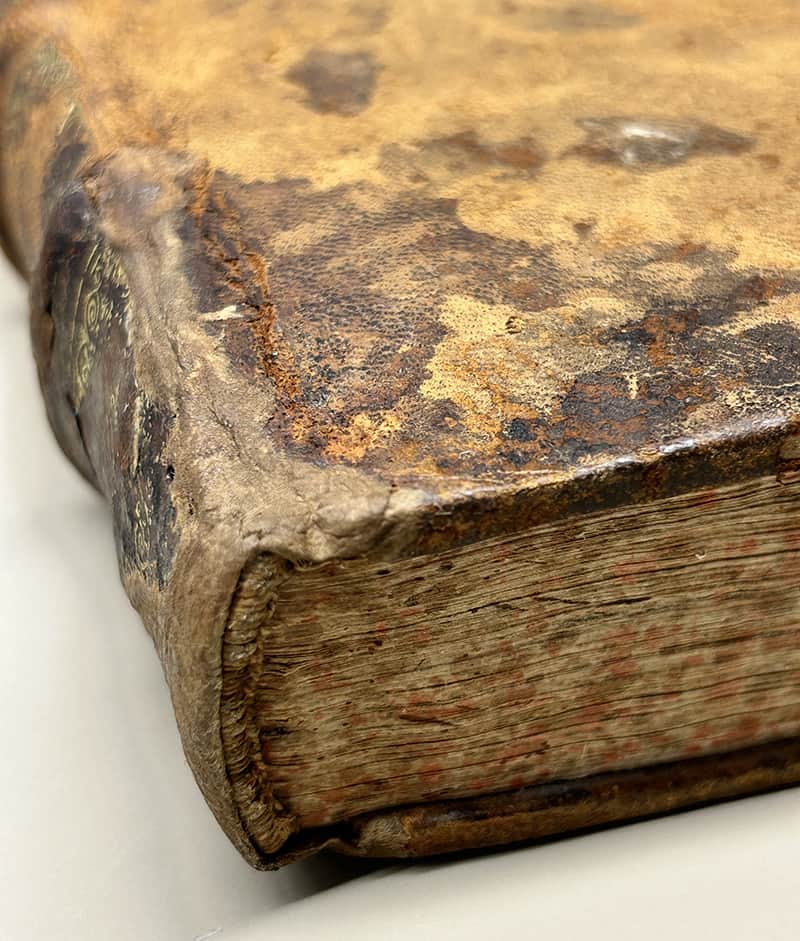

by Giselle SimónUniversity ConservatorDirector, UI Libraries Conservation and Collections Care This particular treatment was a perfect candidate to test out some momigami, a long-fibered Japanese paper that is coated with konnyaku (a plant mucilage) and crumpled multiple times, giving it a fabric-like texture and strength. To back up a bit, early book repair and restorationContinue reading “The Fabri-c of Our (Book) Lives | Conservation Corner”

Tag Archives: rare books

Absolutely Fab-rius | Notes from the John Martin Rare Book Room @Hardin Library

Damien Ihrig, MA, MLISCurator, John Martin Rare Book Room Over time, books can start to show their age. All kinds of things take their toll on a book – fire, pollution, pests, and acidic inks, to name a few. Mostly, though – and this makes me very happy – books just get used. And thatContinue reading “Absolutely Fab-rius | Notes from the John Martin Rare Book Room @Hardin Library”

Damien Ihrig | Curator | Waste Not, Want Not: Exploring the Binder’s Waste of the John Martin Rare Book Room | Video available

Damien Ihrig is the Curator for the John Martin Rare Book Room (JMRBR) in the Hardin Library for the Health Sciences at the University of Iowa. He works with researchers of all ages and from various backgrounds to find and use information on the history of the health sciences. He also manages the collection of rareContinue reading “Damien Ihrig | Curator | Waste Not, Want Not: Exploring the Binder’s Waste of the John Martin Rare Book Room | Video available”

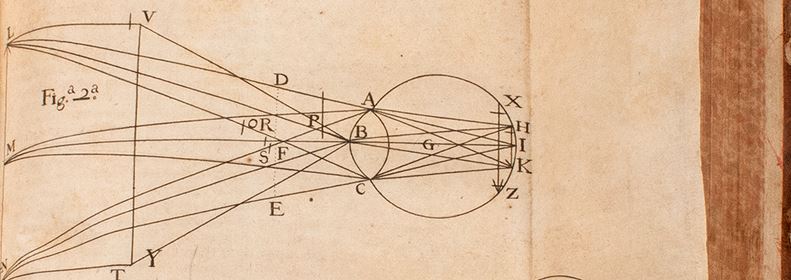

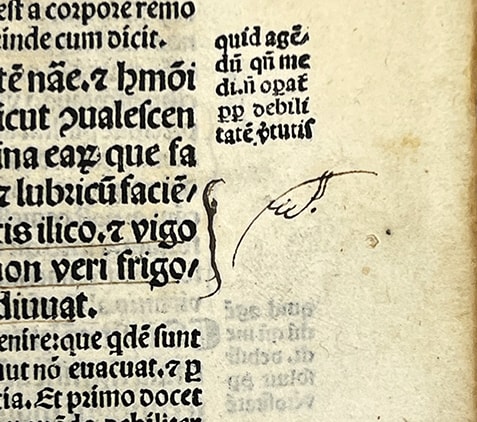

Popular Pharmacy Handbook of Medieval Europe | November Book of the Month from the John Martin Rare Book Room @Hardin Library

by Damien Ihrig, Curator, John Martin Rare Book Room @Hardin Library MESUË THE YOUNGER (fl. ca. 1200?). Canones universales. First Giunta edition. Printed in Venice by Luca-Antonio Giunta, 1527. 388 leaves. 32 cm tall. Mesue’s works were an immediate hit. Some of the most famous western physicians of the time, including Petrus de Abano and Mondino dei Luzzi, wrote commentaries on Mesue’s work. Canones,Continue reading “Popular Pharmacy Handbook of Medieval Europe | November Book of the Month from the John Martin Rare Book Room @Hardin Library”

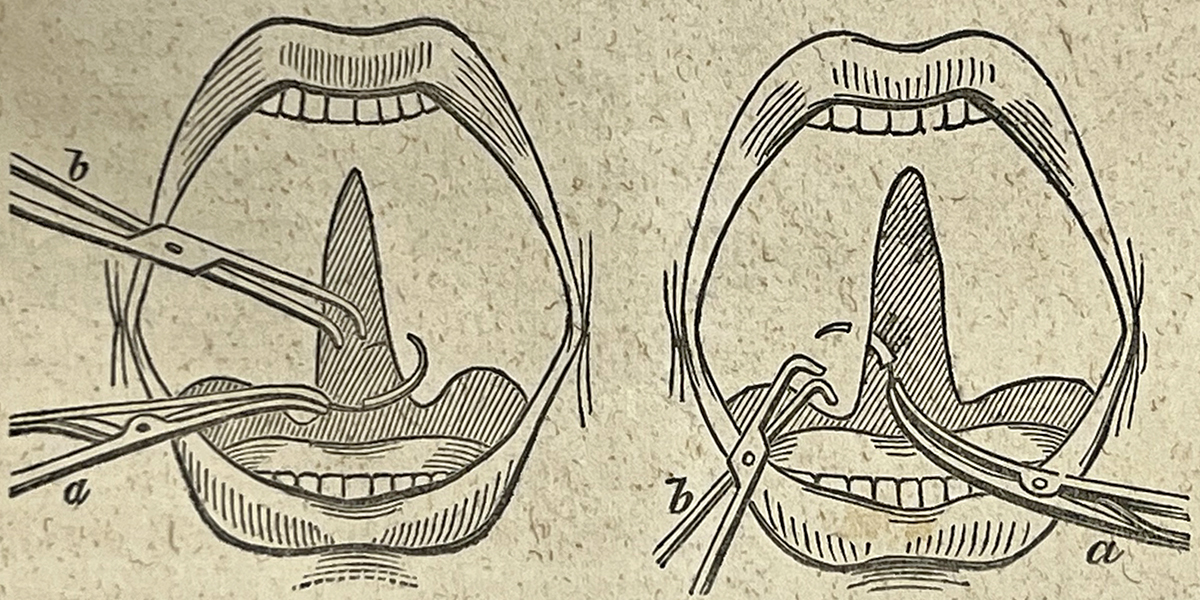

1843 American Cleft Palate Surgery Book | Thomas Dent Mütter | from The John Martin Rare Book Room @Hardin Library

by Damien Ihrig, MA, Curator John Martin Rare Book Room MÜTTER, Thomas Dent (1811–1859). A report on the operations for fissures of the palatine vault. Printed in Philadelphia by Merrihew & Thompson, 1843. 28 pages. 23 cm tall. The Mütter Museum in Philadelphia is celebrated for its collection of anatomical specimens of rare conditions, from the famous (and infamous), asContinue reading “1843 American Cleft Palate Surgery Book | Thomas Dent Mütter | from The John Martin Rare Book Room @Hardin Library”

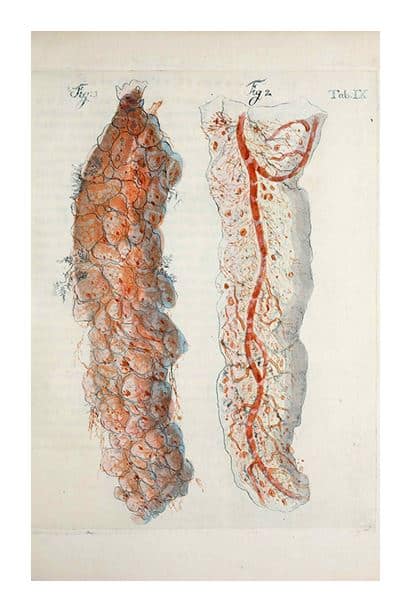

New Acquisition | John Martin Rare Book Room | Bleuland, Otium academicum

BLEULAND, JAN (1756-1838) Otium academicum : continens descriptionem speciminum nonnullarum partium corporis humani et animalium subtilioris anatomiae ope in physiologicum usum praeparatarum, aliarumque, quibus morborum organicorum natura illustratur. [Academic leisure: containing a description of several specimens of the human body and of exact animal anatomy prepared for use in physiology, and containing a description of otherContinue reading “New Acquisition | John Martin Rare Book Room | Bleuland, Otium academicum”

New Book: Theodor Schwann, Mikroskopische…, 1839 | John Martin Rare Book Room @Hardin Library

THEODOR SCHWANN (1810-1882). Mikroskopische Untersuchungen über die Uebereinstimmung in der Struktur und dem Wachsthum der Thiere und Pflanzen. [Microscopical researches into the accordance in the structure and growth of animals and plants] Printed by Georg Reimer in Berlin in 1839. First edition. 270 pages. 21 cm tall. Schwann was an energetic and talented researcher, inventor,Continue reading “New Book: Theodor Schwann, Mikroskopische…, 1839 | John Martin Rare Book Room @Hardin Library”

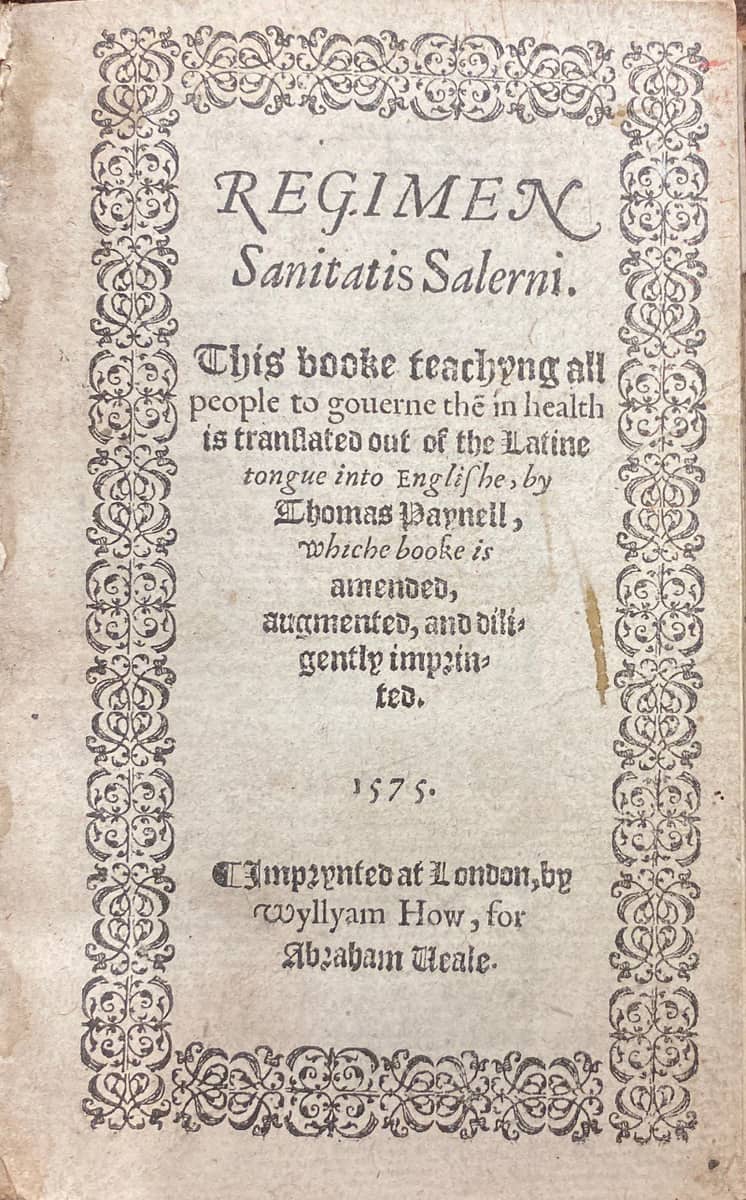

Medieval Home Medicine | Week 3 | National Poetry Month @Hardin Library

Celebrate National Poetry Month by viewing this medieval didactic poem in hexameter verse. Make an appointment to view in person or by Zoom with curator damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or by calling 319-335-9154. REGIMEN SANITATIS SALERNITANUM The Englishmans doctor, or, The school of Salerne. Printed for John Helme 1612 5th impression. [48] pp. 13.7 cm. First English translationContinue reading “Medieval Home Medicine | Week 3 | National Poetry Month @Hardin Library”

You cannot judge a book by its cover. The title page is another story.

by Duncan Stewart, MA, MLIS, Rare Materials Cataloger, University of Iowa Libraries, Adjunct Faculty, School of Library and Information Sciences, University of Iowa The John Martin Rare Book Room (JMRBR) is filled with books of great medical historical value. But do you know how all those books get into the JMRBR? A book’s journey toContinue reading “You cannot judge a book by its cover. The title page is another story.”

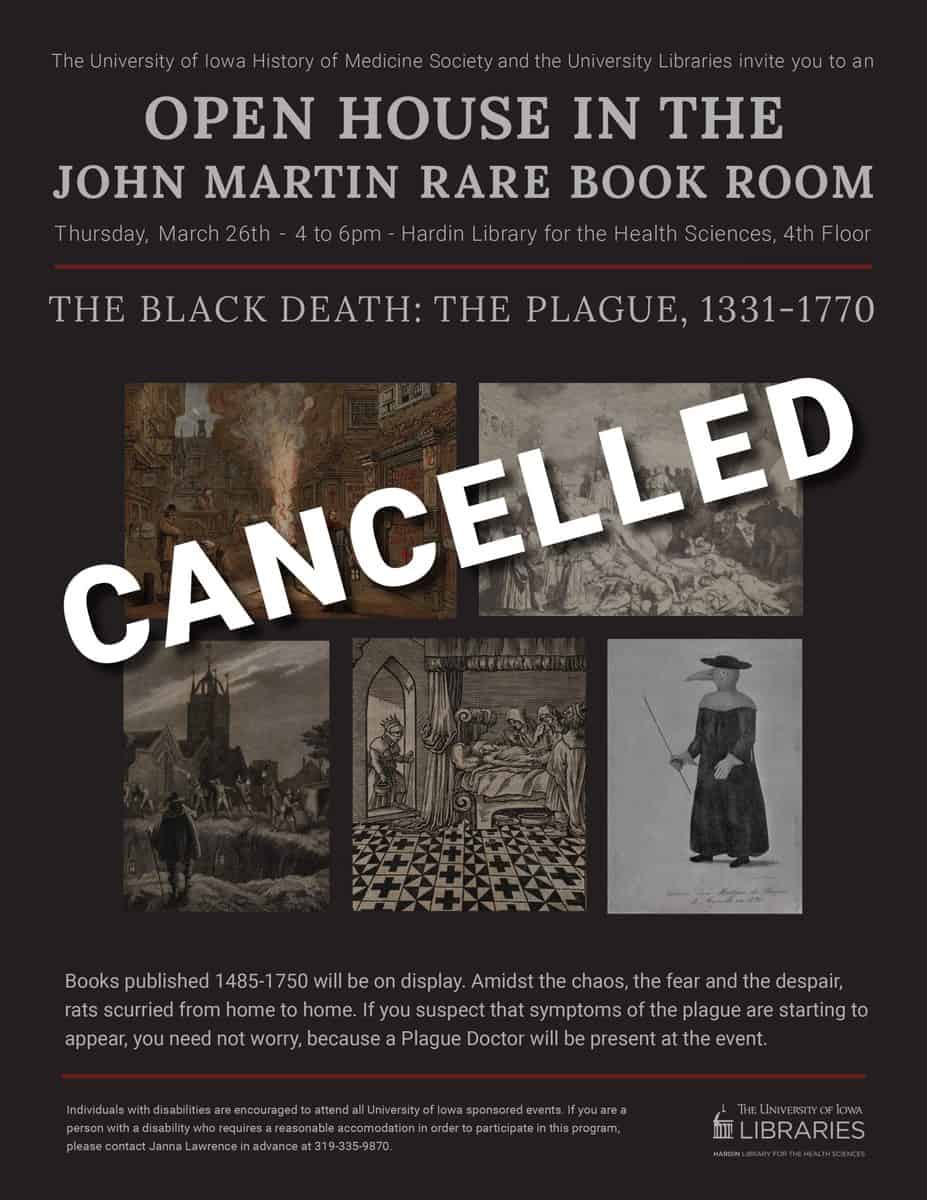

CANCELLED |2020 Open House | John Martin Rare Book Room @Hardin Library | Black Plague | March 26

The 2020 John Martin Rare Book Room Open House has been cancelled. This event will not be rescheduled. Please see our online exhibit: The Black Death: The Plague, 1331-1770