“From the Classroom” is a series that features some of the great work and research from students who visit our collections. Below is a blog by Elizabeth McKay from Dr. Jennifer Burek Pierce’s class “History of Readers and Reading” (SLIS:5600:0EXW)

Business, Beer, and the Bible: The Case of the Maude’s Commonplace Books

By Elizabeth McKay

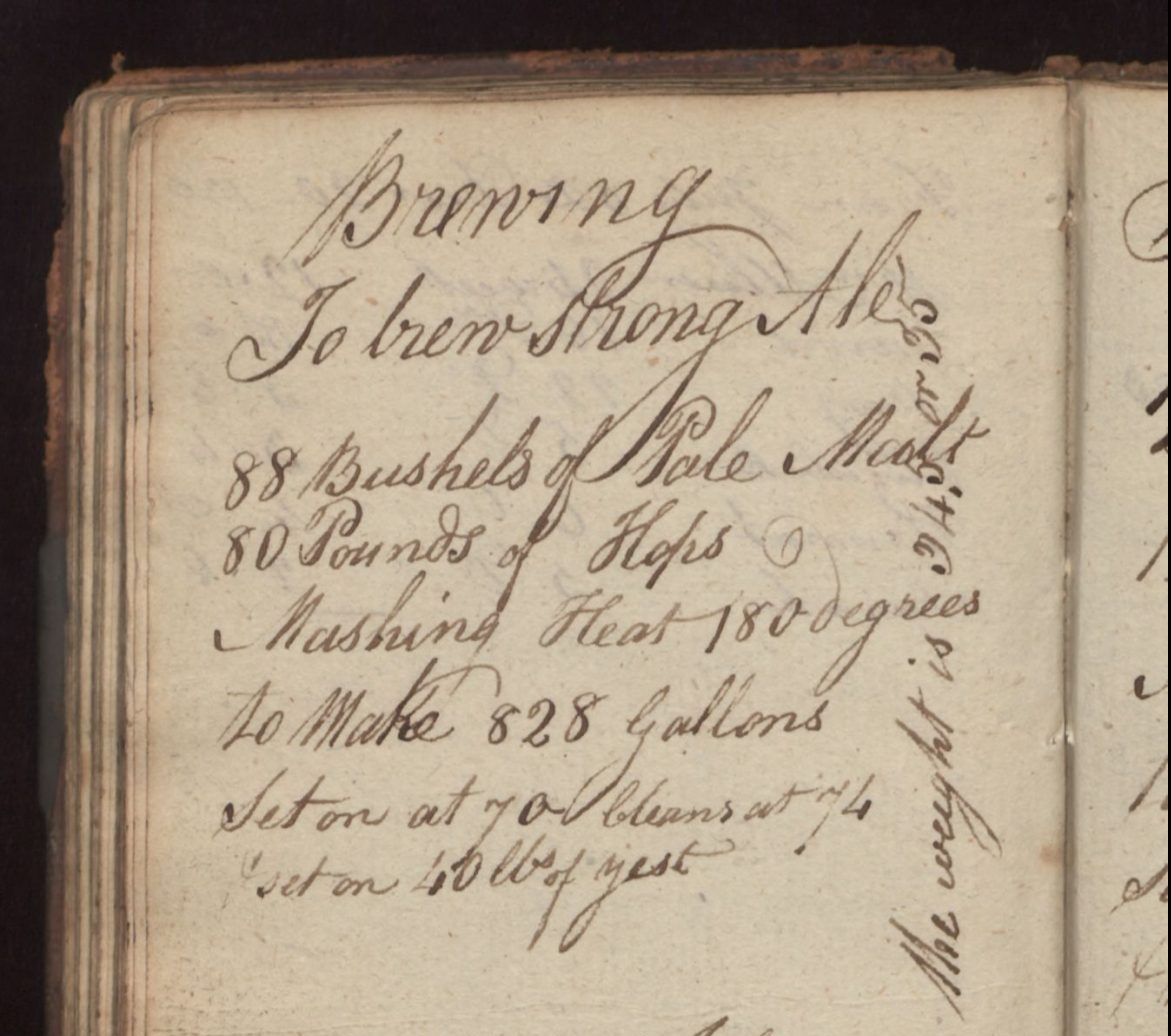

William Maude was born in 1787 in England, and his son John emigrated to New England. There he worked in cotton mills before moving to Delaware County, Iowa. These notebooks found their way into Iowa’s Special Collections Culinary Manuscripts collection because of the recipes they hold. Maude recorded many recipes for beer from Morrice’s Treatise on Brewing which was published in 1802. There are more than just beer recipes, though. There are also recipes for ink, medical recipes for coughs and colds, and even a tongue-in-cheek recipe for lovesickness.

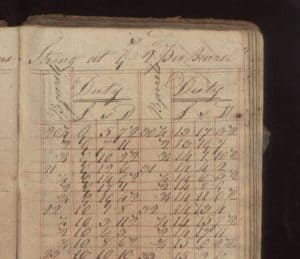

However, the primary use of these books pertained to William Maude’s job in the customs business in England. He used the notebook for calculations and charts that he would’ve copied into an official record. He also included useful reference material for work and notes on bookkeeping. Besides William Maude’s business notes, these “commonplace books” were used by his family for several generations. They continued to be used as a space for quick calculations or sometimes to practice handwriting or jot down a note.

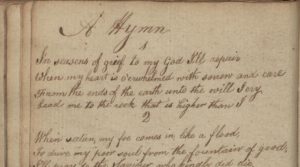

Amidst its casual usage, the Maude family kept a record of important moves and new jobs. Other meaningful additions are a thorough scriptural index (probably copied down out of a book or periodical for the Maude’s use), hymns, fables, jokes, as well as the recipes mentioned above. These books seemed to straddle the line between holding valuable reference information and being used as a kind of collective notebook. While some entries are quick and messy, others are written in very clear and legible hand— designed to be referenced again and again.

It is these entries designed to be referenced that makes these volumes “commonplace books.” The term comes from a renaissance pedagogical practice of recording quotes from important works under specific sections in a notebook for memorization and reference. Scholar Ann Moss describes commonplaces as “purpose-built instruments for the collection, classified storage, and recycling of knowledge.” Commonplace books in the renaissance were defined by their “heads” that coincided with strict rules for filing quotations under their proper category. By the time the Maude family is writing, this practice is not strict at all. Today, the term “commonplace books” is used even more loosely. A commonplace book can be any sort of compiling notebook with no organizational structure. In the case of the Maude’s books, these notebooks were not used to organize their reading. Rather, they are at times just the paper at hand, at times a business record, and, occasionally, a place to store a hymn or a story. In fact, these notebooks most resemble commonplace books of old in one particular entry: the scripture index.

In the 19th century, manuals, indexes, and all varieties of textual navigation tools were published as appendixes to bibles or in separate volumes. These indexes were highly valued as reference tools to help understand the Bible. Even as the pedagogical tradition of commonplacing drifted into the past, this organizational practice remained strong as a way to understand the Bible in terms of themes. One of the Maude’s writes above the thorough index: “Select Scriptures arranged under their respective heads” — harkening to the language of an older type of commonplace book.

While the history of what are called “commonplace books” is rooted in educational practice and the ideal of knowledge organization. Its story throughout history is marked by a gradual decline of the ideals of organization, and the commonplace book moves more firmly into the realm of “miscellany.” This also may strike us as the story of many of our own notebooks. Beginning a new notebook with the highest of intentions, by the end, the notebook has taken on a life of its own, collecting various bits and pieces of our experiences. This seems to be the case with William and John Maude’s two volume set of commonplace books. Toward the beginning of the first volume, there is a page that reads “Contents” at the top. This attempt to categorize the contents seems to have never reached fruition— the page remains empty. The result is a delightfully messy notebook showing many facets of the Maude’s lives in the early 19th century.

Cited:

Moss, Ann, “Commonplace Books.” In Brill’s Encyclopaedia of the Neo-Latin World. Craig Kallendorf, Editor. <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/9789004271296_enlo_B9789004271012_0019>

Images from Iowa Digital Library

Further Reading on Commonplace Books:

Allan, David. Commonplace Books and Reading in Georgian England. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Finnegan, Ruth, Why Do we Quote? The Culture and History of Quotation. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2011.

Morrice, Alexander. A Treatise on Brewing: Wherein Is Exhibited the Whole Process of the Art and Mystery of Brewing the Various Sorts of Malt Liquor; with Practical Examples upon Each Species. Knight and Compton, 1802.

Moss, Ann. Printed Commonplace-Books and the Structuring of Renaissance Thought. Oxford University Press, 1996.