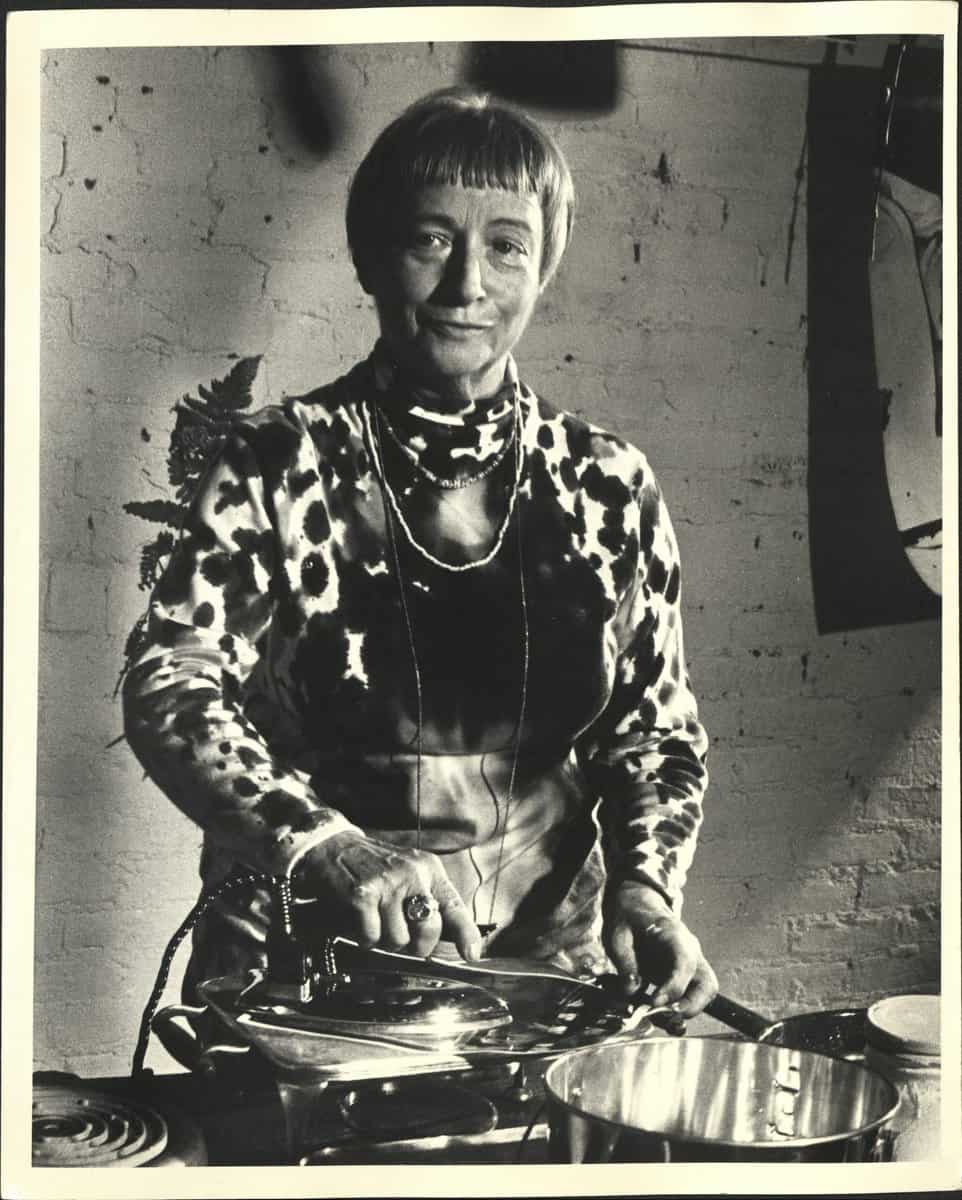

The following is written by academic outreach coordinator Kathryn Reuter. On Tuesday, October 4th, 2022, join the Stanley Museum of Art & the University of Iowa Libraries’ Special Collections and Archives as they celebrate the 123rd birthday of artist Lil Picard! Crafts and cake will be available in the Stanley Museum lobby from 12-2pm, andContinue reading “Happy Birthday Lil Picard!”

Tag Archives: Lil Picard

All Women Welcome: Summer 2022 Reading Room Exhibit

The following is written by Rachel Miller-Haughton, former Olson Graduate Research Assistant and curator of All Women Welcome exhibit All Women Welcome: Voices of Activist Iowa Women is the summer 2022 exhibit in the Special Collections Reading Room. The culmination of my time as the 2020-2022 Olson Graduate Research Assistant, the exhibit features images, documents,Continue reading “All Women Welcome: Summer 2022 Reading Room Exhibit”