This post, by Christina Jensen, appeared on the Iowa Women’s Archives Tumblr this summer, and has since been featured on NBC news.

On June 28th, 1914, Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo by Yugoslav nationalist Gavrilo Princip. One month later, war broke out across Europe between two alliance systems. Britain, France, Russia, and Italy comprised the Allied powers. Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire constituted the Central powers. As war raged abroad, the U.S. wrestled with the politics of neutrality and intervention. In April of 1917, President Wilson was granted a declaration of war by Congress. The United States thus officially entered the conflict alongside Allied forces.

To mark the occasion of the World War I centennial, we’re remembering Iowa women whose lives were shaped by the war.

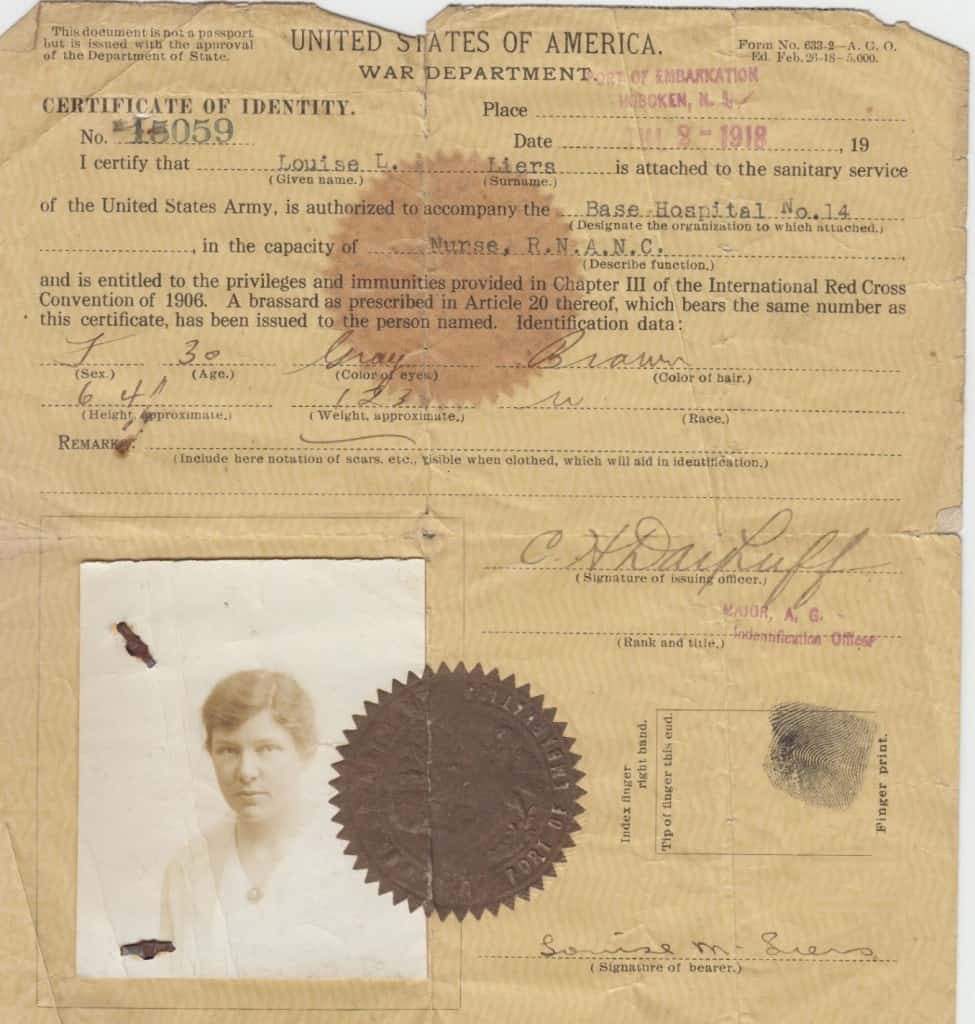

One such woman was Clayton-native Louise Marie Liers (1887-1983), an obstetrics nurse who enrolled in the Red Cross and served in France as an Army nurse.

Before her deployment, however, Liers was required by the American Red Cross to submit three letters “vouching for her loyalty as an American citizen.” All nurses, regardless of nationality, were similarly required to provide three non-familial references testifying to this effect. While questions of loyalty and subversion are exacerbated in any war, America’s domestic front was rife with tension driven by geography, class, and ethnicity that raised fears and stoked national debate in the years leading up to America’s engagement in the Great War.

Arriving in 1918, Liers was stationed in the French town of Nevers where she treated wounded soldiers. During this time Liers wrote numerous letters home to her parents and brother describing her duties and conditions of life during the war.

In a letter to her brother, featured below, Liers described her journey to France from New York City, with stops in Liverpool and Southampton.

When Liers arrived in 1918, Nevers was only a few hours away from the Allied offensive line of the Western Front. She was assigned to a camp that served patients with serious injuries and those who required long-term care. Liers noted in a 1970 interview that, by the end of the war, as fewer patients with battle wounds arrived, her camp began to see patients with the “Asian flu,” also known as the 1918 influenza outbreak that infected 500 million people across the world by the end of the war.

In letters home, and in interviews given later, Liers described pleasant memories from her time in service, including pooling sugar rations with fellow nurses to make fudge for patients. Nurses could apply for passes to leave camp and Liers was thus able to visit both Paris and Cannes. In an interview Liers recalled that, serendipitously, she had requested in advance a leave-pass to travel into town for the 11th of November, 1918. To her surprise, that date turned out to be Armistice Day, and she was able to celebrate the end of the war with the citizens of Nevers.

“…devised such tortures and called it warfare…”

Along with her cheerier memories, however, Liers’s papers also describe the difficulties of caregiving during war. She described Nevers as a town “stripped of younger people” due to the great number of deaths accrued in the four years of war. In later interviews Liers offered many accounts of the grim surroundings medical staff worked under, from cramped and poorly equipped conditions, to unhygienic supplies, such as bandages washed by locals in nearby rivers, which she remembered as “utterly ridiculous from a sanitary standpoint…they were these awful dressings. They weren’t even sterilized, there wasn’t time.” Due to the harsh conditions and limited resources, nurses and doctors gained practical knowledge in the field. Liers recalled frustrating battles to treat maggot-infected wounds before the nurses realized that the maggots, in fact, were sometimes the best option to keep wounds clean from infection in a field hospital.

On a grimmer note, Liers wrote to her parents the following:

“As I have told you before, the boys are wonderful- very helpful. When I see their horrible wounds or worse still their mustard gas burns or the gassed patients who will never again be able to do a whole days work- I lose every spark of sympathy for the beast who devised such tortures and called it warfare- last we were in Moulins when a train of children from the devastated districts came down-burned and gassed- and that was the most pitiful sight of all.”

By the time the “final drive” was in motion, Base Hospital No. 14 was filled with patients to nearly double capacity, and doctors and nurses had to work by candlelight or single light bulb. Liers’ wartime service and reflections suggest a range of emotions and experiences had by women thrust into a brutal war, remembered for its different methods of warfare, inventive machinery, and attacks on civilian populations.

Liers worked in France until 1920, and her correspondence with friends and family marks the change in routine brought on by the end of the war. With more freedom to travel, Liers and friends toured throughout France, and like countless visitors before and after, Liers describes how enchanted she became with the country, from the excitement of Paris to the rural beauty of Provence.

Following the war, Liers returned to private practice in Chicago, and later Elkader, where she was regarded as a local institution unto herself, attending over 7,000 births by 1949. She was beloved by her local community, which gifted her a new car in 1950 as a sign of gratitude upon her retirement.

Want more? Visit the Iowa Women’s Archives! We’re open weekly Tuesday-Friday, 10:00am to noon and 1:00pm to 5:00pm.

A list of collections related to Iowa women and war can be found here.