The following is written by Asian Alumni and Student Oral History Project Intern Jin Chang Since the start of the pandemic, prominent leaders have stood in front of crowds of American people calling COVID-19 the “China Virus” and “Kung Flu.” As a result, Chinatown businesses closed as tourists continued to avoid Chinatowns across America and raciallyContinue reading “University of Iowa Asian American Oral History Archive”

Tag Archives: Anti-Asian Racism

Anti-Asian Racism Historically Archived

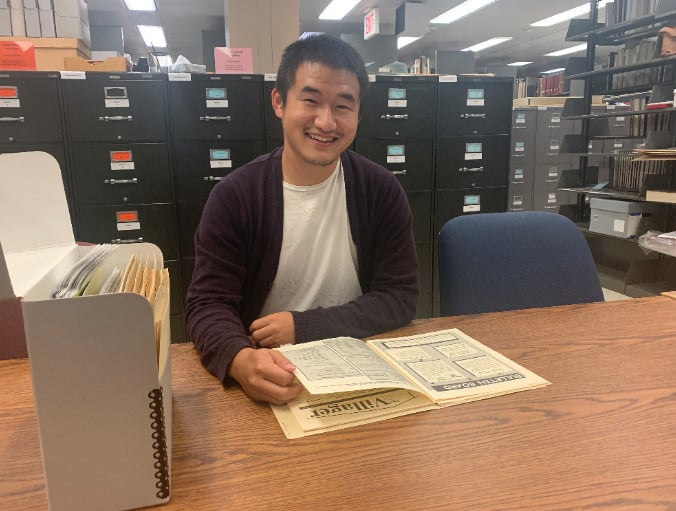

“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Robert Henderson from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0001). A note from the University Libraries: Some resources in our collections may contain offensive stereotypes,Continue reading “Anti-Asian Racism Historically Archived”