The Hardin Library will be closed for all home Iowa football games. The 24-hour study will be available to University of Iowa affiliates with an Iowa OneCard or UIHC badge.

Closed:

- Aug. 30

- Sept.13

- Sept. 27

- Oct. 18

- Oct. 25

- Nov. 15

- Nov. 22

The University of Iowa Libraries offers a range of mobile apps for clinical care affiliates at no cost. See the full list here.

If you need help getting started with mobile resources, request a workshop in Mobile Resources or contact your specialist librarian.

EndNote 2025 is now available for University of Iowa faculty, staff, graduate and professional students, residents, and fellows. Below, you can see the new features that we think are relevant to your work and research.

Find more information about these key features from Clarivate. Clarivate also provides online training. The UI Libraries also offers a research guide with EndNote and other citation tools. If you need help getting started with EndNote, or would like help with advanced features, please contact your librarian. We’re here to help you succeed!

It’s July and time for a beloved week in television: Shark Week. These sleek, weird, and beautiful apex predators are mesmerizing and also a little terrifying. But what do sharks have to do with medicine?

Surprisingly, quite a bit—thanks to Elementorum myologiae specimen [A Sample of the Elements of Myology] (1667), a work by 17th-century Danish physician, geologist, and Catholic bishop Niels Steensen (Latinized as Nicolaus Steno). His life and work gave us the anatomical-geological mashup we didn’t know we needed.

Born in Copenhagen in 1638, Steensen’s early life was marked by fragility and curiosity. Surviving a mysterious illness of his own at age three, he grew up during a time of plague. The 1654–1655 outbreak claimed 240 of his schoolmates, a tragedy that likely shaped his deep interest in the natural world.

Educated in the classical sciences, Steensen wasn’t one to accept inherited wisdom. By 1659, he was already challenging long-held beliefs, questioning everything from the origin of tears to the nature of fossils.

Steensen began his medical studies at the University of Copenhagen. Encouraged by his anatomy professor Thomas Bartholin, he set off across Europe to study with the best minds of the time. His journey took him from Rostock to Amsterdam, Leiden, France, and finally Italy.

In Amsterdam he studied under Gerhard Blasius. There, he made his first major discovery: the parotid salivary duct, now known as the Stensen duct. His meticulous dissections of animal heads revealed previously unknown structures, culminating in his 1662 publication Observationes anatomicae, which redefined the anatomy of the salivary glands.

His anatomical work didn’t stop there. While studying cow hearts, Steensen came to a radical conclusion: the heart, long thought to be the seat of the soul and source of innate heat, was simply a muscle. In De musculis et glandulis (1664), building on William Harvey’s De motu cordis (1628), he boldly declared, “The heart…is nothing more than muscle,” challenging centuries of Galenic and Aristotelian doctrine.

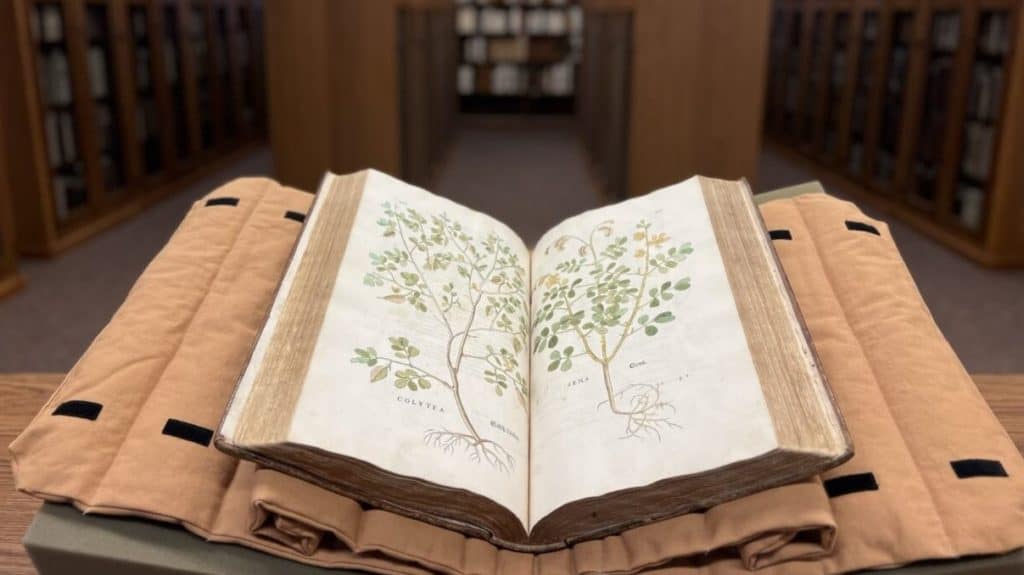

It was in Italy in 1666 that Steensen had a fateful encounter with a shark. This moment would deepen his anatomical studies and spark a new scientific passion that helped lay the foundations of modern geology.

A massive shark was caught near Livorno, and its head was sent to Steensen by order of Grand Duke Ferdinando II de’ Medici. During the dissection, Steensen noticed something striking: the shark’s teeth looked exactly like “tongue-stones”—fossilized objects found far inland, long believed to be petrified dragon tongues. This observation sparked a new obsession: geology.

Steensen’s genius lay in his ability to connect disciplines. His insight—that fossils were once-living organisms embedded in rock—led to foundational principles in geology. In De solido intra solidum naturaliter contento (1669), he laid out ideas that remain central to the field today, including the law of superposition and the concept that Earth’s layers tell a readable history.

Despite his scientific achievements, Steensen’s life took a spiritual turn. In 1675, he became a Catholic priest and later a bishop. He served in various cities across northern Germany, embracing a life of poverty and religious devotion. He died in Schwerin in 1686 at just 48 years old. In 1953, during a canonization process, his remains were exhumed, though his cranium was mysteriously missing. In 1998, Pope John Paul II beatified him, honoring both his piety and his scientific legacy.

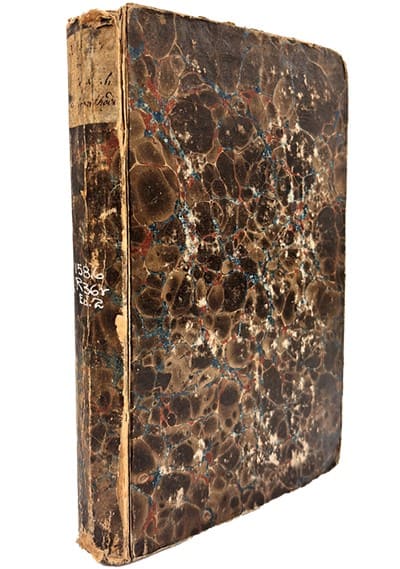

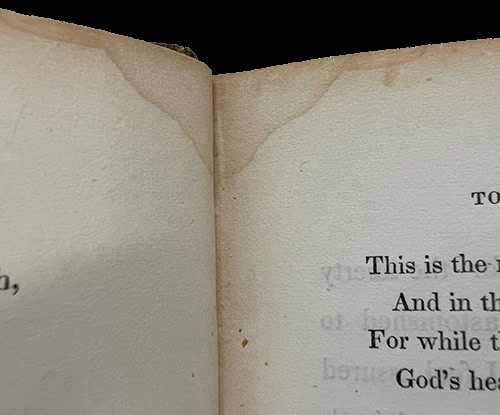

Our copy of Elementorum myologiae specimen is bound in limp vellum over paper boards. The cover has contracted over time, giving it a pronounced bow. The text block is made of sturdy paper with minimal foxing or staining. A few sections remain unopened at the top, untouched since the 17th century. And the smell? A sweet, cheesy aroma that might sound off-putting, but is oddly pleasant.

∼FIN∼

TENO, NICOLAUS (1638-1686). Elementorum myologiae specimen. Printed in Florence by “the printing house under the sign of the Star“, 1667. 25 cm tall.

Contact the John Martin Rare Book Room curator, Damien Ihrig, to see this book at damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154.

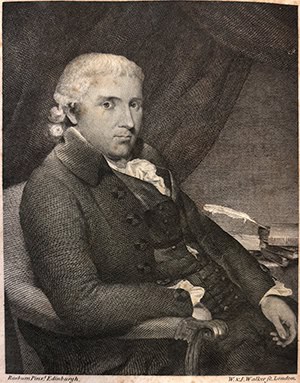

Benjamin Bell (1749–1806), a pioneering Scottish surgeon and father of the Edinburgh school of surgery, authored A Treatise on the Hydrocele, on Sarcocele, or Cancer, and Other Diseases of the Testes (1791). Known for his rational, scientific approach to surgery, Bell also wrote the influential A System of Surgery (1783–1788). He was closely connected with leading medical minds of his time, including Alexander Monro secundus, John Hunter, and Percivall Pott.

Born in Dumfries, Scotland, Bell was the eldest of 15 children. Thanks to his father’s modest wealth, he studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh under renowned teachers like Monro, Joseph Black, and John Hope. He later expanded his training in London and Paris, where he was inspired by Joseph Priestley’s scientific lecture at the Royal Society.

Bell’s surgical innovations included his “save skin” principle, which improved healing in procedures like mastectomies and amputations. He also championed the use of opium for post-operative pain relief—an early advocate for patient comfort.

His legacy extended beyond his writings. His great-grandson, Joseph Bell, became a legendary diagnostician whose keen observational skills inspired Arthur Conan Doyle’s creation of Sherlock Holmes.

Bell’s 1791 A Treatise… was written in response to requests for more detail on testicular diseases, a topic he had briefly covered in his earlier work. The book explores the anatomy, pathology, and surgical treatment of testicular conditions, including hydrocele and cancer. Though it lacks procedural illustrations—a common critique—it reflects Bell’s deep engagement with contemporary medical research across Britain, Europe, and America. Written in a clear, accessible style, it includes numerous references to other studies and cases.

Appropriately enough, we have two copies of A Treatise…, both providing a peek into book production at this time. The first has its original paper covers with many of the textblock sections unopened. Although originally covered in brown leather over paper boards, the other copy is in much worse shape. The leather has been removed from a substantial portion of the covers, the spine is almost entirely missing, and the front board has detached. Our Conservation and Collections Care team has stabilized both books with boxes, though, so we should be able to keep using them for centuries to come.

BELL, BENJAMIN (1749–1806). A treatise on the hydrocele, on sarcocele, or cancer, and other diseases of the testes. Printed in Edinburgh by Bell & Bradfute etc., 1794. Two copies: 23 and 22 cm tall.

Contact the John Martin Rare Book Room Curator Damien Ihrig at damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154 to see these books in person or virtually.

This month, we highlight a book from the early 19th-century French physician who created the most iconic symbol of healthcare providers around the world. Assessing the condition of a patient in 1816, René Laënnec (1781–1826), rolled up a piece of paper to create a crude cone and proceeded to listen to the patient’s chest sounds. Thus was born the stethoscope (from the Greek, stethos:chest and skopé:examination).

Along with the stethoscope, he advanced the understanding of peritonitis and coined the term “cirrhosis” to describe the liver’s tawny appearance. He was the first to lecture on melanoma, describing its spread to the lungs and naming it “melanose.”

In 1819, he published De l’auscultation médiate, ou Traité du diagnostic des maladies des poumons et du coeur [On mediate auscultation, or a treatise on the diagnosis of diseases of the lungs and heart], a landmark work that identified a range of chest sounds—rales, rhonchi, crepitance, egophony—and distinguished between normal and pathological breath sounds. His work transformed the physical exam from an art of intuition into a science of precision.

After some early opposition to his invention, De l’auscultation médiate and the stethoscope would take off, quickly spreading throughout Europe and the U.S.

Laënnec’s early life was shaped by loss and frailty. At just five years old, he lost his mother to tuberculosis—a disease that would haunt both his family and his future. After the death of his mother, Laënnec’s father sent him to live with his uncle, Dr. Guillaume-François Laënnec, the dean of the medical faculty at the University of Nantes. Despite chronic illness—likely asthma—and frequent fevers, young Laënnec was intellectually gifted and artistically inclined.

While at Nantes, he studied music, carved wooden instruments, and wrote poetry. By age 14, he was already assisting in patient care at the Hôtel-Dieu in Nantes, and by age 18, he was a third-class surgeon at the city’s military hospital.

Encouraged by his uncle and undeterred by his father’s objections to pursuing medicine as a career, Laënnec studied medicine in Paris. There, he trained under some of the era’s most celebrated physicians, including Jean-Nicolas Corvisart-Desmarets, Xavier Bichat, and Guillaume Dupuytren.

Already somewhat frail from his chronic illness, Laënnec further declined after beginning his practice. Medical school and his research had exposed him to numerous tuberculotic patients and cadavers. By 1814, his poor health forced him to return to Brittany to recover in the quiet countryside.

In 1816, Laënnec returned to Paris to take over as the chief of Necker Hospital. It was there that he continued his research into chest diseases and was inspired to create the stethoscope. Prior to his invention, the standard practice for attempting to observe chest sounds was direct auscultation—placing an ear directly on the chest of the patient.

Laënnec appreciated the information that could be assessed through direct auscultation, but not the discomfort and embarrassment it caused both the patient and the physician. It also had its limitations. Laënnec was growing frustrated when inspiration struck. His musical training, woodcarving, and (perhaps apocryphally) recalling a children’s game where someone scratches one end of a tube, sending sounds to another child listening at the other end, combined to create a vision of a listening tube applied to the patient’s chest.

Putting his idea into practice, he quickly rolled up some paper, creating an approximation of a cone. He placed one end of the cone on the patient’s chest and the other to his ear. Voila! A symphony of chest sounds. The musically inclined Laënnec eventually carved a wooden tube with a fluted opening on one end and an earpiece on the other.

As his health continued to fail, in 1824, Laënnec’s nephew examined him, listening to his chest with a stethoscope, and diagnosed him with tuberculosis. In the summer of 1826, Laënnec fell into a coma and died on August 13. His now-famous stethoscope he bequeathed to his nephew.

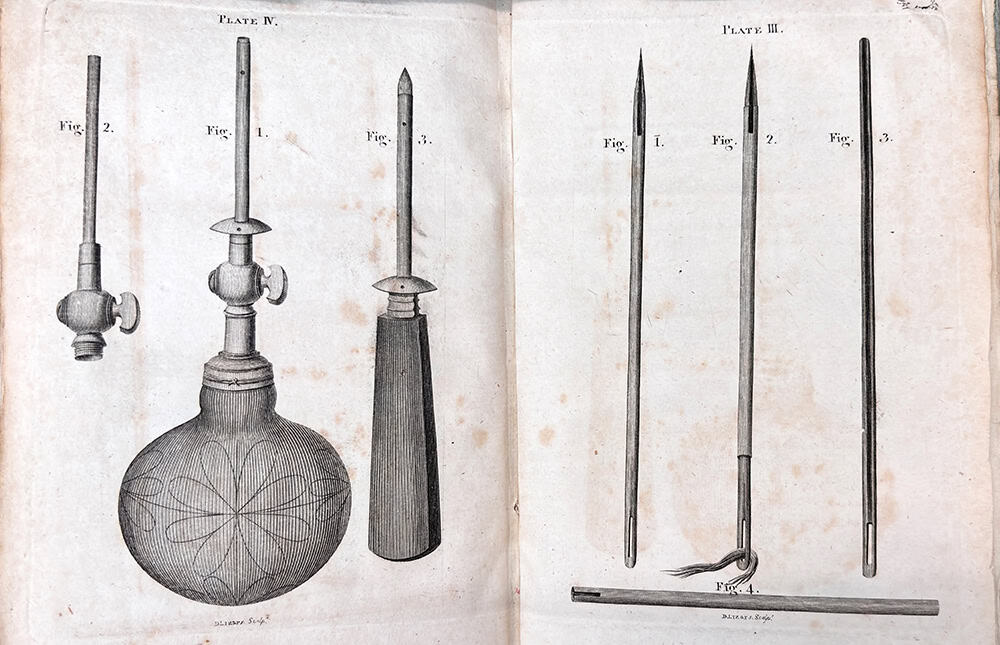

As mentioned, De l’auscultation médiate is a two-volume set. Our copy is in great shape. Both volumes are covered in blue and black marbled paper, and the fore-edge has a lovely dark blue and black speckling. Although the paper isn’t of the highest quality, it has held up well, with only minor foxing and staining. Not surprisingly, the four folded illustrations in the back of volume one have taken the most abuse and are in the roughest shape (although still sturdy and usable).

LAËNNEC, RENÉ (1781–1826). De l’auscultation médiate, ou Traité du diagnostic des maladies des poumons et du coeur. Printed in Paris by J.-A. Brosson et J.-S. Chaudé, 1819. 23 cm tall.

Contact the John Martin Rare Book Room Curator Damien Ihrig at damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154 to see these books in-person or virtually.

We present William Paul Crillon Barton’s (1786–1856) masterwork, Vegetable materia medica of the United States (1817–1818). Barton was a well-known naval surgeon, medical botanist, artist, and professor. He was born on Nov. 17, 1786, in Philadelphia, to a family filled with people who made important contributions to every aspect of the early United States. Barton had both the opportunities and the drive to make his own impact on the new nation.

Growing up, Barton must have heard many stories of his great-uncle, the astronomer, cartographer, inventor, and clockmaker David Rittenhouse (who also became Barton’s grandfather-in-law after Barton married his cousin, Esther). Barton’s father, William, wrote the definitive biography of David Rittenhouse and helped to design the Great Seal of the United States, most famous now for its ubiquity on U.S. dollars and as a plot device in the National Treasure movie.

His uncle, Benjamin Barton, was a well-known physician and botanist whom Barton would eventually study under. And his brother, John Barton, pioneered corrective osteotomy for joint ankylosis and invented the Barton bandage and Barton forceps.

William Barton spent most of his career in the Navy as a surgeon and administrator, eventually working his way up to the head of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, the precursor to the Navy Surgeon General. However, he never lost his love of medicinal plants and eventually published the beautifully illustrated Vegetable Materia Medica, the first U.S. botanical work published with colored plates.

Read below to learn more about the John Martin Rare Book Room’s copy of Vegetable Materia Medica, Barton’s friend (frenemy?) and fellow plant enthusiast Jacob Bigelow, and how Barton played a role in presidential case law.

BARTON, WILLIAM P. C. (1786–1856). Vegetable materia medica of the United States. Two volumes. Printed in Philadelphia by M. Carey & Son, 1817–1818. 28 cm tall.

Barton attended Princeton University and graduated in 1805. While at Princeton, as was customary for all undergrads, he took the name of a celebrated individual—Count Paul Crillon—and kept the initials P. C. for life. [Interestingly, the only Paul Crillon that Damien Ihrigh, curator of the JMRBR, could find information on is the alias for the French spy and con artist, Paul Émile Soubiran, whose scheming helped hasten the start of the War of 1812—and earned him a pile of cash.]

Barton then studied medicine at the University of Pennsylvania under his uncle, Benjamin Barton, who wrote the first American botanical textbook. This sparked Barton’s lifelong interest in botany and desire to publish an illustrated medical botany book devoted to American plant species.

Barton graduated in 1808 with his medical degree. His dissertation on nitrous oxide gas, which included an illustration of a man inhaling “laughing gas,” was influential at a time when such experiments were often mocked.

At age 23, Barton joined the U.S. Navy as a surgeon. He worked to improve medical supplies on ships and pushed for the use of lemons and limes to prevent scurvy, even before the Navy recognized the importance of antiscorbutic (term used in the 18th and 19th centuries for foods known to prevent scurvy) treatments for vitamin C deficiencies developed at sea.

In 1811, Congress established the first naval hospitals, and Barton, ever the stickler for best practices and a properly functioning supply chain, was asked to draft regulations for them. He proposed detailed rules and regulations and was the first to advocate for the hiring of female nurses for the Navy.

He advocated for the U.S. to follow the British model for naval medical facilities, including that all property should be marked with a special designation to prevent theft. From that point forward, all Naval medical supplies were marked “U.S. Naval Hospital.”

After his uncle’s death in 1815, Barton became a professor of botany at the University of Pennsylvania. He also taught at Thomas Jefferson Medical College and served as its dean from 1828 to 1829. He also helped develop the Philadelphia Naval Hospital, the first home for the Naval Academy. By 1824, Barton was appointed to the board that examined Navy surgeon candidates, and in 1830, he became the commanding officer at the Naval Hospital in Norfolk, Virginia.

It was during his time at Penn and the Philadelphia Naval Hospital that Barton became a footnote in the development of U.S. presidential case law, specifically, the Monroe Precedent of 1818. Barton was court-martialed after being accused of two counts of “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman” in relation to his actions securing a staff position for himself at the hospital.

President James Monroe met with Barton twice to discuss the appointment at the Naval Hospital. Subsequently, Monroe was subpoenaed to appear before the judge advocate to testify about those meetings. Monroe is in select company. Only three other sitting presidents have been subpoenaed: Thomas Jefferson (Aaron Burr trial), Richard Nixon (Watergate tapes), and Bill Clinton (Paula Jones lawsuit).

Monroe eventually submitted a written deposition, although it arrived after the court made its decision. Barton was found guilty on one count of acting improperly, but he was acquitted of outright lying and received a mild reprimand.

In 1842, President John Tyler appointed Barton as the first head of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery. He recommended many reforms, including higher standards for Naval physicians and tighter control of medical supplies and alcohol. Not surprisingly, his strict policies on alcohol were unpopular amongst the sailors.

The American physician and botanist, Jacob Bigelow, was Barton’s friend and classmate in medical school. They both trained under Benjamin Barton and developed a passion for medical botany. Bigelow published the first volume of his American Medical Botany in 1817, just after Barton. Barton decided in 1815 to write Vegetable materia medica of the United States to honor his uncle after his death, while Bigelow began his project in the spring of 1816.

Barton’s work, published in an edition of only 500 copies, contained fewer entries than Bigelow’s. This allowed Barton to find enough colorists to hand-color his plates, which were often elegant and preferred by contemporaries.

Bigelow, planning a larger edition, resorted to a color-printing process for some plates. Not all copies of Barton’s work have colored plates; some are partially or entirely uncolored.

Vegetable materia medica was published in eight parts, with the final number issued in March 1819. Some copies contain advertisement leaves indicating the publication details and instructions for binders.

Although a third volume was advertised in 1820, it was never published. Barton’s work depicts 49 different plants, shrubs, and trees in 50 plates, with descriptions of their geographical distribution, appearance, and medical properties.

The JMRBR is lucky enough to have two copies of Vegetable materia medica. The first is covered in one-quarter red leather with marbled paper. It shows some wear and tear with scratched and torn covers and the cover of volume one is partly detached.

The second copy is also covered in one-quarter red leather, but with an accompanying plain brown leather. The paper in both copies is in okay shape, but with quite a bit of foxing throughout.

Contact curator Damien Ihrig to see this book or any others in the collection via email or 319-335-9154.

By Christine Blaumueller, PhD

originally published in the Scientific and Research Communication Core newsletter

Graphical abstracts are used by some publishers such as Lancet and Elsevier, and some journals now request them. Graphical abstracts can help attract audiences to a paper and may be promoted on publisher’s social media or websites.

Sample graphical abstract

Weaver, L., Tran, C. G., Kahl, A. R., Troester, A., Mishra, A., Prakash, A., Brauer, D., Charlton, M. E., Hassan, I., & Goffredo, P. (2025). Patterns of care in patients with asymptomatic stage IV colon cancer: A population-based analysis. Surgery, 184, 109408. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2025.109408

A graphical abstract is a single visual representation that summarizes the most important parts of a study, and it is intended to pique the reader’s interest. As an overview figure for a manuscript, it should be distinct from the other figures and, like a written abstract, it should quickly convey the take-home message. Graphical abstracts are typically designed to accompany journal articles, in which case they provide an opportunity to improve on the abstract by utilizing images. However, graphical abstracts can also serve other purposes. For example, they can be generated to use on a conference poster, enhance a lab website, or share a scientific message on social media.

Below, we briefly summarize some of the key points to consider when generating a graphical abstract. Most of these ideas are illustrated in this video1 from BioRender, and they are also discussed in greater detail in several resources2–5. Note that BioRender provides a library of templates for graphical abstracts; these can be a great starting point. Programs other than BioRender that can be used to generate graphical abstracts include Canva, Microsoft PowerPoint, and Adobe Illustrator2.

Layout and story flow: focus on the key message

Color: keep in mind the associations a reader might make

Highlights: make it easy to spot relevant differences

Other considerations

It may feel daunting to design a graphical abstract but don’t be afraid to get started. Once you do, you might have fun—and you might even come up with new ideas for your project in the process!

If you need help with graphical abstracts, you can contact your Hardin Library for the Health Sciences librarian or the SERCC team.

Resources:

by Riley Samuelson

Now is a great time to back up your EndNote libraries and keep those citations safe!

There are a couple of options for easy backup, syncing with an online account and creating a compressed library.

To set up an account for syncing (works with only one desktop library):

To create a compressed library file:

If you need help backing up your EndNote files or even using EndNote, please contact your Hardin Library for the Health Sciences librarian.

If you want to get started using EndNote, you can also attend a workshop or request an individual session.

Hardin Library for the Health Sciences staff want you to succeed with finals, so we have some ways to make spending time at the library easier.

Later Hours

The library will be open until 9 p.m. on Friday, May 9, and Saturday, May 10. The 24-hour study is available to UI affiliates when the library is closed.

Free coffee and snacks

Free coffee and snacks beginning Friday, May 9, while supplies last!

Find our dinosaur

Be the first person to find our stuffed dinosaur, Little Linda, every day and win a Hardin Library mug. Linda will be hidden from Saturday, May 10, through Thursday, May 14.

Ranch dip taste test

Love ranch dip? Vote for your favorite and register to win a prize snack bag on Sunday, May 11, from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. Prizes sponsored by Lynne Church.

Positive affirmations

We have a whiteboard of affirmations to help you stay positive during this busy time. Take one if you need one!

Group study rooms

Need a group study room? We have 12 that you can reserve online.

And remember, you can always visit Hardin Library’s website for more information, including how to contact a health sciences librarian for assistance, during finals week or anytime throughout the year.

Student employees are a crucial part of what makes the Hardin Library a valuable, accessible resource for the community on campus and beyond. Student employees work and grow alongside Hardin staff, directing users to resources, caring for materials, and contributing new ideas. This year, we are proud to celebrate two of our student employees as they graduate. Get a glimpse into their experiences and goals through the questions and answers below.

Rileigh Corner

Bachelor of Science in environmental science with a certificate in sustainability

Q: What are your favorite activities during your time at Iowa?

A: I am a proud member of the Hawkeye Marching Band!

Q: What are your plans after graduation?

A: I will be working in conservation to improve the landscape in Eastern Iowa.

Q: What did you enjoy about working at Hardin Library?

A: I love how kind and helpful everyone always is, and there is always a smiling face every time I come to work.

Rachel Winey

Bachelor of Arts in English and creative writing with a minor in anthropology and a certificate in museum studies

Q: What is a favorite memory during your time at Iowa?

A: I spent a semester studying abroad.

Q: What are your plans after graduation?

A: I am starting graduate school for library and information science, and then hopefully doing internships at museums around the U.S.

Q: What did you enjoy about working at Hardin Library?

A: I loved the academic environment!

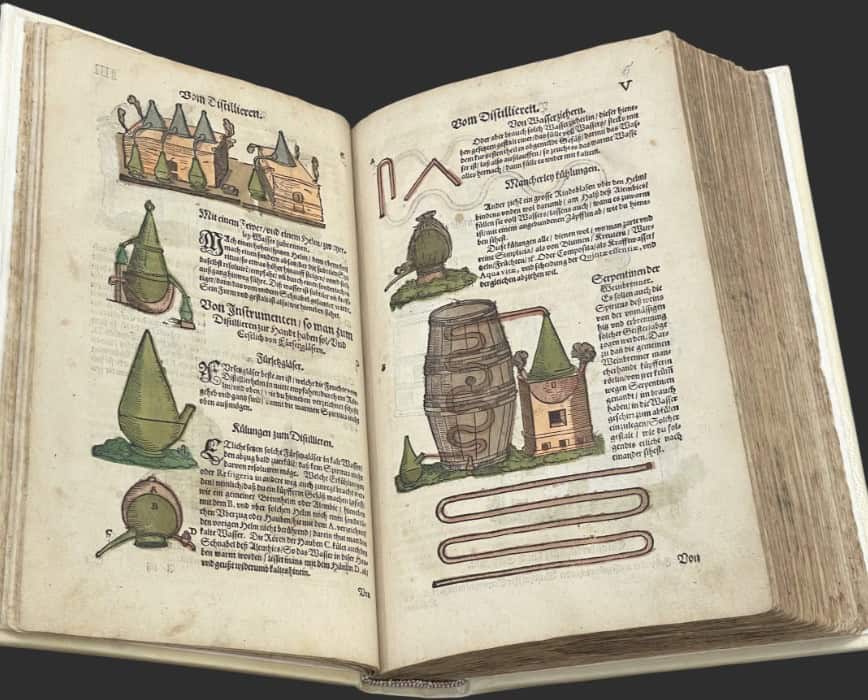

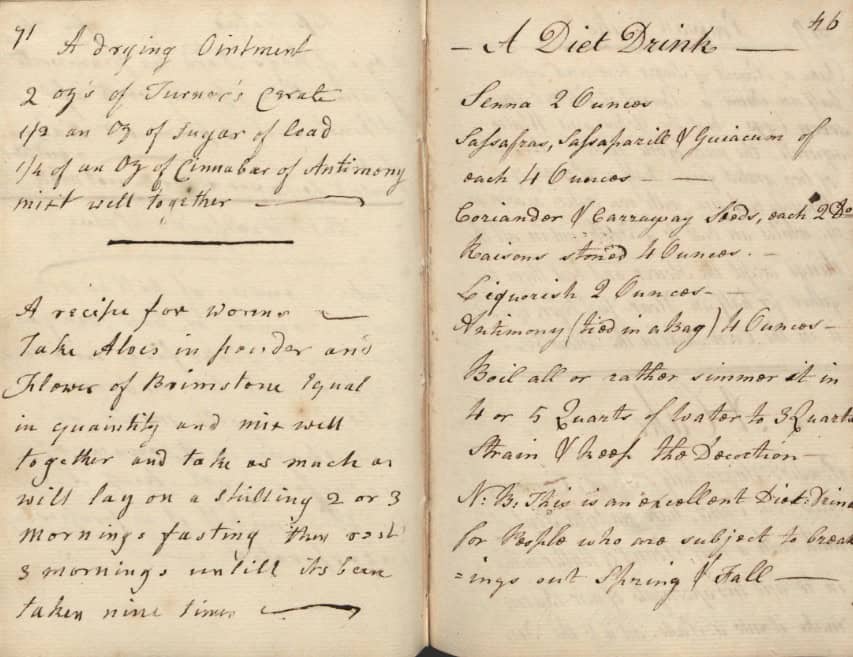

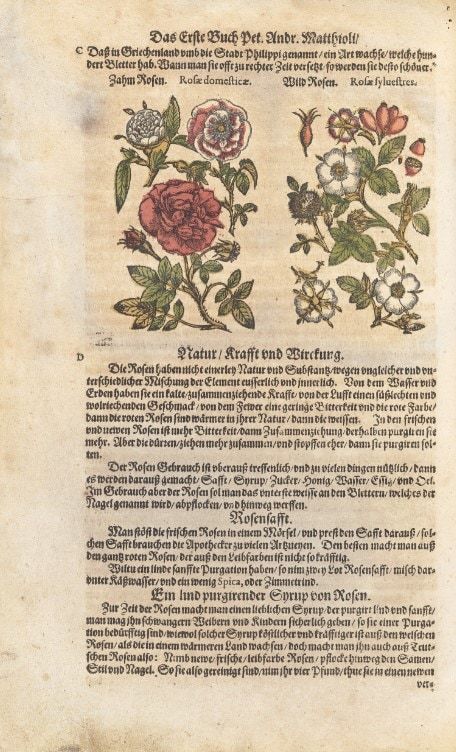

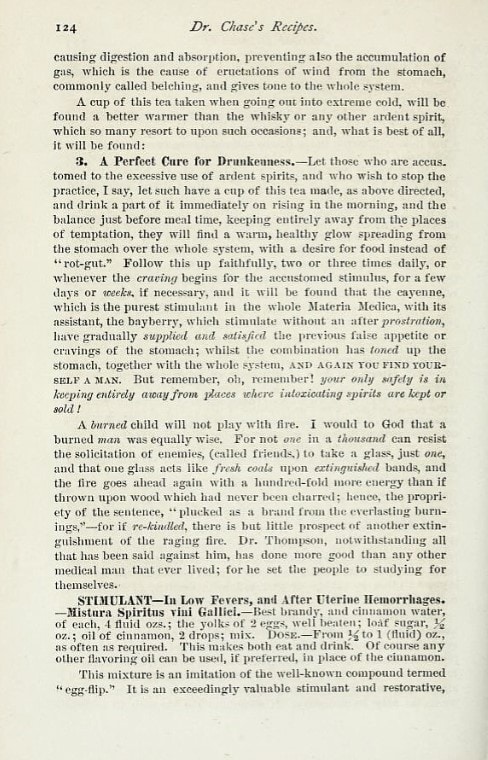

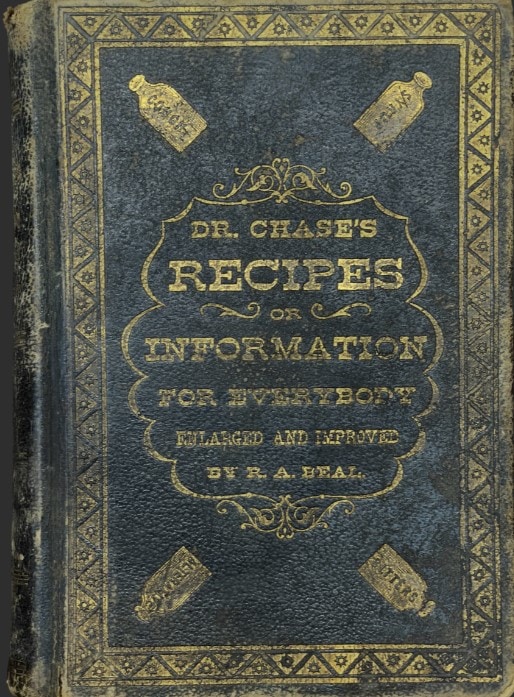

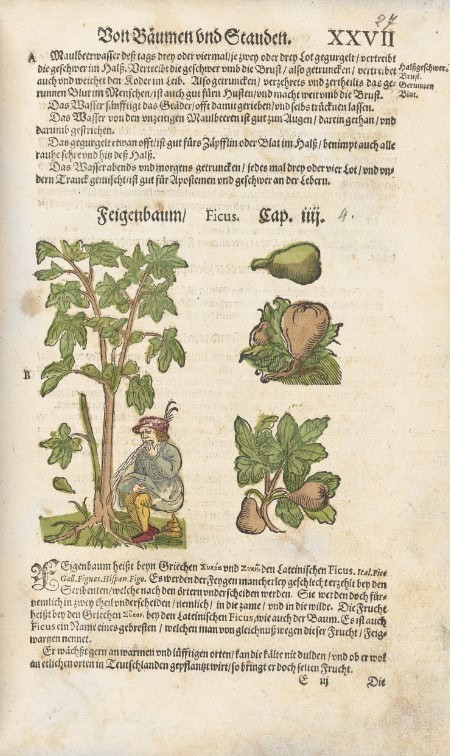

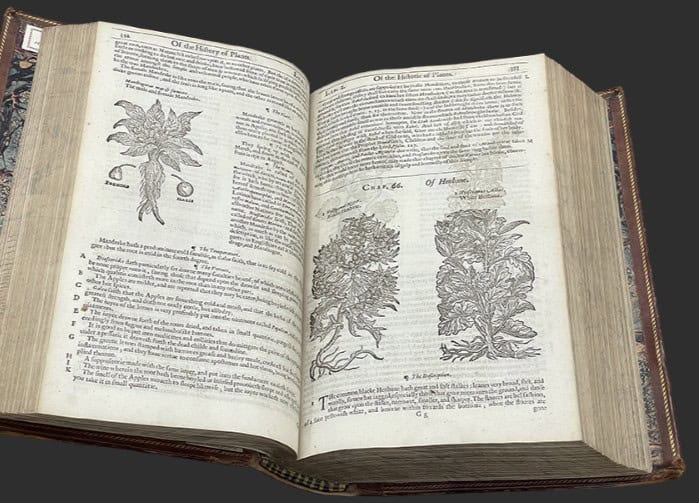

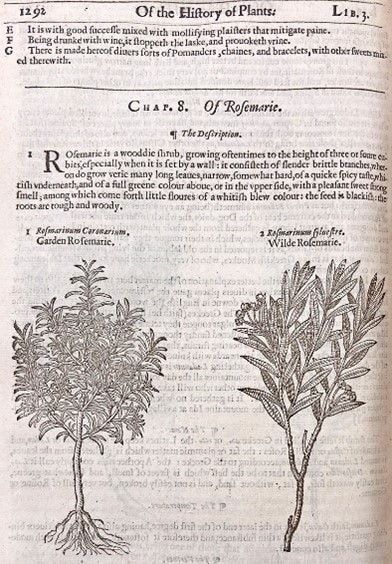

Visit Hardin Library’s new exhibit on the third floor to explore how home remedies developed into pharmacology. Starting with folks in the 16th–19th centuries, whose ailment treatments came from a trusted authority figure and consisted of any number of substances applied in any number of ways, ranging from the helpful to the ineffectual, to the superstitious, and to the deadly. In the West, these might have been applied by a university-trained physician, by a guild-trained apothecary, by a village healer, or at home with remedies passed down through generations.

Long known as Materia Medica, the practice of applying plants, animal products, food, oils, and inorganic substances evolved into the scientific study and application of medicine known as pharmacology. Medieval Arabic and Western physicians referred to uncomplicated medicines or medicinal compounds as simples. Early recipes often incorporated superstitions, astrology, or other aspects of the occult. The phase of the moon, position of the planets, or the condition of the patient—for example, were they sick due to physical reasons or from demonic possession—could all determine the type of medicine, its composition, or its method of application.

As medicine evolved, creating medicines and treating the sick became more systematic and scientific. Parallel to this evolution was the consolidation of power by physicians and the marginalization of other healing practitioners, consisting of many women who were barred from attending universities. Nevertheless, home remedies continued to be passed down from generation to generation in family recipe books. Eventually, physicians would cater to this market by collecting home remedies and sharing them in their own books. Examples of these books are listed below and you can visit Hardin’s new exhibit to see these books and more.

Brunschwig, Hieronymus (ca. 1450-ca.1512). A most excellent and perfecte homish apothecarye or homely physick booke for all the grefes and diseases of the bodye. Printed in Cologne by Arnold Birckman, 1561.

FOLIO R128.6 .B813 1561

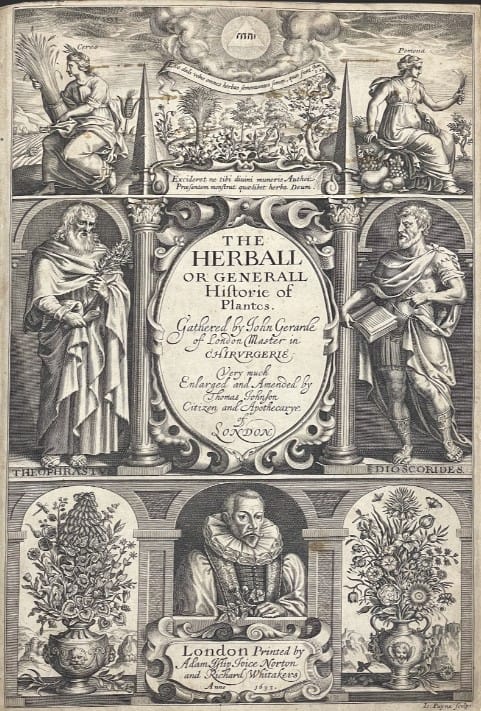

Gerard, John (1545-1612). The herball or Generall historie of plantes. Printed in London by Adam Islip, Joice Norton, and Richard Whitakers, 1633.

FOLIO QK41 .G3 1633

Lonicer, Adam (1528-1586). Kreuterbuch, kunstliche Conterfeytunge der Bäume, Stauden, Hecken, Kreuter, Getreyde, Gewürtze. Printed in Frankfurt by the Heirs of Christian Egenolff, 1587.

FOLIO QK41 .L66 1587

Barton, William P. C. (1786-1856). Vegetable materia medica of the United States. 2 volumes. Printed in Philadelphia by M. Carey, 1817-1818.

QK99 .B3 1818

Buc’hoz, Pierre-Joseph (1731-1807). The toilet of flora: or a collection of the most simple and approved methods of preparing baths, essences, pomatums, powders, perfumes, and sweet-scented waters. With receipts for cosmetics of every kind, that can smooth and brighten the skin, give force to beauty, and take off the appearance of old age and decay. For the use of ladies. Printed in London, 1779.

TP983 .B83 1779

Chase, Alvin W. (1817-1885). Dr. Chase’s Recipes, or, Information for Everybody. Printed in Ann Arobor by R.A. Beal, 1880.

TX153 .C49 1880

Fowler, Charles H. (1837-1908) and De Puy, William H. (1821-1901). Home and health and home economics : a cyclopedia of facts and hints for all departments of home life, health, and domestic economy. Printed in Cincinnati by Hitchcock and Walden, 1880.

TX153 .F68 1880

Exhibit curated by Damien Ihrig, Catherine Reed-Thureson, and Helen Spielbauer.

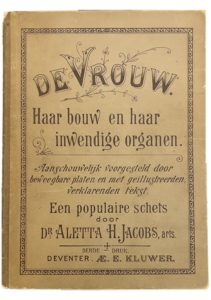

This Women’s History Month, the John Martin Rare Book Room highlights a book from the pioneering 19th-century Dutch physician and activist Aletta Jacobs. Born in 1854 in the Netherlands, Jacobs chafed at the status quo and the limited educational opportunities for women in the Netherlands. She rejected the standard for Dutch girls at the time, “finishing school,” and instead studied at home with her parents.

From a young age, Jacobs was determined to pursue her dream of becoming a doctor like her father. At the time, though, women were barred from higher education. To become a doctor meant that she would have to achieve many firsts for the Netherlands.

She first earned a diploma in pharmacy in 1869. She requested admission to the University of Groningen through a letter-writing campaign by herself and her father. She was finally told to continue her studies for two more years to prepare for the entrance exam. Through this provisional admission, she was able to convince a local high school to allow her to attend classes, becoming the first Dutch woman to attend secondary school.

In 1871, she caught wind of a male student granted admission to the University of Groningen based on his pharmacy diploma. She was granted approval to attend and became the first woman to enroll at the University of Groningen. Despite challenges and resistance from male students and professors, she graduated in 1879, earning her medical degree.

Throughout her career, she was a forceful supporter of social reforms. She was an unyielding advocate for the health of women and children as well as suffrage and international peace. She wrote many articles and books, including De Vrouw: Haar bouw en haar inwendige organen [The Woman: Her physique and her internal organs], a short book about female anatomy.

JACOBS, ALETTA (1854-1929). De vrouw: haar bouw en haar inwendige organen [The Woman: Her physique and her internal organs]. Printed in Deventer by Ebele E. Kluwer, 1900. 26 cm tall.

In 1882, Jacobs founded the world’s first birth control clinic in Amsterdam. She believed that women should have control over their reproductive health. Her clinic provided education and resources about contraception, which was a revolutionary idea at the time.

Not content with the birth control options for women at the time, she created and tested a new diaphragm. Establishing its effectiveness, it became a popular birth control choice for women and eventually was known throughout the English-speaking world as the Dutch Cap.

Jacobs was a strong supporter of women’s right to vote. She began her campaign for suffrage in 1883, challenging the legal barriers that prevented women from participating in politics.

Her efforts contributed significantly to the eventual success of the women’s suffrage movement in the Netherlands, culminating in women gaining the right to vote in 1919.

Jacobs was also involved in international peace movements. She participated in international conferences aimed at promoting peace and disarmament, believing that women’s voices were crucial in these discussions. She argued that women had a unique perspective on peace and should be included in decision-making processes.

De vrouw was written to offer a more thorough and accurate understanding of the female body, highlighting both external features and internal organs through detailed illustrations and explanatory text. It focuses on women’s anatomy, especially the structure and function of the female reproductive system, addressing the significant knowledge gap many women had about their own bodies.

De vrouw begins with a foreword by Jacobs, who expressed concern over the widespread ignorance about women’s bodies, even among the educated. Jacobs aimed to provide a concise and accessible resource to satisfy the public’s curiosity and need for information.

The text aimed to deliver clear descriptions supported by illustrations, stressing the importance of understanding both the general framework of human anatomy and the specific details of female organs. This introduction sets the stage for a detailed exploration of human anatomical structures, emphasizing the need for better education on the subject.

The book is slim in form, with the text block snuggled between two stiff paper boards. The whole thing is held together with a pamphlet-type stitch with a lovely and vibrant red thread. It is chock full of illustrations, including a thorough flap illustration shown in the photo below. The copy in the John Martin Rare Book Room is in stable condition, although, as can also be seen in the image below, the back cover has separated.

Contact Damian Ihrig, curator of the John Martin Rare Book Room, to take a look at this book: damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154.

Reil, was an 18th-century medical multihyphenate: physician-anatomist-physiologist. He was also the first true psychiatrist by virtue of coining the term “psychiatry” (or “psychiatrie” in German). His contributions to anatomy include the first description of the arcuate fasciculus in 1809 and the identification of anatomical features such as Reil’s finger (later known as Raynaud syndrome) and the Islands of Reil in the cerebral cortex.

Reil’s philosophical perspective on mental illness evolved in the context of the Romantic movement, blending scientific inquiry with a deeper appreciation of life’s poetic and tragic aspects. In 1803, Reil published Rhapsodieen über die Anwendung der psychischen Kurmethode auf Geisteszerrüttungen [Rhapsodies on the Application of Psychological Methods of Cure to the Mentally Disturbed], a seminal work that significantly influenced German psychiatry before Sigmund Freud. Not a one-hit wonder, Reil was also an active editor and orchestrated several medical journals, including two devoted to psychiatry.

Rhapsodieen is characterized by its rich metaphors and ironic tone, which stood apart from typical medical treatises of the time. In it, he proposed indirect psychological methods to treat mental illness, emphasizing the role of social conditions and the harmony of the mind’s functions. Reil often proposed ways to shock the system for patients with dissociative-type or catatonic disorders. His hypothesis was that the shock would jolt the patient and bring them back to conscious awareness.

REIL, JOHANN CHRISTIAN (1759-1813). Rhapsodieen über die Anwendung der psychischen Kurmethode auf Geisteszerrüttungen [Rhapsodies on the Application of Psychological Methods of Cure to the Mentally Disturbed]. Printed in Halle: In der Curtschen Buchhandlun, 1818. 23 cm tall.

Born in East Friesland, Reil began his university studies at Göttingen in 1779 but soon transferred to Halle, where he was influenced by the anatomist Philipp Friedrich Meckel and became close friends with Johann Friedrich Goldhagen. After earning his medical degree in 1782, Reil continued his studies in Berlin, where he engaged with the intellectual circles of Marcus Herz and the critical philosophy of Immanuel Kant.

Reil’s career flourished upon his return to Halle in 1787, where he quickly rose to become the director of the clinical institute and chief physician of the city. His medical practice attracted many prominent patients, including Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and his innovative ideas began to take shape.

Reil’s theories on mental illness and treatments evolved over time. He wrote several volumes on fevers influenced by Kant and others. This included his theories on the connection between fevers and mental illness. Eventually, he would be swayed by the German romantic movement of the time and his theories became more fanciful, with treatments to match.

First published in 1803, Rhapsodieen is one of the earliest systematic works on psychotherapy. In it, Reil sets forth principles and different techniques of therapy. Although he did not formulate a comprehensive theory of personality, he recognized the necessity of understanding the healthy personality before the pathological personality could be understood. He believed that mental illness is a psychological phenomenon that requires psychological methods of treatment and was convinced of the close relationship between mind and body.

Even though he espoused many enlightened views, including advocating for improving the horrific conditions of patients who resided in asylums, his therapeutic procedures are considered crude by today’s standards.

His work is considered by some to represent the beginnings of modern psychotherapy, although he is often eclipsed by Pinel and his Traité médico-philosophique sur l’aliénation mentale; ou la manie [Medical-philosophical treatise on insanity, or mania], considered a more practical work. Reil and Pinel developed a healthy rivalry that helped inform both of their practices.

Our copy of Rhapsodieen is in decent condition. The cover has marbled paper over thin boards and shows quite a bit of wear and tear. The boards appear to be meant as a temporary cover, so that is not surprising. The paper is in pretty good shape, with mostly minor discolorations throughout. Interestingly, some of the gatherings are “unopened,” with the tops of the pages still connected. Many of the pages also still have deckled edges, giving a rough and ready look.

Contact our curator to view this book at damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154.

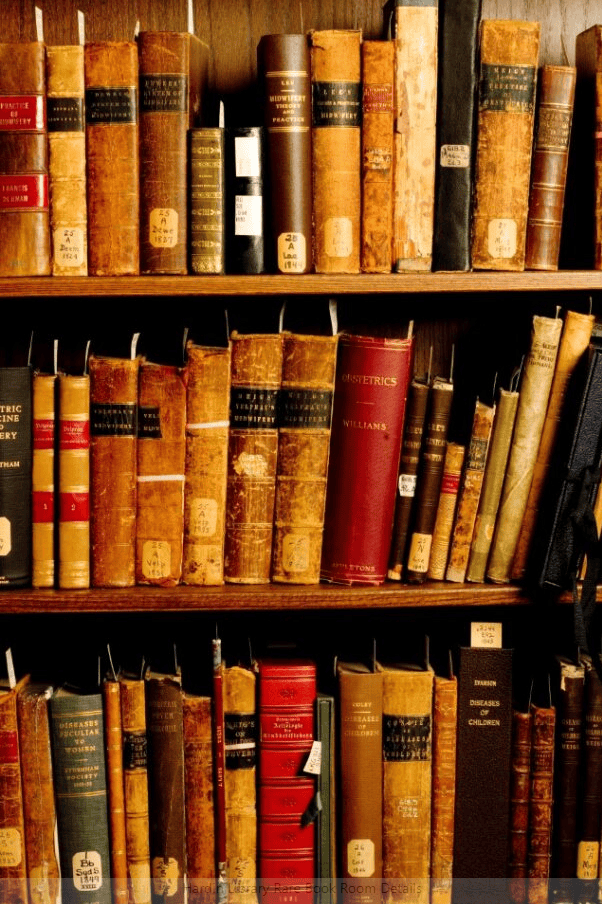

The annual John Martin Rare Book Room (JMRBR) open house will be on Thursday, April 24, 2025. All are invited to drop in from 5:30 to 8 p.m. to tour the space and explore staples of the JMRBR collection. There will also be special materials on display, such as John Gerard’s The herball and Brunschwig’s A most excellent and perfecte homish apothecarye, that will highlight historical examples of medicinal recipes, apothecaries, home remedies, poisons, and herbal medicine.

The JMRBR’s nearly 7,000 volumes of original works represent classic contributions to the history of the health sciences from the 15th–21st centuries. The collection includes selected books, reprints, and journals dealing with the history of medicine at the University of Iowa and in the state of Iowa.

Individuals with disabilities are encouraged to attend all University of Iowa–sponsored events. If you are a person with a disability who requires a reasonable accommodation in order to participate in this program, please contact Damien Ihrig in advance at 319-335-9154 or damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu.

In 2024, six of the librarians on staff at the Hardin Library for the Health Sciences have been listed as co-authors of published research. We’re always excited to collaborate with our library users, whose important work energizes all of us. Further information is listed below, and academic publications affiliated with the University of Iowa can be found anytime using Iowa Research Online.

Chris Childs

Mendes, M. S. S., Ferreira, C. L., Jardini, M. A. N., Childs, C. A., & Marchini, L. (2025). Ageism combating strategies in oral healthcare: A systematic review. Special Care in Dentistry, 45(1). https://doi.org/10.1111/scd.13094

Ghannam, M., AlMajali, M., Khasiyev, F., Dibas, M., Al Qudah, A., AlMajali, F., Ghazaleh, D., Shah, A., Fayad, F. H., Joudi, K., Zaidat, B., Childs, C. A., Levy, B. R., Abouainain, Y., Özdemir-van Brunschot, D. M. D., Shu, L., Goldstein, E. D., Baig, A. A., Roeder, H., … Yaghi, S. (2024). Transcarotid Arterial Revascularization of Symptomatic Internal Carotid Artery Disease: A Systematic Review and Study-Level Meta-Analysis. Stroke (1970). https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.044246

Brown, E., Stuhr, S., Chambrone, L., Childs, C. A., Avila-Ortiz, G., & Elangovan, S. (2024). Publication Delay of Systematic Reviews in Dentistry: Findings, Implications, and Potential Solutions. The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry, 44(3), 252–255. https://doi.org/10.11607/prd.2024.3.c

Desai, J., Marchini, L., Childs, C., & Kohli, R. (2024). Randomized Controlled Trials in Geriatric Dentistry – 11. In Randomized Controlled Trials in Evidence-Based Dentistry (pp. 225–243). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47651-8_11

Ghannam, M., Al-Qudah, A. M., Alshaer, Q. N., Kronmal, R., Ntaios, G., Childs, C. A., Longstreth, W. T., Alsawareah, A., Keller, T., Serna-Higuita, L. M., Geisler, T., Furie, K., Saver, J. L., Kasner, S. E., Elkind, M. S. V., Tirschwell, D., Poli, S., Kamel, H., & Yaghi, S. (2024). Anticoagulation vs Antiplatelets Across Subgroups of Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Neurology, 103(9). Buck, H. G., Howland, C., Stawnychy, M. A., Aldossary, H., Cortés, Y. I., DeBerg, J., Durante, A., Graven, L. J., Irani, E., Jaboob, S., Massouh, A., da Costa Ferreira Oberfrank, N., Saylor, M. A., Wion, R. K., & Bidwell, J. T. (2024). Caregivers’ Contributions to Heart Failure Self-care: An Updated Systematic Review. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 39(3), 266–278. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0000000000001060https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000209949

Selvamani, B. J., Kalagara, H., Volk, T., Narouze, S., Childs, C., Patel, A., Seering, M. S., Benzon, H. T., & Sondekoppam, R. V. (2024). Infectious complications following regional anesthesia: a narrative review and contemporary estimates of risk. Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1136/rapm-2024-105496

Curtis, G., Weber, H., Tran, V., Childs, C., Shin, K., & Garaicoa-Pazmino, C. (2024). Impact of Non-Surgical and Surgically Assisted Rapid Maxillary Expansion Procedures upon the Periodontium: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 14(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/app14041669

Jennifer Deberg

Vignato, J., Martin, T., Garton, M., Deberg, J., Dehner, H., Thompson, M., & Conley, V. (2024). A Systematic Review of Pain and Depression Symptoms During the Perinatal Period. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2024.01.202

Heather Healy

Faro, E. Z., Taber, P., Seaman, A. T., Rubinstein, E. B., Fix, G. M., Healy, H., & Reisinger, H. S. (2024). Additional file 4 of Implicit and explicit: a scoping review exploring the contribution of anthropological practice in implementation science [dataset]. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26680037

Faro, E. Z., Taber, P., Seaman, A. T., Rubinstein, E. B., Fix, G. M., Healy, H., & Reisinger, H. S. (2024). Implicit and explicit: a scoping review exploring the contribution of anthropological practice in implementation science. Implementation Science : IS, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-024-01344-0

Vakkalanka, J. P., Gadag, K., Lavin, L., Ternes, S., Healy, H. S., Merchant, K. A. S., Scott, W., Wiggins, W., Ward, M. M., & Mohr, N. M. (2024). Telehealth Use and Health Equity for Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health, 30(5), 1205–1220. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2023.0588

Lavin, L., Gibbs, H., Vakkalanka, J. P., Ternes, S., Healy, H. S., Merchant, K. A. S., Ward, M. M., & Mohr, N. M. (2024). The Effect of Telehealth on Cost of Health Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Telemedicine Journal and E-Health. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2024.0369

Ternes, S., Lavin, L., Vakkalanka, J. P., Healy, H. S., Merchant, K. A., Ward, M. M., & Mohr, N. M. (2024). The role of increasing synchronous telehealth use during the COVID-19 pandemic on disparities in access to healthcare: A systematic review. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X241245459

Damien Ihrig & Helen Spielbauer

Ihrig, D., & Spielbauer, H. (2024). 50 Years: Hardin Library for the Health Sciences. University of Iowa Libraries. [poster]

https://iro.uiowa.edu/esploro/outputs/eventposter/50-Years-Hardin-Library-for-the/9984572770402771#file-0

Matt Regan

De Rosa, P., Kent, M., Regan, M., & Purohit, R. S. (2024). Vaginal Stenosis After Gender Affirming Vaginoplasty – A Systematic Review. Urology (Ridgewood, N.J.), 186, 69–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2024.02.005

Riley Samuelson

Barsotti, E., Goodman, B., Samuelson, R., & Carvour, M. L. (2024). A Scoping Review of Wearable Technologies for Use in Individuals With Intellectual Disabilities and Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy. Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1177/19322968241231279

Santhanam, H., Muthukumarasamy, N., Hsieh, M. K., Brust, K., Wellington, M., Naito, T., Samuelson, R. J., Marra, A. R., & Kobayashi, T. (2024). Systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of infectious diseases consultation on outcomes of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in children. Antimicrobial Stewardship & Healthcare Epidemiology : ASHE, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2024.450

Simonsen, D., Livania, V., Cwiertny, D. M., Samuelson, R. J., Sivey, J. D., & Lehmler, H.-J. (2024). A systematic review of herbicide safener toxicity. Critical Reviews in Toxicology, 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408444.2024.2391431

VanWiel, L., Unke, M., Samuelson, R. J., & Whitaker, K. M. (2024). Associations of pelvic floor dysfunction and postnatal mental health: a systematic review. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 1-. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2024.2314720

Bolton, A., Paudel, B., Adhaduk, M., Alsuhaibani, M., Samuelson, R., Schweizer, M. L., & Hodgson-Zingman, D. (2024). Intravenous Diltiazem Versus Metoprolol in Acute Rate Control of Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter and Rapid Ventricular Response: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized and Observational Studies. American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs : Drugs, Devices, and Other Interventions, 24(1), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40256-023-00615-3

Berg, A., Ebach, D., Justice, N. A., Smelser, A., Samuelson, R., Mahmood, Z., & Imdad, A. (2024). Management of pediatric patients admitted for colonic disimpaction: A scoping review protocol. JPGN Reports, 5(3), 265–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/jpr3.12094

Schanz, W., Akhter, A., Richardson, G., Story, W., Samuelson, R., & Imdad, A. (2024). Perceptions of families and healthcare providers about feeding preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit: protocol for a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open, 14(6). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-084884

Mary M Thomas

Weber, A. N., Trebach, J., Brenner, M. A., Thomas, M. M., & Bormann, N. L. (2024). Managing Opioid Withdrawal Symptoms During the Fentanyl Crisis: A Review. Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation, 15, 59–71. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S433358

Hardin Library for the Health Sciences director Janna Lawrence retired on Nov. 1, 2024. While at Hardin Library, Janna greatly increased Hardin’s teaching and outreach as well as oversaw renovations to all floors of the library.

Janna is an award-winning librarian with many professional accomplishments, including being named a fellow of the Medical Library Association (MLA) in 2021, which recognized her career and work to the organization. Some of her other career highlights include:

· MLA President’s Award, 2020

· MLA Virginia L. and William K. Beatty Volunteer Service Award, 2014

· MLA Board member, 2021–2024

· Editorial Board, Journal of the Medical Library Association

· Midwest Chapter MLA president, 2011

You can read Janna’s publications in Iowa Research Online.

Janna is relocating to San Antonio, Texas, to live near her family. We wish her well!

by Mary M. Thomas, clinical education librarian

Struggling to keep up with new publications? Try BrowZine on your phone, tablet, or desktop.

BrowZine is a website and app enabling you to easily browse, read, and monitor scholarly journals. The app is available for iOS, Android, and Kindle Fire devices. BrowZine is like a virtual newsstand for scholarly journals. It’s a terrific tool for organization, you can create bookshelves for your journals. It’s a wonderful tool for keeping current, keeping track of your progress in journals as well as alerting you to new articles. Plus, you can download full text articles to read later offline.

On desktops:

On mobile devices:

If you need help with BrowZine, contact us!

ClinicalKey added many new electronic book titles this summer. Find these titles by searching in InfoHawk+.

ClinicalKey is available as a mobile app for your device at no charge due to the library’s subscription.

BLANCO, MANUEL (1779–1845). Flora de filipinas. Printed in Manila at the Santo Tomas press, 1837. 21 cm tall.

Manuel María Blanco Ramos was born on Nov. 24, 1779, in Navianos de Alba, a small village in the province of Zamora, Spain. Blanco grew up in Spain, influenced by King Charles III’s commitment to humanism and scientific progress. Despite the turbulence of the 19th century, Blanco emerged as a prodigious figure driven by a desire to serve his parishioners and explore the natural world.

At the age of 10, Blanco entered the College-Seminary in Valladolid, where he studied Latin and philosophy. His thirst for knowledge extended beyond theology; he immersed himself in various scientific disciplines, including chemistry, physics, natural history, mathematics, geography, and astronomy.

After completing his Augustinian training in 1804, Blanco left for the Philippines. Arriving in Manila in 1805, the local Catholic parish assigned him to a monastery in the town of Angat in the province of Bulacan. His primary task was to learn the Tagalog language under the guidance of Brother Joaquín Calvo, who shared Blanco’s passion for plants.

In 1822, he translated Tissot’s Treatise on Domestic Medicine from French to Tagalog. His goal was to incorporate locally available remedies, bypassing those inaccessible to the indigenous population. Given the abundance of local vegetation, he focused on indigenous plants with healing properties.

Blanco meticulously observed the country’s vegetation. He collected plant specimens, took notes, and documented his findings. He lacked formal training as a professional botanist and had no mentors or herbaria for reference. Armed only with Carl Linnaeus’s System Vegetabilium and later Jussieu’s Genera Plantarum, he embarked on a quest to catalog every plant in the Philippines.

His work culminated in the monumental work Flora de Filipinas, según el sistema sexual de Linneo [Flora of the Philippines according to Linnaeus’s system]. This comprehensive work cataloged over 900 plant species, providing valuable insights into Philippine botany.

Father Blanco included common names in Tagalog, Bicol, Visayan, Ilocano, and Pampango alongside scientific nomenclature. Observations included medicinal and practical applications.

Although initially reluctant to publish his work, his fellow friars eventually convinced him that his book would significantly contribute to the scientific understanding of the Philippines. The book proved very popular and Blanco soon started work on a slightly expanded and improved second edition. Unfortunately, he would not finish the book before his death.

Blanco spent the final years of his life in poor health due to a prolonged bout of dysentery. He died on April 1, 1845, at the age of 66.

He had worked diligently on his expanded and corrected second edition, which was nearly complete. His fellow friars finished the book and printed it later that year.

Although Blanco’s herbarium collection no longer exists, Flora de Filipinas remains a testament to his passion for botany and for providing useful medical information to the people of the Philippines.

The John Martin Rare Book Room’s copy of Flora is covered in limp vellum, with the title handwritten on the spine. It is, in modern parlance, chonky—it stands only 21 centimeters tall but is almost 900 pages long! Most of the paper is good quality and sturdy, and although it appears the book may have been resewn and the pages possibly washed, the cover is contemporary with the printed text.

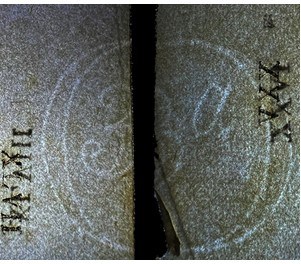

The pages also contain many watermarks possibly from as many as nine separate papermakers. Identifying watermarks can be a bit tricky. Some are well-documented and we know exactly who they belong to. Thanks to the Filigranas Hispánicas watermark database and other watermark databases, I could identify the following watermark as Roman Romani, an 18th-century family of papermakers in Málaga, Spain.

I got lucky, though, because the Romani’s signed their work with their full name. Many watermarks are not so straightforward. The heart you see below is cataloged in a few different places, but I could not find who it belongs to.

The tall mark in gold below is a good example of a variation on a theme—three circles, initials for the papermaker, and topped by the Genoese coat of arms (two griffins on either side of a cross topped by a crown). The Republic of Genoa in Italy was a major European hub for papermaking and mercantile shipping, so there are a lot of examples of this style of watermark.

Unfortunately, I haven’t yet identified which mill the initials SP correspond to. Same with the M with the vine beneath it and the 3a and IB watermarks. But the search is the fun part!

Contact me to take a look at this book: damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154.

Hardin Library has an enrichment collection to stimulate the mind and expand perspectives. The collection, which includes both print and electronic books, contains an assortment of health sciences biographies, histories, narratives, works of fiction, and graphic novels.

|

Mark Onken, administrative library assistant A few weeks ago, I started an ambitious project. Both from watching HBO’s Rome, and from reading my daughter’s Percy Jackson series, I have been on a bit of a Roman history kick, and I have started to read Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans. I have read the first 200 pages (out of 1200), although I think I will give myself a break and read something a little less serious for a week. |

|

Kathleen Halbach, interlibrary loan supervisor I usually have multiple books going at one time.

Over the weekend I finished For the Love of Summer by Susan Mallery. |

|

Matt Regan, clinical education librarian I’m currently reading Shakespeare: The World as Stage by Bill Bryson and the Vlad Taltos series by Steven Brust. |

|

Jennifer DeBerg, user services librarian I just read Akhil Sharma’s “A Life of Adventure and Delight” and am going to start on Lorrie Moore’s “A Gate at the Stairs” soon. A few good ones I have read from Enrichment Collection: |

|

Janna Lawrence, director I’m currently listening to The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams. Next up is No One Goes Alone by Erik Larson. |

|

Damien Ihrig, curator, John Martin Rare Book Room I am reading Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel. |

|

Cassie Reed Thureson, health sciences reference and research librarian I am reading the second book of the Einburgh Nights series, Our Lady of Mysterious Ailments, by T.L. Huchu. |

|

Sarah Andrews, program coordinator I like to read mystery series. I am currently reading Miss Aldridge Regrets by Louise Hare, and the Aimee Leduc Investigations series by Cara Black. I just finished Pay Dirt by Sara Paretsky. I also started Babylon Berlin by Volker Kutscher in preparation for watching the tv series. |

Congratulations to Jennifer DeBerg, user services librarian at Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, on co-authoring a new article that helps update processes for evidence-based nursing.

Evidence-based practice in nursing involves providing holistic, quality care based on the most up-to-date research and knowledge rather than traditional methods, advice from colleagues, or personal beliefs.

Currently, a pyramid hierarchy is typically used when reviewing evidence for a patient’s care. In their article, DeBerg and her co-authors suggest weighing all types of evidence similarly and not categorizing evidence according to an unhelpful evidence hierarchy.

Edmonds, S. W., Cullen, L., & DeBerg, J. (2024). The problem with the pyramid for grading evidence: The evidence funnel solution. Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing, 39(3), 484–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jopan.2023.10.015

You can find more academic publications affiliated with the University of Iowa anytime using Iowa Research Online.

The Medical Library Association (MLA) held a hybrid meeting in Portland, Oregon from May 18 to May 21, 2024. Many of Hardin’s librarians participated in the meeting.

This year’s meeting marked the end of Hardin Director Janna Lawrence’s three-year term on the MLA Board.

Hardin librarian Mary M. Thomas presented a program overview of the UI Libraries’ mental health first aid model. As part of the implementation, Thomas created mental health toolkits for faculty and staff and students.

MARTINEAU, HARRIETT (1802-1876). Life in the sick-room: Essays. Printed in Boston by L.C. Bowles and W. Crosby, 1844. 20 cm tall.

Martineau was born in 1802 into a progressive Unitarian family in Norwich. Despite the societal expectations that confined her to domestic roles, Harriet’s intellect and determination were undeniable. In 1823, she challenged gender norms by anonymously publishing On female education, advocating for women’s rights to education and intellectual pursuits.

Her literary breakthrough came with the publication of Illustrations of political economy in 1832, a series of short stories that deftly wove economic theories into narratives about everyday people. This work not only brought her fame and financial security but also highlighted her as a significant intellectual force.

From 1834 to 1836, Martineau traveled across the United States. A staunch abolitionist and advocate for women’s rights, she wrote extensively against slavery and the lack of opportunities for women, eventually writing Society in America. Her extensive travels also led to insightful writings on the Middle East, India, and Ireland, further establishing her as a versatile and influential journalist and author.

Martineau began experiencing a series of symptoms while on her travels and, in 1839, returned to England for treatment. For someone experiencing a debilitating illness but not necessarily dying, being confined to a “sick room” was common at this time. It allowed the room to be set to the orders of the physician and made it easier for the family to care for their ill relative.

Although confined to her own sick room for five years, Martineau was financially secure and had a progressive, independent spirit. She oversaw her medical care and constructed an environment that best suited her needs. She even restricted access from her family, who she felt could be more emotionally draining than helpful. While resting and recuperating, Martineau remained very productive, writing a novel for children and the essays eventually published in Life in the sick-room.

Already considered an irritation in the medical community, she really caused a stir by claiming that Mesmerism, a pseudo-science medical treatment, cured her. Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815), a German physician, maintained that an “animal magnetism” pervades the universe and exists in every living thing.

He believed that its transmission from one person to another could cure various nervous disorders through its healing properties. Mesmer at first used magnets, electrodes, and other devices to effect his cures, but after arousing suspicion among his fellow physicians, he preferred to utilize his hands.

Considered quackery by many in the medical establishment, even in 1844—including by her physician brother-in-law who oversaw her care—physicians publicly attacked Martineau’s claims about Mesmerism. Her brother-in-law eventually published a detailed account of her illness. Although he promised it would anonymously appear in a medical journal, he instead created a public pamphlet and made little effort to disguise who he was talking about.

After ten years of good health, Martineau once again fell ill in 1855 and returned to her sick room. She remained there until her death in 1876. She continued to write during this time, completing, among other things, her autobiography, works promoting women’s suffrage, and critiques of the Contagious Diseases Acts, which targeted women in the name of preventing sexually transmitted illnesses.

After her death, the medical establishment, again including her brother-in-law, who publicly published the results of an unauthorized autopsy, went out of their way to discredit Martineau and her work. Without evidence, they claimed her illness led her to behave in unconventional and “unfeminine” ways. Martineau remained an inspiration to many, though, and her works live on as a testament to her resilience and rejection of the status quo.

Our copy of the first American edition of Life in the sick-room is quite unassuming. It features a standard 19th-century burgundy cloth cover that has faded over time. Since it was a book in the library’s circulating collection for most of its life, it features a “library cloth” rebacked spine with the label maker-printed call number and title easily visible. Inside, the paper is in good condition, with evidence of damage from a long-ago liquid spill. Much like Martineau herself, though, this little book has shown great resilience in the face of adversity!

Contact the JMRBR Curator Damien Ihrig: damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154 to take a look at this book.

The Hardin Library bus stop (Stop 0254) will close on May 17, 2024, due to construction on Newton Road.

The VA Hospital stop (Stop 0253) is expected to close in late May or early June. Both stops will remain out of service during the project.

Use the Transit app for up-to-date information on routes and schedules.

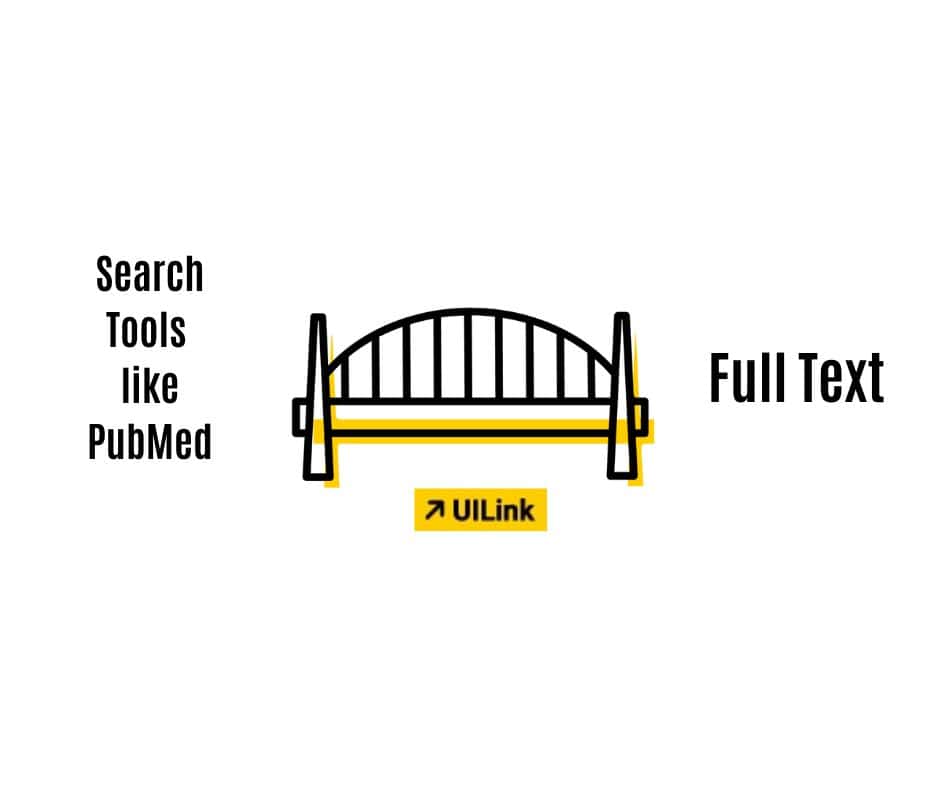

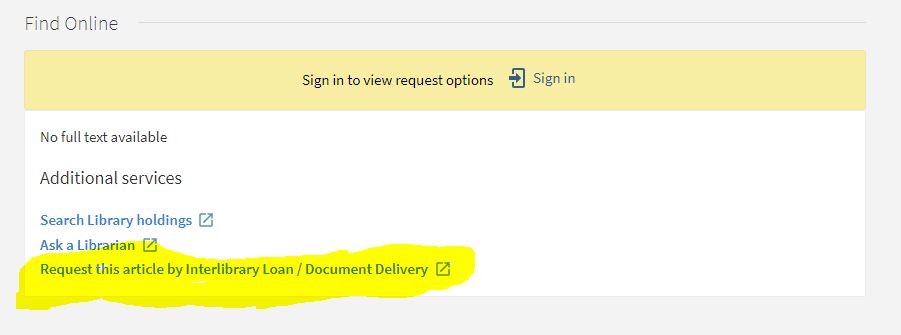

Full-text content from databases is often available using the UILink button. UILink is the tool that bridges our search tools like InfoHawk+, PubMed, and other databases to our subscriptions and full-text content. Make your experience seamless with the help of the best practices listed below.

1. Start at the Hardin Library website. Links leading from the website are coded to show you are affiliated with the University of Iowa and to display the UILink button.

2. Use your HawkID and password to access resources off-campus. Please note that this login information is separate from your UI Health Care credentials.

3. Click on “UILink” to see full-text options.

4. If we do not have the full-text, you can request the article through Interlibrary Loan.

5. If you have questions or difficulty accessing resources, please contact us.

We’re pleased to welcome Lisa Carrasco to the Hardin Library for the Health Sciences team as our new evening and weekend coordinator.

Lisa has 20-plus years of radio broadcasting experience and 18 years of teaching and library experience. She is from Mt. Pleasant, Iowa, and as a graduate of the University of Iowa is excited to be back on campus and part of Hardin Library.

Do you have book loans from the University of Iowa Libraries due in June 2024? It’s easy to return or renew (re-loan) those materials, especially to the Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, by Oct. 1, 2024. to avoid a replacement charge.

Renew your loans at the UI Libraires

Return books in person

Return books by mail

Additional return opportunities

Hardin Library also has a low-barrier book return at the Newton Road entrance. Come inside the first set of doors and you will see a wooden book return with a slot (nothing to pull) for returns. You may return any University of Iowa books here. This door is near a free parking spot and is handicapped-accessible.

If you need assistance returning your books due to a disability, please contact Michelle Dralle.

Please note: Materials due in June 2024 must be renewed or returned by Oct. 1, 2024, to avoid being billed a replacement charge.

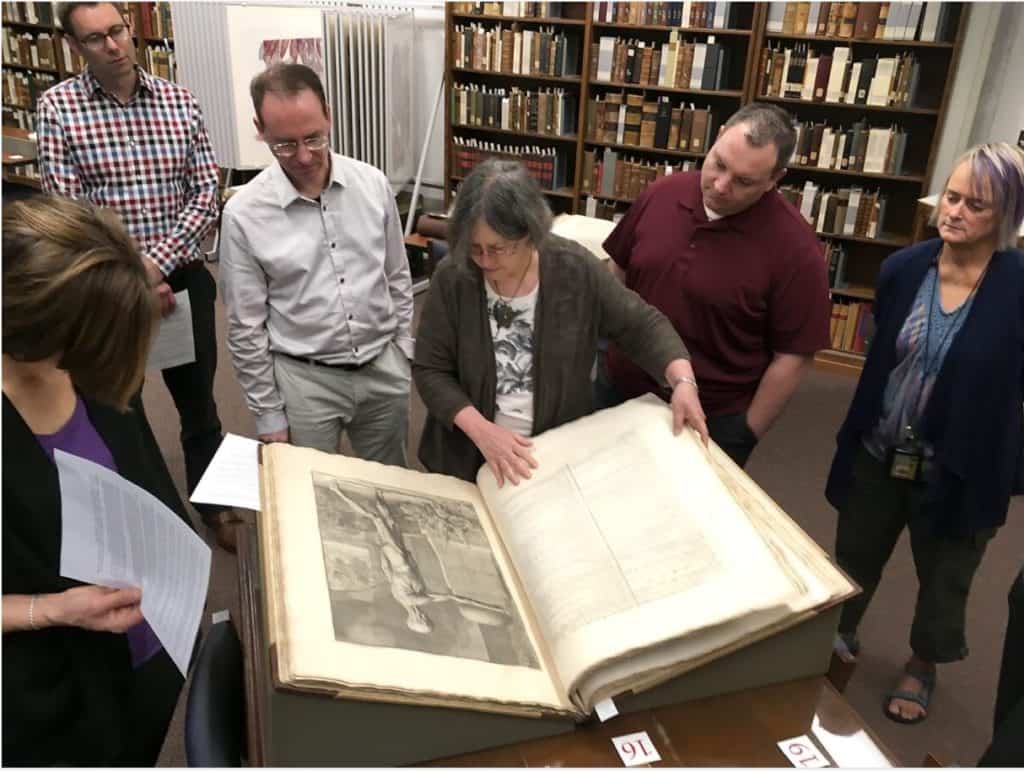

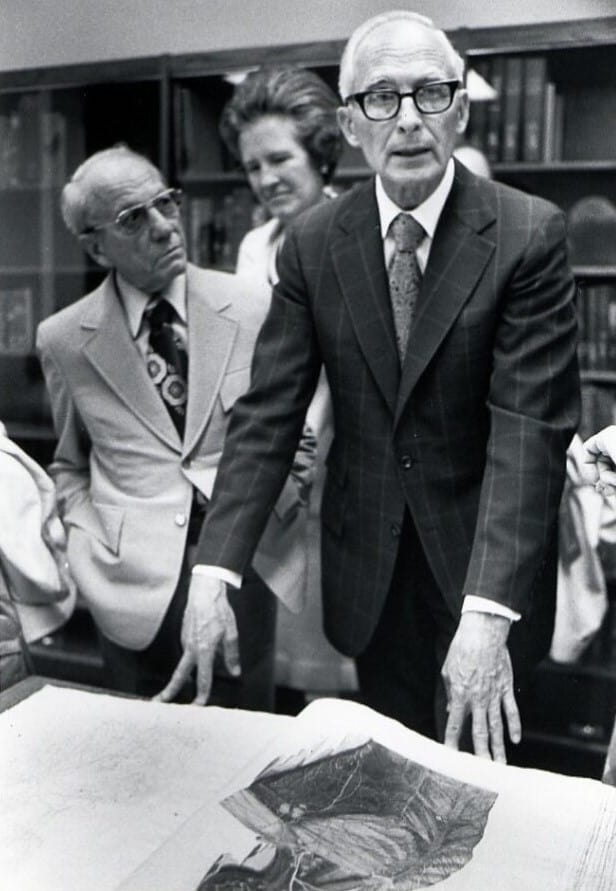

(Exhibit curated by Damien Ihrig, curator for the John Martin Rare Book Room, and Helen Spielbauer, creative coordinator, Hardin Library)

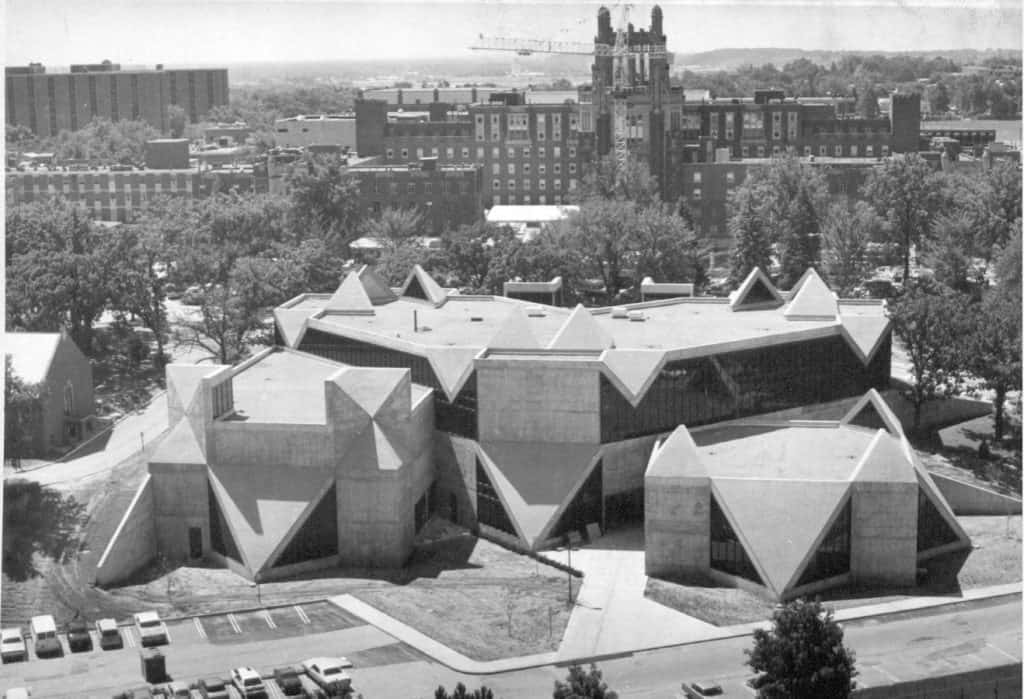

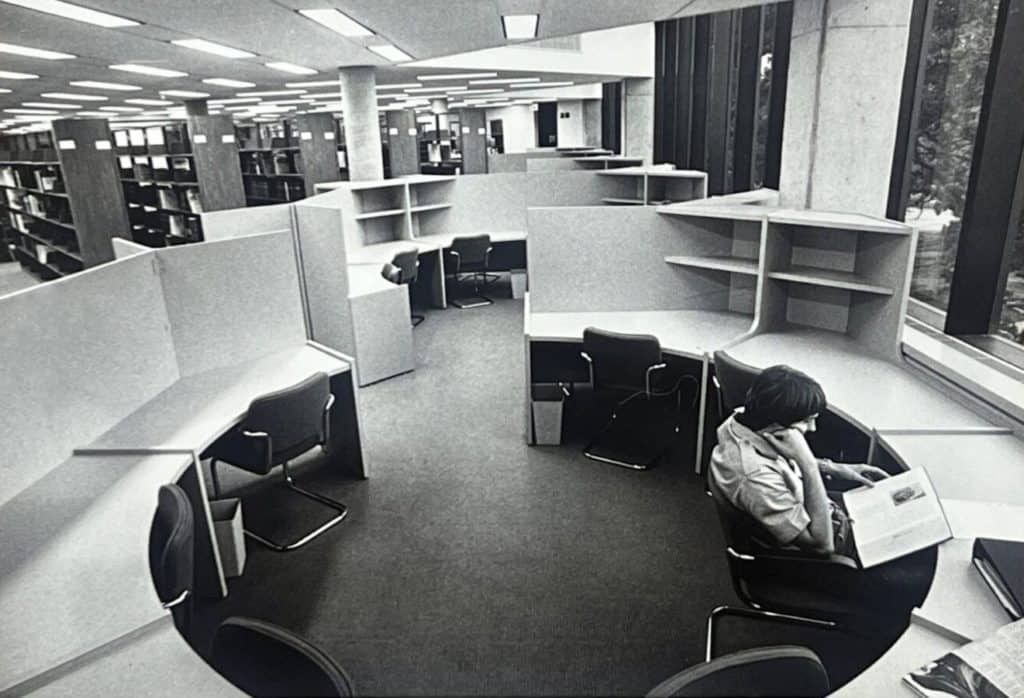

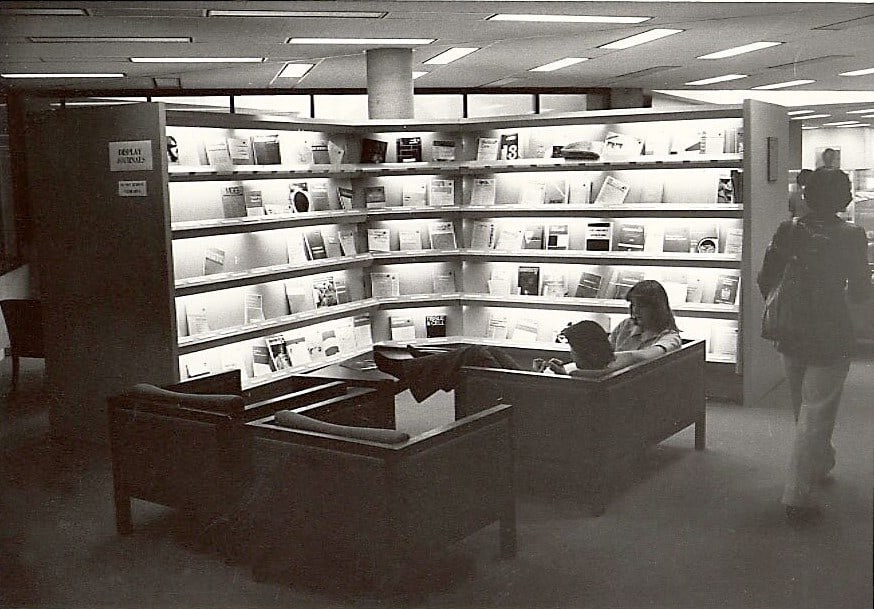

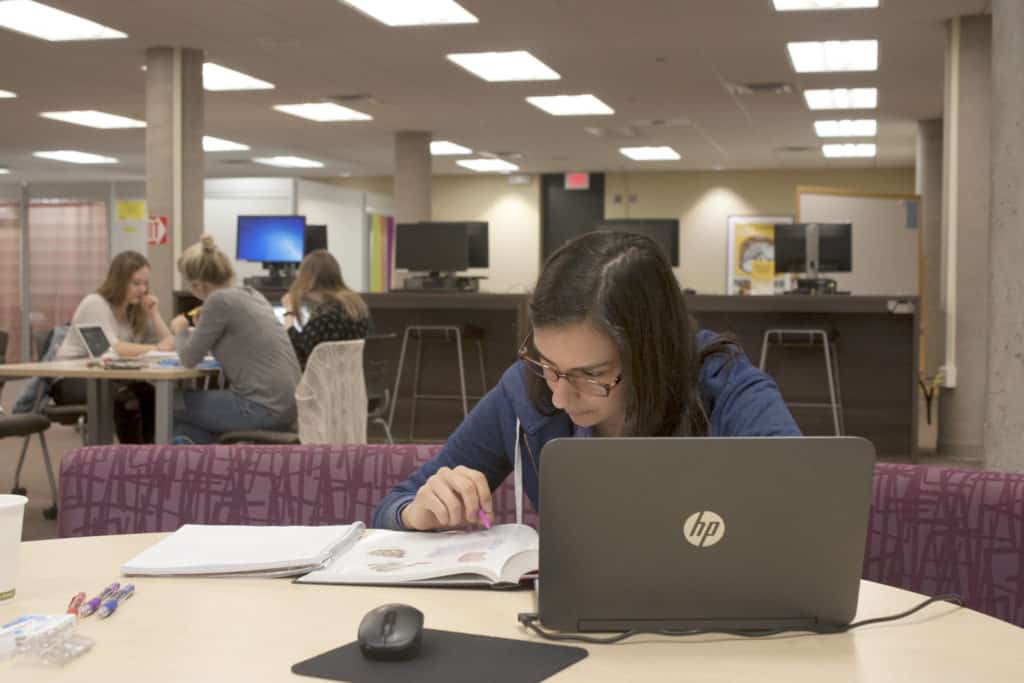

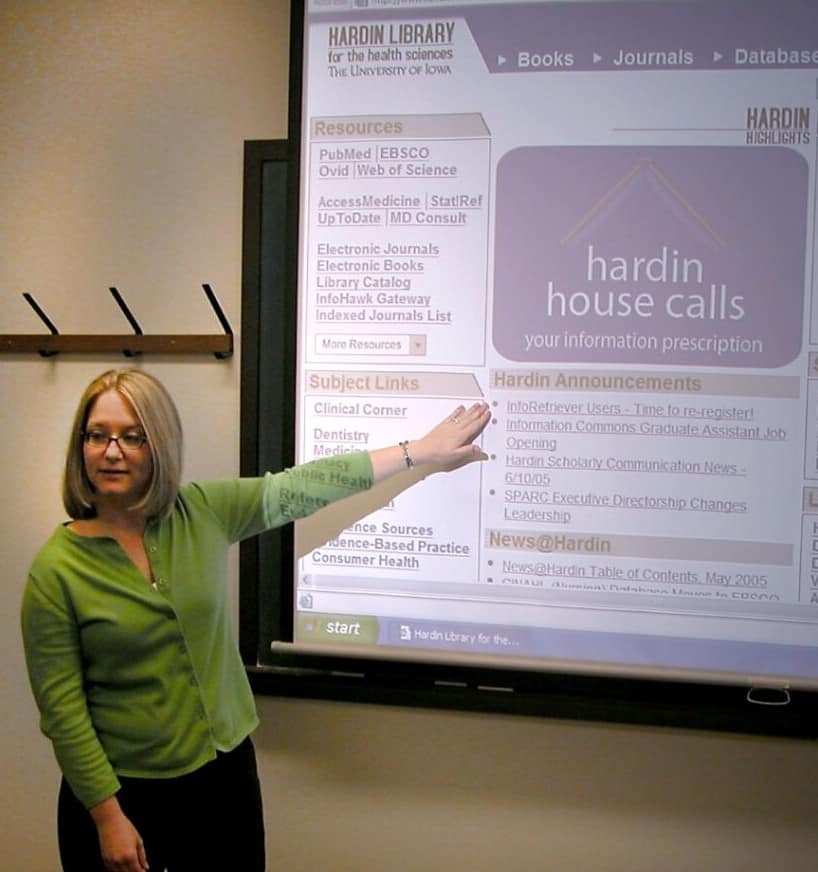

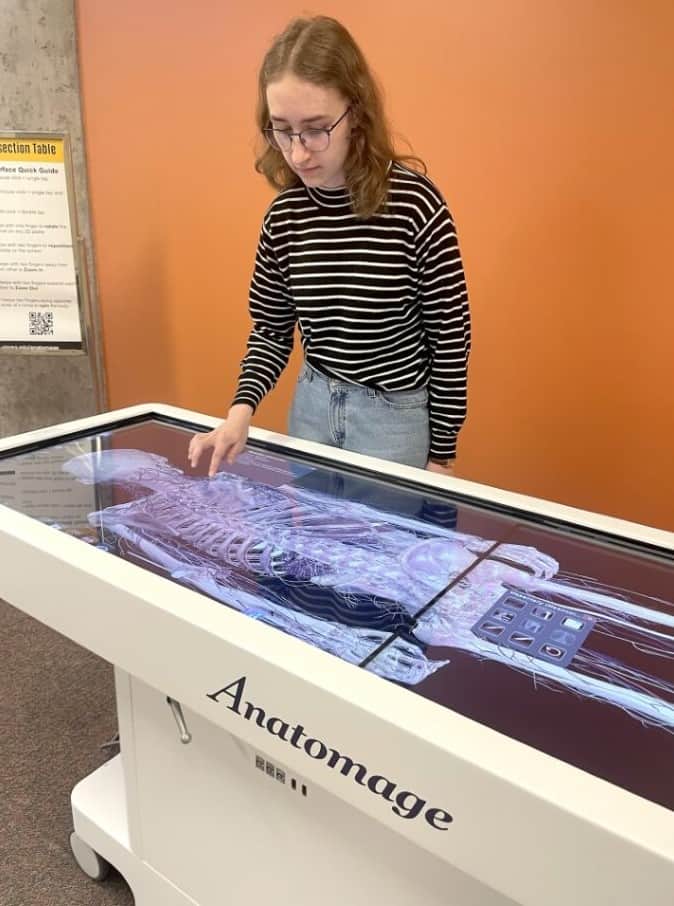

50 years ago this fall, the University of Iowa opened the Health Sciences Library, later named in 1988 after Dr. Robert C. Hardin. A former physician and professor of internal medicine, Dr. Hardin served as the dean of the College of Medicine and vice president of health affairs.

The state-of-the-art facility replaced the out-of-date and overcrowded medical library in the Medical Laboratories building and served all the health sciences colleges, as well as the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics.

The library was designed as a dedicated resource for the health and information needs of UI faculty, staff, and students. Beyond traditional offerings like physical collections, interlibrary loans, and copying services, it included a 24-hour study area, early mainframe searching, numerous study spaces, and the John Martin Rare Book Room.

Guided by the principles of delivering high-quality library services, access to cutting-edge information resources, and providing secure and comfortable study and social spaces, Hardin Library and its dedicated staff strive to meet users’ evolving needs. The commitment is evident in the ongoing updates and renovations, including 2024 enhancements to the fourth floor and the John Martin Rare Book Room.

Please join us in a look back at 50 years of the Hardin Library for the Health Sciences as we look forward to the next 50!

See the full poster exhibit on display at the Hardin Library.

The poster is also available in Iowa Research Online.

Hardin Library for the Health Sciences is 50 years old in 2024. Please enjoy an annual calendar designed by Helen Spielbauer.

The Hardin Library for the Health Sciences Interlibrary Loan Department will be closed from Saturday, Dec. 23, until Tuesday, Jan. 2.

You may place interlibrary loans during this time, but the requests will not be sent to other libraries until Jan. 2. Most other Big 10 Academic Alliance libraries are closed during this time as well.

No physical items or electronic articles will be processed Dec. 23 and Jan. 2.

Hardin Library for the Health Sciences winter interim hours begin on Saturday, Dec. 16.

The 24-hour study is available for affiliates whenever the library is closed.

Regular hours resume on Tuesday, Jan. 16.

Get ready for finals at the Hardin Library. We want you to succeed!

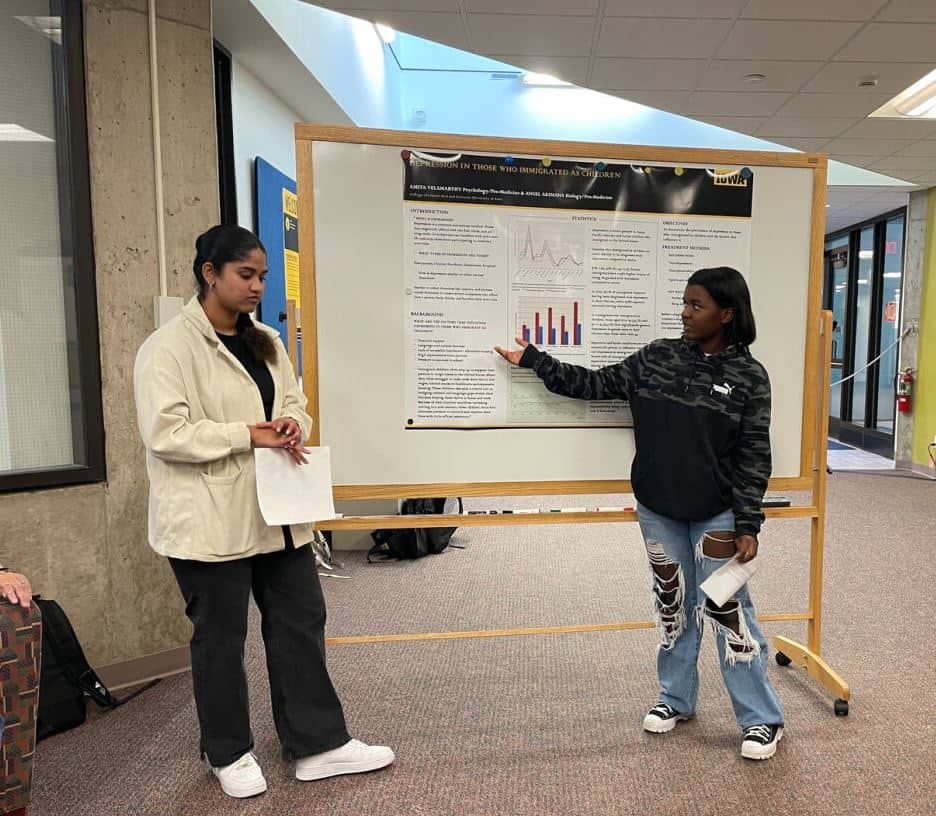

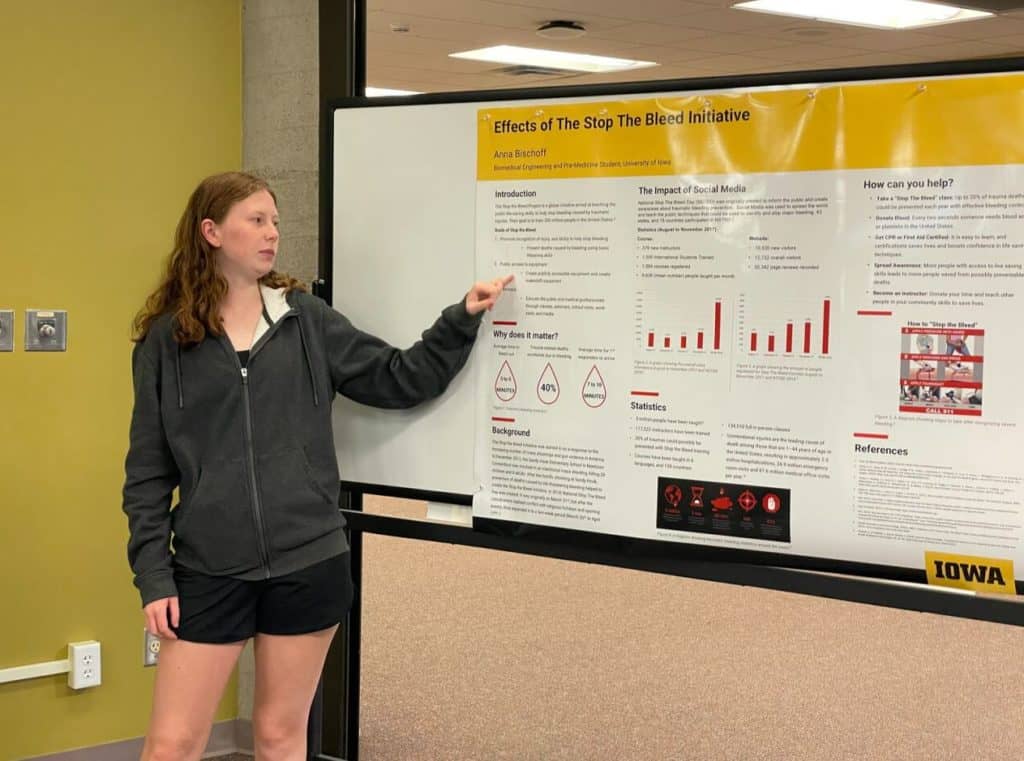

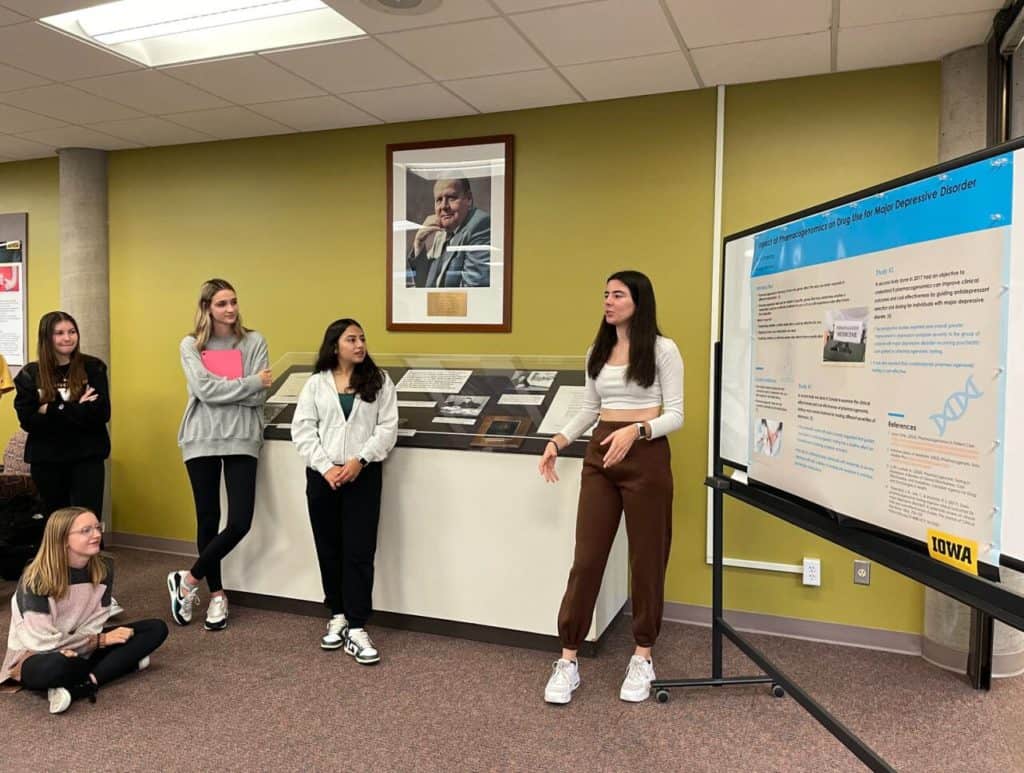

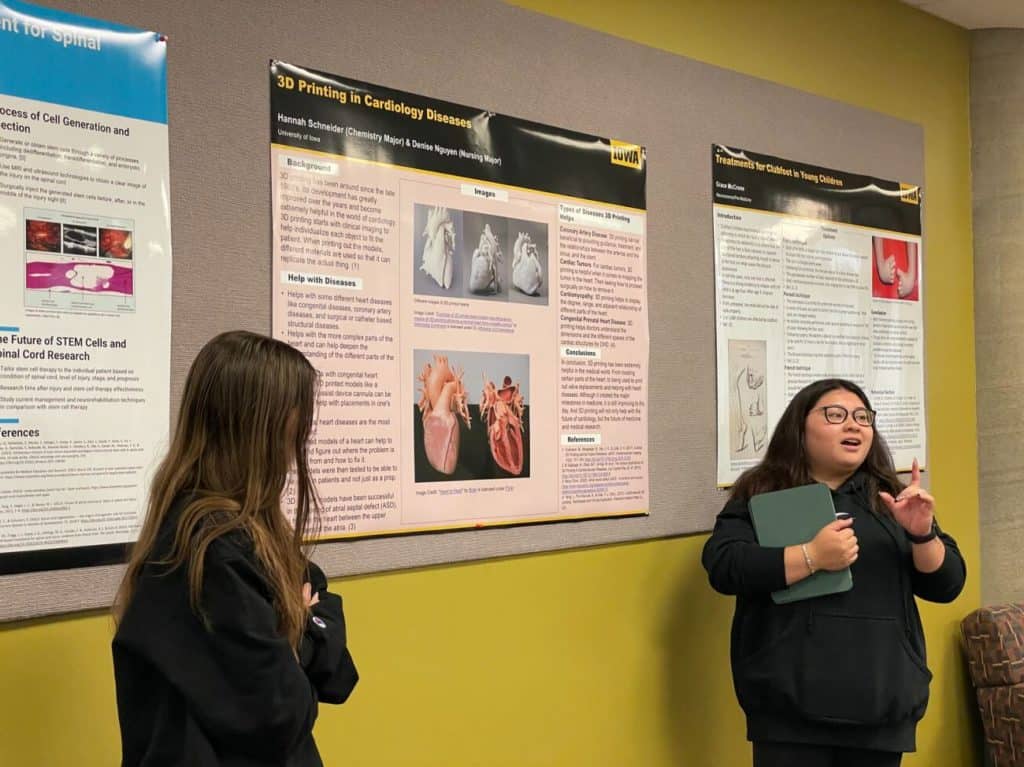

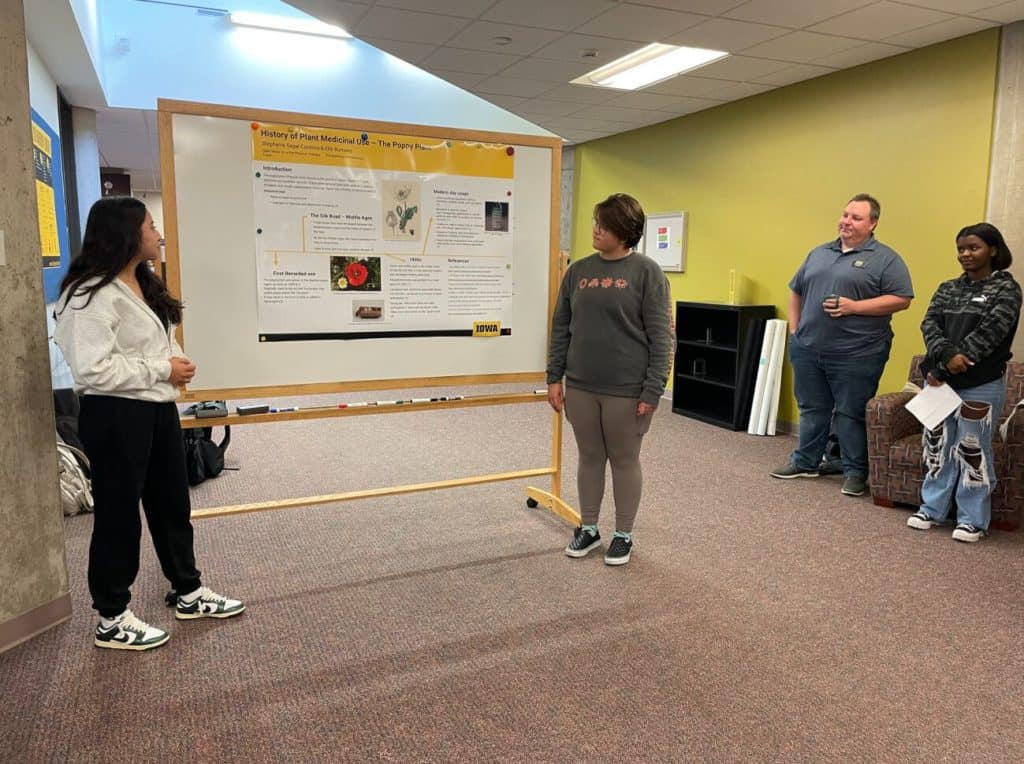

Hardin Library for the Health Sciences librarians Mary Thomas and Jennifer Deberg taught a first-year seminar this semester called “Exploring the Exciting World of Medical Research.”

The class was designed to stimulate students’ curiosity and encourage inquiry to answer their questions. Thomas and Deberg helped them learn to identify and differentiate the major types of health sciences research studies as well as how the scientific method and research life-cycle work. Students developed a research question, learned the process of designing a research project, and understood the dissemination process for research findings.

Here’s a look at the students’ final poster projects presented at the Hardin Library on Oct. 26, 2023.

All photographs by Helen Spielbauer. Used with permission.

by

Giselle Simón

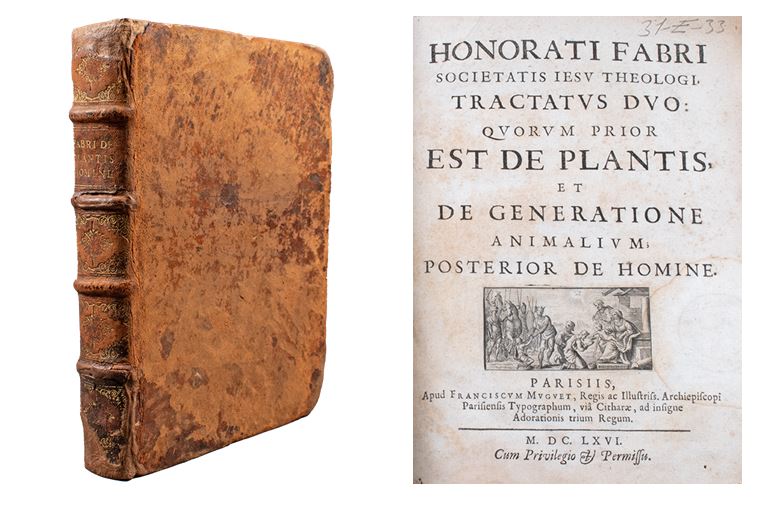

University Conservator

Director, UI Libraries Conservation and Collections Care

This particular treatment was a perfect candidate to test out some momigami, a long-fibered Japanese paper that is coated with konnyaku (a plant mucilage) and crumpled multiple times, giving it a fabric-like texture and strength. To back up a bit, early book repair and restoration treatments usually involved either a complete rebinding or what is known as rebacking: replacing the spine material (usually leather) with new leather and then repositioning the old leather spine piece that contains the titling, onto the newly rebacked spine. Leather work takes practice and skill, but more importantly, it is a naturally acidic material, and book conservators have been utilizing Asian-style papers, like Japanese kozo and Korean hanji for rebacking and mending of leather books since the 1980s.

There are still situations where leather is appropriate, and it’s a thoughtful conversation between curators and conservators, but the flexibility and accessibility of paper make it a great option. In some cases, like this treatment, it allows for more of the original spine to be saved by making small mends or fills rather than removing the entire spine.

This book’s leather covering is very abraded, although it is still structurally stable, giving it a sueded feel. The good thing is that the leather is in stable condition- it’s not suffering from too much desiccation or “red rot.” The spine is almost intact, with just a few areas of loss at the head and tail, a small missing patch over the raised bands, and some loss at the corners.

Using the momigami with its fabric-like nature, I was able to fill areas of loss that mimic the original leather, but the paper also flexes and moves over the joint and around the spine of the book, movement that is needed to open and close it again and again. The momigami provided a strong yet thin bridge between the thick pulp boards and their necessary connection to the spine area as if new ligaments were installed. The paper was also easy to shape when moist with adhesive and can be torn to produce a soft, feathered edge when applying in order to mesh with the original leather.

The paper can also be toned with stable paints, such as acrylics, to soften the interruption between old and new materials. In repairs like this, I try not to hide it completely, but I also want to find a balance for the reader so that it is not a distracting intervention.

Damien Ihrig, MA, MLIS

Curator, John Martin Rare Book Room

Over time, books can start to show their age. All kinds of things take their toll on a book – fire, pollution, pests, and acidic inks, to name a few. Mostly, though – and this makes me very happy – books just get used. And that use adds up.

Thankfully, we have a crack team of folks who specialize in making sure our books are preserved for as long as possible and continue to be available for our users. Our book this month represents one of the many items that make their way through the gentle and skilled hands of our Conservation and Collections Care staff.

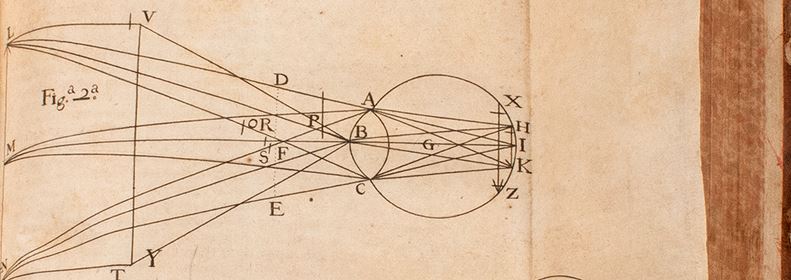

The French scientist and Jesuit priest Honoré Fabri (1608-1688) wrote his Tractatus duo: quorum prior est de plantis, et de generatione animalium; posterior de homine [Two treatises: the first of which is about plants and about the generation of animals; the latter of man] in 1666. It recently spent some time in Conservation for care.

As for Fabri, he was a prominent scientific figure during the 17th century. Jesuit priest was his day job, but he showed an early aptitude and genuine passion for math and science. That passion would eventually get him in trouble with both the Catholic Church and the scientific community, including a short stint in prison and an argument with the famous Dutch polymath Christiaan Huygens that clocked in at five years!

FABRI, HONORÉ (1608-1688). Tractatus duo: quorum prior est de plantis, et de generatione animalium; posterior de homine [Two treatises: the first of which is about plants and about the generation of animals; the latter of man]. Printed in Paris by François Muguet, 1666. 25 cm tall.

Fabri was born April 8, 1608, in Le Grand Abergement. His education started at the Catholic Institute in Belley, where he developed a strong interest in math and science and exhibited a quick wit. He entered the Jesuit Order on October 18, 1626, spending time in Avignon and Lyon for his studies.

Fabri showed a knack for teaching during his tenure as a professor of philosophy in Arles from 1636 to 1638, where he covered subjects like logic, philosophy, and natural philosophy. Fabri’s enthusiasm for teaching and exploring various disciplines led him to hold positions in several Jesuit colleges. He taught logic and mathematics in Aix-en-Provence and later returned to Lyon, where he had a remarkable and productive period as a professor. During this time, he covered a wide range of subjects such as logic, mathematics, natural philosophy, metaphysics, and astronomy. Many of his works were derived from his lectures during this phase.

While Fabri’s teachings were respected, his writings did not sit well within the Jesuit Order for reasons that are not entirely clear. What is clear is that Fabri investigated scientific and philosophical “novelties,” which seem to have irked his conservative colleagues. This led to his removal from teaching in 1646 and a series of reassignments.

He was eventually accused of adhering to the religious and scientific philosophy of Descartes (banned by the church in 1663) and imprisoned.

Fabri also engaged in significant scientific debates during his lifetime. His dispute with Christiaan Huygens about Saturn’s rings is especially notable. Initially, Fabri proposed an alternative theory to Huygens’ ring concept, but after a brief five years of debate, he conceded and adopted Huygens’ theory. Fabri also contributed to astronomy by discovering the Andromeda nebula and working on the theory of tides influenced by lunar action.

In the realm of mathematics, Fabri’s work on calculus is noteworthy. He collaborated with Michelangelo Ricci (the “other Michelangelo”) and significantly impacted the development of calculus, particularly influencing Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. In fact, Leibniz placed Fabri with Galileo, Torricelli, Steno, and Borelli for his work on elasticity, vibrations, and the study of motion.

Not content with making his mark solely in mathematics, physics, and astronomy, Fabri made waves in medicine, too, although not without controversy, of course. Some tried to foster a blood feud between Fabri and William Harvey, claiming that Fabri’s lectures indicate he discovered the circulation of blood prior to Harvey. Thankfully, Fabri staunched the flow of discord by stating definitively that “at no time did I ever say that the circulation of the blood had been first discovered by me.”

Contact curator Damien Ihrig to take a look at this book: damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154.

Color and black and white printing are available at the Hardin Library. Students and all University of Iowa affiliates can make printouts and the charges go on your U-Bill.

Black and white printing 3 cents per side

Color printing 15 cents per side

You can send print jobs from home to Hardin Library for pick up.

1. Log into the PaperCut system with your Iowa HawkID and password.

2. Select web print.

3. Upload your documents. All printing will be double-sided using this system.

4. Come to the library within a few hours, log into the print release stations in 24-hour study, 3rd floor, of Information Commons West, or 2nd floor and release the jobs to pick up your printouts.

*We do not recommend releasing your job until you come to the library to keep your materials private and secure.*

We are currently working on course reserves for Fall 2023. If you have materials you would like to place on course reserve, please submit an online “Hardin Library – Place Items on Reserve” form at http://www.lib.uiowa.edu/hardin/hardin_reserve.

You can also e-mail Mark Onken directly at mark-onken@uiowa.edu. Please list your course number and the specific materials you would like us to place on reserve for your course.

Heather Healy, MA, MLS, AHIP was appointed a distinguished member of the Academy of Health Information Professionals (AHIP) in May.

The Academy of Health Information Professionals is a professional development and career recognition program of the Medical Library Association (MLA). The AHIP portfolio-based certification indicates that Healy’s peers in the field of health sciences librarianship have certified that she has met a standard of professional education, experience, and accomplishment and demonstrated that she is committed to career development. AHIP Distinguished, the highest of four levels, requires a minimum of 10 years of full-time professional work experience as well as a significant number of professional accomplishments over the prior five years.

Healy has served since March as Chair of MLA’s Systematic Review Services Specialization Workgroup—which develops and maintains the Systematic Review Services Specialization—and in June received an official one-year appointment as Chair. Healy also serves on the Executive Board of the Midwest Chapter of the Medical Library Association as the chapter’s Representative to the MLA Chapter Council.