In 1930, the Stratemeyer Syndicate published the first Nancy Drew mystery, The Secret of the Old Clock by Carolyn Keene. Since then, Nancy Drew has become known around the world. But who was behind Carolyn Keene? The mystery of the pseudonym persisted until a 1980 court case identified Mildred Wirt Benson, a journalist and IowaContinue reading “New Website Celebrates Mildred Wirt Benson, the First Carolyn Keene”

Category Archives: In the news

25 for 25: Ernest Rodriguez and Estefania Rodriguez

Ernest and Estefania Rodriguez’s father, Norberto, migrated to the United States from the state of Jalisco, Mexico in 1910. He met their mother, Muggie Adams, an African-American woman from Alabama in Iowa. The Rodriguez family lived in Holy City, a box car community in Bettendorf, Iowa for several years, and Ernest and Estefania both workedContinue reading “25 for 25: Ernest Rodriguez and Estefania Rodriguez”

Janet Weaver wins 2017 ACRL WGSS Significant Achievement Award

via Association of College and Research Libraries: http://www.ala.org/news/member-news/2017/02/weaver-wins-2017-acrl-wgss-significant-achievement-award CHICAGO – Janet Weaver, assistant curator of the Iowa Women’s Archives at the University of Iowa, is the winner of the 2017 Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) Women and Gender Studies Section (WGSS) Award for Significant Achievement in Woman’s Studies Librarianship. The WGSS award honorsContinue reading “Janet Weaver wins 2017 ACRL WGSS Significant Achievement Award”

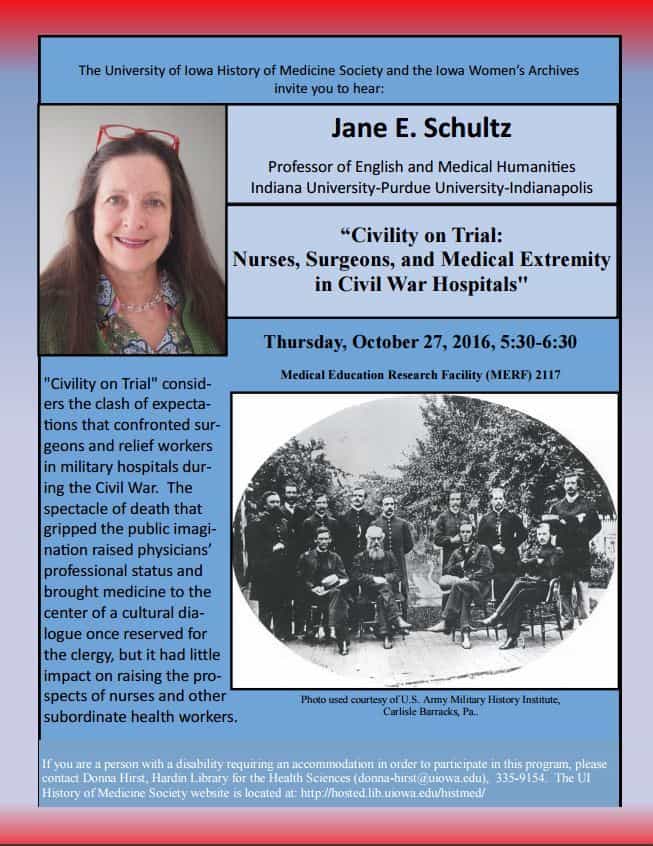

Do Not Miss Three Events from October 24th – 27th

From October 24th – 27th Trudy Huskamp Peterson, the former Acting Archivist of the United States, and Jane E. Schultz, Professor of English and Medical Humanities at Indiana University-Purdue University-Indianapolis, will visit the University of Iowa. A longtime friend of the Iowa Women’s Archives, Trudy Huskamp Peterson has made an international career of archives andContinue reading “Do Not Miss Three Events from October 24th – 27th”

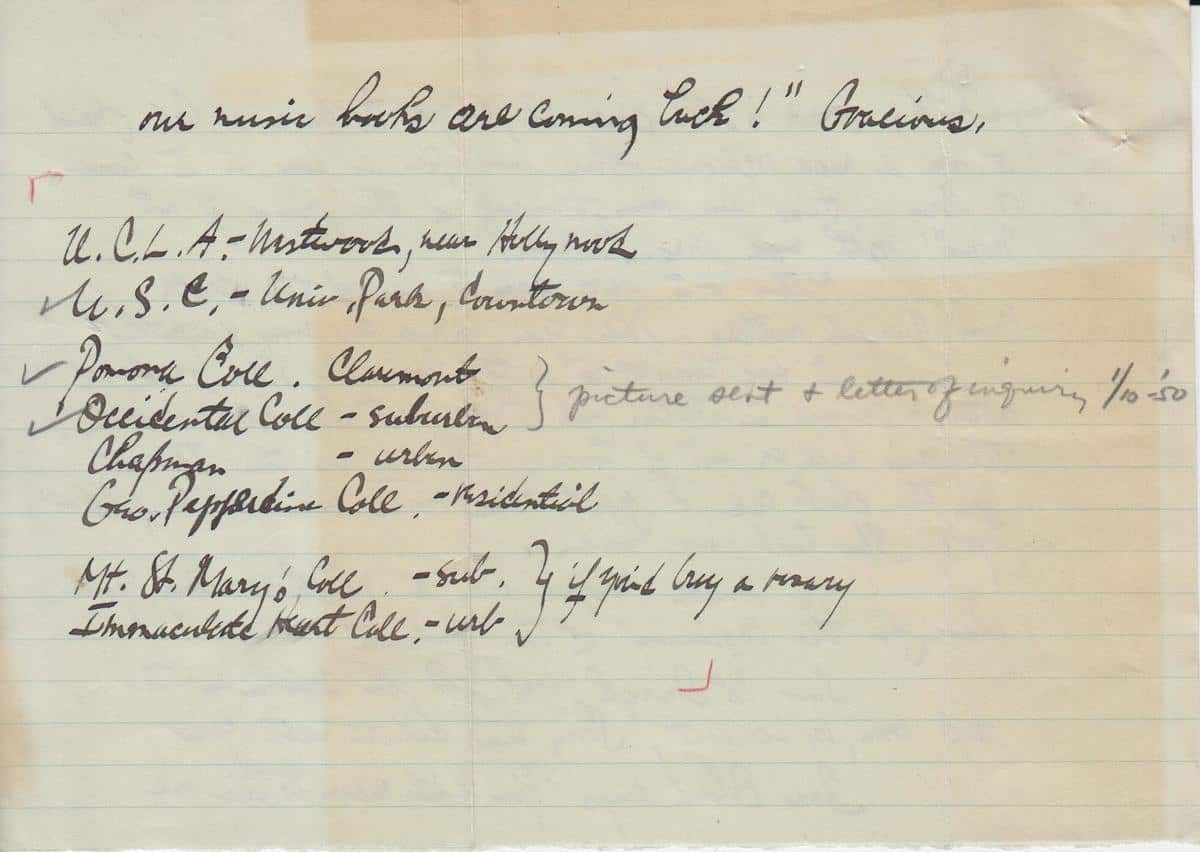

Dr. Dorothy Wirtz, PhD: A Woman “In the Profession”

“Gentlemen, As you had hoped, I have found your questionnaire interesting to answer. However, I cannot refrain from expressing my resentment at the phrasing of certain statements, which seem to me to reflect discrimination on the basis of sex.” So begins Dr. Dorothy Wirtz’s 1969 letter to The Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. She followedContinue reading “Dr. Dorothy Wirtz, PhD: A Woman “In the Profession””

Calling All Sleuths! 2015 Nancy Drew Iowa Convention

University of Iowa Libraries, Special Collections Dept. Come check out the 2015 Nancy Drew Iowa Convention, celebrating the 85th anniversary of Nancy Drew and the 110th anniversary of Iowa native and Nancy Drew author, Mildred Wirt Benson! 9:30am, Friday, May 1 University of Iowa Main Library, Room 2032. This event is free and open toContinue reading “Calling All Sleuths! 2015 Nancy Drew Iowa Convention”

Louise Liers, World War I nurse

This post, by Christina Jensen, appeared on the Iowa Women’s Archives Tumblr this summer, and has since been featured on NBC news. On June 28th, 1914, Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo by Yugoslav nationalist Gavrilo Princip. One month later, war broke out across Europe between two alliance systems. Britain, France, Russia, andContinue reading “Louise Liers, World War I nurse”

Remembering Emma’s early days

This post was written by Jessica Lawson, Graduate Research Assistant in the Iowa Women’s Archives. The Iowa Women’s Archives had an exciting visit at the end of July! Five women who were active in the feminist community in Iowa City in the 1970s and were early supporters of the Emma Goldman Clinic for Women visited theContinue reading “Remembering Emma’s early days”

Nineteenth Century Davenport as a Hotbed of Controversial Alternative Medicine Schools

The University of Iowa History of Medicine Society & the Iowa Women’s Archives invite you to: Nineteenth Century Davenport as a Hotbed of Controversial Alternative Medicine Schools Featuring Greta Nettleton, University of Iowa author and historian Thursday June 19, 2014, 5:30-6:30 PM MERF Room 2117 (Medical Education and Research Facility across from Hardin Library) Mrs. Dr.Continue reading “Nineteenth Century Davenport as a Hotbed of Controversial Alternative Medicine Schools”

Archives Alive!: Teaching with WWII Correspondence

This post was originally written by Jen Wolfe, Digital Scholarship Librarian, for the UI Libraries Digital Research & Publishing Blog. It is re-posted here with minor modifications. University of Iowa faculty, students, and staff discussed a curriculum project that combines historic documents with digital tools and methods as part of the Irving B. Weber Days local historyContinue reading “Archives Alive!: Teaching with WWII Correspondence”