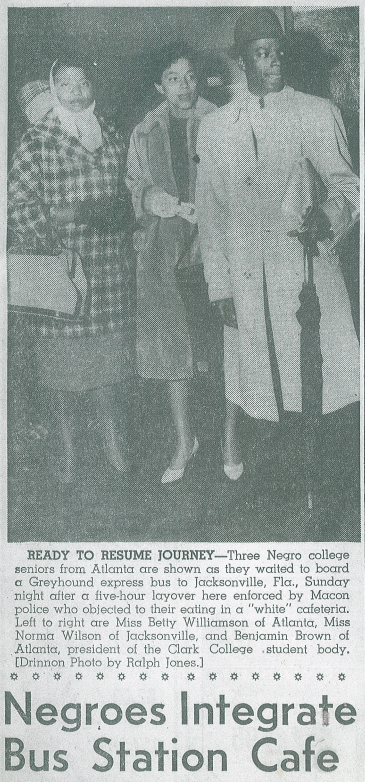

This post is by Archives Assistant Heather Cooper. The Iowa Women’s Archives recently received the first installment of a new collection of personal papers from Norma June Wilson Davis. Davis, who later became an administrator at the University of Iowa, was at the forefront of the student civil rights movement in Atlanta, Georgia, in theContinue reading “Civil Rights Trailblazer June Davis Donates Papers to IWA”

Tag Archives: Heather Cooper

From Alabama to the Barrio: Ernest Rodriguez and the Fight Against Racism in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the ninth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. In honor of Latinx Heritage Month (September 15 – OctoberContinue reading “From Alabama to the Barrio: Ernest Rodriguez and the Fight Against Racism in Iowa”

Pauline Humphrey & African American Beauty Culture in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the fifth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. Over the past few months, social media has been filled with peopleContinue reading “Pauline Humphrey & African American Beauty Culture in Iowa”

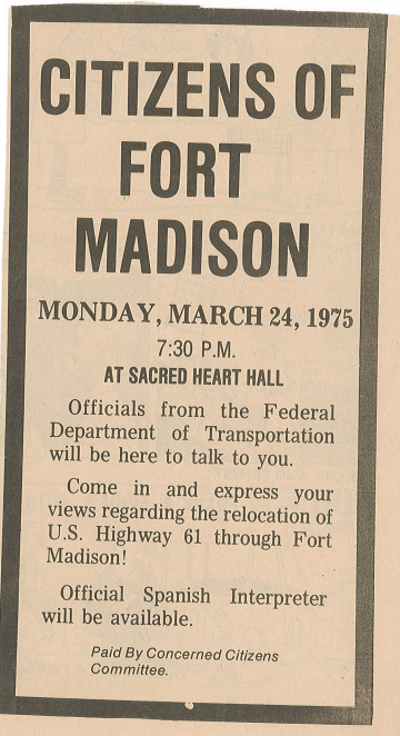

Virginia Harper and the Battle Against Highway 61

This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the third installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collection. The series will continue weekly during Black History Month, and monthly for the remainder of 2020. If you’re looking for a local history of civil rights activism, look noContinue reading “Virginia Harper and the Battle Against Highway 61”

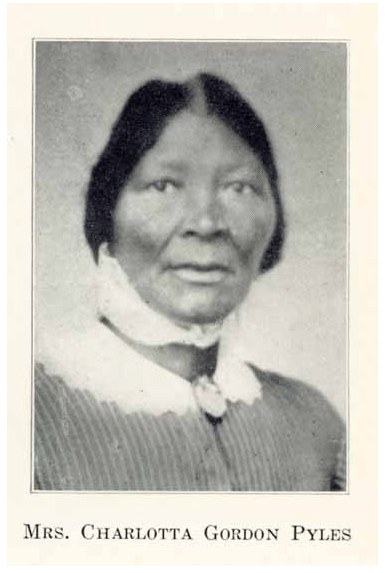

“The Desire for Freedom:” Early African American Settlers and Activists in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Assistant, Heather Cooper, is the first of a series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives’ collections. The series will continue weekly during Black History month, and monthly throughout 2020. The Grace Morris Allen Jones collection at the Iowa Women’s Archives consists of only one folder, but insideContinue reading ““The Desire for Freedom:” Early African American Settlers and Activists in Iowa”

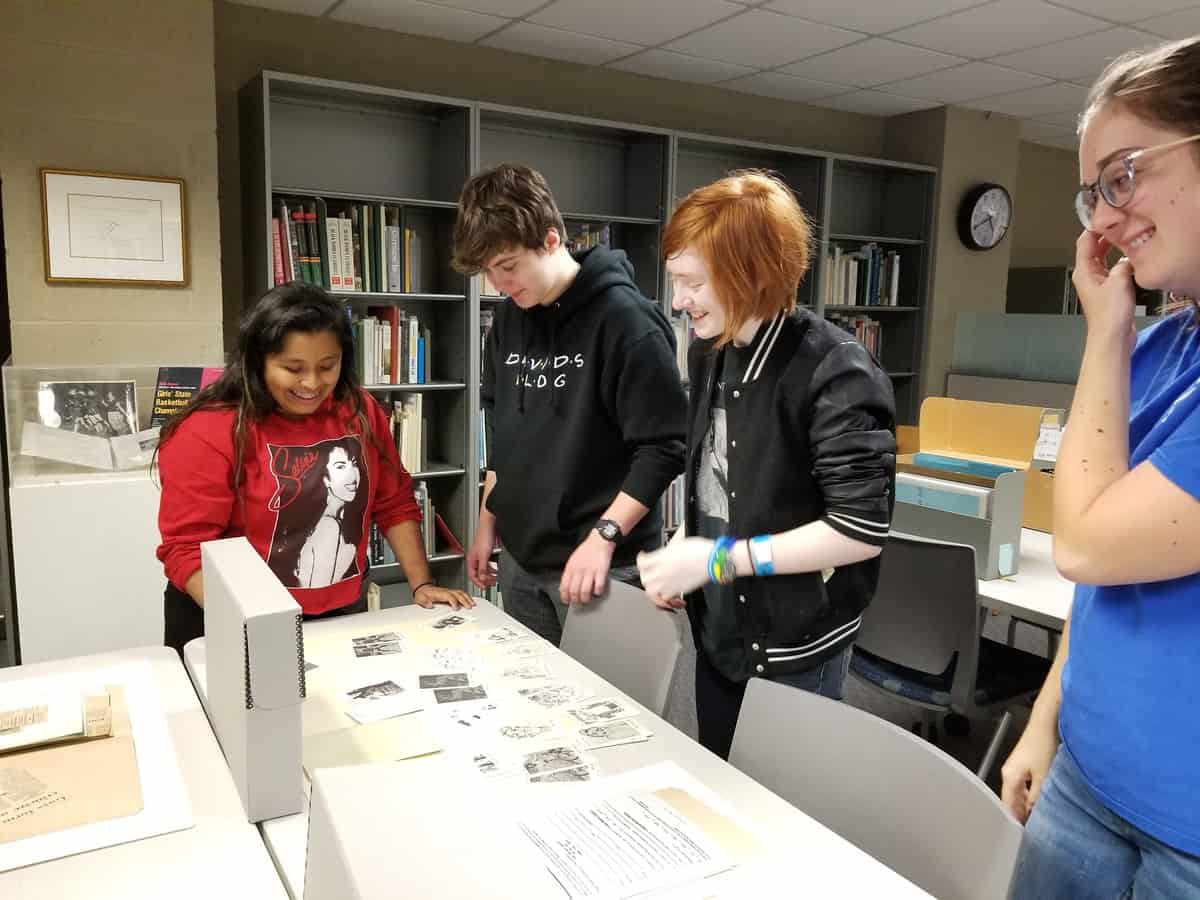

Activists in the Archives: Connecting High School Students with Local LGBTQ History

Guest post by Dr. Heather Cooper, Visiting Assistant Professor in History and Gender, Women’s, and Sexuality Studies During LGBTQ History Month in October 2018, I worked with the Iowa Women’s Archives and University Special Collections to organize an archives visit for students from West Liberty High School. The several students who were able to attendContinue reading “Activists in the Archives: Connecting High School Students with Local LGBTQ History”