“Gentlemen,

As you had hoped, I have found your questionnaire interesting to answer. However, I cannot refrain from expressing my resentment at the phrasing of certain statements, which seem to me to reflect discrimination on the basis of sex.”

So begins Dr. Dorothy Wirtz’s 1969 letter to The Carnegie Commission on Higher Education. She followed her opening statement by citing precisely when the Commission assumed that the professors they surveyed would be men. She told them, quite directly, that “Women are people, too, and even manage to exist in the profession.” By 1969, Wirtz knew about existing in “the profession” as a woman, and had been a professor of French at Arizona State University for 10 years.

Dorothy Wirtz had been an outstanding student with a talent for writing and linguistics. While still an undergraduate at Culver-Stockton College, she won the Vachel Lindsay prize in poetry. After transferring to the University of Iowa, her letters home displayed focus and diligence concerning her studies in French and German. She packed her bags for the University of Wisconsin almost immediately upon graduation. There, after writing a dissertation on Flaubert, she received both a Master’s and a PhD in French by 1944.

The path from school girl in Keokuk, Iowa to doctoral candidate in Madison, Wisconsin was exceedingly unusual for a woman in the 1940s. According to a National Science Foundation report from 2006, women received only 27% of doctorate degrees from 1920 – 1999, and 43% of those were issued in the 1990s. As an aspiring professor of French in a field dominated by men, Wirtz must have known she did not exactly meet prospective employers’ expectations.

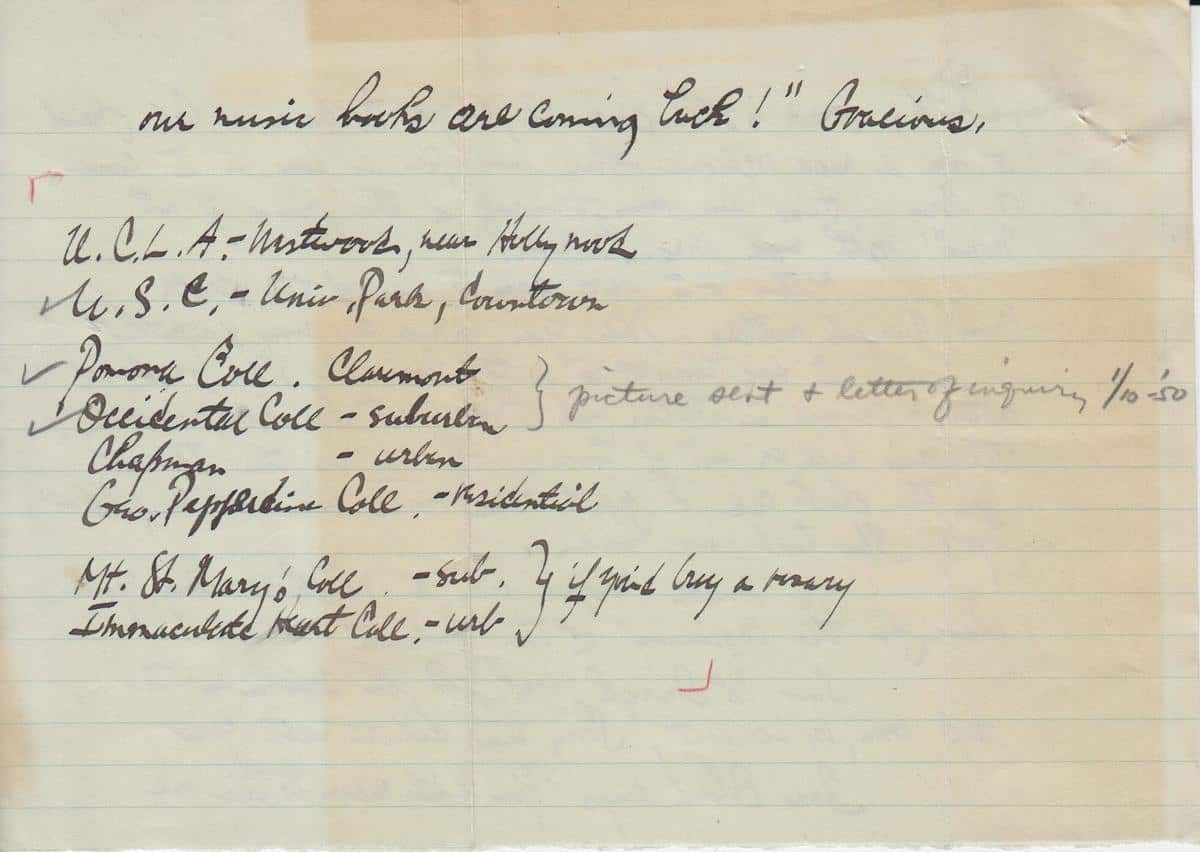

This fact was made clear when, after a few years at the University of Minnesota, she tried to join her parents and brother in Arizona. In 1950, Wirtz’s brother, Warren, sent her a list of colleges where she could apply including two Catholic institutions, jokingly adding “if you’d buy a rosary.” Dorothy noted her progress on the job search in pencil with check marks, but had no luck. A friend of Warren’s made inquiries on Dorothy’s behalf but confessed in a letter “The trouble was simply (with some question about ‘research’) that there was not a position open in the upper brackets to a woman. I doubt very much that they would appoint a woman assistant professor in our department. She probably knows this.” He went on to suggest that she try “various junior colleges” in Los Angeles. The job market wasn’t just tight. It was practically impassable.

Without a job offer and only vague plans to teach, Dorothy Wirtz moved to Arizona. For several years she worked outside of academia, eventually serving as the Deputy State Treasurer of Arizona. But the tenacious Wirtz never gave up and in 1959, she secured a position at Arizona State University. She was four years from retirement when the Carnegie Commission sent her their biased survey. Although she did not shy away from making a political point in her letter, true to her field of study, she ended her letter by suggesting that the impersonal pronoun would have been the best choice linguistically and wished them well in their survey.

Thurgood, Lori, Golladay, Mary J., and Hill, Susan T. “U.S. Doctorates in the 20th Century.” National Science Foundation Special Report (2006). http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf06319/pdf/nsf06319.pdf.