The following is written by M Clark, instruction and reference graduate assistant for Special Collections and Archives

While Pacific Island cultural experiences are far and few in Iowa, Special Collections and Archives is the proud host of a number of rare and highly regarded publications by prolific Pacific Islander creators or about the rich histories and cultures of the islands. Here is a look at just 10 items from the collection you can come see.

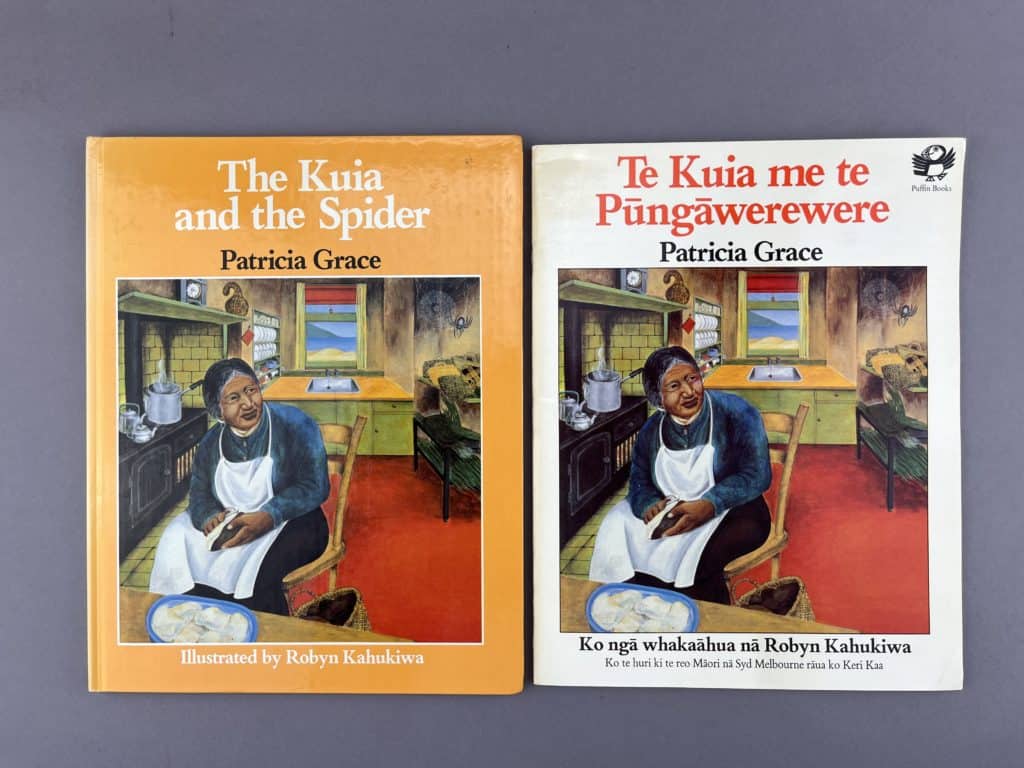

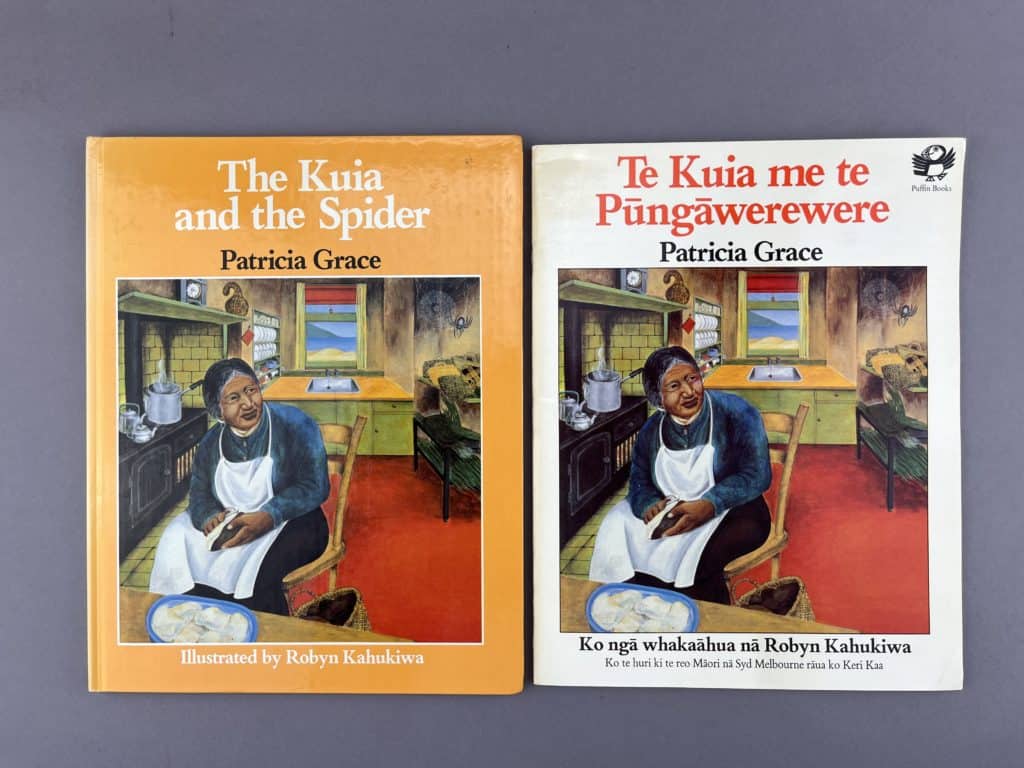

Te Kuia me te Pungawerewere (The Kuia and the Spider) by Patricia Grace.

X-Collection FOLIO PZ5.G73 K853 1981

Patricia Grace’s Māori children’s book Te Kuia me te Pungawerewere (its English language version titled The Kuia and the Spider) is the tale of a Kuia, meaning elderly woman or grandmother in English, and a spider who share a kitchen and are in a constant playful argument of who is better than the other. Patricia Grace, a former school librarian herself, is a famed Māori writer of novels, short stories, and children’s books. The publication of this book in both English and te reo Māori, the Māori language in the 1980s was of immense importance to language revitalization efforts following the presentation of the Māori Language Petition in 1972 and the officialization of Māori Language Week in 1975. Te Kuia me te Pungawerewere was awarded New Zealand Picture Book of the year in 1982 and remains a beloved story by Māori educators and families.

Tongan Ngatu.

MsC 913

Ngatu, or ngatu hingoa, in the Tongan language refers to the elaborately decorated tapa bark cloth tapestries of Tongan cultural significance. The art of ngatu is made distinct through processes of dying, stamping, and hand painting the tapestries, though still similar to the artful practices using tapa bark cloth in other Polynesian islands. The ngatu held in Special Collections was likely created in the 1940s, during or after World War II, and includes illustrations of planes to commemorate the contribution of the Tongan Defense Force to the British war effort. The tapa, or bark cloth itself, is likely made from mulberry tree bark, commonly used in the Pacific for this exact craft. Illustrations and stamping was likely done with dyes made from saps of other native Tongan plant species, such as candlenut trees.

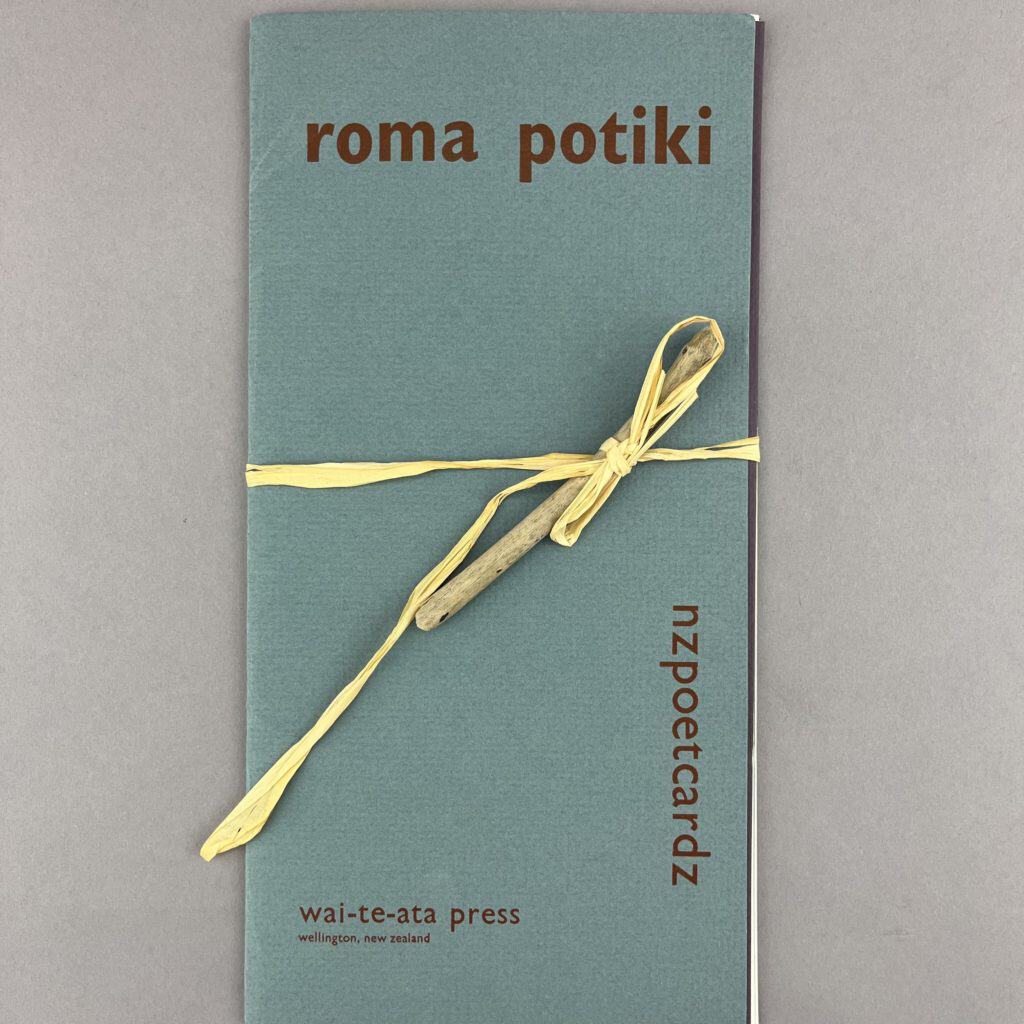

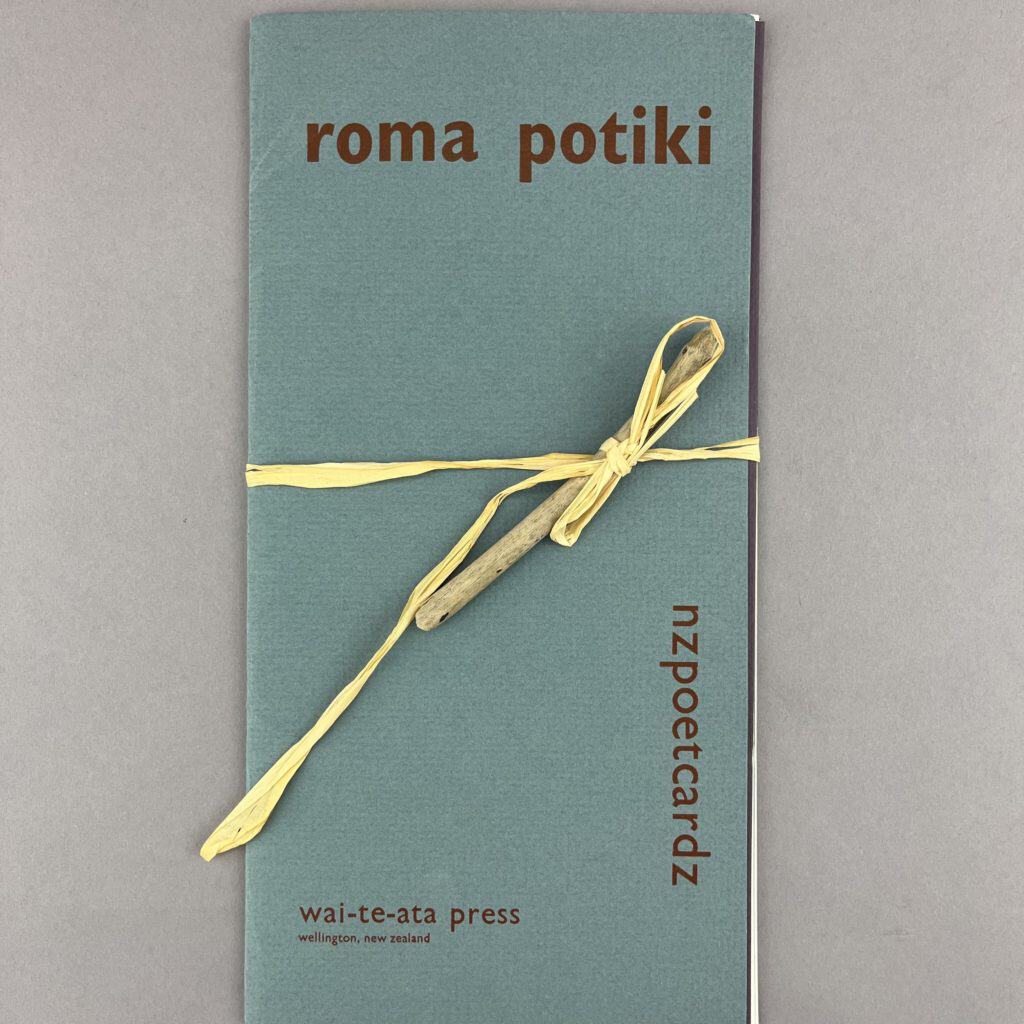

Roma Potiki by Roma Potiki.

X-Collection Folio PR9639.3.P59 R6 1996

Roma Potiki is a noteworthy contemporary Māori poet, playwright, and performer. Her self-titled collection of poetry explores themes and topics of nature, the human spirit, Māori womanhood, politicization, and the lasting effects of colonization. The poems in this limited collection were also published in her 1998 collection Shaking the Tree.

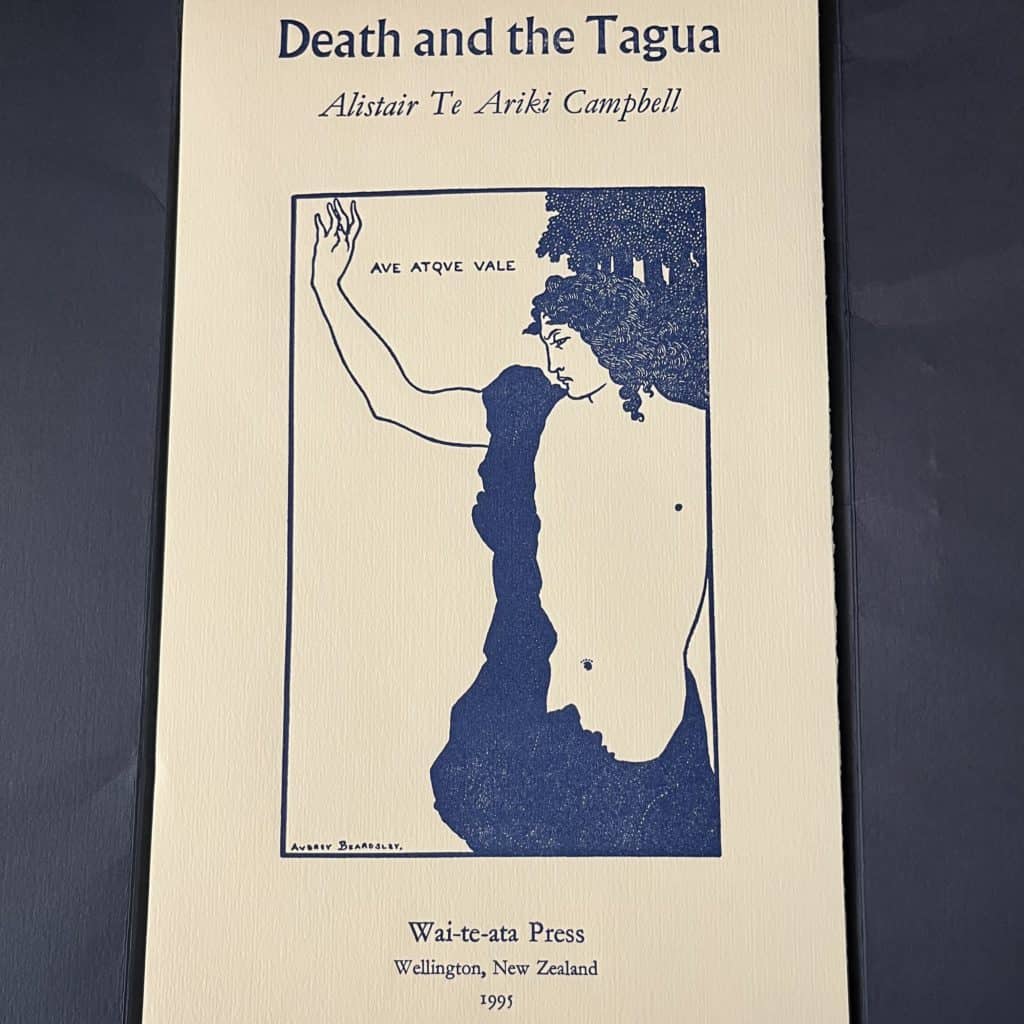

Death and the Tagua by Alistair Te Ariki Campbell.

X-Collection Folio PR9639.3.C275 D4 1995

Alistair Te Ariki Campbell is a famed New Zealand poet and playwright of Cook Islands Māori descent. This collection of poems, Death and the Tagua, is the artistic account of and response to Campbell’s own journey from Rarotonga in the Cook Islands to New Zealand via a Tagua sailing vessel, and the deaths of both of his parents in his early life.

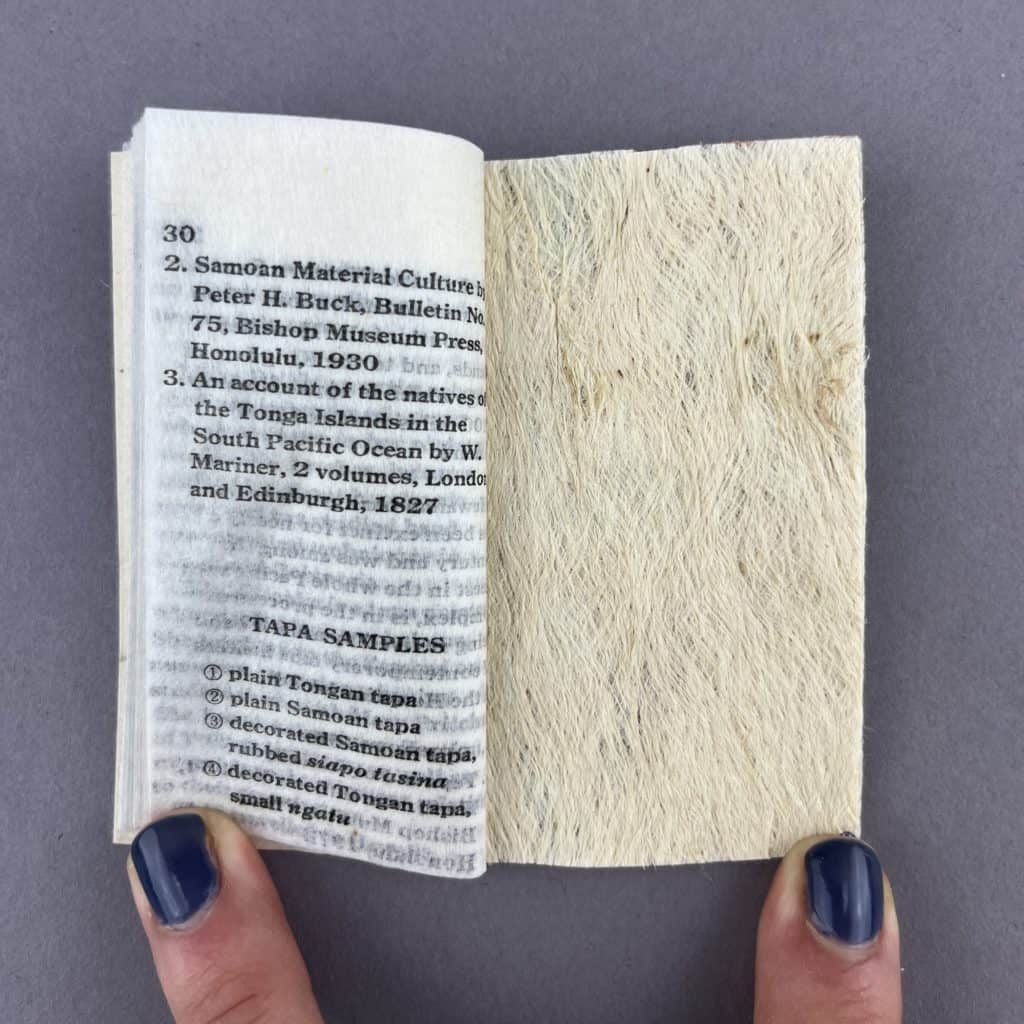

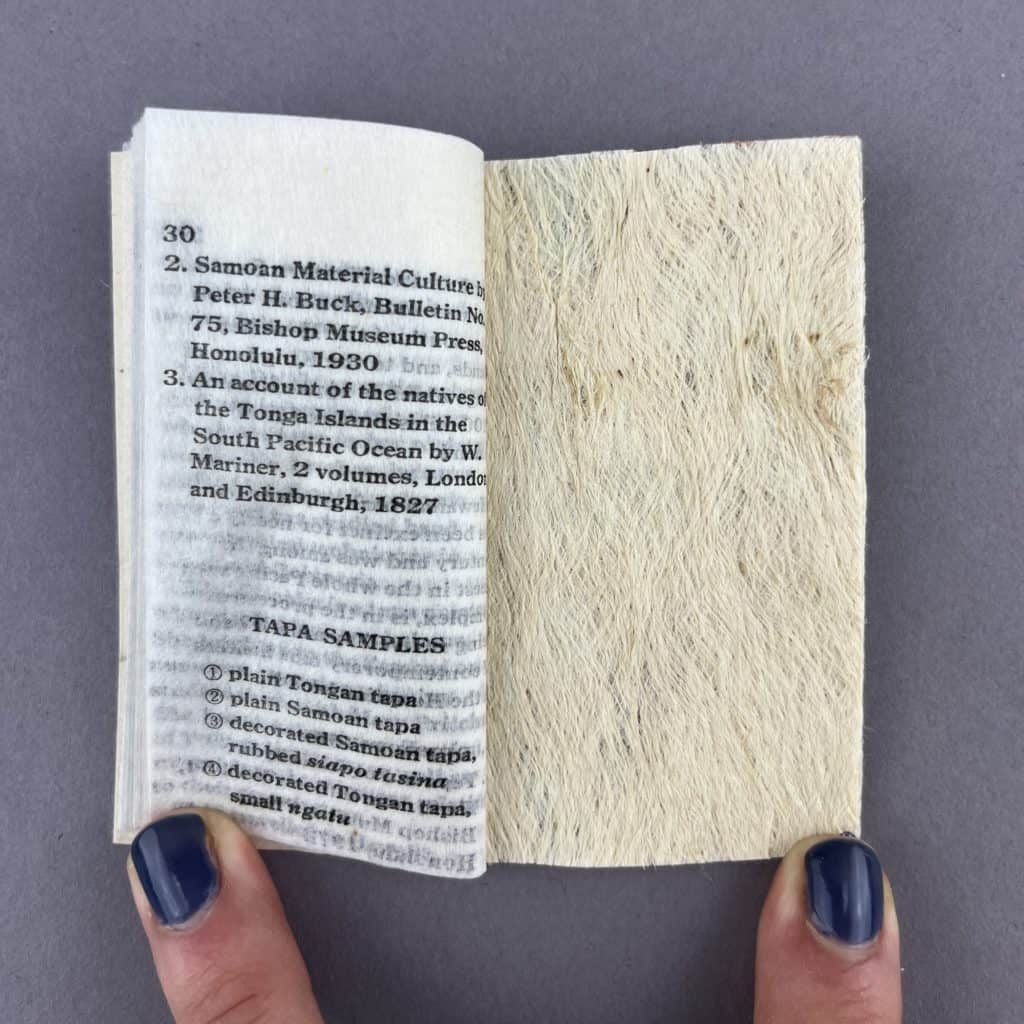

Tapa: the bark paper of Samoa and Tonga by Lilian Bell & Ulista Brooks.

Smith Miniatures Collection TS1095.S36 B45 1979

Tapa is the bark paper or cloth of Polynesian islands including Samoa and Tonga, as specifically shown in this miniature book of paper samples. The bark of mulberry trees, among other plants, is processed into a fibrous paper that is often then ornately decorated with dyes for cultural customary or celebratory purposes. In Tongan culture, these decorated tapas are called ngatu, and in Samoan culture, called siapo.

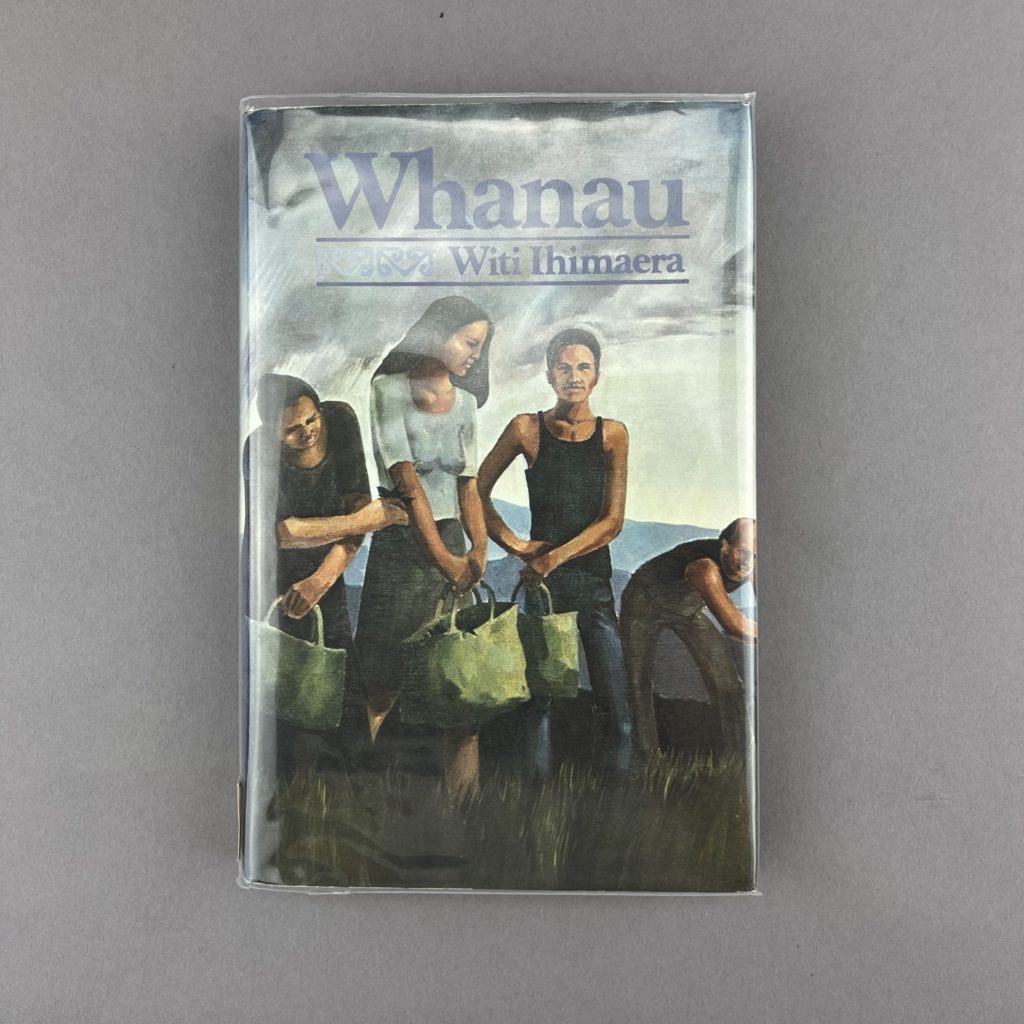

Whanau by Witi Ihimaera.

X-Collection PZ5.I35 W43 1974

Whanau, meaning family in te reo Māori, is a story of just one day in the lives of a large family living in a rural Māori village, struggling with the loss of traditional values and ways of living due to colonial pressures. It is the second work published by Witi Ihimaera, who is considered one of if not the most influential Māori writer still today. He was the first Māori writer to ever publish both a novel and book of short stories. The story takes place in the small town of Waituhi, were Ihimaera himself was raised and inspired to become a writer after seeing the erasure or mischaracterization of Māori in literature in New Zealand and globally. Our copy is signed by Ihimaera, with a note to the book’s donor, Carmon Slater, that reads “To remind you of a wonderful partnership and warm time at Tokomaru Bay when we worked on improving the self image of Māori Children.”

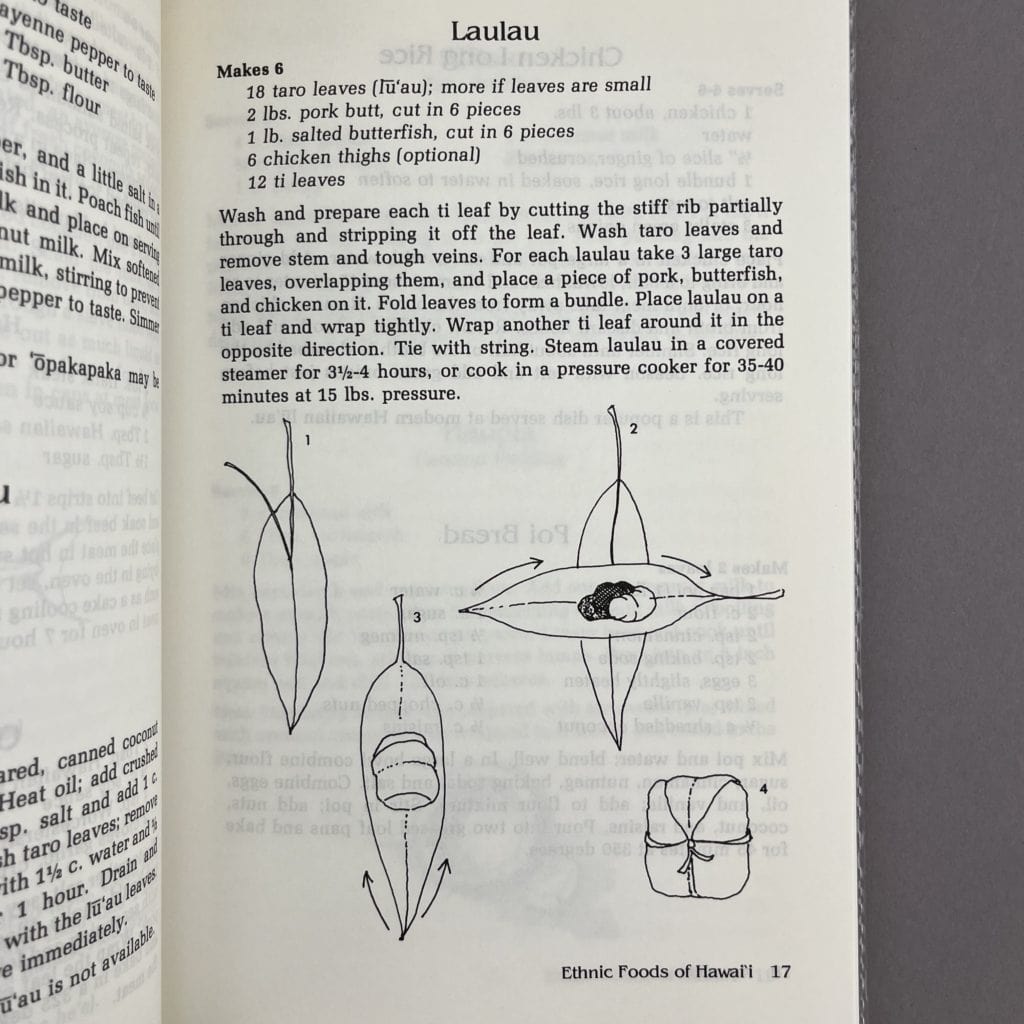

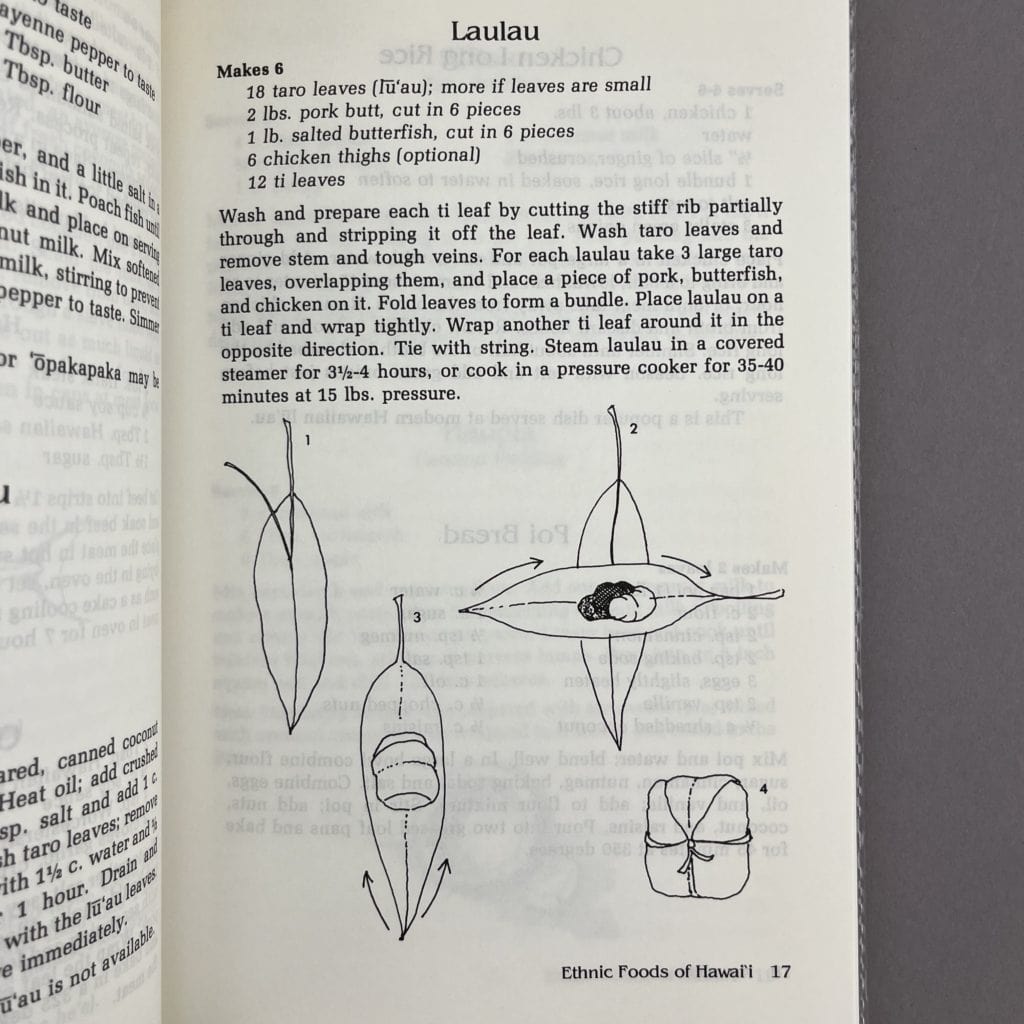

Ethnic Foods of Hawai’i by Ann Kondo Corum

Szathmary Collection TX724.5 .H3 C68 1983

Ann Kondo Corum, formerly a school librarian in Honolulu, wrote and illustrated Ethnic Foods in Hawai’i to provide a sense of history and culture through the foods and cooking traditions of the now multi-racial state of Hawai’i. She saw a need for this during her time as a librarian, when students had trouble finding information about the foods and culinary customs of their peers. This cookbook dives into the history and popular traditional recipes of the major cultural groups on Hawai’i, including traditional Hawaiian and Samoan recipes, celebrations, and culinary customs.

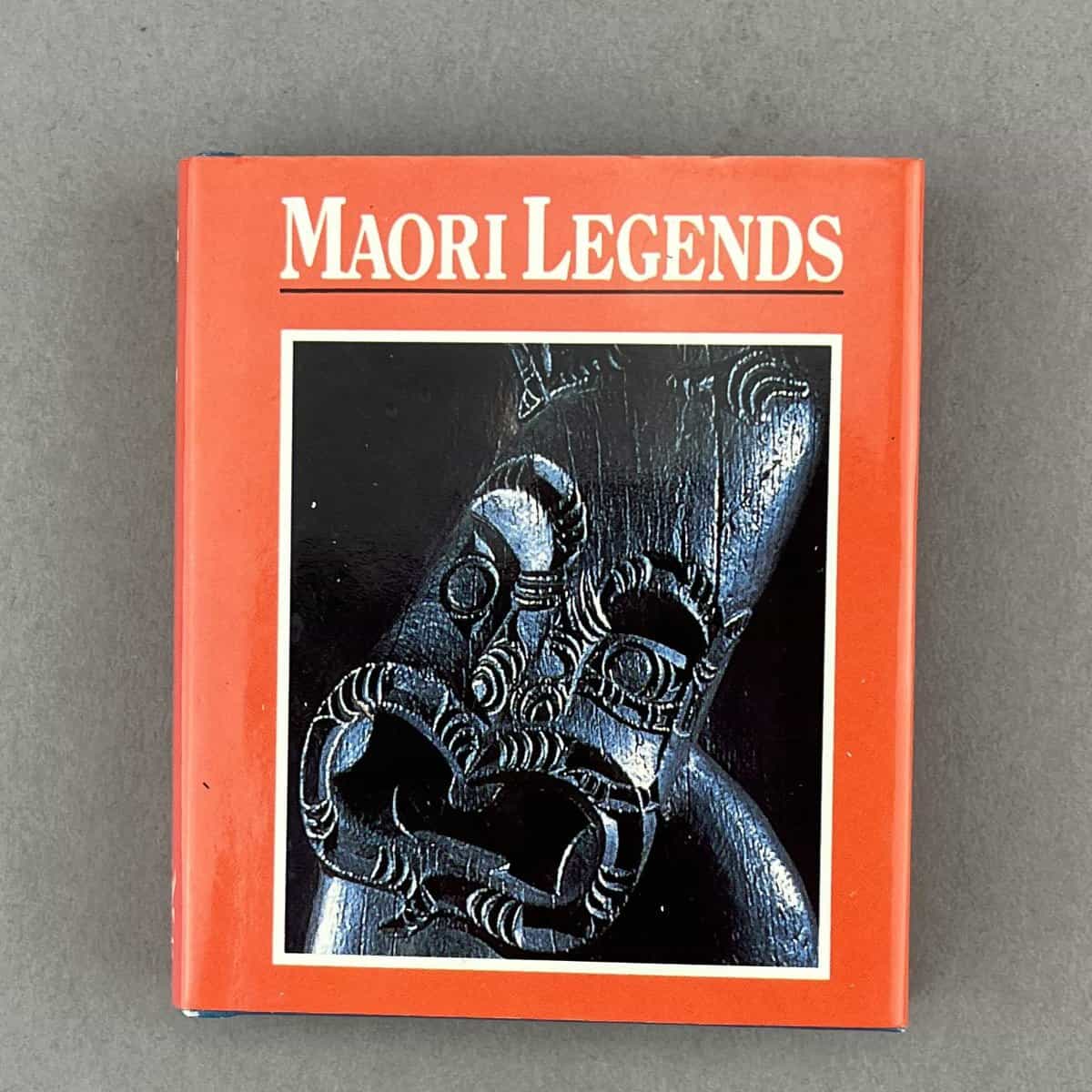

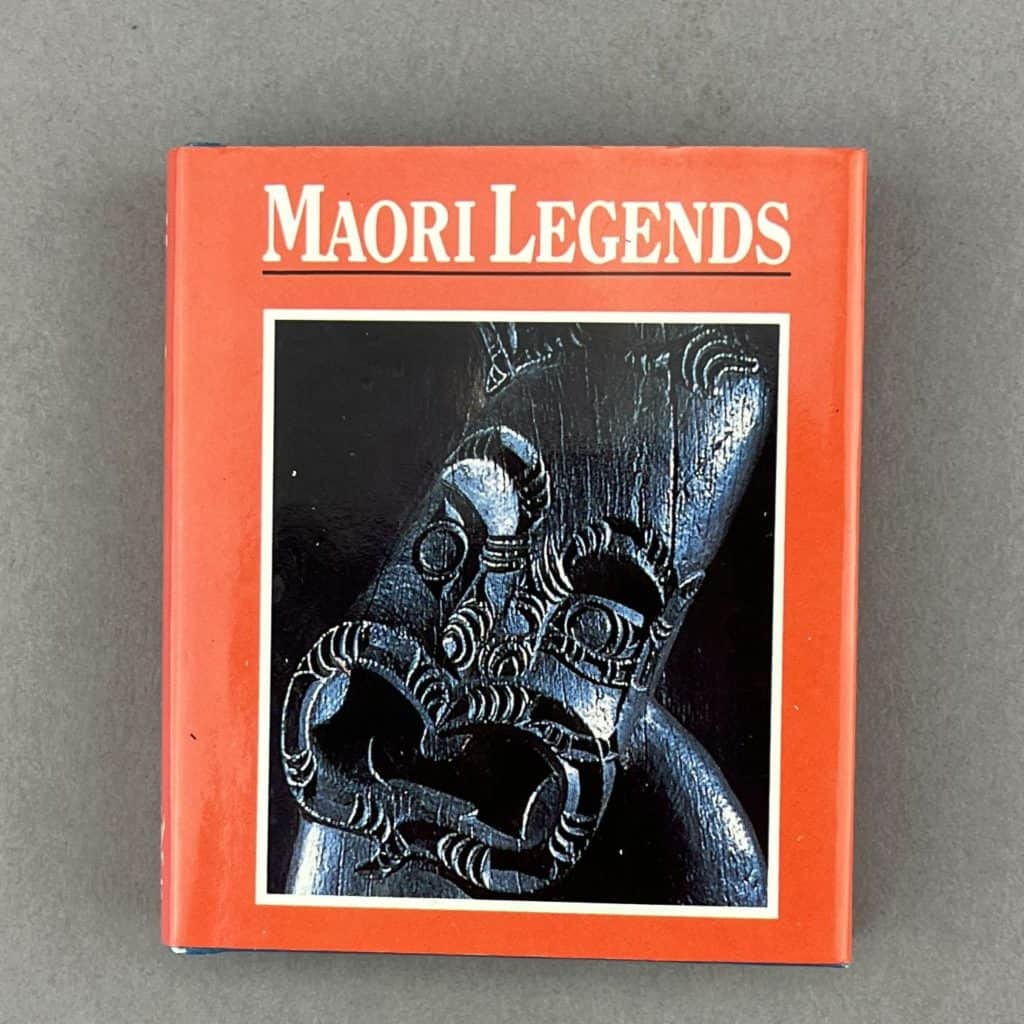

Māori Legends illustrated by Manu Smith.

Smith Miniatures Collection GR375 .M36 1993

This miniature book is the illustrated telling of major Māori legends or oral histories, including those of Maui, Pania, and Rona, the woman who went up to the moon. Illustrations are done by Manu Smith, who is also known for having illustrated Māori legends series for New Zealand stamps and phone cards in the 1980s and early 2000s.

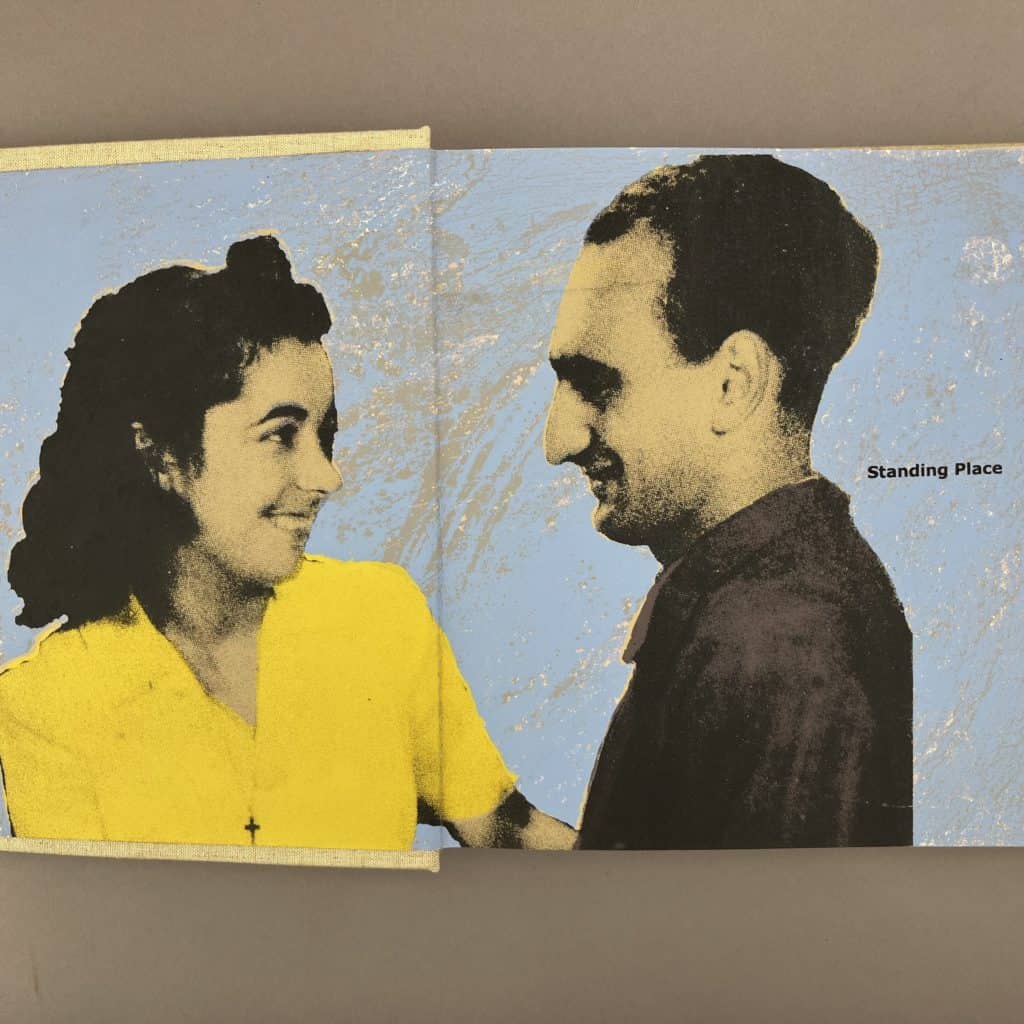

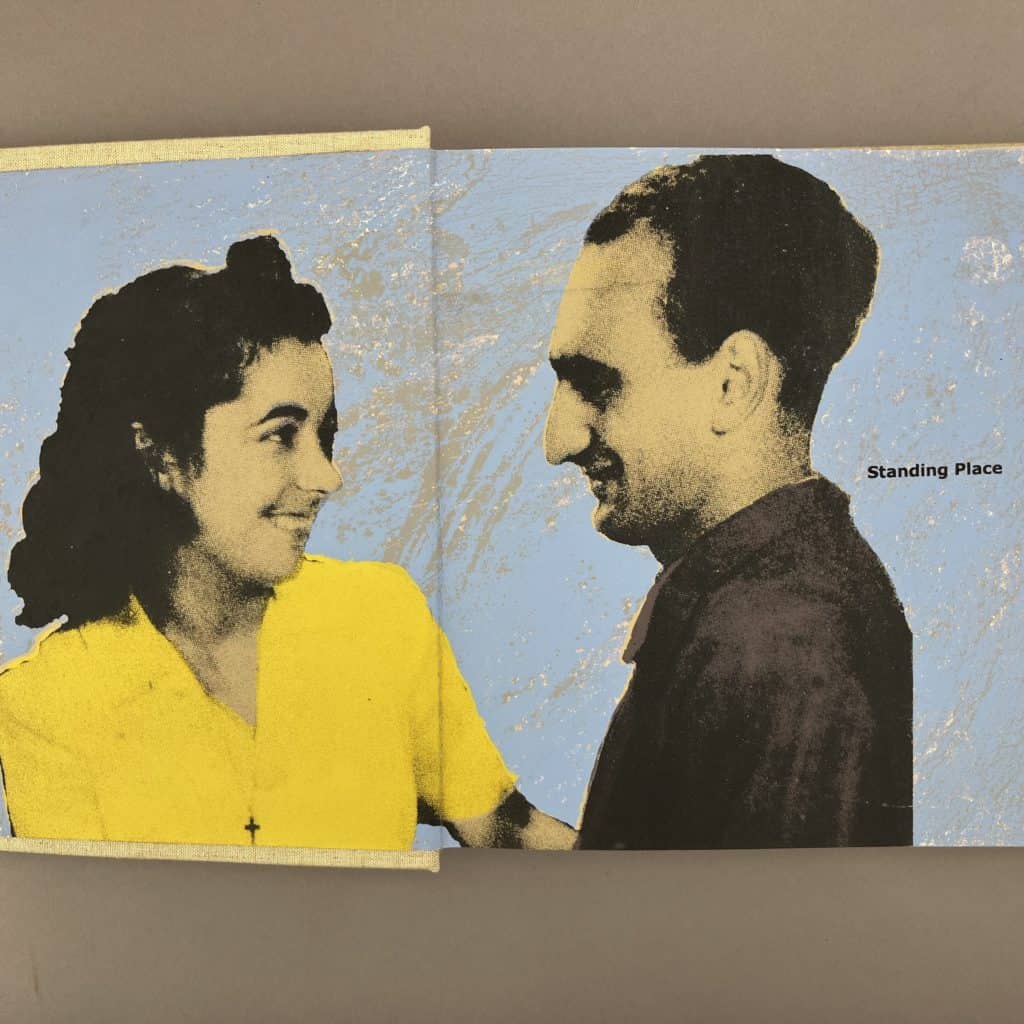

Standing Place by Fred Hagstrom.

X-Collection Oblong N7433.4.H25 S73 2012

Fred Hagstrom is an artist and professor emeritus of art and art history at Carleton College in Minnesota. Standing Place is an artistic telling of a story about shared culture and the soldiers of the Māori Battalion during World War II. This covers the story of Ned and Katina Nathan, who are also the focus of Patricia Grace’s book, Ned and Katina. In his artist statement on the piece, Hagstrom writes: “I take students to New Zealand every two years, and in doing that have made good friends at a Māori Marae, which is a tribal meetinghouse. This is the story of their parents. …They also founded the Marae that I visit. This book is made in the friendship I feel for this remarkable family.” The Marae in mention is the Matatina Marae at Waipoua. The kawai pattern on the book’s cover, titled Tatai Hono (the joining of lines of descent) was designed by Manos Nathan, son of Ned and Katina.

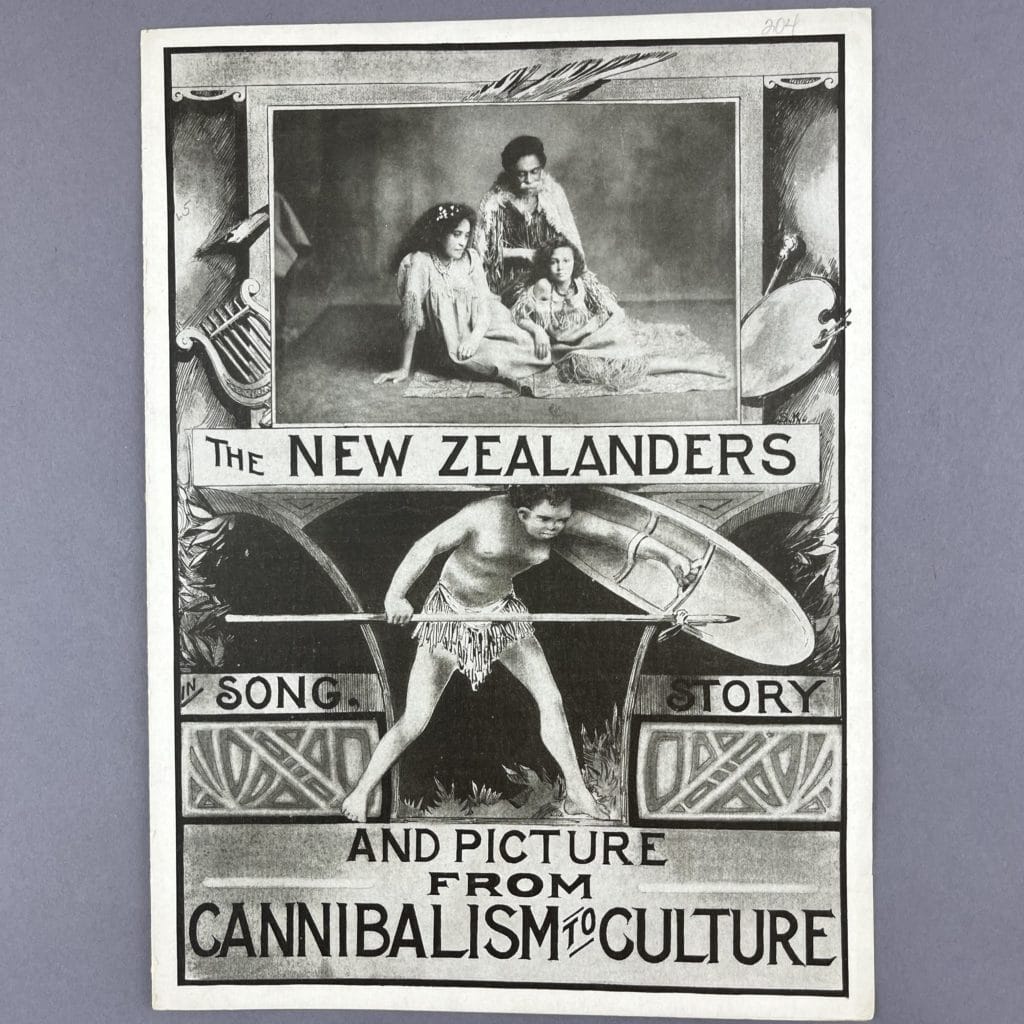

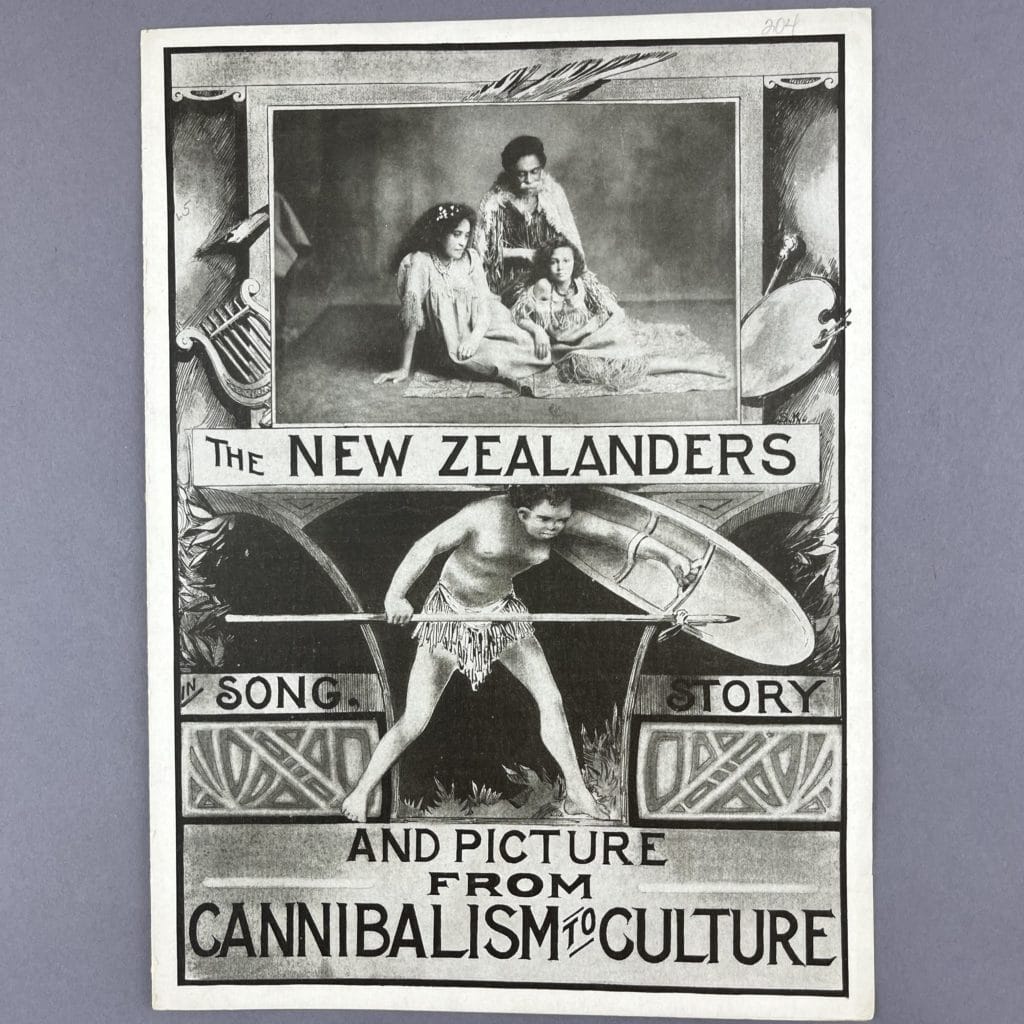

Francis Wherahiko Rawei, from the Redpath Chautauqua Bureau Records

MsC0150 Box 238, Box 272

Francis Rawei, also known by his former name Wherahiko Rawei or his stage name Dr. Rawei, was a Māori performer and educator of the early 20th century. Alongside his wife Hine Taimoa, a lecturer, harpist and singer herself, Rawei toured internationally lecturing, singing and storytelling about Māori history, life, and culture. Together they toured the United States and Canada on the Chautauqua circuit and lived briefly in Chicago before eventually returning to New Zealand.

Also worth mention are the many travel diaries and publications collated by some of the first foreign seamen to arrive in the South Pacific. I have intentionally not included any of these materials, as these diaries are predominantly accounts of travel to these islands with the goal of imperial conquest or religious purification of Indigenous Pacific Islanders, and unfortunately are not without deeply racist and offensive language. This undoubtedly makes these materials challenging to read and engage with, but the effects of colonialism and religious missionary efforts are very real and prominent parts of Pacific Islands history, as well as our present day. Their place in a rare book repository is just as important to the preservation of Pacific Islands history and culture as those included on this list.