The following was written by Olson Graduate Assistant Rich Dana, and curator of the Spirit Duplicators exhibit in Special Collections & Archives reading room

During my three and a half years at Special Collections, I have worked with an amazing range of materials, but my major projects have focused on first, the James L. “Rusty” Hevelin Collection of Science Fiction, and more recently The Ruth and Marvin Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry. As I became more familiar with these and other collections of documents from the realms of both science fiction fandom and the 20th Century Avant-Garde, I began to notice remarkable similarities in the publications of both cultural movements.

I began thinking about a potential exhibit of these zines and chapbooks, and when I sheepishly mentioned this notion to Marvin Sackner in a telephone conversation, he became very excited. “If you could prove a direct connection between fanzines and visual poetry, you would really have something!” He told me that he considered the final pages of Alfred Bester’s 1956 science fiction classic The Stars My Destination to be one of his first experiences with visual poetry.

I set about the task of combing the Sackner Archive and Hevelin Collection for connections. My search expanded to the other areas of the department such as rare books, ATCA Periodicals and Zines Collection, Fluxus West Collection, M. Horvat Science Fiction Fanzines Collection, and many more. A story began to emerge.

Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl, published by City Lights Books in 1956, brought “Beat Poetry” to the attention of the world and helped to spark a new literary movement. But before Lawrence Ferlinghetti published the now-famous Pocket Poets book, there was another edition of Howl printed: a 25 copy run off on a “ditto” machine by Marthe Rexroth in an office at San Francisco State College.

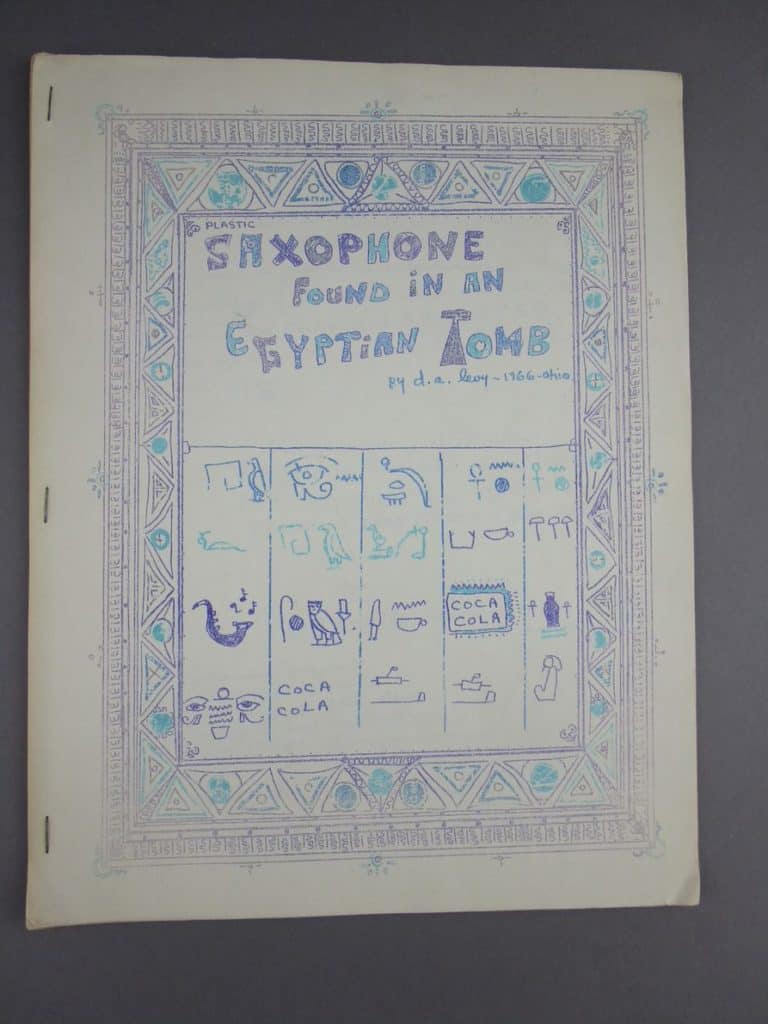

Pre-digital office copiers like the ditto machine (spirit duplicator), mimeograph, hectograph, and tabletop offset press freed 1960’s radical artists and writers from the constraints of the publishing industry and brought the power of the printing press to The People. These writers/publishers of the period, like Leroi Jones (Amiri Baraka), Diane DiPrima, d.a. levy, and Ed Sanders were not the first to use cheap copying technology to produce “democratic multiples,” however.

Blue-collar teenage fans of far-fetched adventure stories had been creating an international network of amateur “fanzines” since well before World War II. From where did the young fans of the fledgling genre of “scientifiction” draw their influences? Undoubtedly, they were imitating the cheaply printed monthly “pulp” magazines with titles like Amazing Stories and Weird Tales. Also, in the zeitgeist of the new industrial age were the seeds of political, cultural, and artistic revolt. Marcel Duchamp arrived in New York along with a wave of immigrants fleeing WWI and the Russian Revolution, which soon also carried the two-year-old Isaac Asimov to Ellis Island. Like a sine wave on a mad scientist’s oscilloscope, the aesthetics of “highbrow” artists and writers and “lowbrow” outsider zine publishers resonated and reflected each other through the 20th Century.

Self-published chapbooks, underground comics, flyers, and fanzines served as proving grounds for many of the 20th century’s most influential creators. However, the “Mimeograph Revolution” remains a little-examined artistic movement, considered by many to be the realm of “lowbrow” or “outsider” amateurs unworthy of serious research. Yet a closer look at the work of many copier artists reveals a high level of technical sophistication and profound social commentary. The works featured in this exhibit introduce viewers to the vibrant American amateur press scene of the early and mid-20th century, and the media that influenced it.

Much like the internet today, duplicators played an essential role in the development of pop culture genres like science fiction, comic books, and rock and roll, as well as avant-garde art movements like Fluxus, pop art, and concrete poetry.

Click here for a video tour of the exhibit through our Summer Seminar Series

Exhibit Highlights

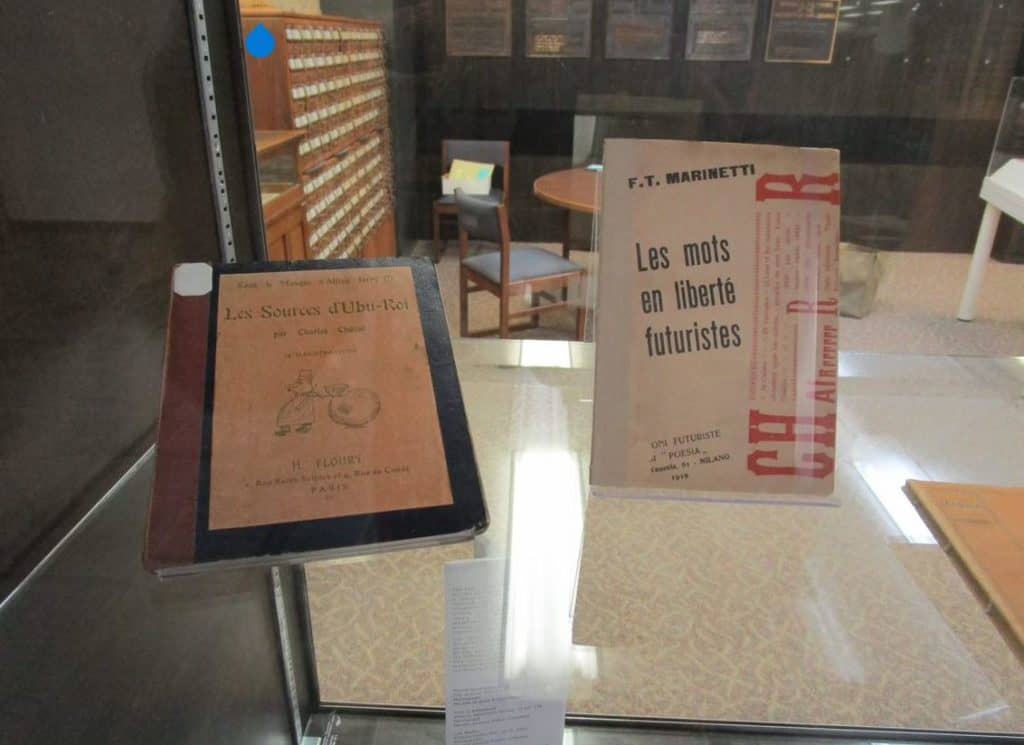

French symbolist Alfred Jarry was the first to influence both the development of science fiction (SF) and the avant- garde. He wrote time-travel stories alongside his friend H.G. Wells and set the stage for Dada with the production of his revolutionary play, Ubu Roi. The turn of the century marked a new obsession with technological development. The newly-built Eifel Tower stood as a monument to the modernist ideal, while Thomas Edison introduced the first mimeograph at the World’s Fair. The Futurist art movement rejected the past in favor of techno-utopianism. Early SF fans like Myrtle Douglas (Morojo) embraced these radical ideas, as reflected in the design of her Esperanto fanzine Guteto (Droplet.) WWII and the rise of technocracy brought much of this idealism to an end.

The avant-garde primarily used duplicators like the hectograph and the mimeograph as a cheap alternative to “better” printing methods like lithography. The true innovators in the use of copiers were an unlikely cohort; science fiction(SF) fandom. Young fans were creating amateur magazines (“fanzines”) imitating the cheaply printed “pulp” magazines like “Amazing Stories” and “Weird Tales.” The fanzines also featured cover art influenced by the graphic style of the avant-garde. For most fans, litho and letterpress printing were out of reach. For them, copiers like home made hecto gelatin pads were the only option. Hectograph and later “ditto” machines produced the distinctive purple copies using aniline dye inks.

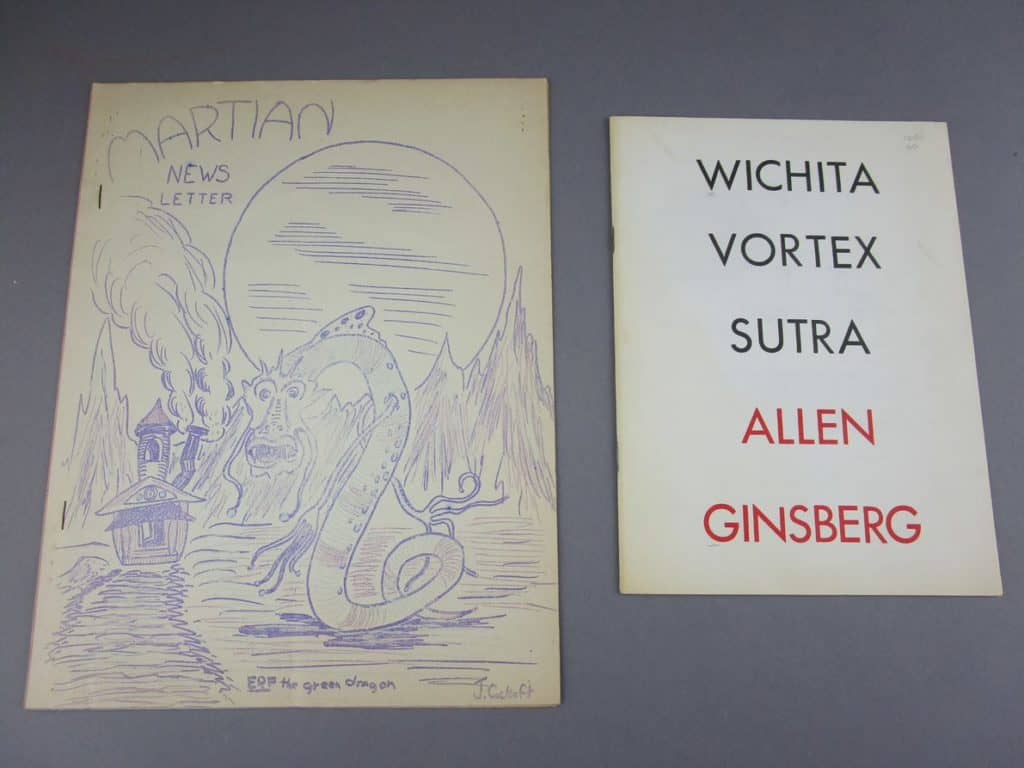

The cross-over between SF fandom, artist books and poetry took place after WWII. Many SF fans returned from the war and attended college, thanks to the G.I. Bill. The university culture of Wichita, Kansas made it a key stop on the cross-country drives of beats like Allen Ginsberg, who titled a poem after a legend he picked up from the Wichita beatniks. The legend of Vortex originated with local beatnik poet (and SF fan) Lee Streiff in the pages of his Mar- tian Newsletter. Unlike other Wichita beat poets and artists, Lee Streiff never escaped the Wichita Vortex, where he taught English and continued to participate in fandom.

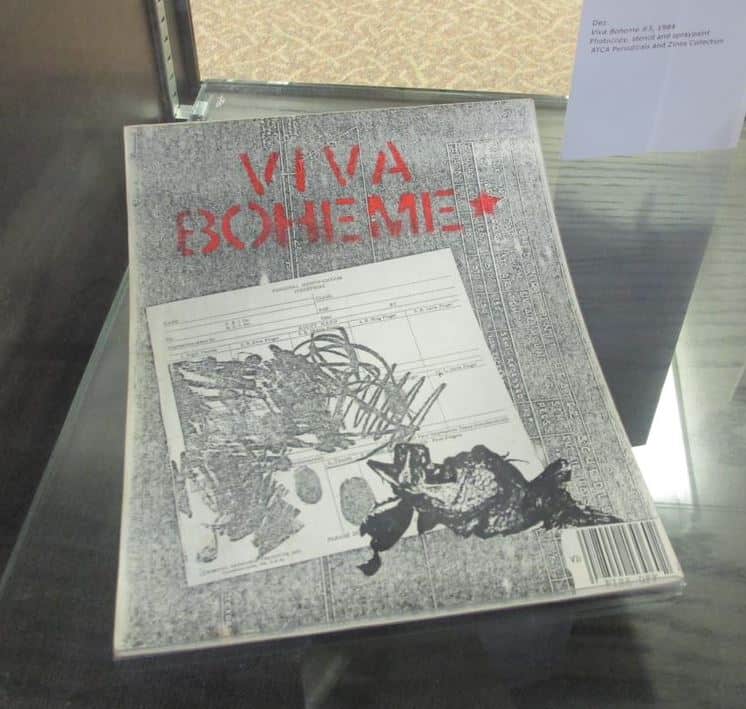

Every social justice movement of the 20th century relied on cheap copying technology, coupled with bold (and often crude) graphics to spread their message. Spirit duplicators, often called ditto machines, used a paper master sheet similar to carbon paper to print up to 40 purple or green copies before the master was depleted. The mimeograph, or stencil duplicator, also used a paper master sheet, but allowed the user to make more copies in a wide range of colors. The offset press, used to produce larger runs, is an offshoot of lithography and uses a flexible printing plate. This process is still used on a large scale for newspaper.