This post by IWA Graduate Assistant, Heather Cooper, is the first of a series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives’ collections. The series will continue weekly during Black History month, and monthly throughout 2020.

The Grace Morris Allen Jones collection at the Iowa Women’s Archives consists of only one folder, but inside it you will find the history of three generations of remarkable African American women. Jones was born in Keokuk, Iowa in 1876 and grew up in Burlington, where she would later establish the Grace M. Allen Industrial School for African American students. After her marriage to Dr. Laurence Clifton Jones in 1912, the couple moved to Piney Woods, Mississippi, where together they built and taught at the Piney Woods Country Life School. Jones maintained contact with family and friends in Iowa and, in 1927, she wrote and published an article about her family history in The Palimpsest, a magazine published by the State Historical Society of Iowa.

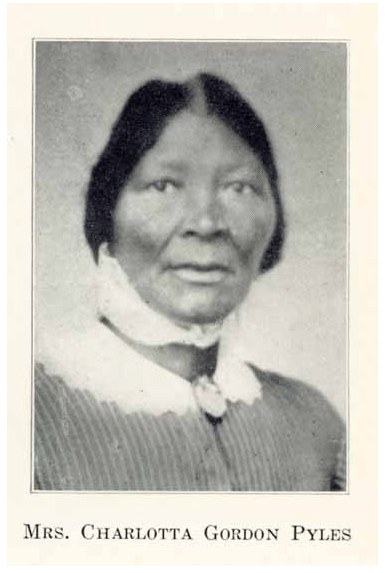

In “The Desire for Freedom,” Jones tells the story of her family’s journey from slavery to freedom in the 1850s. Jones’ grandmother, Charlotta Pyles, was enslaved by the Gordon family on a large plantation in Kentucky, along with her twelve children. Her husband, Harry Pyles, was a free man, but under the laws of slavery he had no legal authority to protect his own wife and children. When she was fifty-four years old, Pyles was granted her freedom, along with most of her kin, and they made the arduous journey from Kentucky to free territory just as winter set in. The group, which ultimately settled in Keokuk, Iowa, included Charlotta and Harry Pyles, eleven of their children, and five of their grandchildren. The family lived in a large brick house, built by Harry Pyles, and belonged to the First Baptist Church of Keokuk. It was there that Charlotta and Harry Pyles were legally married in 1857, a right denied to them under slavery, where husbands, wives, and children could be separated at the whim of slave owners and traders.

But, as Jones describes, freedom did not bring an end to heartache, for Charlotta Pyles was forced to leave behind one of her sons, Benjamin, and two of her sons-in-law. Pyles was determined to purchase the freedom of her sons-in-law, who had wives and children that needed them. Clearly aware of the antislavery movement and fugitive slave activists like Frederick Douglass who wrote and spoke publicly about their experience, Pyles traveled to the East Coast to engage audiences and raise the necessary money. Speaking in major cities like Philadelphia and New York, she gained the attention of prominent figures like Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Lucretia Mott. Immensely proud of her grandmother’s bravery and commitment, Grace Morris Allen Jones wrote,

It was a difficult task for a poor, ignorant woman, who had never had a day’s schooling in her life, to travel thousands of miles in a strange country and stand up night after night and day after day before crowds of men and women, pleading for those back in slavery. So well did she plead, however, that in about six months she had raised the necessary three thousand dollars, returned to Iowa, thence to Kentucky where she bought the two men from their owners, and reunited them with their families.

Jones rightly noted that “the spirit of Charlotta Pyles found worthy expression in her children and grandchildren,” who made their own remarkable impacts on Iowa and the nation. The Pyles family is a reminder of the long history of African American settlement, community-building, and activism in the Hawkeye state. Check out the Grace Morris Allen Jones papers to learn more about the family, as well as Jones’ work in Piney Woods

In addition to the Grace Morris Allen Jones papers, this post references Betty DeRamus, Forbidden Fruit: Love Stories from the Underground Railroad (New York: Atria Books, 2006), 109-123. A copy is available at Iowa Women’s Archives.