The following is written by Museum Studies Intern Joy Curry.

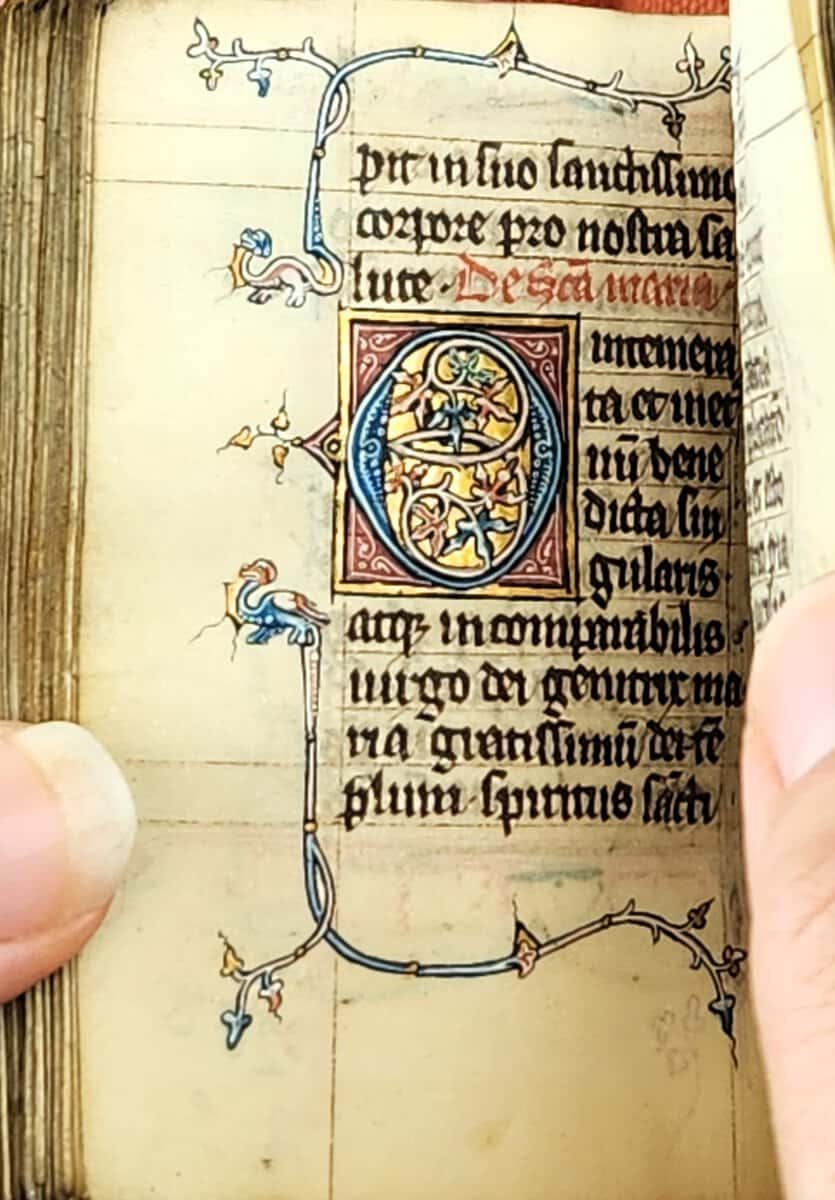

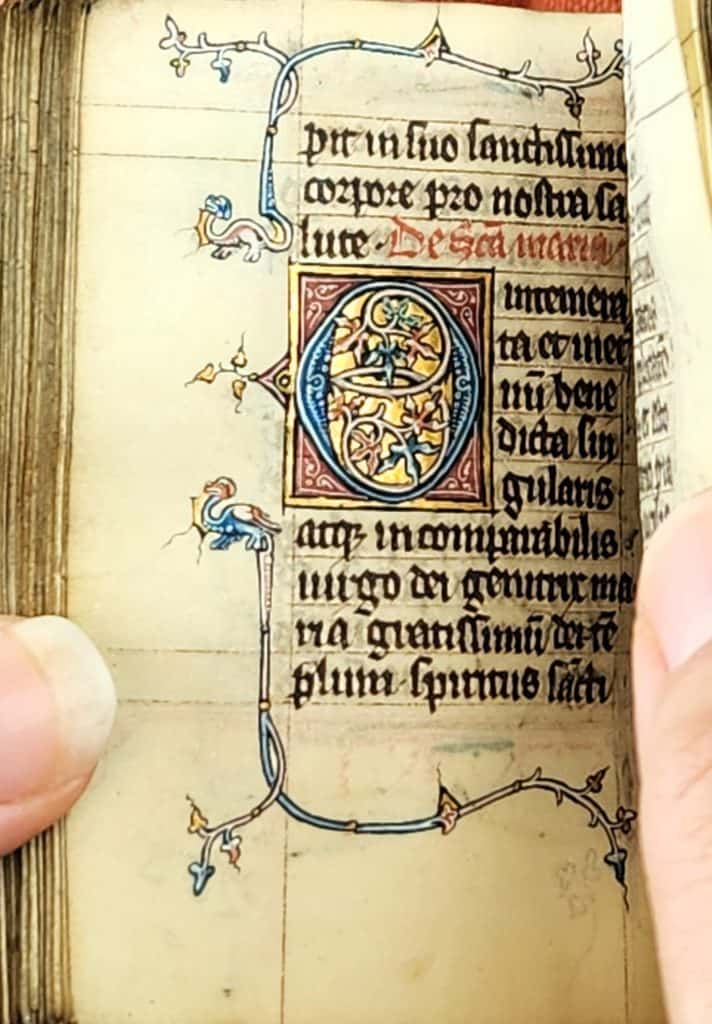

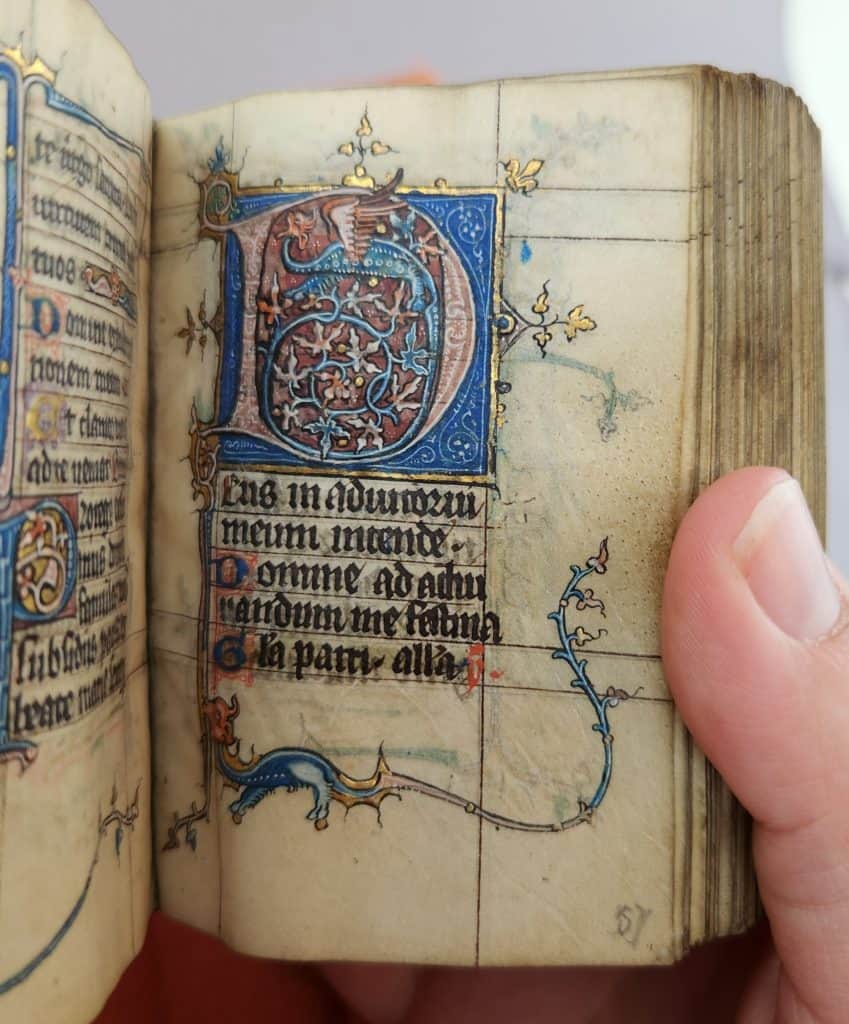

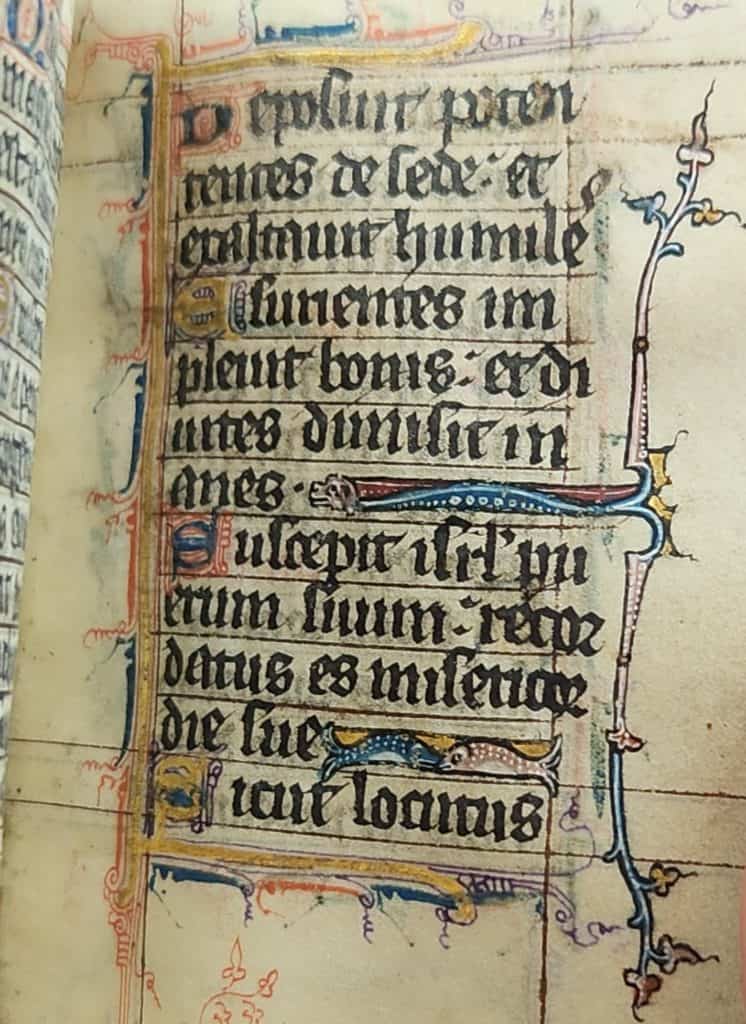

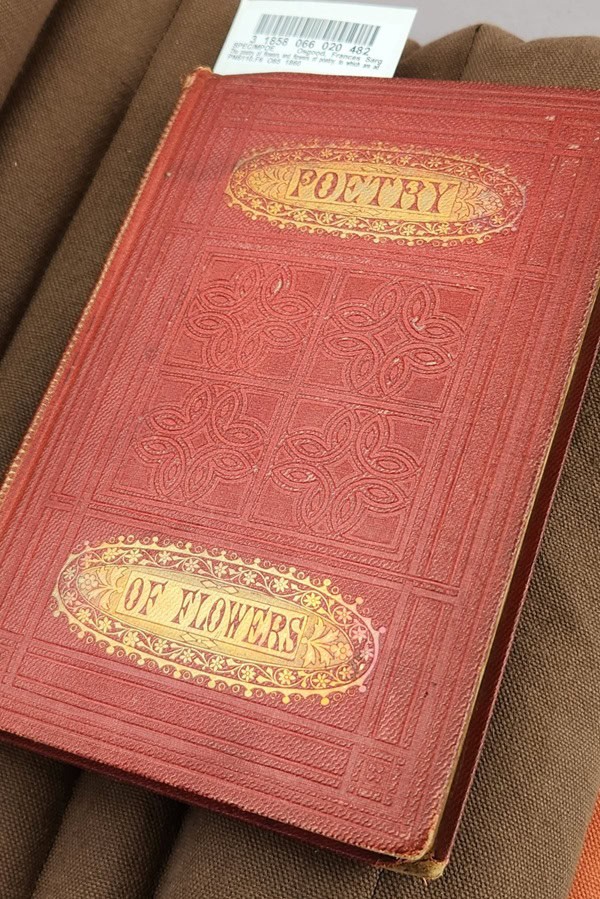

This 14th-century book of hours may be tiny, but it is jam-packed with beasts, ranging from fish to lions to feathered dragons. It’s a marvel that so much of the art has survived, especially since the book is missing 19 miniatures. Fortunately for us, the illustrator incorporated figures throughout the letters, lines, and margins of the book.

According to the seller’s information, the illustrator of this manuscript also worked on the Ghent Psalters (Bodleian MSS Douce 5-6). We recognize them by their decorative line-fillers, dragons in the margins, and finely-painted expressive faces. The illustrator decorated our manuscript for use in the diocese of Thérouanne. As a book of hours, the reader would have used it for religious meditations and devotions.

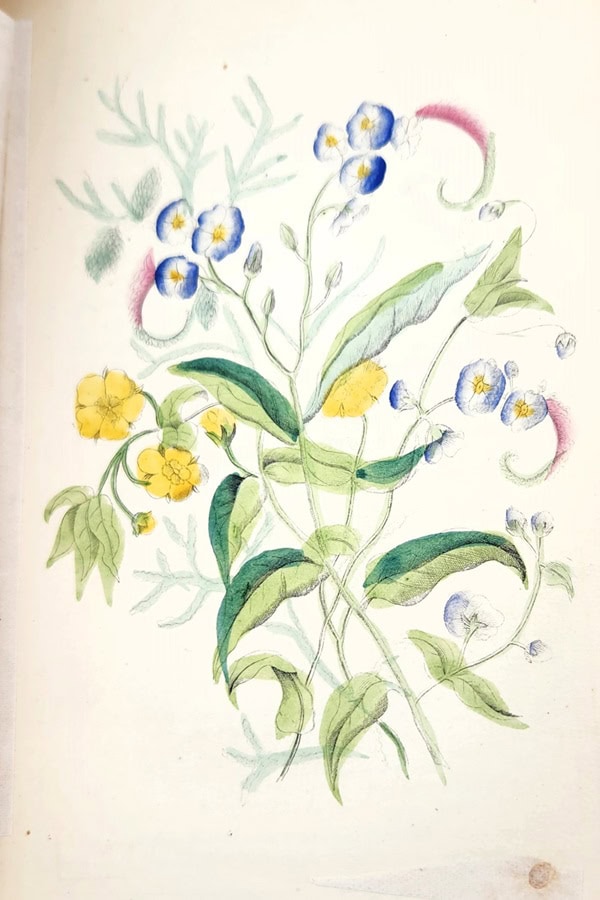

In that context, it may seem strange that the art decorating the book is so unsacred. The marginal creatures don’t create an orderly, contemplative scene; they attempt to bite letters and borders, they smack into one another, and they vomit vines that curl around the text block.

As Michael Camille has argued, these chaotic creatures don’t detract from the religious purpose of the text. By mixing up important medieval categories—man and beast, sacred and profane—the art plays with taboo and makes a visual contrast between the holy interior of the text and the wild, disorderly margins. As Elaine Treharne pointed out, art that encroached on the text block, like the decorative line-fillers, still contributed to the order by maintaining a balanced writing grid

Of course, these small illustrations also provided an opportunity for artists to show off their skill and joy in their work. Even though the book of hours is tiny, the illustrator still took care to show the scales on the fish, shading on the leaves, and feathers on the wings. Whatever its exact purpose, this art shows impressive dedication to the craft.

Come visit Portable Book of Hours, use of Thérouanne (xMMs. Bo13) today.

Further Reading:

Camille, Michael. Image on the Edge : The Margins of Medieval Art. Reaktion Books, 1992.

Treharne, Elaine. Perceptions of Medieval Manuscripts: The Phenomenal Book. 1st ed., Oxford University Press, Incorporated, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192843814.001.0001.

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Douce 5: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/ffa96f42-fde8-4f82-93e5-0c645f7f1b94/ Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Douce 6: https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/4a0c575c-0cad-4dd2-8fd4-a6689c0ae1e8/