The following post was written by IWA Student Assistant, Abbie Steuhm.

The Disability Rights Movement has seen great progress and recognition in recent years; however, as with most social movements, the historic past for disabled people is one of severe discrimination and offensive, prejudiced, and even racist language.

On January 30, 1972, Anthony Shaw, M.D. published an article titled “’Doctor, Do We Have a Choice?’” in The New York Times, where he discussed guiding parents in their decision about whether to allow their infant born with Down Syndrome to have life-saving surgery, or to let them die. In his article, Shaw shares how he knew many other physicians who were parents of children with Down Syndrome and how “almost all have placed them in institutions,” remarking that “couples who are success-oriented and have high expectations for their children are likely to institutionalize their mentally deficient offspring rather than keep them at home.” Shaw continues his prejudiced commentary by adding that “although most parents allow the necessary surgery, many of them would be relieved to have their [child] die.”

However, through scouring the IWA, a common thread in history can be found: if there is a public forum, people will use it to express their own beliefs. Which is exactly what happened with Shaw’s New York Times article. Social workers, employees of state health departments, and average people wrote to the editor to address Shaw’s disturbing prejudices with their own life experiences.

Mrs. Ethel H. Basch, a social worker and mother of a child with Down Syndrome, replied, “Some of the things that Dr. Anthony Shaw said… made me hopping mad… It has been my experience that the physician is the last one to offer supportive help for the parents of defective children…”

Dennis R. Ferguson, an employee of the Connecticut State Department of Health, replied, “I draw a very distinct difference between abortions and postnatal euthanasia. I cannot accept Dr. Shaw’s posture that parents of handicapped children have the legal and/or moral responsibility of determining whether this human being lives or dies.”

Shaw’s article may appear as an oddity considering its placement within the Elizabeth D. Riesz papers. Elizabeth Riesz, born 1937, was a teacher, educational consultant, and advocate for services for disabled people. Her own daughter Sarah, born 1972, had Down Syndrome, which made Riesz realize how little resources there were for parents of children with Down Syndrome. Instead of following Shaw’s statement on placing children in an institution, Riesz raised Sarah at home. Sarah would later be among the first students with disabilities to be integrated into the Iowa City public school system.

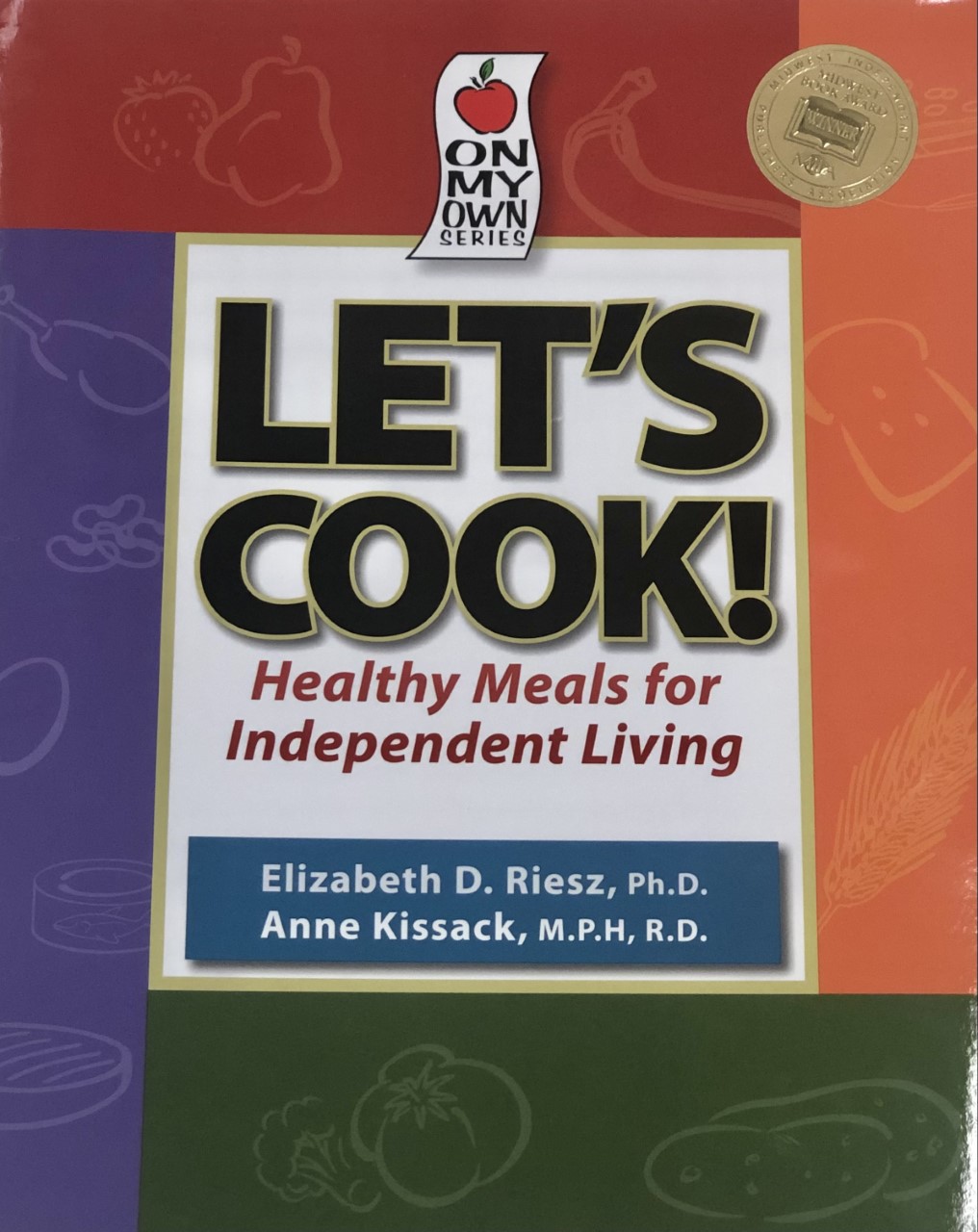

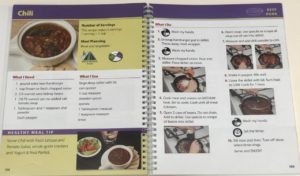

Elizabeth Riesz would continue her advocacy, becoming the president of the Association for Retarded Citizens (ARC) of Johnson County (1977-1982) and traveling to Osaka, Japan to speak about disability resources and programs, with some of those programs being implemented in Japanese schools. Riesz would also go on to create the Let’s Cook!: Healthy Meals for Independent Living cookbook. This cookbook, designed for people with disabilities who live independently, gives a variety of nutritious recipes from Apricot Curry Chicken to Smothered Porkchops, along with clear instructions, large photo illustrations, and meal planning and preparation advice. In the cookbook’s introduction, Riesz shared how her daughter had three heart problems along with Down syndrome “that caused her to grow slowly and left her physically weak.” But Sarah grew up strong and healthy, and in her teenage years, Riesz and Sarah’s father “loved coming home from work on Mondays! That’s the day of the week that Sarah cooked… for our family.” Sarah’s recipes would become the foundation for the cookbook, and her meals are eaten and loved by many.

So, why would one find Shaw within Riesz’s collection of achievements and work for disability rights? Shaw’s article was published in 1972, the same year Sarah Riesz was born. Instead of finding resources, programs, and a supportive community for her newborn daughter, Elizabeth Riesz instead found an article published in a popular newspaper from a doctor tasked with performing surgeries on children like Sarah, discussing his encouragement of parents to euthanize their children born with Down Syndrome, as the only other supposed option was institutionalizing the child. Faced with such heavy-handed discrimination from the very people who are supposed to help save children like Sarah, Riesz went against all odds and created her own programs and resources. Riesz raised her daughter at home, supporting her throughout her life. Riesz then shared her achievements with those in Iowa City and even Japan. Shaw’s article serves as evidence to what disabled people faced within the medical system and their daily lives. Elizabeth and Sarah Riesz are truly inspirational for not only proving Shaw incredibly wrong, but also working to improve their own lives and the lives of disabled people during a time where disabilities were grounds for death.