This post by IWA Student Specialist, Erik Henderson, is the sixth installment in our series highlighting African American history in the Iowa Women’s Archives collections. The series ran weekly during Black History Month, and will continue monthly for the remainder of 2020.

Has anyone told you, you were going to be great in your youth? Have you been pushed to excel beyond levels you could imagine? Has there been something you wanted to fight for that became a lifelong journey? In her oral history interview from October 1986, Esther J. Walls, former librarian, administrator and educator, illustrates a few of her life goals and approaches used in accomplishing them. While exploring Walls’s papers, one embarks on a journey with her to change the perception of Black and brown adults and youth, through literacy and programming. On the path to legacy, what distinguished Walls’s journey from others was her distinctive childhood in Mason City, Iowa, her ability to connect with young people of color in New York, and her overall international presence. In the midst of global protest about the murder of George Floyd, the role of a Black leader is critical for change. Looking at the life of Esther Walls, we can look at her actions, her persistence, and her willingness to not give up as key attributes for a Black leader during movements like this.

The interview begins with Esther Walls introducing herself and answering the question how she got involved with the Black experience. Walls answers with examining her childhood. She says, “as a youngster in Mason City, Iowa, I do remember my mother and my sister and myself frequently going to the library and coming home with the equivalent of a shopping cart full of books.” Those growing up in communities that do not reflect them must obtain positive images, outside of family, through books, music, movies, etc. For Walls, she found an escape through reading literature by Black authors. “Living in Mason City, Iowa, where there weren’t very many Blacks, meant anything that we could read about the Black experience was something that was terribly important to us.” Her love for books began at a young age but her drive to excel scholastically took off in the seventh grade. Walls stated in the interview that she was determined to be valedictorian of her class, and she completed that mission.

Walls attended Mason City Junior College before transferring to the State University of Iowa (University of Iowa), where she received her B.A. in 1948. She was the first Black woman at the University to be elected to the Alpha of Iowa Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, the oldest and most prestigious undergraduate honors organization in the United States. However, Walls was most known for being one of five Black women to officially desegregate university dormitories.

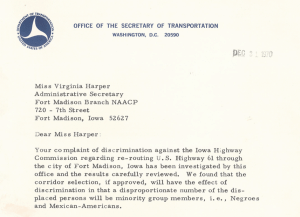

In 1946, during an era plagued by the Jim Crow laws, Esther Walls, Virginia Harper, Leanna Howard, Gwen Davis and Nancy Henry, all Black women, protested against the segregated housing at the University of Iowa. “It seemed to be something so normal that should’ve happened. I had a right to be in Currier Hall. Why not?” Walls shared. “I was the valedictorian of my high school class, and I was from the state of Iowa.” Ironically, Walls was excluded from and had to fight to live in a building that was named after a university librarian, yet, she became a librarian herself that did remarkable things for her community and people. None of the women allowed the values and “norms” of the time to deter her from achieving greatness.

After Walls and the other four women succeeded in desegrating housing at UI, years later another instance of discrimination arose. Martha Scales-Zachary and Betty Jean Furgerson, Black women living in Currier Hall, had to switch residences when students’ parents objected to desegregated living quarters. During that same school year, a policy was implemented where no out-of-state student could reside in Currier, only Iowa residents, which applied to Black women and not Black men. Sadly, there is not any information we could find regarding how Black men made an effort to get to live on campus but we will continue digging to uncover hidden stories.

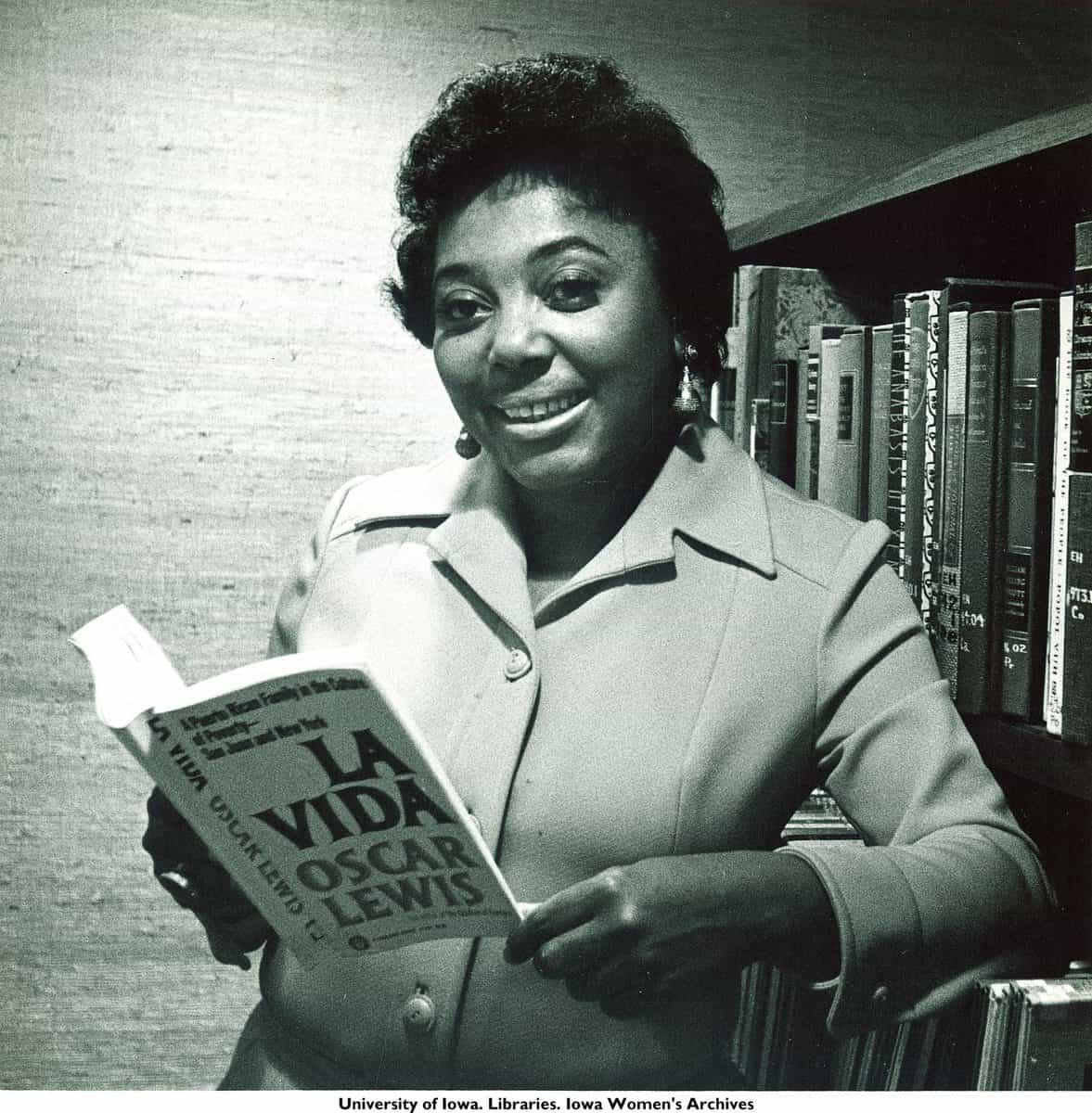

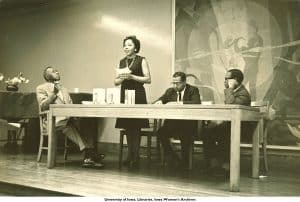

After graduation, Esther Walls obtained employment at the Mason City Public Library then headed to attend Columbia University, receiving an M.S. in Library Science in 1951. Walls began working for the New York Public Library in 1950, carrying out various professional assignments: including serving as director of the North Manhattan Library Project and as head of the Countee Cullen Regional Library. Her reign at the Countee Cullen Library, “was the thing that really opened up all kinds of horizons for me and made me understand in depth, what the Black experience was all about,” she describes.

In a speech for the New York College Department of Library Education-Geneseo, about her work with youth, Walls explains how her focus on interactions with teens, and her open approach, made a lasting impact on them. Walls was persistent about leaving a positive influence on the patrons she served, and challenged the community as well. In her speech, “Experiences as a Young Adult Librarian,” Walls reflects on her earliest lessons learned as a librarian, one being: one has to be knowledgeable in all aspects of their job. She was not only knowledgeable of her library plus the Schomburg Collection that was connected but also of what her patrons valued, cared about, and needed to succeed and thrive in their neighborhoods. She was able to stimulate the Harlem community by bringing people such as Malcolm X in for weekly lectures, Langston Hughes to do poetry reading and Michael Olatunji to come and play his drums for teen programs. Within the interview she expresses her compassion for meeting these prominent figures in the restaurants of Harlem during the 1960’s:

“What intrigued me no end was meeting all these people that I, either meeting and getting to know some of these outstanding Blacks in the community at that time….So then for me it was an opportunity to meet all of these people, if not to get to know well, at least to be in the presence of all these people that we had read about in the newspapers and who were really making waves and making headlines, and I found that quite exciting.”

Walls believed that the best way to be connected to those she served, was to recommend books that they would enjoy. Accomplishing this task took getting to know her patrons, spending time asking them questions to fully understand their position in, and perspective on, the world. Additionally, this meant reading materials young adults gravitated towards. Walls attests that she “read as many books on dating, hotrods (cars) and space travel, as she could.” This is a speech that provides the audience with qualities and tools to be successful when working with young adults.

With few other Black people in Mason City, besides her skin color, Walls did not have anything that identified herself as part of the Black community. It was not until an interaction with a library patron at one of her first programs that said, “are you Esther Walls? We’re so glad and we’re so glad you’re Black.” Although, only mentioning it briefly, Walls’ discussion of her situation moved me. Myself, being a Black man from Chicago, a city with a large Black population, hearing that sentiment touched my heart. Black people living in small, rural parts of America, do not experience life the same way that as ones from the intercity and vice versa. However, a medium such as books connects those people from different backgrounds because, even though we are not walking down the same path, we are walking in the same shoes. Learning about Esther Walls’s legacy, opens up dialogues about the importance of having your own identity and community. Developing a sense of identity, whether through literature, art or cinema, no matter where you reside geographically is crucial for connecting with those that look like you.

The Esther J. Walls papers are one of the few collections that is fully digitized onto the Iowa Digital Library (IDL). You are able to explore everything that you could see in our reading room! A useful tool to have open when diving into Esther Walls’ material on IDL, is her finding aid, which you can also find online, on ArchiveSpace at the University of Iowa.

Citations

Esther J. Walls interview, October, 1986 https://digital.lib.uiowa.edu/islandora/object/ui%3Aaawiowa_3991

Esther J. Walls papers, Iowa Women’s Archives, The University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City. http://aspace.lib.uiowa.edu/repositories/4/resources/2406

Franklin, V. P., & Savage, C. J. (2004). Maintaining a Home for Girls. In Cultural capital and black education African American communities and the funding of black schooling, 1865 to the present (p. 133). Greenwich, CT: IAP, Information Age publication

Jensen, C. (2015, October 19). Iowawomensarchives: EstherWalls-librarian and… Retrieved May 22, 2020, from https://womenoflibraryhistory.tumblr.com/post/131488735229/iowawomensarchives-estherwallslibrarian-and