MARTINEAU, HARRIETT (1802-1876). Life in the sick-room: Essays. Printed in Boston by L.C. Bowles and W. Crosby, 1844. 20 cm tall.

Martineau was born in 1802 into a progressive Unitarian family in Norwich. Despite the societal expectations that confined her to domestic roles, Harriet’s intellect and determination were undeniable. In 1823, she challenged gender norms by anonymously publishing On female education, advocating for women’s rights to education and intellectual pursuits.

Her literary breakthrough came with the publication of Illustrations of political economy in 1832, a series of short stories that deftly wove economic theories into narratives about everyday people. This work not only brought her fame and financial security but also highlighted her as a significant intellectual force.

From 1834 to 1836, Martineau traveled across the United States. A staunch abolitionist and advocate for women’s rights, she wrote extensively against slavery and the lack of opportunities for women, eventually writing Society in America. Her extensive travels also led to insightful writings on the Middle East, India, and Ireland, further establishing her as a versatile and influential journalist and author.

Martineau began experiencing a series of symptoms while on her travels and, in 1839, returned to England for treatment. For someone experiencing a debilitating illness but not necessarily dying, being confined to a “sick room” was common at this time. It allowed the room to be set to the orders of the physician and made it easier for the family to care for their ill relative.

Although confined to her own sick room for five years, Martineau was financially secure and had a progressive, independent spirit. She oversaw her medical care and constructed an environment that best suited her needs. She even restricted access from her family, who she felt could be more emotionally draining than helpful. While resting and recuperating, Martineau remained very productive, writing a novel for children and the essays eventually published in Life in the sick-room.

Already considered an irritation in the medical community, she really caused a stir by claiming that Mesmerism, a pseudo-science medical treatment, cured her. Franz Anton Mesmer (1734-1815), a German physician, maintained that an “animal magnetism” pervades the universe and exists in every living thing.

He believed that its transmission from one person to another could cure various nervous disorders through its healing properties. Mesmer at first used magnets, electrodes, and other devices to effect his cures, but after arousing suspicion among his fellow physicians, he preferred to utilize his hands.

Considered quackery by many in the medical establishment, even in 1844—including by her physician brother-in-law who oversaw her care—physicians publicly attacked Martineau’s claims about Mesmerism. Her brother-in-law eventually published a detailed account of her illness. Although he promised it would anonymously appear in a medical journal, he instead created a public pamphlet and made little effort to disguise who he was talking about.

After ten years of good health, Martineau once again fell ill in 1855 and returned to her sick room. She remained there until her death in 1876. She continued to write during this time, completing, among other things, her autobiography, works promoting women’s suffrage, and critiques of the Contagious Diseases Acts, which targeted women in the name of preventing sexually transmitted illnesses.

After her death, the medical establishment, again including her brother-in-law, who publicly published the results of an unauthorized autopsy, went out of their way to discredit Martineau and her work. Without evidence, they claimed her illness led her to behave in unconventional and “unfeminine” ways. Martineau remained an inspiration to many, though, and her works live on as a testament to her resilience and rejection of the status quo.

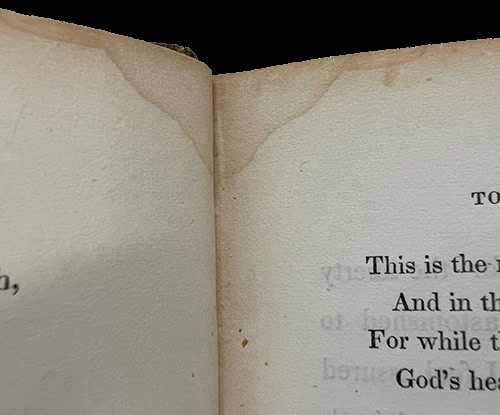

Our copy of the first American edition of Life in the sick-room is quite unassuming. It features a standard 19th-century burgundy cloth cover that has faded over time. Since it was a book in the library’s circulating collection for most of its life, it features a “library cloth” rebacked spine with the label maker-printed call number and title easily visible. Inside, the paper is in good condition, with evidence of damage from a long-ago liquid spill. Much like Martineau herself, though, this little book has shown great resilience in the face of adversity!

Contact the JMRBR Curator Damien Ihrig: damien-ihrig@uiowa.edu or 319-335-9154 to take a look at this book.