by Beatrice Kearns, graduate assistant, Iowa Women’s Archives The University of Iowa Dental Hygiene Program began in 1953 with 24 students and despite being nationally renowned, the female-dominated program did not make it to its 50th anniversary. Until the final graduating class in 1995, the program trained hundreds of hygienists. Students took classes in aContinue reading “Done biting their tongues: UI dental hygiene and gender discrimination”

Tag Archives: university of Iowa

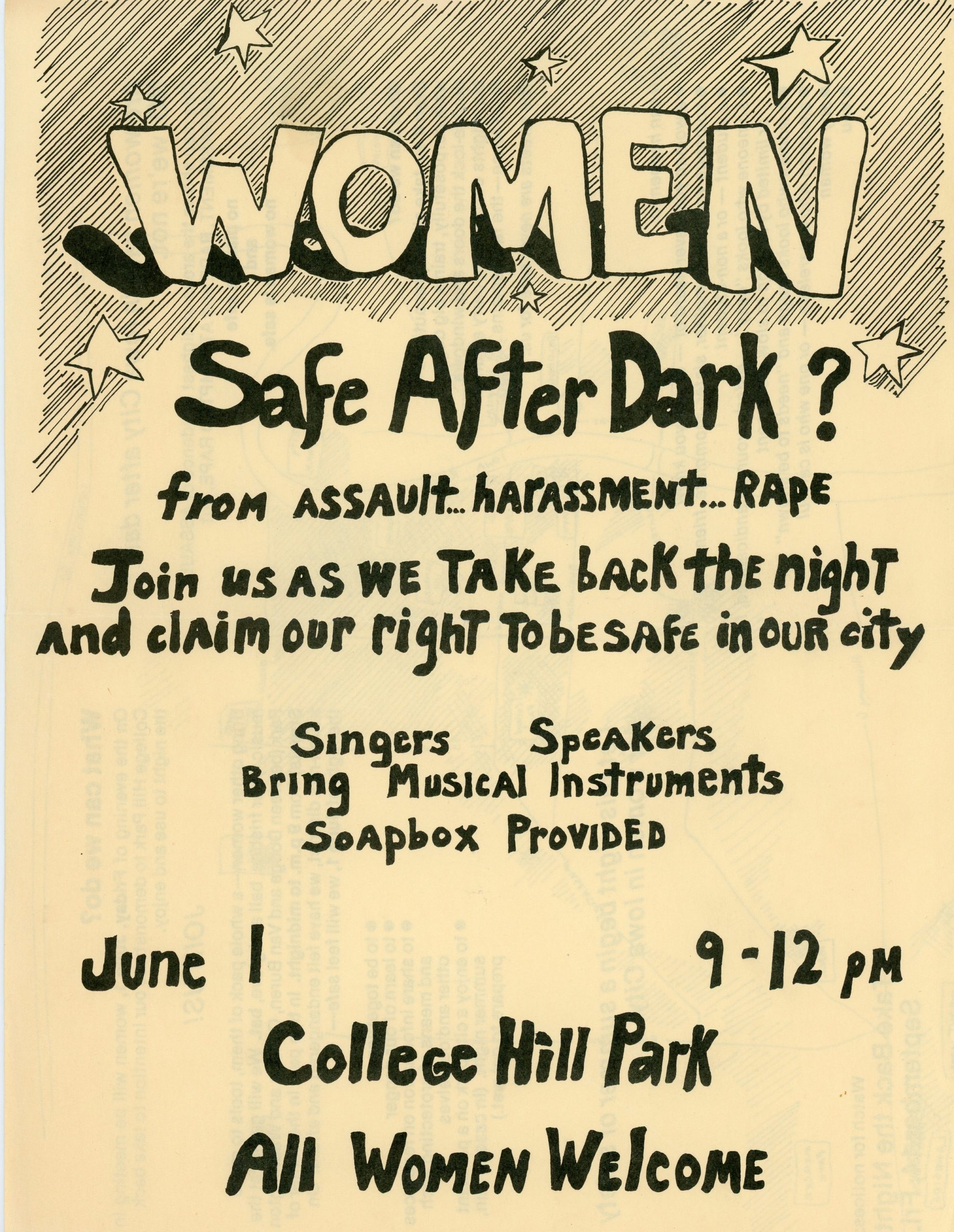

Women Safe After Dark? The Beginnings of Take Back the Night at the University of Iowa

On September 12, 1979, an advertisement for a rally appeared in the campus newspaper, the Daily Iowan. The outline of a woman with bows and arrows, shooting into the night sky was accompanied with the promise, “Friday evening at 8 p.m., the women of Iowa City will have a chance to support each other inContinue reading “Women Safe After Dark? The Beginnings of Take Back the Night at the University of Iowa”

Kittredge Cherry and Audrey Lockwood: A Love Story

This post was written by IWA Student Specialist, Abbie Steuhm. The LGBTQ+ community has grown in incredible size and visibility in the last decade. The legalization of same-sex marriage in the U.S. in 2015 was a colossal milestone for LGBTQ+ rights, and it has arguably helped in the normalization and acceptance of LGBTQ+ people nationwide.Continue reading “Kittredge Cherry and Audrey Lockwood: A Love Story”

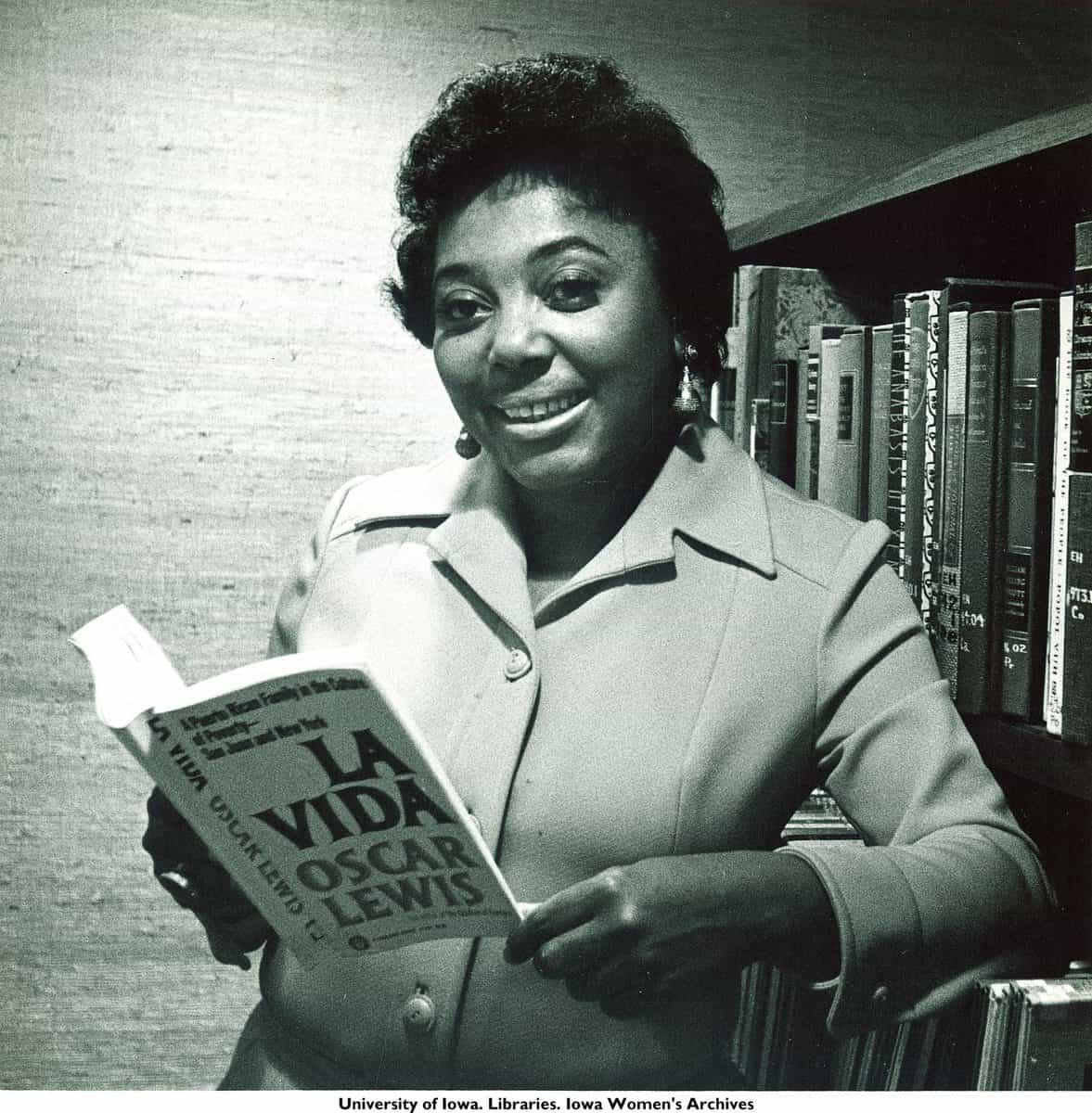

Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader

This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the sixth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. Has anyone told you, you were going to be great in your youth?Continue reading “Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader”

Black History Month: African American Women at University of Iowa

Photos of Adah Hyde Johnson (1912), Dora Martin Berry (1956), and students in the newly integrated Currier Hall (1946). Though the University of Iowa was one of the first institutions to open admission to African Americans, these students often had to overcome other barriers to an equal education. Our digital collection on African American Women StudentsContinue reading “Black History Month: African American Women at University of Iowa”