This post was written by IWA Student Specialist, Abbie Steuhm. The LGBTQ+ community has grown in incredible size and visibility in the last decade. The legalization of same-sex marriage in the U.S. in 2015 was a colossal milestone for LGBTQ+ rights, and it has arguably helped in the normalization and acceptance of LGBTQ+ people nationwide.Continue reading “Kittredge Cherry and Audrey Lockwood: A Love Story”

Category Archives: Women’s History Month

Kick off Women’s History Month with the Iowa Women’s Archives

The Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA) will kick off Women’s History Month with an event at the Iowa City Public Library! Welcoming the Immigrants: Refugee Resettlement in Jewish Iowa will bring Dr. Jeannette Gabriel of the Schwalb Center for Israel & Jewish Studies at theUniversity of Nebraska-Omaha to Iowa City. In her talk, Gabriel will useContinue reading “Kick off Women’s History Month with the Iowa Women’s Archives”

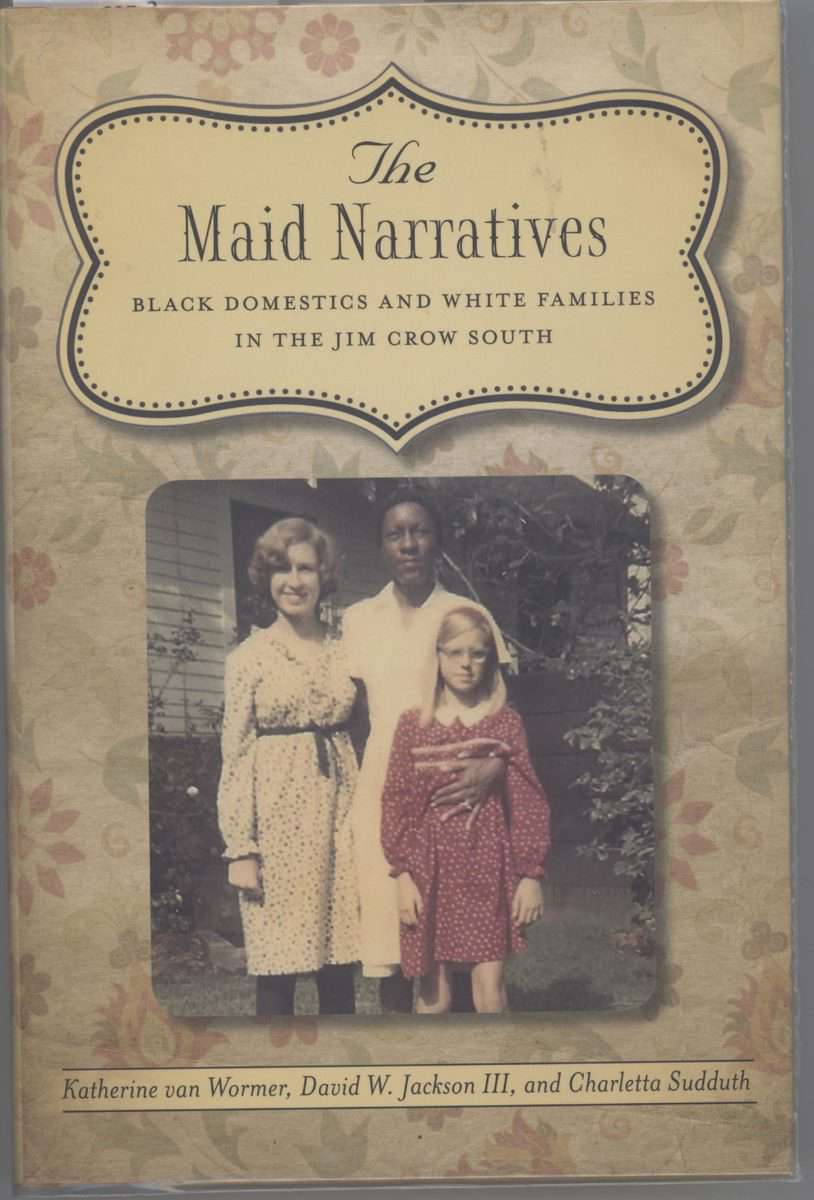

Iowa Women of the Great Migration: The Maid Narratives

This post by IWA Assistant Curator Janet Weaver and Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the second installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives’ collections. The series will continue weekly during Black History month, and monthly throughout 2020. The Iowa Women’s Archives is honored to be the repository forContinue reading “Iowa Women of the Great Migration: The Maid Narratives”

Playing, Pretending, Becoming: Iowa Girls and Their Dolls

Shirley Briggs had a lot of toys. As a very little girl in the early 1920s, Shirley had dozens of pictures taken of her ensconced in an oversized chair with children’s book, playing in a wheel barrow, sitting in the sun, all with a coterie of stuffed animals and dolls. The most frequent companion, andContinue reading “Playing, Pretending, Becoming: Iowa Girls and Their Dolls”

History Reflected Back: Part II

Below is a reflection from Micaela Terronez, Olson Graduate Assistant, on a recent talk about her interest in the Mexican barrios of the Quad Cities at a local community gathering in Davenport, Iowa. She will be giving a version of this talk at “Workers’ Dream for an America that ‘Yet Must Be’ Struggles for Freedom and Dignity, Past andContinue reading “History Reflected Back: Part II”

History Reflected Back: Part I

Below is a reflection from Micaela Terronez, Olson Graduate Assistant, on a recent talk about her interest in the Mexican barrios of the Quad Cities at a local community gathering in Davenport, Iowa. She will be giving a version of this talk at “Workers’ Dream for an America that ‘Yet Must Be’ Struggles for Freedom and Dignity, Past andContinue reading “History Reflected Back: Part I”

International Women’s Day

I am sister, I am daughter, I am mother, I am wife. I am all the women in my lineage, their triumphs and mistakes my birthright. This post and poem were written by Zayetzy Luna Garcia, student worker at the Iowa Women’s Archives Family unity is the center of Latinx culture. It is ourContinue reading “International Women’s Day”

Dr. Dorothy Wirtz, PhD: A Woman “In the Profession”

“Gentlemen, As you had hoped, I have found your questionnaire interesting to answer. However, I cannot refrain from expressing my resentment at the phrasing of certain statements, which seem to me to reflect discrimination on the basis of sex.” So begins Dr. Dorothy Wirtz’s 1969 letter to The Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. She followedContinue reading “Dr. Dorothy Wirtz, PhD: A Woman “In the Profession””

Public Talk March 24, 2016 at 4:00PM “Jewish Women and Community Life in Iowa”

WE DID SO MUCH BEYOND THE HOME JEWISH WOMEN AND COMMUNITY LIFE IN IOWA A talk by Jeannette Gabriel, Graduate Research Assistant, Jewish Women in Iowa Project, Iowa Women’s Archives Join us to hear the untold stories of Jewish women’s involvement in community activities throughout Iowa history, whether in cities with robust Jewish populationsContinue reading “Public Talk March 24, 2016 at 4:00PM “Jewish Women and Community Life in Iowa””

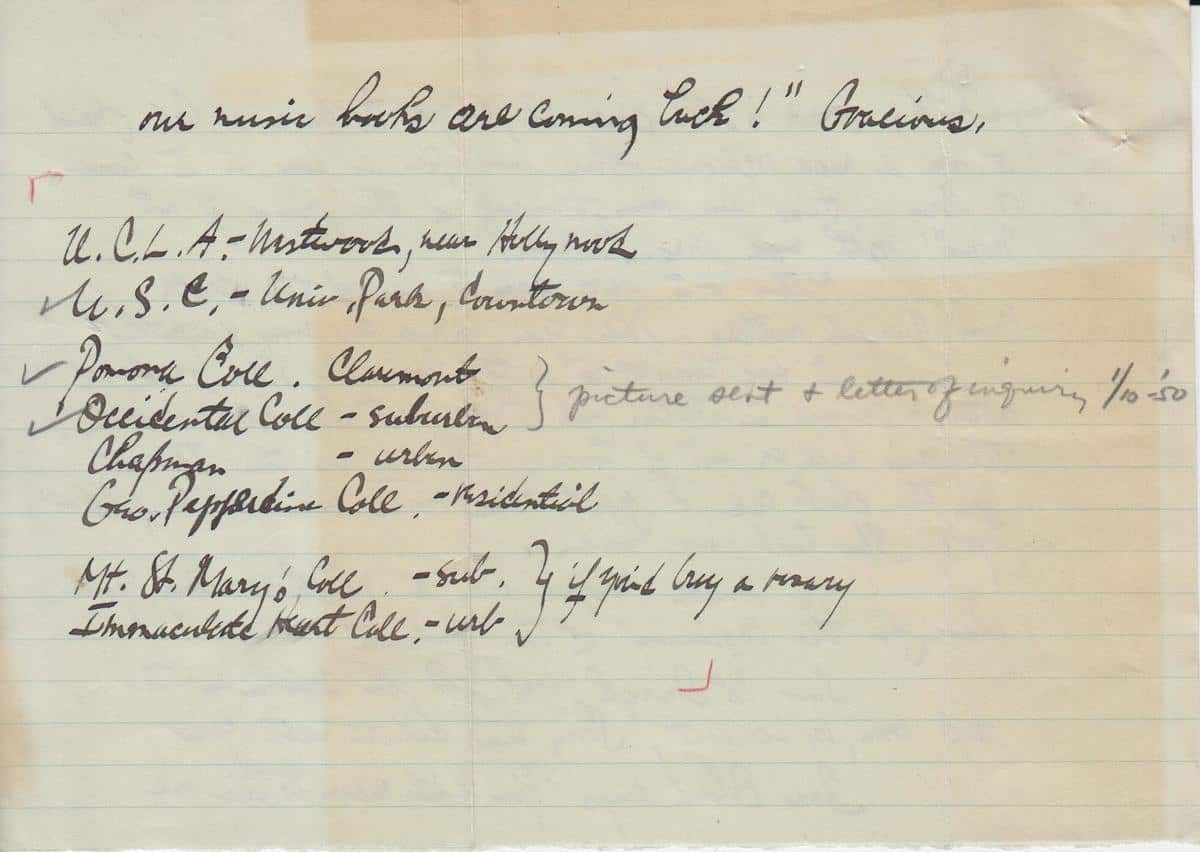

Meet Dorothy Wirtz

A few years after the Iowa Women’s Archives opened, Dr. Dorothy Wirtz [1915 – 2013] donated some pieces of her college years at the University of Iowa. Dorothy Wirtz’s 1997 gift to the IWA includes her academic articles and a selection of her poetry. However, the papers mostly concern the exploits of Wirtz and herContinue reading “Meet Dorothy Wirtz”