This post was written by IWA Graduate Assistant, Erik Henderson In 1891, James Naismith invented the sport of basketball in Massachusetts at what is now Springfield College. In the early 1900s, the game was adopted for women throughout America especially in small town Iowa. The first Iowa State Championship for girls was played in 1920,Continue reading “Janice Beran and the Persistence of 6-on-6 Basketball in Iowa”

Tag Archives: Erik Henderson

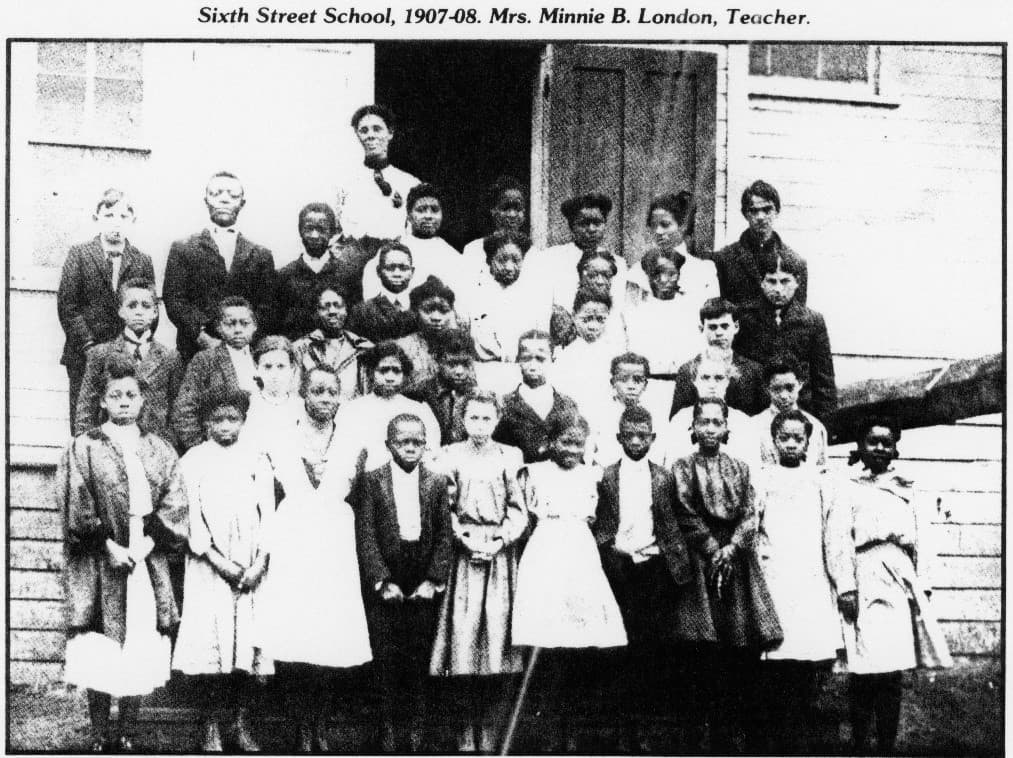

Reuben Gaines Memoir of Being Black in Buxton, Iowa

This post by IWA Graduate Assistant, Erik Henderson, is the eighth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. The once prosperous coal mining town, Buxton, Iowa, approximately thirty minutes southwest of OskaloosaContinue reading “Reuben Gaines Memoir of Being Black in Buxton, Iowa”

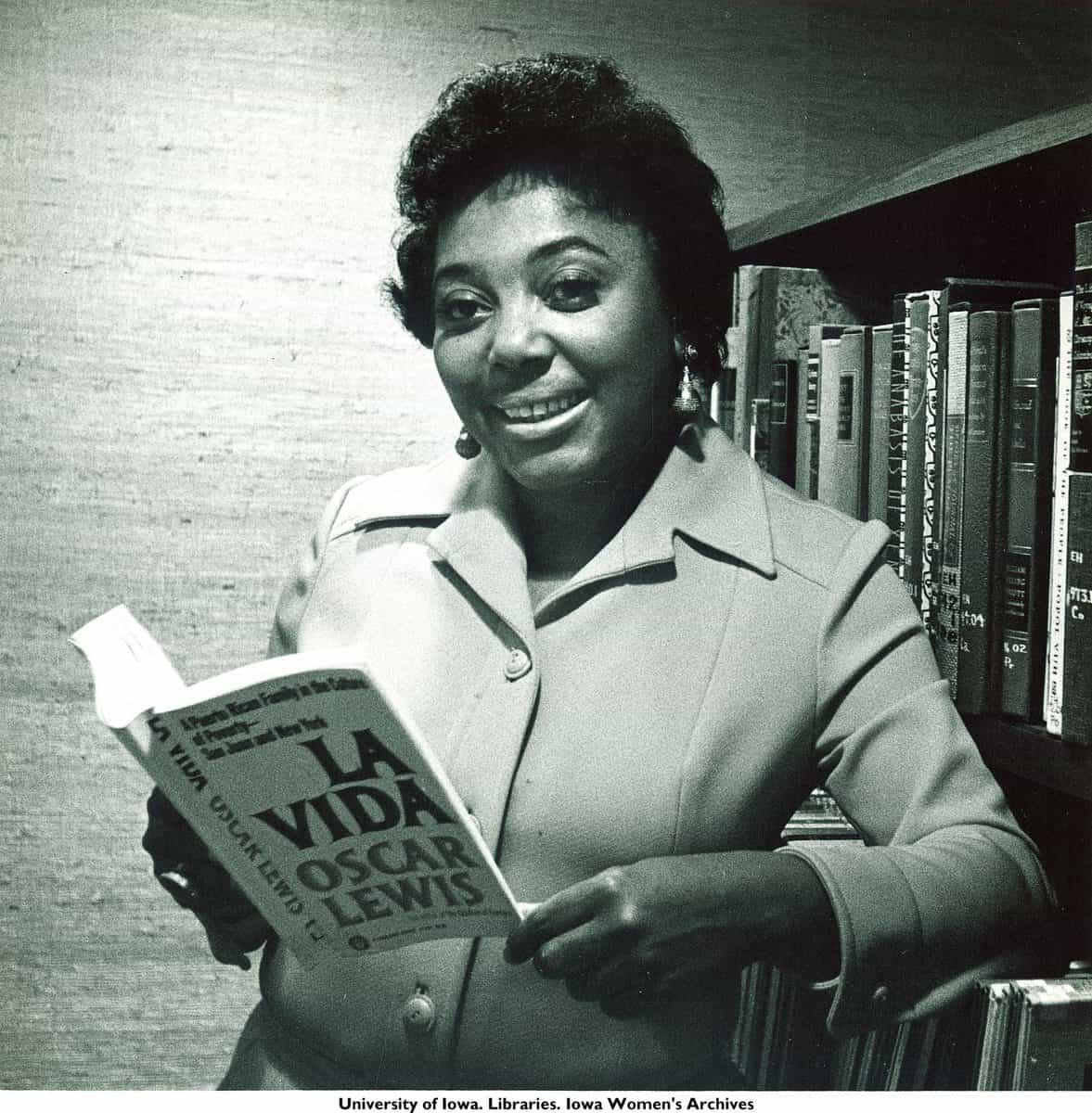

Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader

This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the sixth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. Has anyone told you, you were going to be great in your youth?Continue reading “Esther Walls: The Role of a Black Leader”

Martha Nash: An Iowa Advocate for Black Voices

This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the fourth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series has run weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020. The Martha Ann Furgerson Nash papers are filled with information about herContinue reading “Martha Nash: An Iowa Advocate for Black Voices”