This piece was composed by IWA graduate assistant Andrea Leusink.

In the spring of 1965, Marion Helland, a fifth-grade teacher in New Hope, Minnesota, was flipping through the latest issue of the American Federation of Teachers newsletter when an ad calling for Freedom School teachers caught her eye.

Helland, whose teaching career had begun in Iowa almost 20 years prior, was ready to seek out new challenges. She was also an advocate for racial equality who, in the weeks since the Selma-Montgomery marches, had been searching for a way to contribute more to the movement. Maybe these “Freedom Schools” the ad described—temporary, free, all-ages schools set up by civil rights activists in the South, which taught civics, Black history, and organizing tactics in addition to reading, writing, and arithmetic—were the opportunity she’d been waiting for. She knew it would be dangerous—three civil rights workers had been murdered the previous summer in Mississippi, and Helland’s parents begged her not to go—but she was determined to honor her conviction that “every person who possibly can do so, should help in a direct way.”1

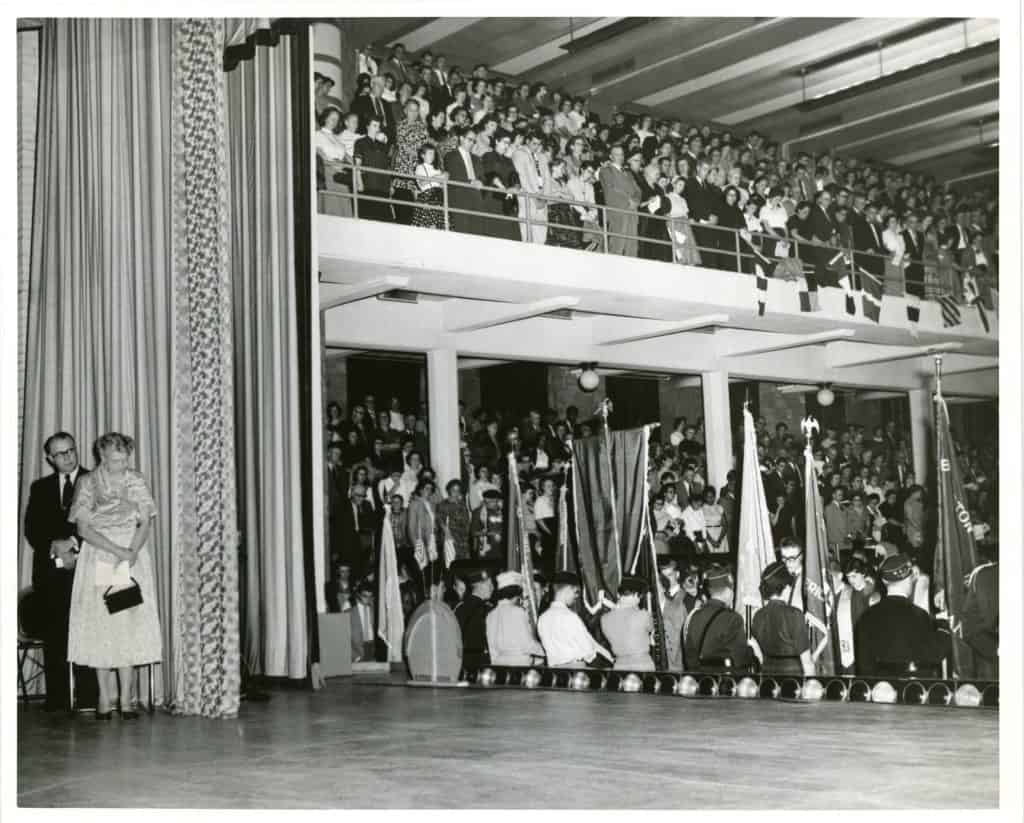

That summer Helland received the news that she was to be sent to Gadsden, Alabama, the site of the notorious 1906 lynching of Buck Richardson, to help set up a Freedom School there. In preparation, she attended training sessions at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Atlanta, Georgia, where she received instruction in self-defense, voter canvassing, and class preparation. The sessions promoted a non-violent philosophy but nonetheless acknowledged the possibility of targeted violence against the volunteers; those like Helland who would be staying in a “Freedom House” (as the homes of the movement’s local hosts were known) were told to draw the shades when indoors and, if approached by police, decline to provide any information about who they were staying with.

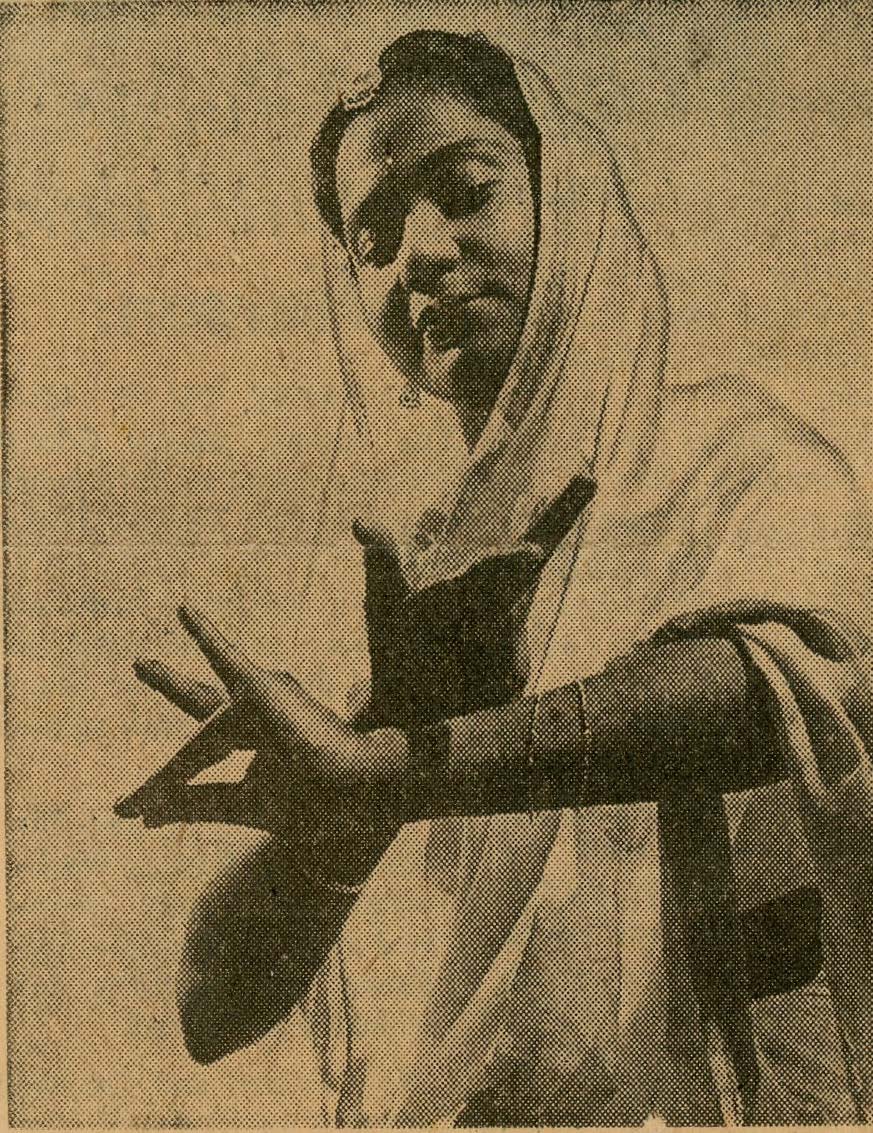

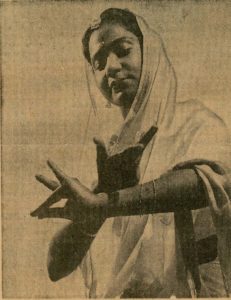

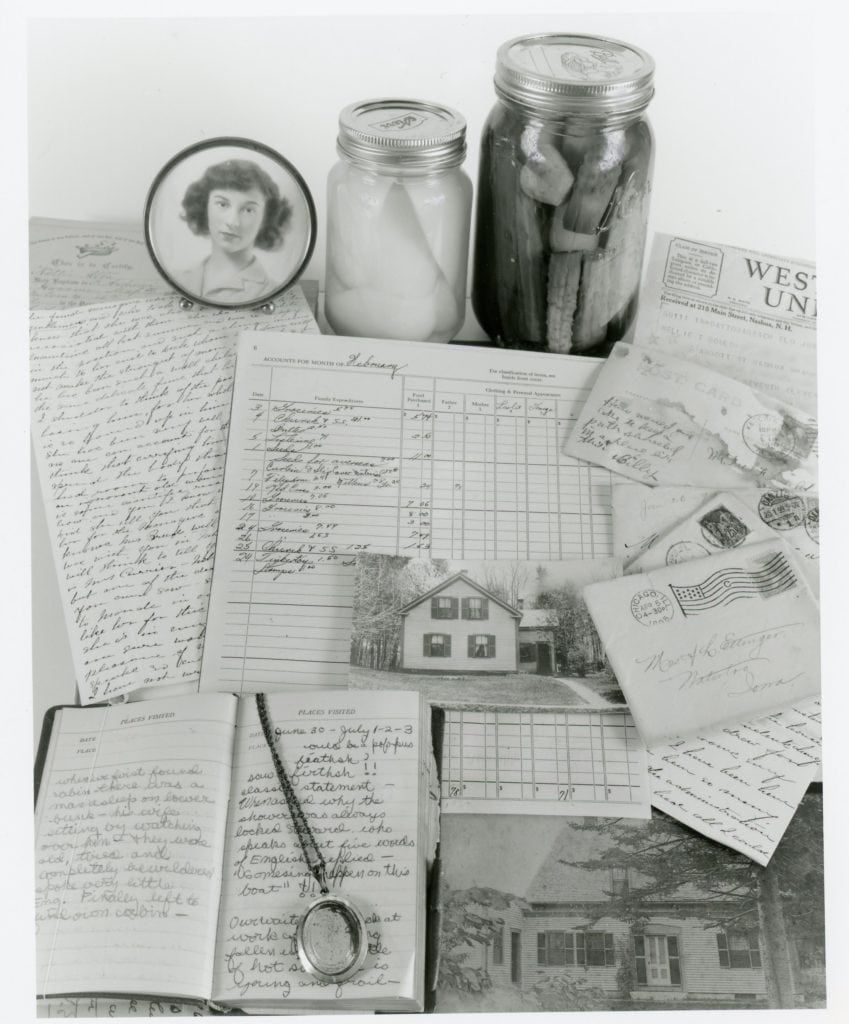

A natural self-archivist who could sense the historical importance of the events around her, Helland worked to document what she saw in and around the Freedom Schools. She photographed her students, local organizers, and fellow out-of-town volunteers, as well as evidence of social segregation, such as signs reading “Colored Only.” She also visited local schools and recorded ways they were unequal to white facilities, collected segregated job ads from Southern newspapers, and sought out opportunities to gather information about what life was like in the Jim Crow South.

One such opportunity came on Helland’s very first day in Gadsden, when she saw another ad that made a big impression on her: this time, a newspaper announcement for a local Klan meeting to be held that night with “prized speaker” Collie Leroy Wilkins. Wilkins was one of four Klansmen who had shot and killed activist Viola Gregg Liuzzo that spring (around the same time that Helland had seen the Freedom School ad). This meeting presented her with an opportunity that she could not pass up. With the other Freedom School teachers, Helland snuck in and listened closely, later taking notes about the meeting in her journal.2 She was shocked to find that the gathering “had records of Christian hymns playing as we marched in,” as well as “young children in Klan outfits.”3 Helland later suspected Klan involvement when she and another Freedom School teacher began taking Black students on field trips, only to repeatedly find themselves getting mysterious flat tires.4

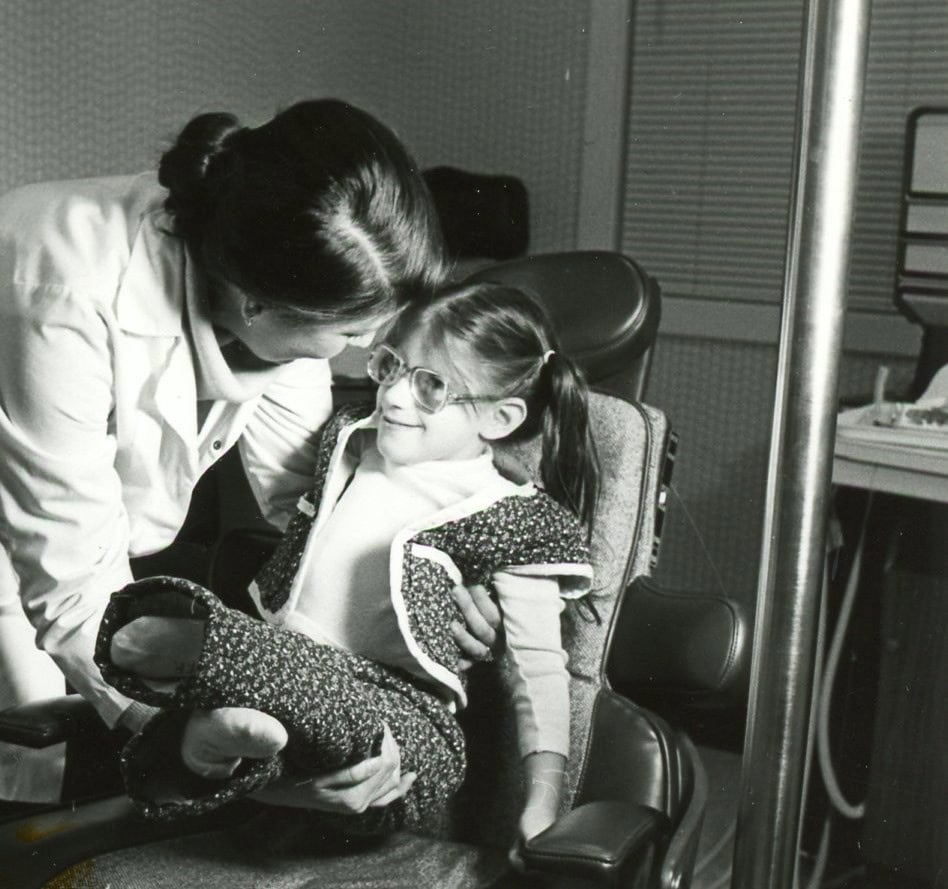

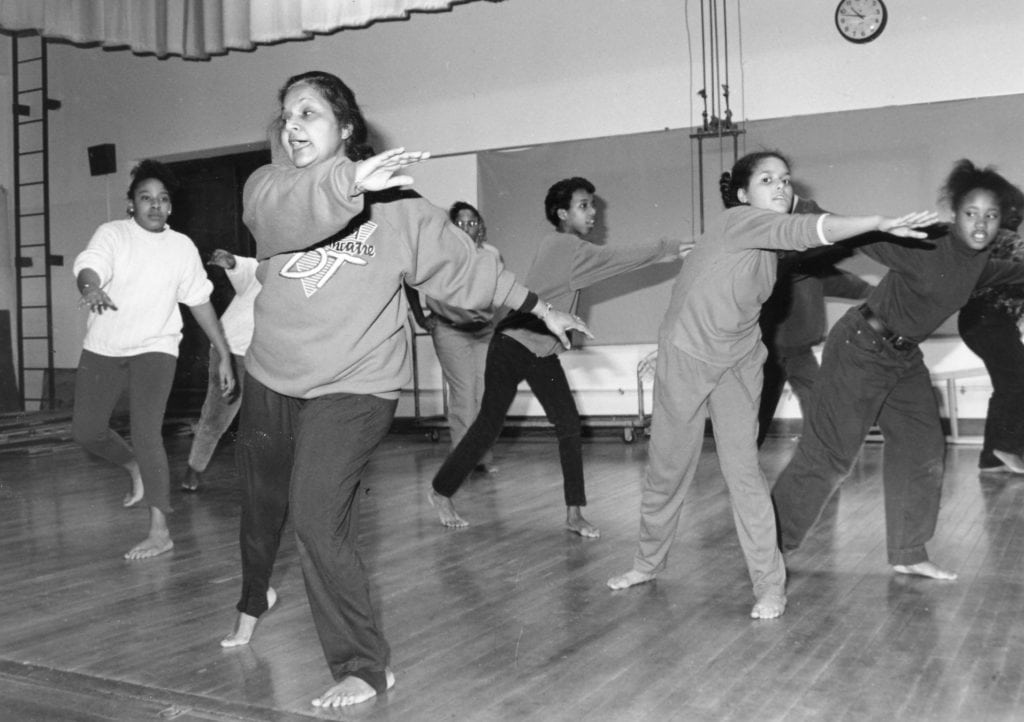

Still, whatever fear Helland experienced was not enough to keep her from returning as a Freedom School teacher in the summer of 1966; this time, she was sent to Columbia, Mississippi, where she taught reading, writing, art, and Black history. The Robbinsdale school district, where Helland taught during the school year, had fundraised to buy a car that she would drive down to Mississippi and, at the conclusion of her tenure, leave there for use by local movement activists.

One night that summer, a group of Klan members arrived at the Freedom House where Helland and fellow volunteer Lynn Porteous were staying and attempted to burn a kerosene-soaked cross on the front lawn. Porteous managed to scare them off by shooting a shotgun over the Klansmens’ heads. Following this incident, a two-way radio system was installed in Helland’s car to allow her to call for help if she was being followed. Both Porteous and Helland continued their work in Columbia after this incident, though they moved from the targeted house to lodgings on a farm for the remainder of the summer.

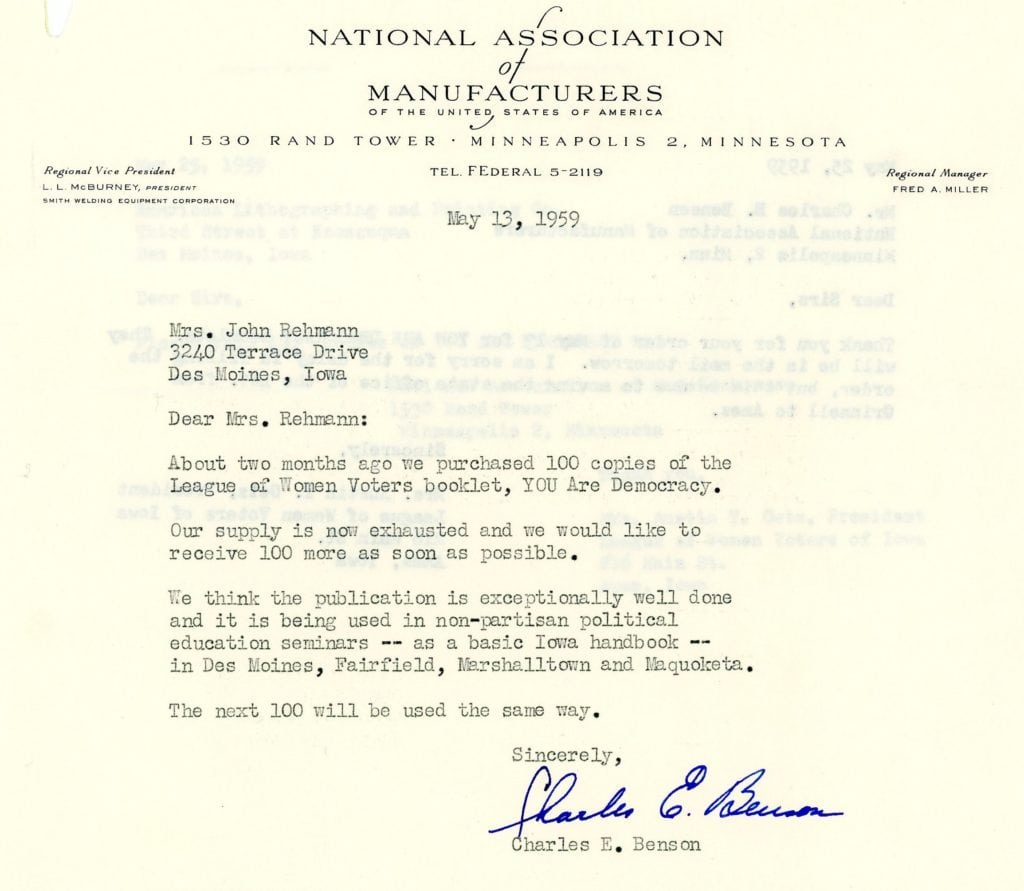

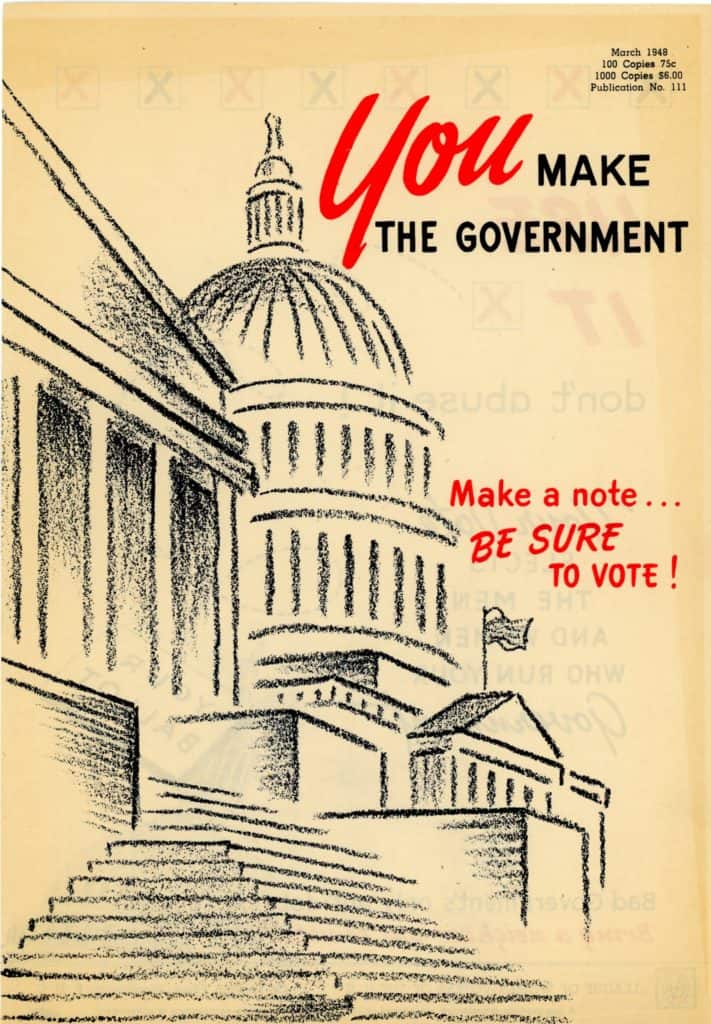

In addition to her Freedom School teaching, Helland also volunteered with voter registration drives, canvassing door to door and assisting with citizenship and political education for adults. Along with 15 other volunteers, she registered almost 1,000 new Alabama voters in July 1965; by early 1966, the SCLC estimated that these efforts had resulted in more than 175,000 new voters in Southern states.5

While 1966 proved to be her final summer as a Freedom School teacher, it was not the end of Helland’s anti-racist activism. In 1968, she traveled to Washington, D.C. as part of the Minnesota delegation to Resurrection City, an encampment of 3,000 people organized by the Poor People’s Campaign to protest the failure of President Lyndon Johnson’s war on poverty. The shantytown was intended to “display reality so that others may understand and attempt to correct the problem,” as Helland wrote. The City consisted of “15 acres—600 huts” and saw “eight inches of rain in six weeks [that] didn’t let up [for] three days and two nights.”6 Helland recalled that the visibility of the protestors (“a scar on the picture-postcard beauty of Washington D.C.”) was a way of symbolically pushing back against the status-quo belief that “poor are ok as long as they stay in their place and remain invisible.”7

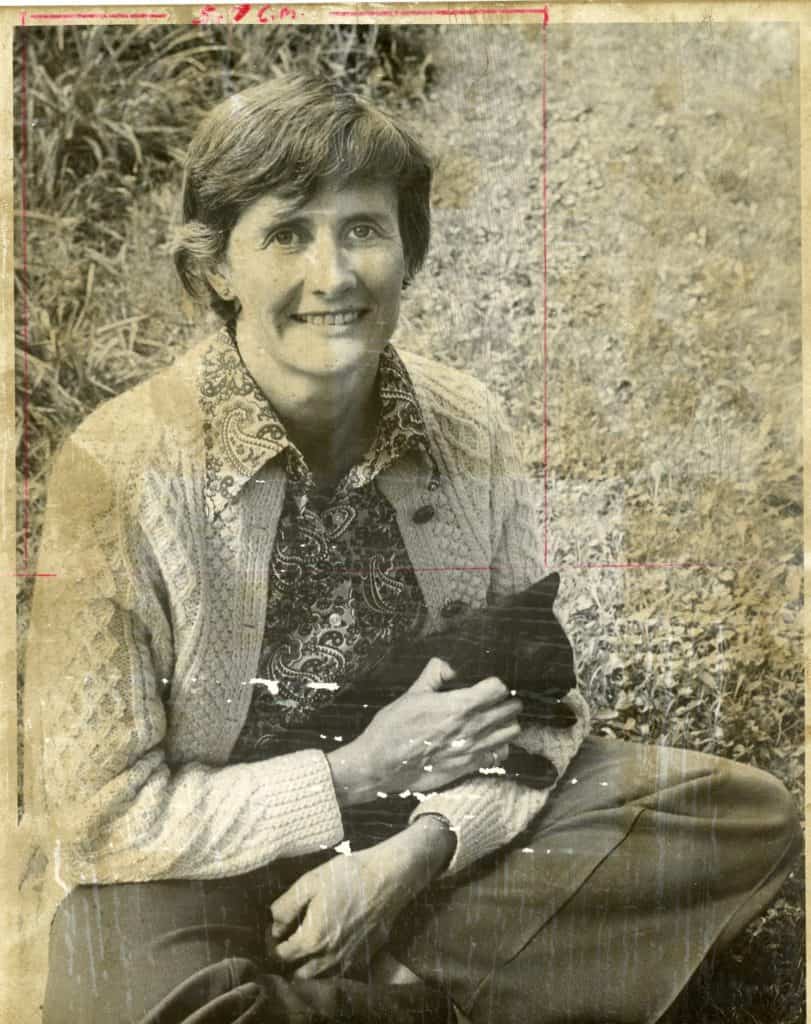

Helland often credited her experiences during her Freedom School summers and her time in Resurrection City as formative; they taught her to look at the world differently, and this in turn led her to teach differently than she had before. Helland was passionate about improving the way Minnesota schools taught the histories of Black and Native American people, groups that have long been underrepresented in the historical record. She drew on the photos and other materials she collected during her Freedom Summers to create educational packets about the Civil Rights Movement that she shared widely with others and presented to community groups. In the 1980s, Helland participated in a number of major curriculum development initiatives in the state. She also practiced new techniques with her students, such as helping them annotate and respond to examples of bias that they found in U.S. history textbooks or consumer products.

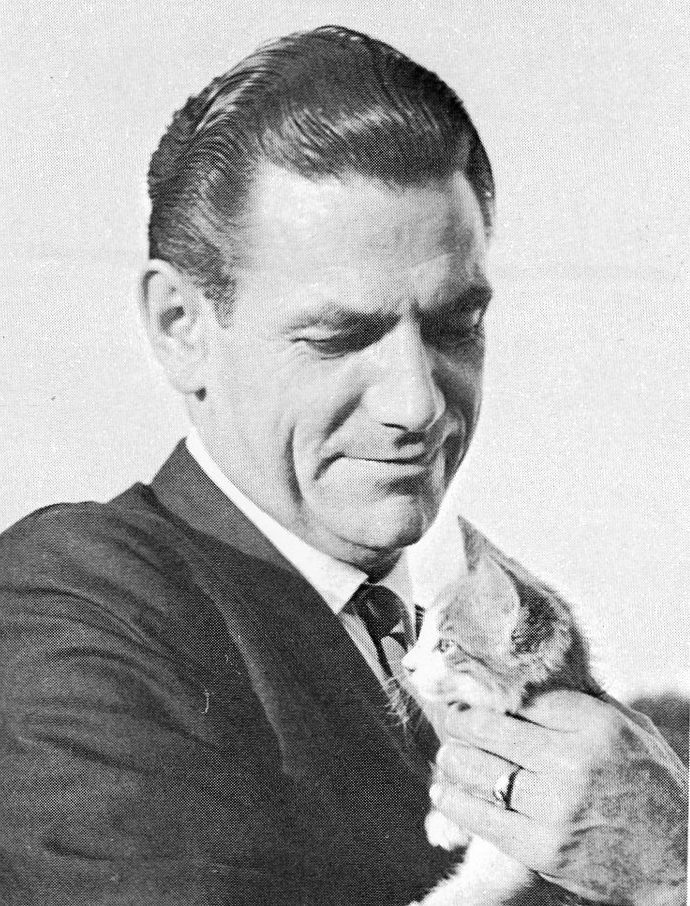

Helland retired from teaching in 1992 after 39 years, though she continued to volunteer with civil rights and anti-hate organizations in Minnesota, winning several awards for this activism. In 2017, Helland moved with her husband, David Lee Crawford, to Spencer, Iowa, where both passed away in 2018.

Helland’s story can be looked at through several lenses. For some scholars, her biography could serve as a concrete example of how the grassroots direct action of the 1950s–1960s Civil Rights Movement evolved into the bureaucratic reforms of subsequent decades. From a genealogical perspective, Helland’s story is one of many that illustrates how Nordic immigration shaped the upper Midwest and its culture. And from an archival point of view, her papers demonstrate the power that local and family histories have to move people and bring them together.

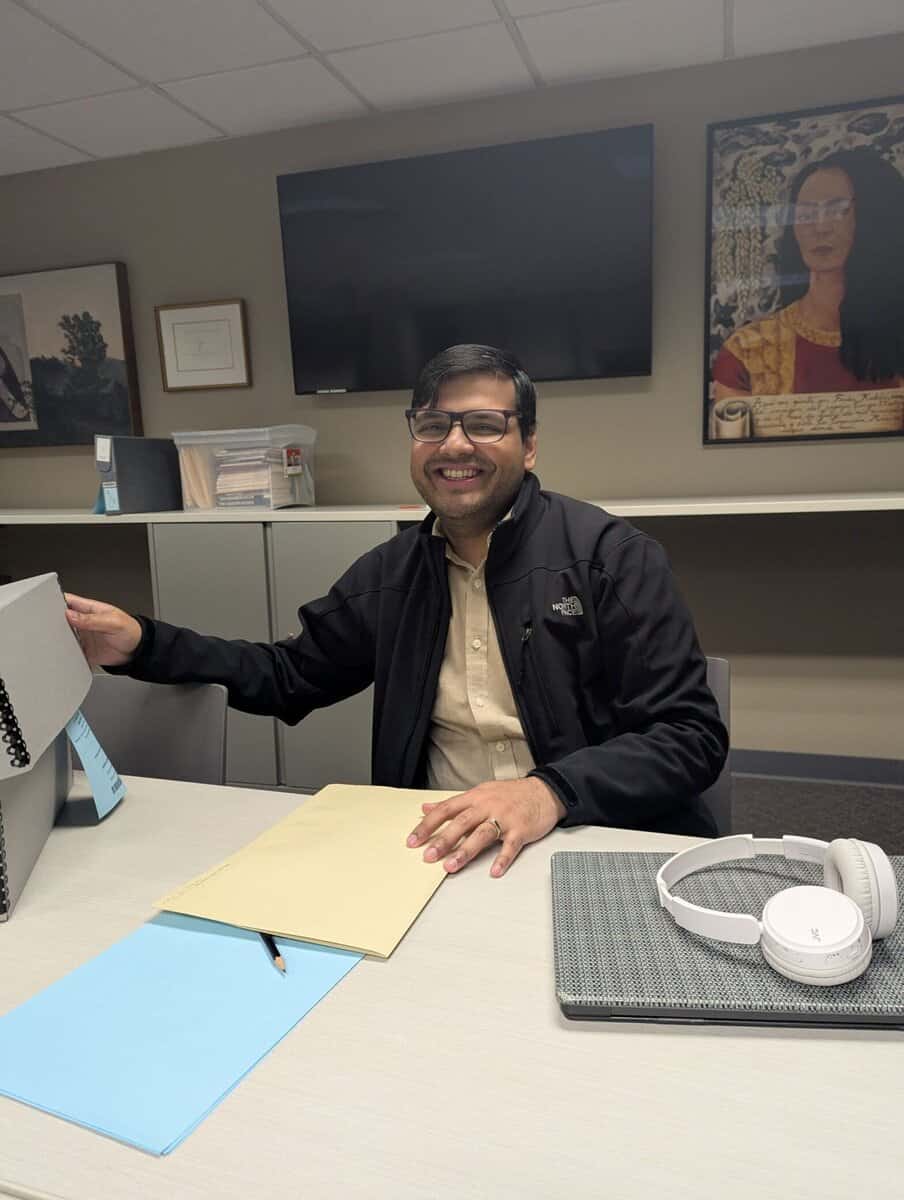

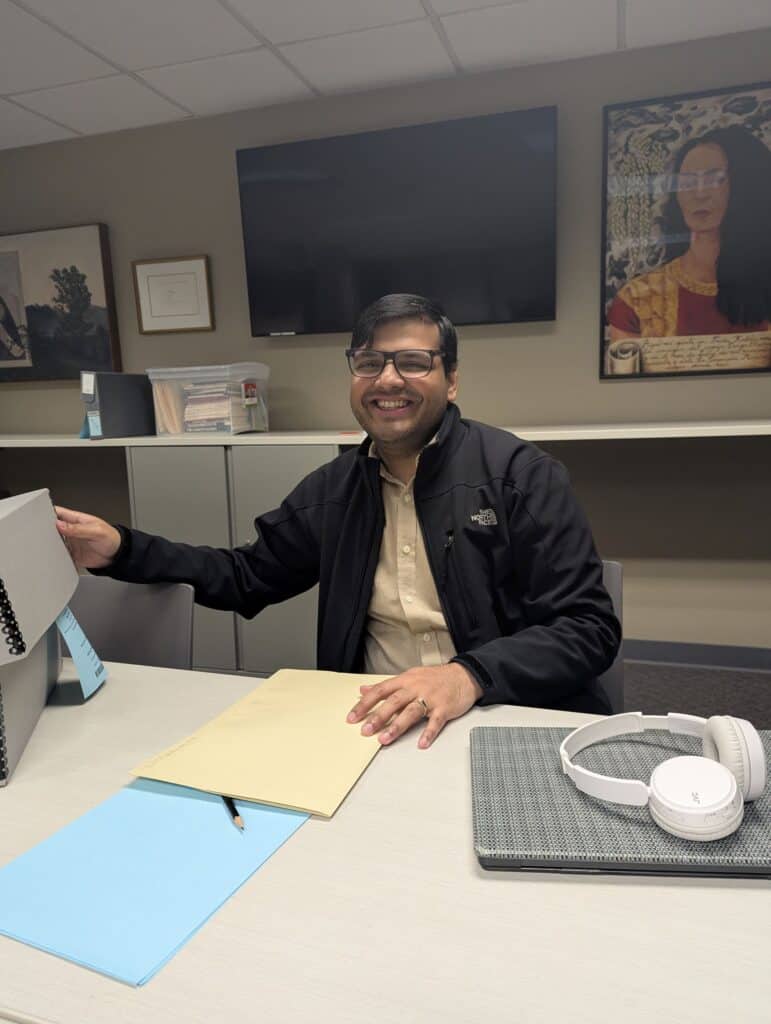

Now, Helland’s nieces, Diana Koppen and Pam Doocy-Curry (both teachers themselves), are working to preserve her legacy and share her story. The Helland papers in the Iowa Women’s Archives at the University of Iowa Libraries include a copy of their biography of Helland, as well as record reflecting their public speaking engagements (like this one at the Spencer Public Library in 2022) and an exhibit about Helland’s life that they curated at the Clay County Heritage Center in 2023. Koppen and Doocy-Curry have also provided invaluable assistance to IWA staff in our work to transfer, arrange, and describe these materials.

Recently, IWA featured Helland’s photographs from Resurrection City in an archival session with students from the UI N.E.W. Leadership program, which seeks to empower women and other students who may not traditionally serve in public office with training in civic engagement, advocacy, and the political process. It’s a testament to Helland’s identity as a consummate teacher that even the traces she left behind—her photos and letters, her scrapbooks and journals—are still teaching, inspiring students who, like Helland, feel called to serve others and make a difference in our world.

To view material from the Marion Helland papers, stop by IWA during our open hours or email us at lib-women@uiowa.edu.

- Marion Helland journal, 1965, IWA1390, Box 5, Freedom school journals 1965-68 folder, Marion Helland papers, Iowa Women’s Archives, Iowa City, Iowa. ↩︎

- 2 Handwritten Gadsden journal, Helland papers, Box 5, Freedom school journals folder. ↩︎

- Koppen, Diana and Pam Doocy-Curry, Breaking Free from Rigid Boxes: From the Outside Looking In: Marion Helland, Nine Decades of Civil Rights Service (Monee, IL: privately printed, 2021), 36. ↩︎

- 4 Letter from Helland to Minnesota students, September 3, 1965, Helland papers, Box 6, What more can I do? binder, folder 1 of 4. ↩︎

- The total for the Gadsden regional registration efforts can be found in the Helland papers, Box 5, Activism: Freedom school journals folder; the SCLC statistic can be found in Box 5, Activism: Correspondence folder. ↩︎

- 1968 Poor People’s Campaign journal, Helland papers, Box 5, Freedom school journals folder. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎