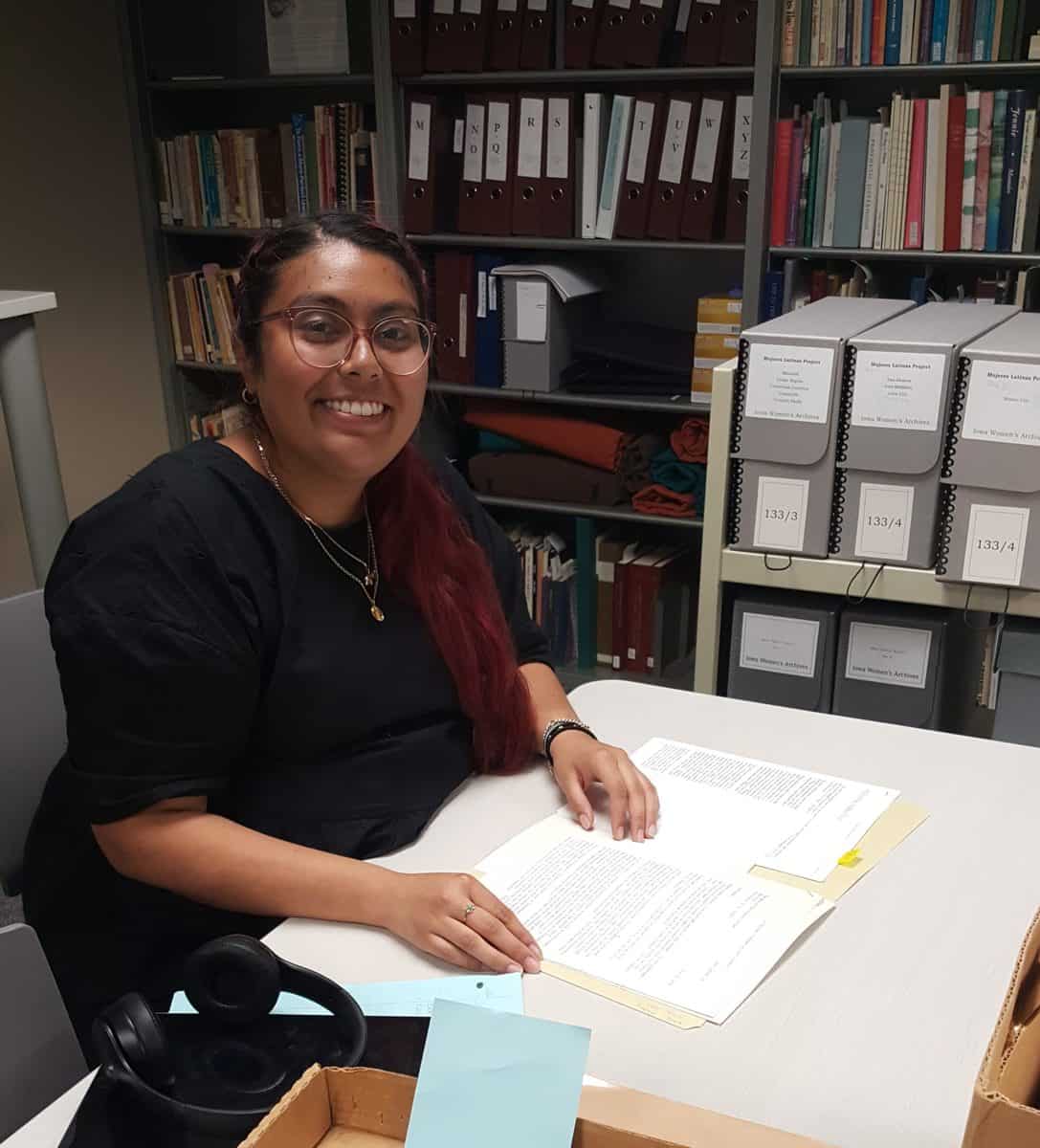

After the pandemic postponed her research trip, Yazmin Gomez, the 2020 Linda and Richard Kerber Travel Grant recipient, finally made it to IWA! Linda Kerber, May Brodbeck Professor in the Liberal Arts and Professor of History Emerita, and her husband Richard founded this grant to help researchers, especially graduate students, travel to the Iowa Women’sContinue reading “IWA’s 2020 Kerber Grant Recipient: Yazmin Gomez”

Tag Archives: lulac

From Alabama to the Barrio: Ernest Rodriguez and the Fight Against Racism in Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Research Assistant Heather Cooper is the ninth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the collections of the Iowa Women’s Archives. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. In honor of Latinx Heritage Month (September 15 – OctoberContinue reading “From Alabama to the Barrio: Ernest Rodriguez and the Fight Against Racism in Iowa”

Migration is Beautiful Website Premieres at 2016 National LULAC Convention

July 12th was the kickoff for the 2016 National LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens) convention. Janet, assistant curator here at the IWA, attended the conference to promote “Migration is Beautiful,” a new website featuring vignettes, oral history interview clips, memoirs, letters, and photographs from the IWA’s Mujeres Latinas Project. The new website highlightsContinue reading “Migration is Beautiful Website Premieres at 2016 National LULAC Convention”

Piñatas of Christmas Past

By Vitalina Nova, Preservation Projects Librarian Season’s greetings from the Iowa Women’s Archives! This is the time of treats and parties. Seen below are photographs of children in the 1960s – partaking of all the joys of holiday parties. These images come from the Iowa Women’s Archives LULAC (League of United Latino American Citizens) Council 10Continue reading “Piñatas of Christmas Past”

LULAC Christmas party, early 1960’s

Women’s History Wednesday: As part of its project to document the history of Iowa Latinas and their families, the Iowa Women’s Archives preserves and makes accessible the records of the LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens) Council 10 of Davenport, Iowa. Mexicans arrived in Iowa as early as the 1880s, and by theContinue reading “LULAC Christmas party, early 1960’s”

LULAC News, JFK Memorial Edition

This JFK Memorial Edition of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) National Newsletter is preserved in the records of LULAC Council 10 in the Iowa Women’s Archives. It commemorates President Kennedy and Mrs. Kennedy’s attendance at the LULAC banquet in Houston on November 21, 1963. Jacqueline Kennedy addressed the audience in Spanish on this first visit of anyContinue reading “LULAC News, JFK Memorial Edition”

About our exhibition “Pathways to Iowa”

In honor of the 20th anniversary of the Iowa Women’s Archives, we have mounted an exhibit in the North Exhibition Hall of the University of Iowa’s Main Library. The inspiration for this exhibit came from the many visits made to the archives by families and friends of donors. Earlier this year, Sam Becker broughtContinue reading “About our exhibition “Pathways to Iowa””