa City, Philadelphia, Chicago, Seattle,Continue reading “Edna Griffin, Civil Rights Activist”

From Alabama to the Barrio: Ernest Rodriguez and the Fight Against Racism in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the ninth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. In honor of Latinx Heritage Month (September 15 – OctoberContinue reading “From Alabama to the Barrio: Ernest Rodriguez and the Fight Against Racism in Iowa”

Reuben Gaines Memoir of Being Black in Buxton, Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Assistant, Erik Henderson, is the eighth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. The once prosperous coal mining town, Buxton, Iowa, approximately thirty minutes southwest of OskaloosaContinue reading “Reuben Gaines Memoir of Being Black in Buxton, Iowa”

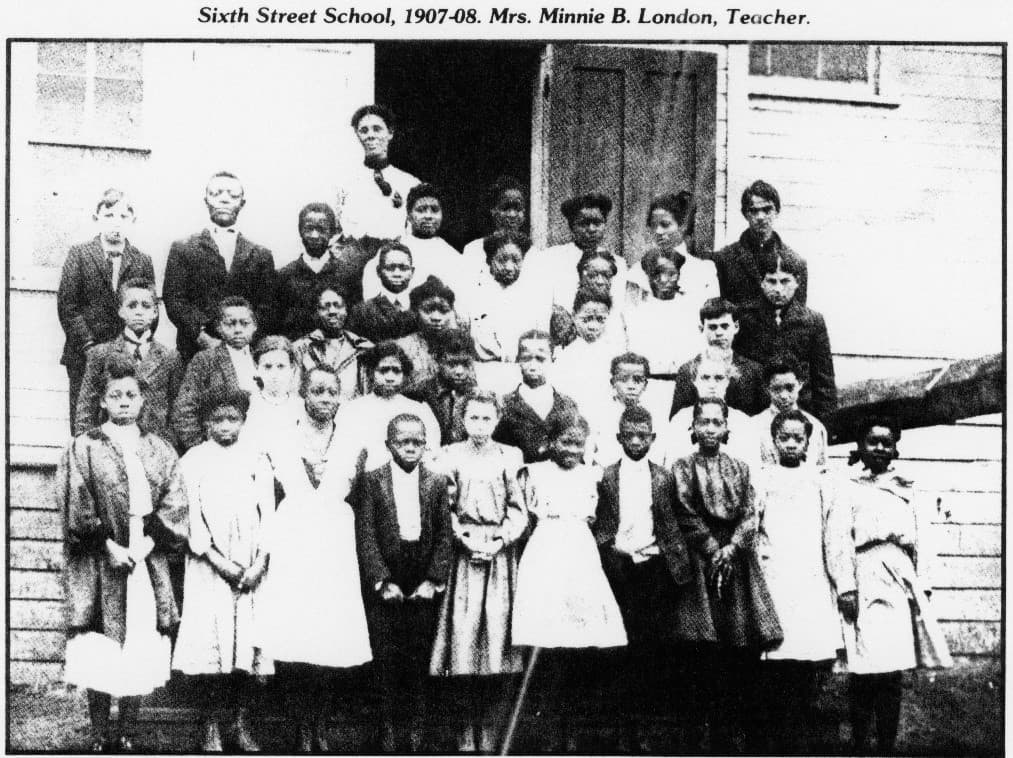

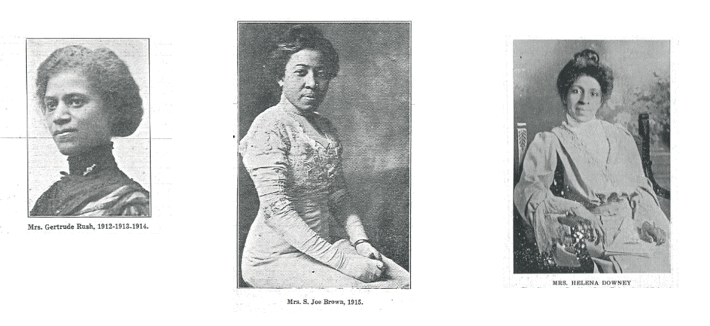

Before the Vote: Black Women’s Political Activism in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the seventh installment in our series highlighting African American history in the collections of Iowa Women’s Archives and other local repositories. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. The State Historical Society of Iowa holdsContinue reading “Before the Vote: Black Women’s Political Activism in Iowa”

Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader

This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the sixth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. Has anyone told you, you were going to be great in your youth?Continue reading “Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader”

Pauline Humphrey & African American Beauty Culture in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the fifth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. Over the past few months, social media has been filled with peopleContinue reading “Pauline Humphrey & African American Beauty Culture in Iowa”

Martha Nash: An Iowa Advocate for Black Voices

This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the fourth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series has run weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. The Martha Ann Furgerson Nash papers are filled with information about herContinue reading “Martha Nash: An Iowa Advocate for Black Voices”