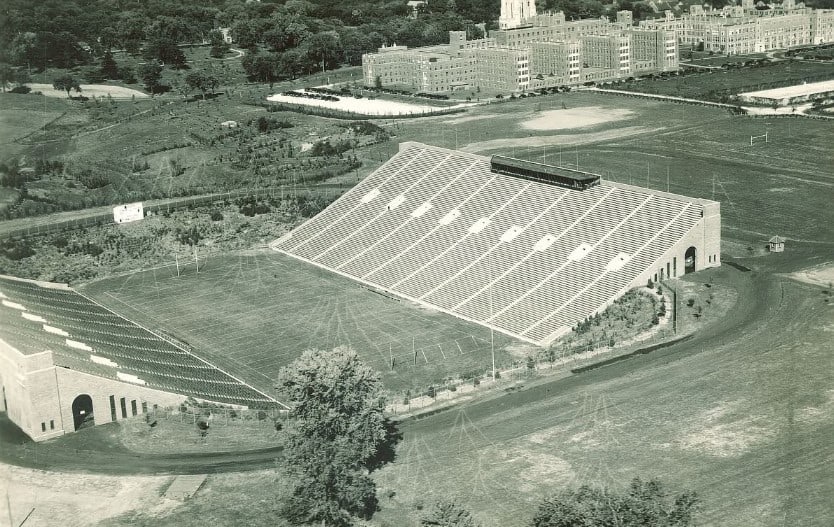

This series features the work and research of UI students. The following is written by Calvin Covington, Olson graduate research assistant. I’d wager that, even if they haven’t gone to a game, most of Iowa City’s population has borne witness to the grand Kinnick Stadium, where, every football season, legions of fans flock to watchContinue reading “Students investigate: the surprisingly long story of how Kinnick Stadium got its name”

Tag Archives: student work

A king by any other name would die as duly, or the top 10 nicknames of Louis XVI

The following is written by Libraries student employee Brianna Bowers. The few short months from the fall of 1792 to January 1793, in which heated debate and a final vote decided that Louis XVI would be guillotined, held centuries of progress. Our world would not be recognizable without the French Revolution. The University of IowaContinue reading “A king by any other name would die as duly, or the top 10 nicknames of Louis XVI”

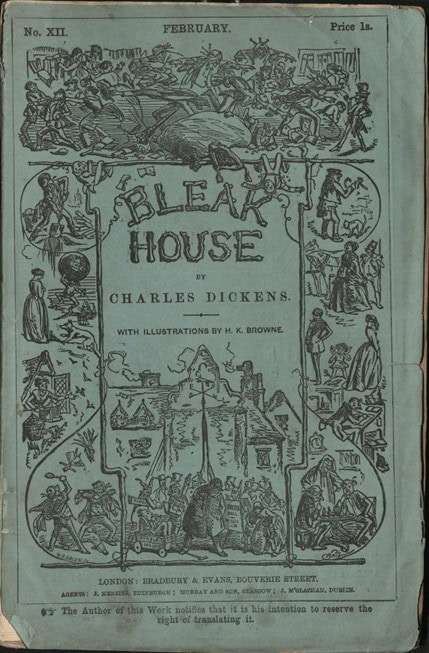

Stepping into the bustling world of Bleak House’s first readers

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit Special Collections and Archives at the University of Iowa Libraries. Below is a blog by Casie Minot from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “Reading Culture History & Research in Media” (SLIS:5600:0EXW). Minot explores the paratext ofContinue reading “Stepping into the bustling world of Bleak House’s first readers”

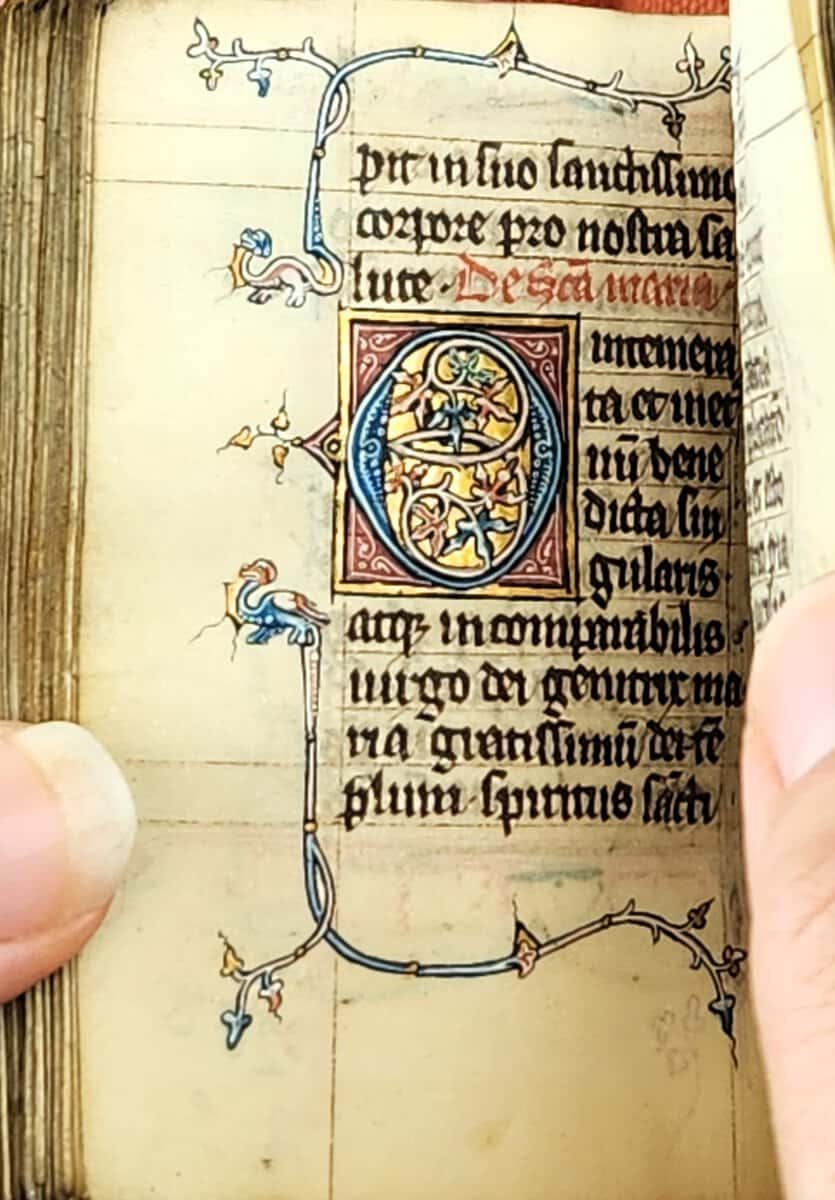

Beware of marginal monsters

The following is written by Museum Studies Intern Joy Curry. This 14th-century book of hours may be tiny, but it is jam-packed with beasts, ranging from fish to lions to feathered dragons. It’s a marvel that so much of the art has survived, especially since the book is missing 19 miniatures. Fortunately for us, theContinue reading “Beware of marginal monsters”

Language of flowers speaks volumes

The following is written by museum intern student Joy Curry. Valentine’s Day is, among other things, a common time to give and receive flowers. If you visited a florist this last holiday, you might have seen some explanations on what flowers mean. You may have heard of the symbolism attached to different colors of rosesContinue reading “Language of flowers speaks volumes”

The Legacy of Flatland

The following was written by Marie Ernster, practicum student from School of Library and Information Science The field of mathematics was in a period of philosophical volatility in England in the 19th century. A huge debate raged in the area of geometry over whether they should allow non-Euclidean concepts to enter the pedagogy. Among theContinue reading “The Legacy of Flatland”

The Sam Hamod Saga, Part One: Making Introductions

The following is written by graduate student Bailey Adolph, who is processing the Sam Hamod Papers. “Thus, we gain richness from our heritage—but we should not be limited as writers by our ethnicity.” — Sam Hamod, “Ethos and Ethnos: The Ethnic Writer in the USA” At the beginning of the summer, the University of IowaContinue reading “The Sam Hamod Saga, Part One: Making Introductions”

An Artist’s Perspective: Travel Diary of Stuart Travis

The following is written by our Workplace Learning Connection summer intern Cassady Jackson Stuart Travis (1868-1942) was an American artist who was accepted into art school in France during the latter half of the 19th century. He was just nineteen years old when he made the journey alone from New York to Europe. In hisContinue reading “An Artist’s Perspective: Travel Diary of Stuart Travis”