The following is written by M Clark, instruction and reference graduate assistant of Special Collections and Archives

In the blossoming world of the international Art Nouveau movement of the late 1800s, German artists were carving their own unique path that reverberated across Europe. At the heart of this movement stood publications such as PAN, a Berlin-based art magazine that epitomized the era’s youthful spirit and desire to overcome historicism and the endless copying of other art styles. From its inception in 1895 to its culmination in 1915, PAN’s journey mirrored the evolution of German Art Nouveau, capturing the essence of a fleeting yet transformative period in art history.

The international Art Nouveau movement, coming from the French meaning “new art,” began in western Europe as a reaction against academicism, historicism, and neo-classism of the 19th century. A refusal of the official art and architecture academies and their teachings led to a movement with the goal to make art that would not only belong in the museum, but art for the people. Art Nouveau took inspiration from the British Aestheticism movement of the same time period, and its underlying focus on the production of ‘art for art’s sake’. The art, architecture, and applied or decorative art styles birthed by Art Nouveau were often inspired by natural forms and movement, the earlier years of the movement being inspired by the British Modern Style and Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, and the later years being inspired by Secessionism, Abstraction, and the combination of floral decoration with geometric forms.

Across Europe, distinct regional sects of Art Nouveau emerged, each reflecting nuanced variations in artistic expression and cultural influences. Germany, in the center of Europe, saw its own unique impacts and shifts brought by regional aesthetics. The German counterpart to Art Nouveau came to be called Jugendstil, translating to “the style of Jugend,” or “youth style”, ultimately being named after the Munich Secession art publication, Jugend. It’s symbol was the swan, inspired by the creature’s prevalence in Japanese art. August Endell, an eventual editor of PAN and major Jugendstil decorative arts figure is quoted having said on behalf of Jugendstil artists, “we are on the threshold of not only a new style, but also the new development of a completely new art; the art of applying forms of nothing insignificant, not representing anything, and not resembling anything.” Jugendstil is claimed to have been launched by the sculptor Hermann Obstrist in Munich in the 1890s, whose art was motivated by visions of architecture and design ‘in motion’.

The birth of Jugendstil is attributed to four different major cities in Germany – Munich, Berlin, Karlsruhe, Dresden – each having contributed uniquely to the whole of the German Art Nouveau movement. From the art and artists of these cities came key art publications such as Jugend and Simpiclissmus out of Munich, and PAN out of Berlin. The goal of these magazines was to make accessible new art, creative writing and cultural commentary to the newly literature public of the late 19th century. These magazines, as vessels of the larger art movement, rejuvenated people’s interest in art and design.

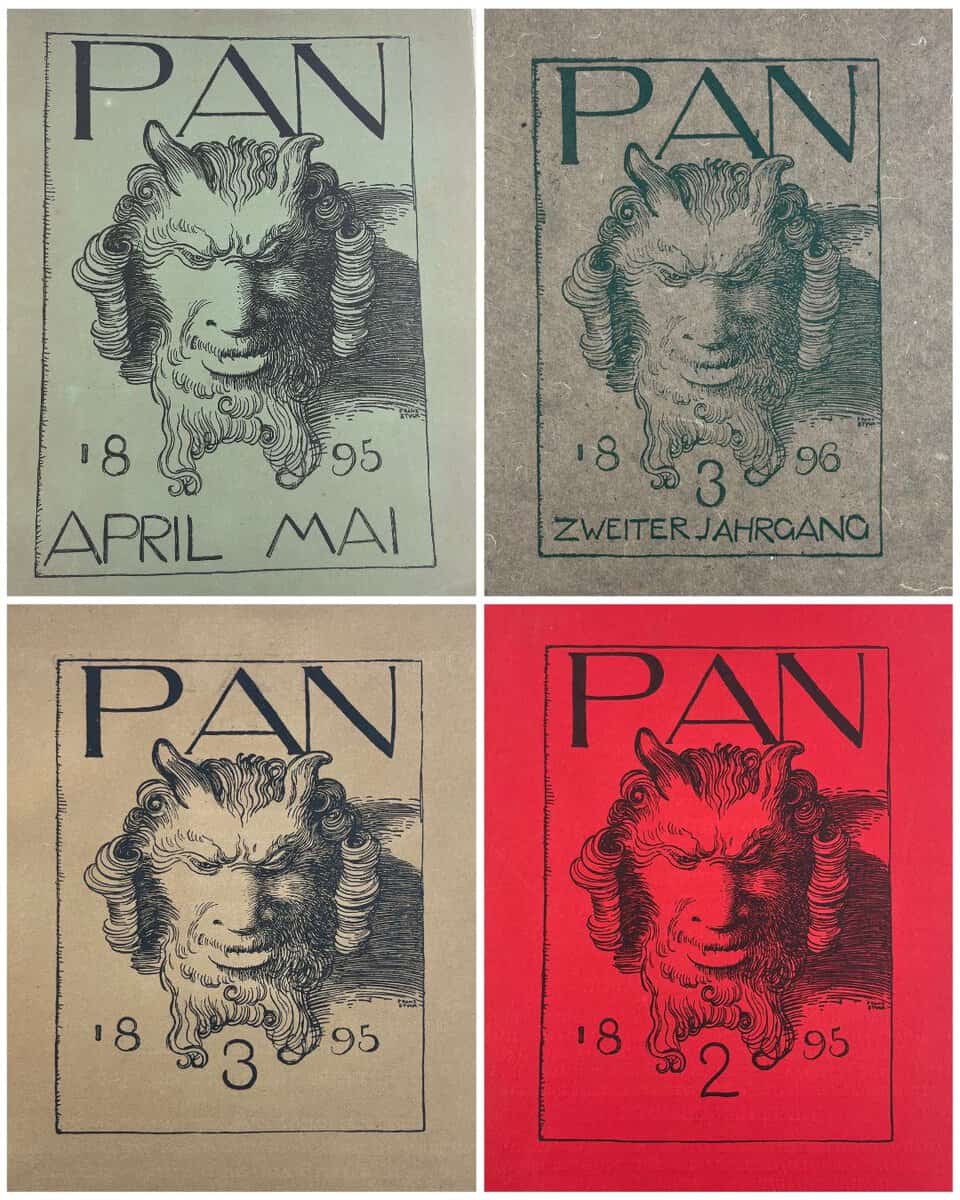

Founded by Richard Dehmel, Otto Julius Bierbaum, and Julius Meier-Graefe in Berlin in 1895, PAN was more than just an arts publication. With its name drawn from the Greek god associated with fertility and creativity, and the Greek word meaning “all”, PAN symbolized an emergent vision of artistry that was being led and shaped by a collective. Published in Berlin at the height of Art Nouveau by the artists, writers, and designers of the PAN Co-operative made themselves unique from other German artist publications through its frivolous and decadent production. PAN was the most expensive artistic magazine of its time, with its standard monthly subscription costing 75 Reichsmarks, or RM (308 USD in 2024). Compare this to Jugend’s monthly 24 RM (123 USD in 2024). Subscriptions to PAN were offered in three tiers: standard, printed via copper plate on what was likely wood pulp paper; luxury, printed onto imperial handmade paper; and the artist’s edition, which were luxury edition magazines that included additional original art on various expensive papers, which were only available for purchase to members of the PAN Co-operative for 300 RM (3,116 USD in 2024).

This tiered system, as well as the emphasis on returning attention to the artist collective that made the magazine possible, gave PAN its reputation as one of the most exclusive periodicals ever published in Germany. In contradiction to these high costs and marketing towards an elite clientele, PAN’s publishers claimed to be disinterested in financial gain, and instead intended the goal of the magazine to uplift young artists. Artists who grew noteworthy through their participation include Franz Stuck, Peter Behrens, Otto Eckman, and many others. The magazine sought to show the best of the best in terms of contemporary art, architecture, writing, and social commentary, showing no preference to any particular school or movement of art. Most notably this included pan-European expressionist and naturalist art, and stories and poems from western Europe, predominantly Germany, France, and England.

However, PAN’s lack of a clearly defined style and breadth of published mediums can be attributed to the magazine’s eventual downfall, alongside its high turnover of editorial leadership. Since its first volume in 1895, the editors of PAN struggled with establishing consistency in both the content and release of published issues. The magazine’s first volume included five issues published monthly, which would be changed to four issues published quarterly for the magazine’s remaining volumes. The earliest issues of PAN show the changing trajectory in the choice of paper, cover art, and balance between art and writing. Later issues reveal attempts to highlight singular artists at a time and the inclusion of a routine “Rundschau”, or review.

This inability to establish a clear direction for the future trajectory of the magazine was intensified by its unique phases under different editors. By 1900, production of PAN had stopped, and artists began emphasizing simplistic design. In 1910, the magazine experienced a brief resurrection with German art dealer Paul Cassirer stepping in as editor. Cassirer, a leading promoter of the Berlin Secession and Impressionist art movements, revived PAN in an effort to bring heightened attention to Berlin Secession art and writing and the criticism of restrictions imposed on German artists by Kaiser Wilhelm II. The magazine would stop being published in 1915.

Despite its short but intense history, PAN magazine culminated to five volumes, totaling 21 issues and 225 published artistic supplements, original or otherwise. Between the three different tiers of quality available, likely 1200-1600 copies of each issue were published, the fewest of course being the artist’s editions. Rare as they have become, the University of Iowa Special Collections and Archives is the proud host of a near complete collection of artist-edition PAN magazines that are available for patron use. Discover which ones we have in our catalog and come view them in our reading room here at the Main Library.

Sources:

“Art Nouveau.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 24 Apr. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_Nouveau. Accessed 20 May 2024.

“Jugendstil.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 18 May 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jugendstil. Accessed 20 May 2024. PAN – Digitized, www.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/Englisch/helios/fachinfo/www/kunst/digilit/artjournals/pan.html. Accessed 20 May 2024.

“Pan (Magazine).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 8 Apr. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pan_(magazine). Accessed 20 May 2024.

“PAN in an International Perspective.” PAN in an International Perspective | Driehaus Museum, driehausmuseum.org/blog/view/pan-in-an-international-perspective. Accessed 20 May 2024.

Washington County Museum of Fine Arts, wcmfa.org/from-the-pages-of-pan-art-nouveau-prints-1895%E2%80%921900/. Accessed 20 May 2024.