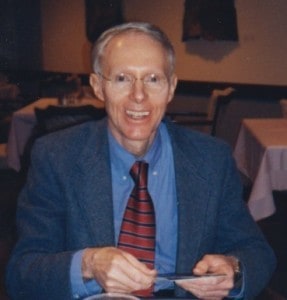

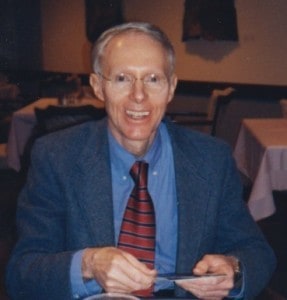

My mentor and friend Bob McCown, retired Head of the Special Collections Department in the University of Iowa Libraries, died on March 31st of this year. To remember Bob on what would have been his 76th birthday–November 21st–I share the eulogy I gave at his memorial service last spring.

Robert A. McCown (1939-2015)

Bob McCown was the first person I met in Iowa when I came for my job interview in 1992. On that April day twenty-three years ago, he was waiting at the bottom of the escalator in the Cedar Rapids Airport holding a sign that read: “Iowa Women’s Archives.” I was full of wonder about this new place that might become my home—amused at the scale of the airport, and charmed by the fact that we were driving past cornfields as soon as we left the parking lot. All during that drive to Iowa City, Bob told me about the history of Iowa—how it was settled, the Mormons who passed through with their handcarts, and other stories I have long since forgotten. What stayed with me was the sense of this kind, soft-spoken man who had such deep knowledge of and affection for his home state.

Bob was Head of the Department of Special Collections at that time. He had earned a master’s degree in history from the University of Iowa in 1963, taught high school history for a few years, and earned his library degree from Illinois before returning to Iowa in 1970 for a position in the University Libraries.

Bob was hired as Manuscripts Librarian at a time when the new fields of social history, ethnic history, and women’s history were emerging. He began traveling across Iowa in the early 1970s, intent on acquiring sources that would make this new scholarship possible. But the recent student demonstrations in Iowa City had roused suspicion about the University of Iowa. So Bob shined his shoes, cut his hair, and put on a coat and tie to allay the fears of outstate residents. In his quiet and considerate way, he tried to persuade potential donors of the significance of their papers to history. He modeled his collecting on progressive institutions such as the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. In addition to the usual political papers, he sought the records of environmental groups, social action organizations, and women. Sometimes he was successful, other times not. But the seeds he planted in those early years continued to bear fruit five years later, ten years later, or even two or three decades later.

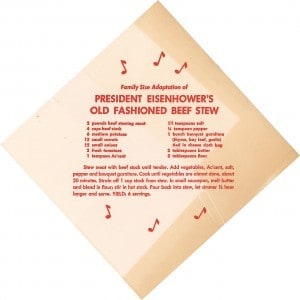

Over the decades, Bob built a solid foundation for the study of Iowa history. He acquired farmers’ diaries, Civil War letters, merchants’ account books and railroad records. He solicited manuscripts by Iowa authors, and built on the already strong literary holdings of the department. Special Collections has continued to build on the groundwork Bob laid over three decades.

Of course, collection development was not Bob’s only work. He organized symposia, published articles, and edited the journal Books at Iowa and the newsletter of the Ruth Suckow Association. (He had a particular affinity for Suckow, not least because she hailed from his hometown of Hawarden.) Bob contributed to the archival profession through his service on the Iowa Historical Records Advisory Board and his longtime involvement with the Midwest Archives Conference. And he brought history home by presenting talks on a various topics to local organizations and clubs.

But I keep coming back to Bob’s efforts to preserve Iowa history, because I believe that was his greatest achievement. Bob’s vision of what Iowa history could be led him to seek out those aspects that that had been neglected by archivists and historians alike. When women’s historians began asking for sources in the ‘70s, Bob combed the Special Collections stacks searching for documents by and about women.

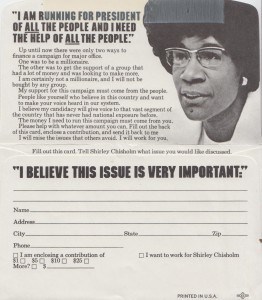

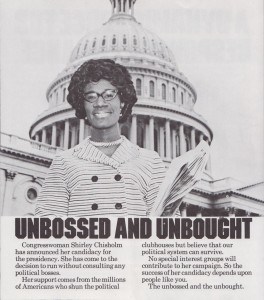

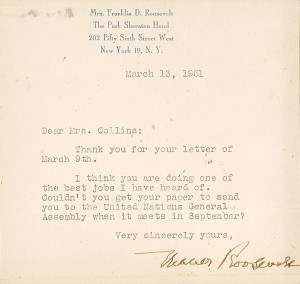

And then he went a step further. He began consciously seeking out women’s history. He acquired the papers of Minnette Doderer, the League of Women Voters of Iowa, and the Iowa Nurses Association. He had the foresight to contact Mary Louise Smith before she rose through the ranks to become the first female chair of the Republican National Committee; when Smith finished her term she made good on her promise to send her extensive papers to the University of Iowa, about which Bob was especially proud.

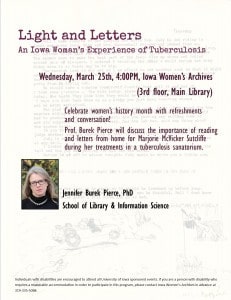

When Louise Noun suggested in the early ‘70s that the University Libraries beef up its holdings of women’s historical writings, Bob arranged to meet with her in Des Moines, initiating a relationship that would eventually lead to the creation of the Louise Noun – Mary Louise Smith Iowa Women’s Archives at the University Libraries.

Bob’s careful plans for the archives, together with the papers of women politicians, artists, nurses, and lawyers he had gathered over two decades formed the core of the Archives when it opened in 1992. Equally important was the support and guidance he gave me.

When I began work as the first curator of the Archives, I was pretty green, especially when it came to donor relations and collection development. But Bob was a great supervisor! He taught me everything, from how to write a letter and make a cold call to a potential donor, to the more mundane details—like how to get a car from the motor pool and fill out the countless travel forms. And then there were the finer points he’d learned from his own experience. For example, when you’re out in the field and driving a University vehicle, do not have dinner at a supper club—even if it’s the only restaurant in town—because someone is sure to notice the car with the University seal parked out front and report this “inappropriate” activity by a state employee.

Bob guided me with gentle nudges and taught me by example, as when we visited donors together. Our weekly meetings always included some family talk, a shared laugh or two, and some musings about the topic of the day. I was grateful to have such an empathetic boss who treated me with respect and was interested not only in what I did on the job but in my family and my life outside work. Through the years I worked with Bob, I learned a great deal from him, not only about history, but about how to treat one’s colleagues and staff.

Bob contributed immeasurably to Iowa history but also to the lives of those of us fortunate enough to be around him. Bob’s knowledge of Iowa history was broader than the Missouri, deeper than the Mississippi, and a lot more solid than the Loess Hills. Iowa history is richer for his contributions. And all of us who knew him are richer for his friendship and his affection.

–Kären M. Mason, April 4, 2015