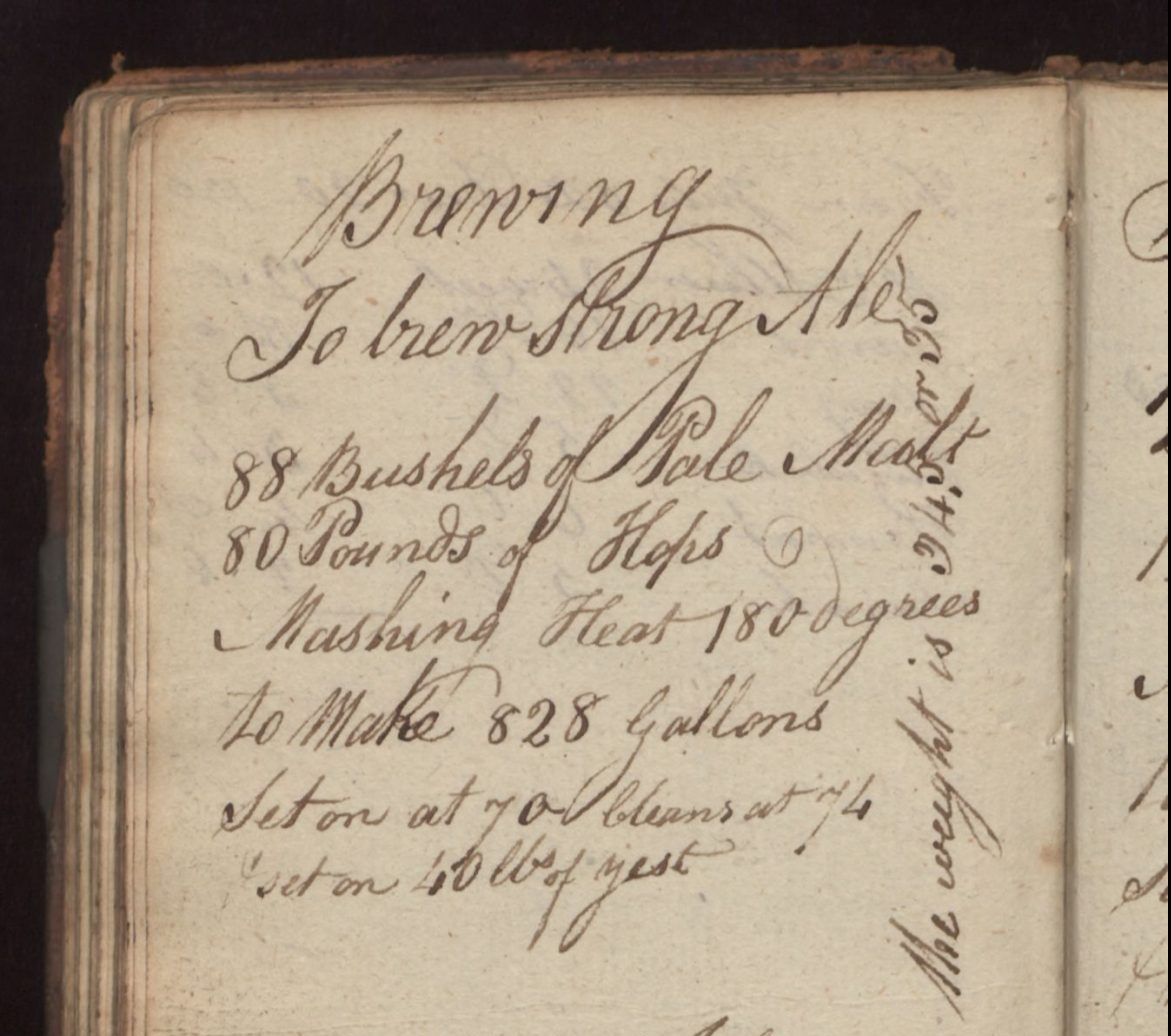

Our Archives Assistant Denise Anderson explored the Szathmary collection to create the perfect cherry pie. Below is the recipe, along with Denise’s step-by-step guide on what she did to create what is sure to be the best dessert at your next Thanksgiving.

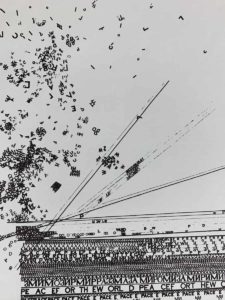

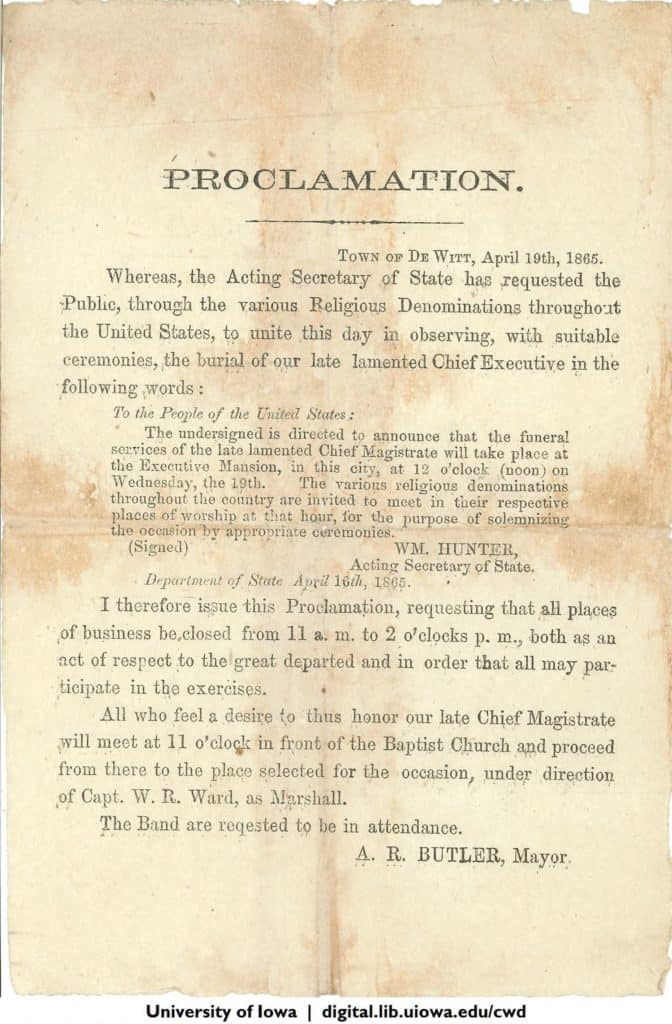

Time to make a Betty Crocker fresh fruit (in this case cherry) pie recipe, found on page 10 in All About Pie from the Szathmary Recipe Pamphlets collection.

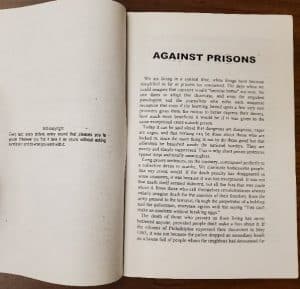

The original recipe, pictured above calls for the following ingredients for a 9″ pie:

*1 to 1 1/2 cups sugar

*1/3 cup GOLD MEDAL Flour

*1/2 tsp. cinnamon

*4 cups fresh fruit (cherries)

*1 tbsp. butter

*Pastry for 9″ two-crust Pie

Taking this base recipe, I have made a few adjustments to make the perfect pie (which you see below).

I like the look of an ample pie, so I used a nine-inch, glass, deep-dish pie pan and I increased the 4 cups of fruit called for to 6 1/2 cups, which then required adjustments to the other ingredients; adjustments provided below.

Frozen tart cherries are also available, but if you use fresh cherries, which are ripe around the Fourth of July, you will wash, sort out blemishes and remove the stones. Preserve the juice in a separate measuring cup.

In a pan on the stovetop, combine 3/4 cup cherry juice, 5 T. small pearl tapioca, 2 1/2 cups sugar, 2 T. water, 1 T. fresh lemon juice, 1/2 t. almond extract. Cook and stir this on medium-low heat until it thickens, and then boil it for one minute. Remove from heat and set it aside for 15 minutes. Tapioca can be difficult to locate on grocer’s shelves. You might have better luck finding quick cooking tapioca granules at a natural grocers.

My grandmother Sylvia taught me to make pie crust using the Crisco Single Crust recipe printed on the label. This recipe is included in Crisco’s American Pie Celebration, from the Szathmary Recipe Pamphlets collection. Because I have a penchant for oversized pies, I tripled the recipe and cut the dough in half for top and bottom crusts, ensuring there was no difficulty rolling the dough to fit.

Crisco Single Crust recipe:

Combine 1 1/3 cups flour and 1/2 t. salt.

With a pastry cutter, work 1/2 cup Crisco into the mix evenly.

Sprinkle in 3 T. water, not all in one spot, and mix it in.

Roll the dough into a ball and then evenly flatten it a bit in your hands until it is a thick disk. Sprinkle flour onto your countertop or pastry cloth and smooth it around in a circle with your palm. Gradually roll the dough into a circle using a rolling pin, working from the center outward in different directions until you reach a size that is two inches larger than your pie pan if it were placed on top of the dough upside down. As you roll, sprinkle more flour onto the dough if it begins to stick. Gently drape one half of the dough circle over the other half, and then again (quartered) so it may be easily picked up and positioned in the pie pan. Now follow these steps with the top crust, and when it is draped into a quarter, cut slits through the crust for ventilation. Set the quartered top crust aside for a moment, still folded.

Pour the cherries into the bottom crust, and then pour in the thickened cherry juice. Dot the top of the cherries with 2 T. of butter cut into small pieces. With a coffee cup of water next to the pie, dip your fingers into the water and run them along the rim of the bottom crust until you have dampened the entire rim, leaving the excess dough hanging over the sides. This moisture will help seal the two crusts together. Place the quartered top crust in place, and gently unfold it to cover half, and then the whole pie. Excess crust from both the top and the bottom are draped over the rim. With your thumb and index finger, work around the rim, pinching the dough slightly to build up the rim and make an interesting design. Use a knife to trim off the excess dough, cutting below the fluted edge.

Cut 3 or 4 strips of aluminum foil to wrap loosely around the rim of the pie, so it won’t burn. Overlap the pieces of foil and crimp them together a bit with your fingers to hold them together, without pressing into the dough. Line the bottom of the oven with aluminum foil before preheating to 425 degrees. Bake for one hour on the center rack, removing the foil strips after 45 minutes.