The following post was written by IWA Graduate Assistant, Emma Barton-Norris. Six-on-six girls’ basketball was extremely important in Iowa, to both those who played the game and to those who made the trek to attend the annual Iowa State Championship every year. In the newly processed collection, Six-on-Six Girls Basketball in Iowa ephemera, the storiesContinue reading “Six-on-Six Basketball: Gone but Not Forgotten”

Author Archives: Anna Holland

Community Collaboration brings Latinx History from the Archives to the Classroom

This fall, Yamila Transtenvot, an instructor in Spanish at Cornell College, has been working with IWA, The League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) Council 10, and the Davenport Community School District (DCSD) to bring primary sources about Latino/a/x history to Iowa schools. I sat down with Transtenvot this Latinx Heritage Month to discuss thisContinue reading “Community Collaboration brings Latinx History from the Archives to the Classroom”

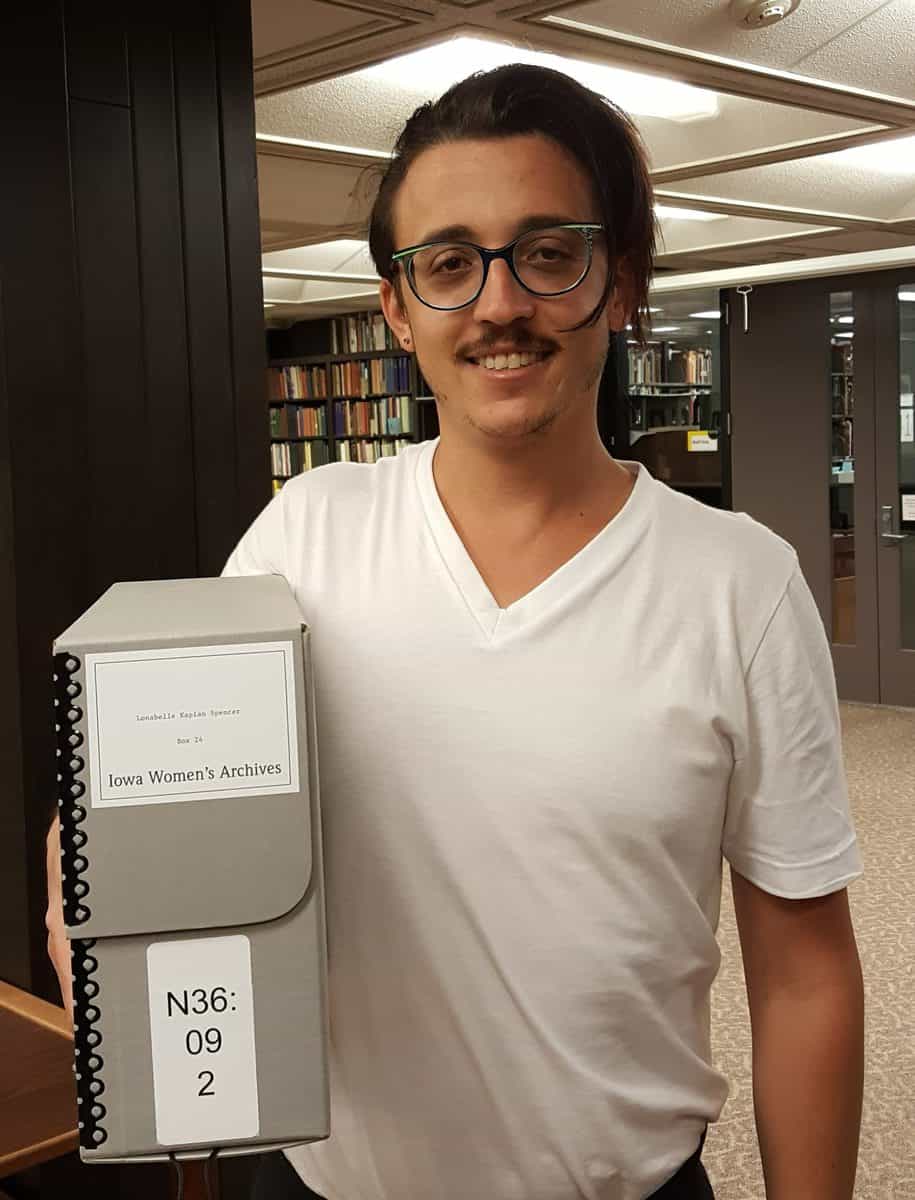

IWA’s 2021 Kerber Grant Recipient Finds Personal Stories within Industrial Agriculture

In Box 24 of the Lonabelle Kaplan Spencer papers, Andrew Seber finally found exactly what he was looking for: personal testimonies by rural citizens whose lives were turned upside down by the development of hog confinements near their Iowa homes. Seber’s dissertation, Neither Factory nor Farm: the Other Environmental Movement, will focus on industrial animalContinue reading “IWA’s 2021 Kerber Grant Recipient Finds Personal Stories within Industrial Agriculture”

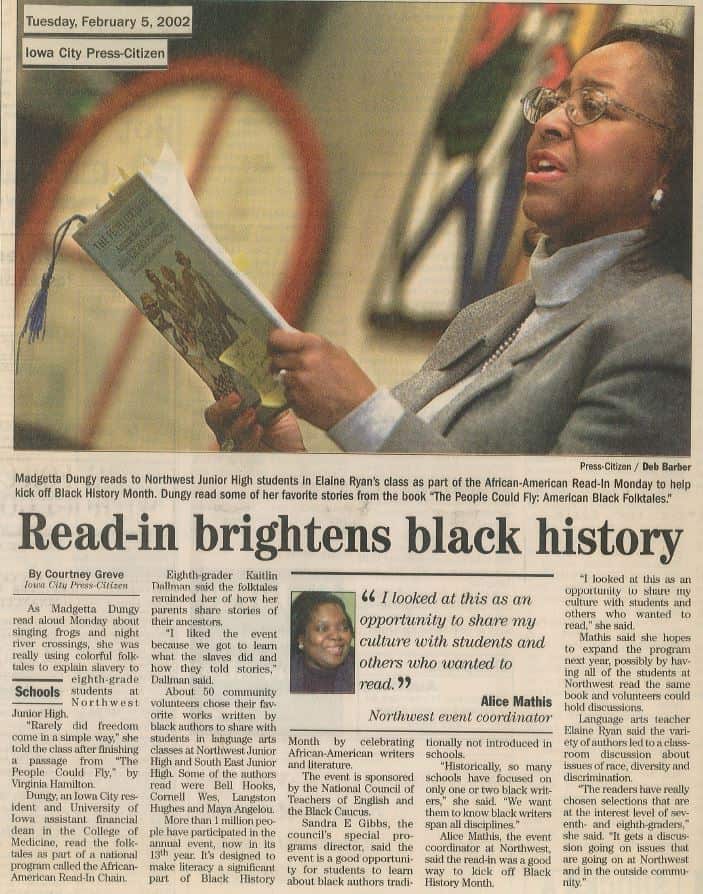

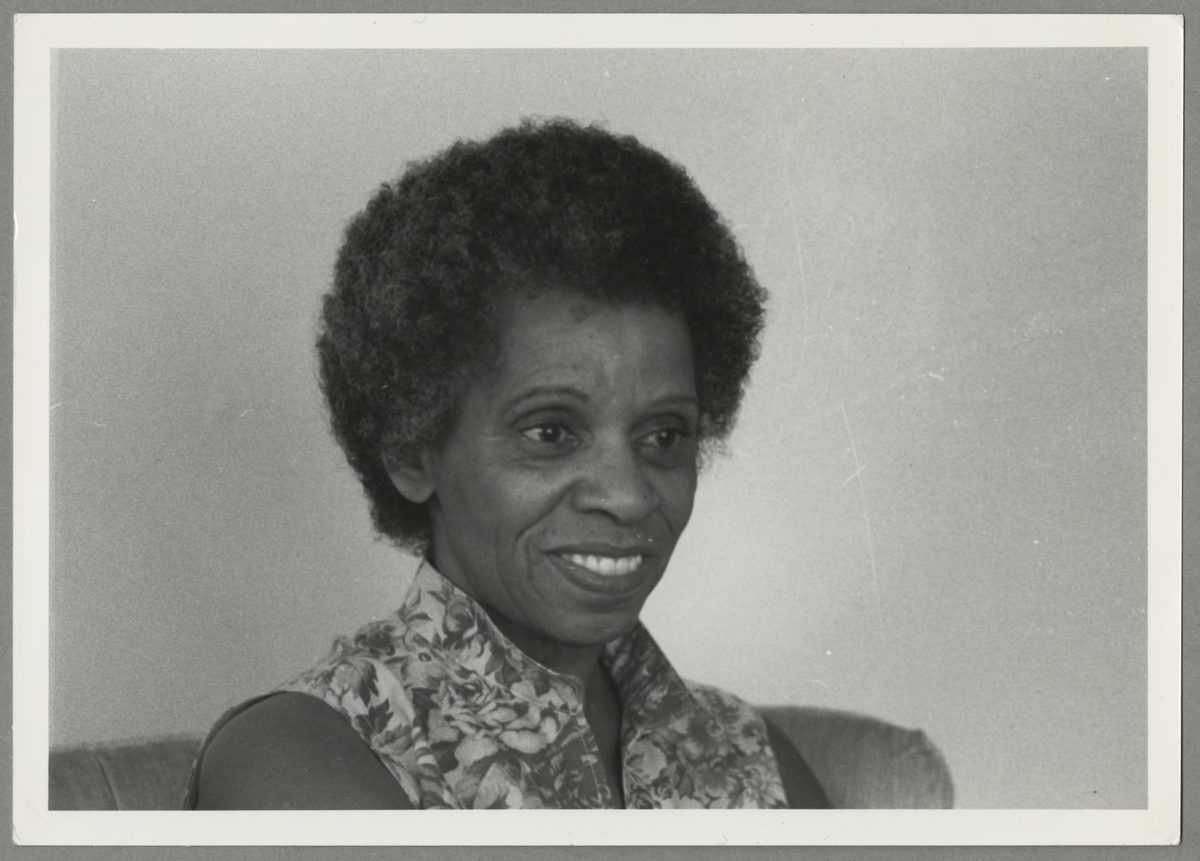

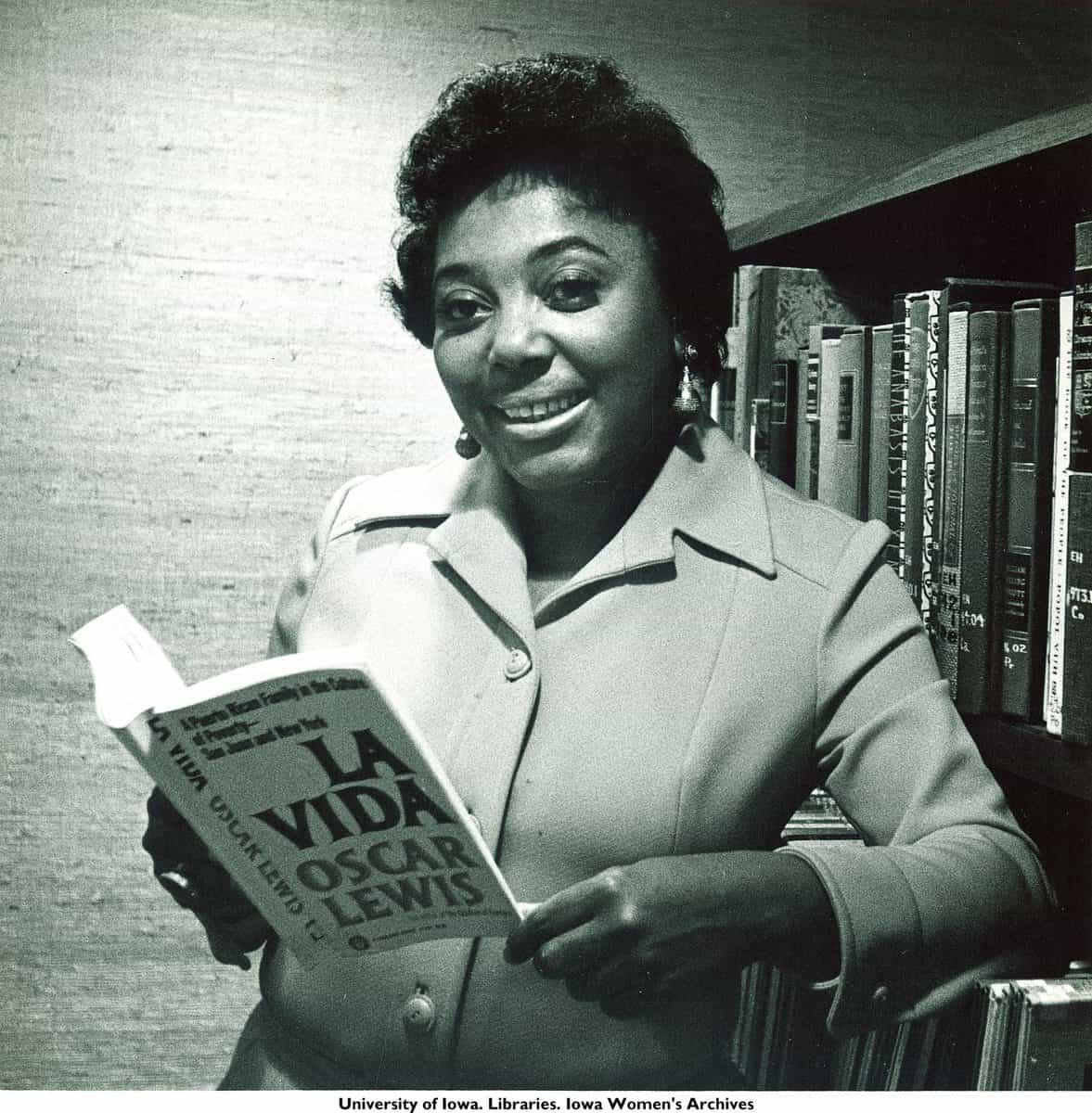

Student Reflection: Processing the Madgetta Dungy Papers

The following post is written by University of Iowa senior, Jack Kamp. When I started my internship at the Iowa Women’s Archives (IWA), I knew I was interested in working with Black women’s history. As a student interested in the history of civil rights and social justice, I knew that this collection would giveContinue reading “Student Reflection: Processing the Madgetta Dungy Papers”

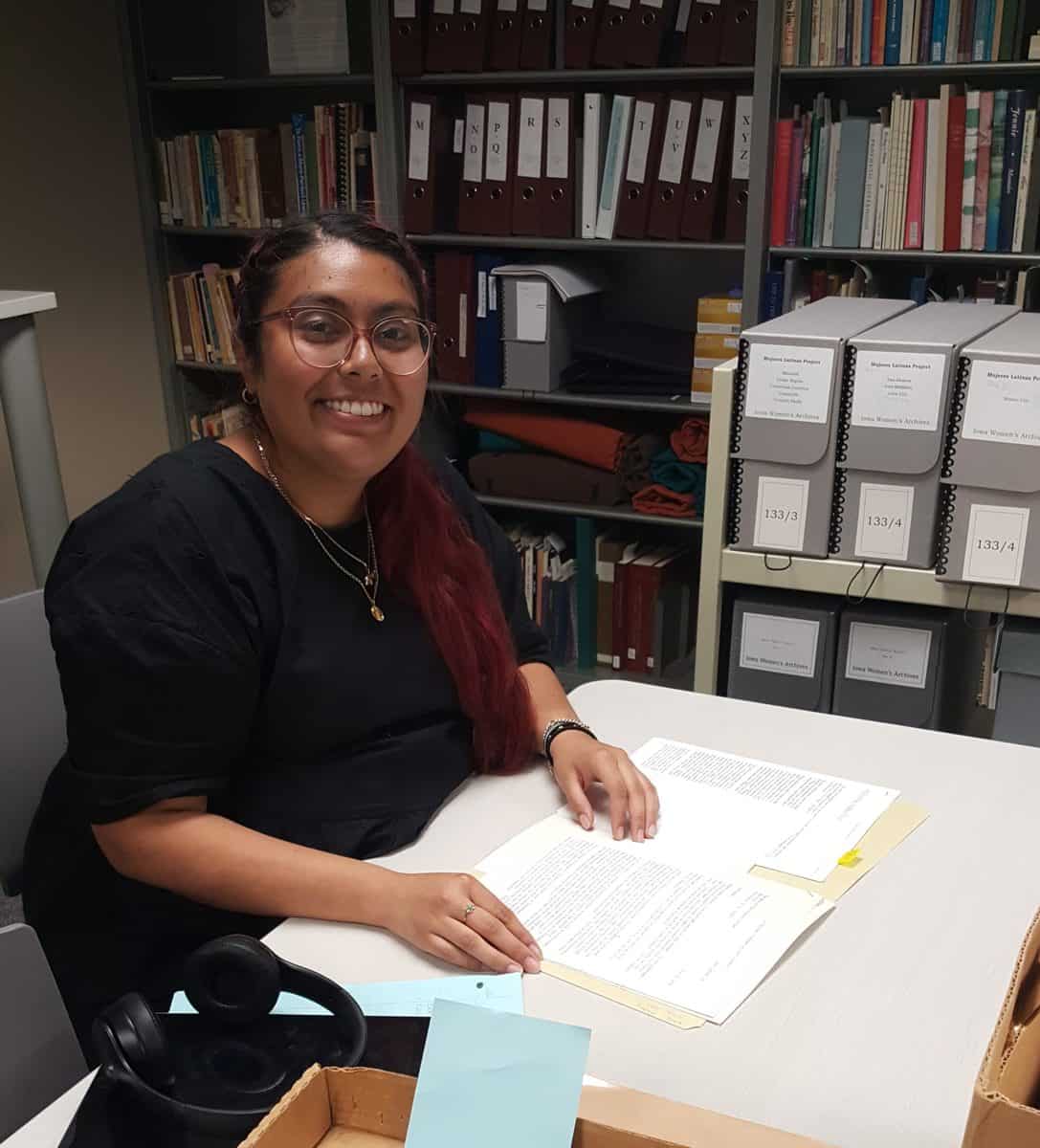

IWA’s 2020 Kerber Grant Recipient: Yazmin Gomez

After the pandemic postponed her research trip, Yazmin Gomez, the 2020 Linda and Richard Kerber Travel Grant recipient, finally made it to IWA! Linda Kerber, May Brodbeck Professor in the Liberal Arts and Professor of History Emerita, and her husband Richard founded this grant to help researchers, especially graduate students, travel to the Iowa Women’sContinue reading “IWA’s 2020 Kerber Grant Recipient: Yazmin Gomez”

Janice Beran and the Persistence of 6-on-6 Basketball in Iowa

This post was written by IWA Graduate Assistant, Erik Henderson In 1891, James Naismith invented the sport of basketball in Massachusetts at what is now Springfield College. In the early 1900s, the game was adopted for women throughout America especially in small town Iowa. The first Iowa State Championship for girls was played in 1920,Continue reading “Janice Beran and the Persistence of 6-on-6 Basketball in Iowa”

What Would You Attempt to Do If You Knew You Could Not Fail?

This post is by IWA Graduate Assistant Erik Henderson Taking a risk can be one of the most difficult things you must do. However, how would it feel knowing that you cannot fail no matter what you do? One thing that holds us back in life is our clouded judgment when making a major move.Continue reading “What Would You Attempt to Do If You Knew You Could Not Fail?”

Edna Griffin, Civil Rights Activist

This post is the tenth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. This past summer, we have seen a nationwide movement for change. In Iowa City, Philadelphia, Chicago, Seattle,Continue reading “Edna Griffin, Civil Rights Activist”

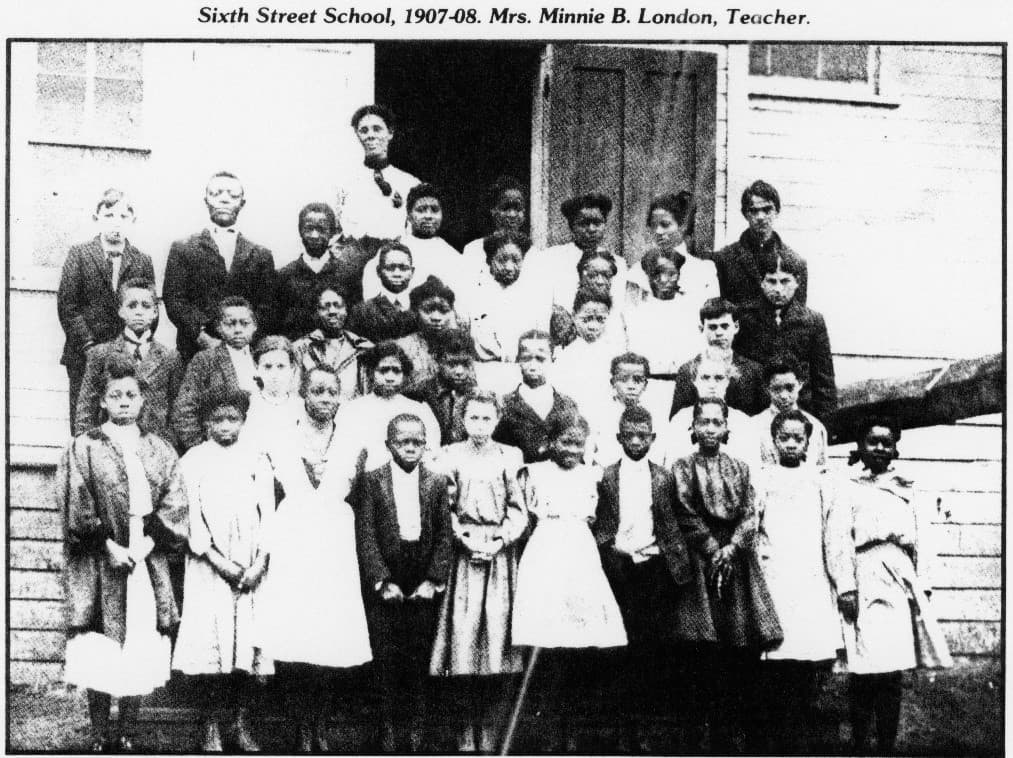

Reuben Gaines Memoir of Being Black in Buxton, Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Assistant, Erik Henderson, is the eighth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. The once prosperous coal mining town, Buxton, Iowa, approximately thirty minutes southwest of OskaloosaContinue reading “Reuben Gaines Memoir of Being Black in Buxton, Iowa”

Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader

This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the sixth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. Has anyone told you, you were going to be great in your youth?Continue reading “Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader”